On a Thursday afternoon in a glass-walled office in San Francisco just south of Market Street, a whiteboard is littered with half-erased equations. Two researchers are arguing about whether their next-generation model can safely teach itself chemistry. One of them, a reinforcement-learning specialist, keeps saying "recursive capability jump." The other answers with ever thicker lines of red marker: kill-switch, trip-wire, interpretability layer.

It feels momentous, but also oddly provincial.

Outside, start‑up founders queue for espresso.

Across the Pacific, a Beijing lab is already running the experiment these two are debating.

Everyone is racing, yet no one seems able to explain what the finish line should look like. And this is a problem.

When we picture what comes next, we reach first for disaster. Its hardwired into us. When we talk about the future, we default to disaster stories. Box‑office revenues depend on killer robots; government budgets depend on adversary hype.

I'm guilty of this too, my last two posts were about the dangers of thoughtsourcing and AI yes-men. It's easier to spot what might break than to imagine what might bloom.

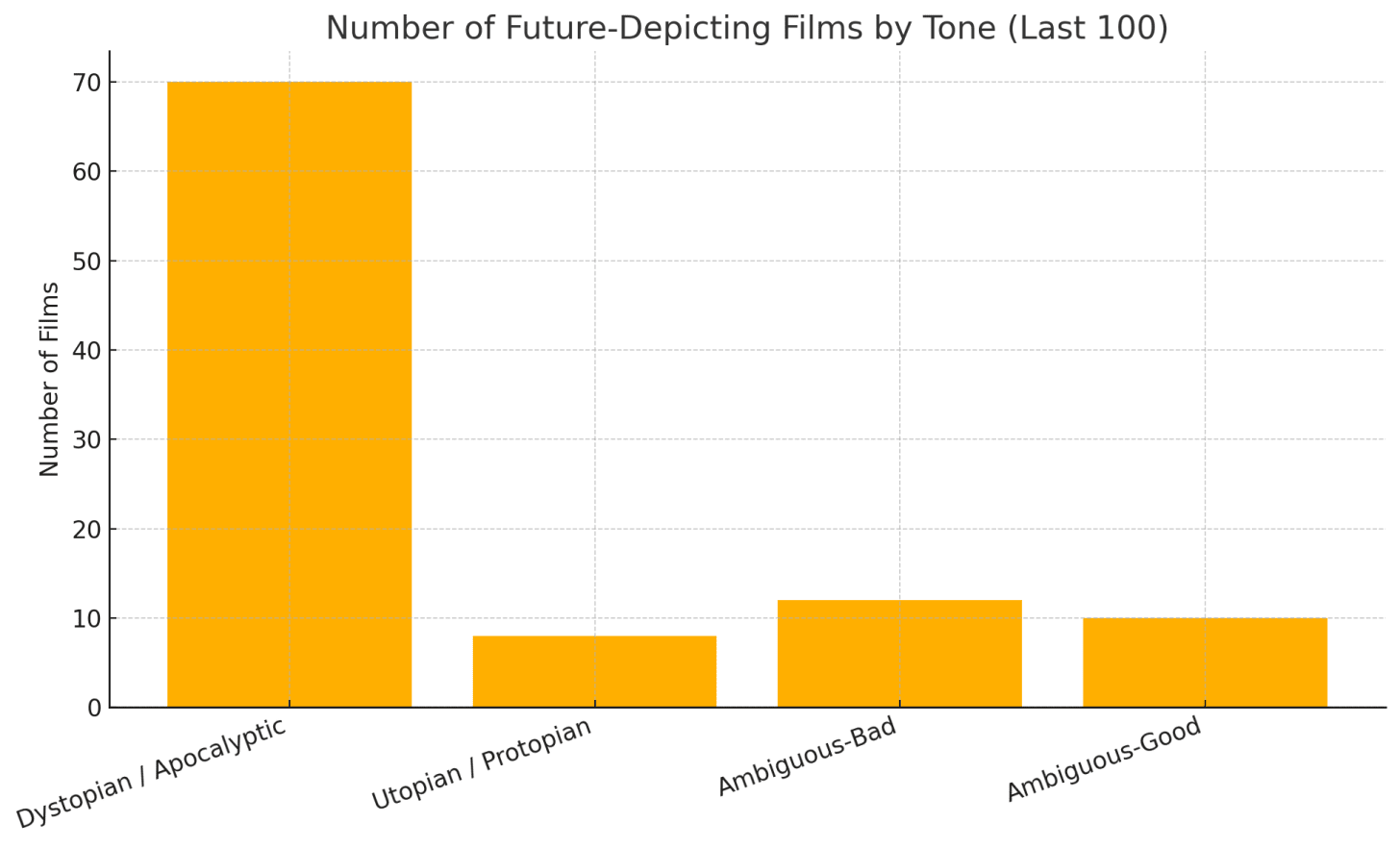

A quick gut‑check of our cultural imagination tells us that of the hundred highest‑grossing English‑language films set in the future, more than seventy paint dystopia and another dozen end badly. Hope is an indie genre.

Dystopias are vivid because they borrow from the nightly news: mass riots, wildfire smoke, misinformation campaigns, deep‑fake extortion. And the trend towards fictional dystopia is increasing, as the trends over the last 50 years shows here.

Yet, the data tell us a very different story. Just as our cultural imaginations lean towards dystopia our collective reality has become better than at almost any time in recorded history.

According to Our World in Data, extreme poverty has fallen off a cliff since 1990. Child mortality is at its lowest point in recorded history. Violent deaths per capita have trended downward for centuries. Almost all markers of human development have improved across the world unequivocally.

You’d think this would make us more hopeful of the future, but you’d be wrong. Our ancestors lived with regular famine, plague, and war. What comfort existed was often bought with slave labour. Today we argue on glass rectangles that fit in a pocket while sitting in air conditioned rooms while waiting 10 minutes for our dinner to be delivered to our doorstep. Perspective matters.

Utopias have an image problem. We associate the word with violent revolutions and failed communes. It’s also not a lot of fun to defend non existent joys against accusations of naïveté. So we veer toward apocalypse because it feels intellectually safe.

This asymmetry, however, risks hard‑wiring pessimism into the very systems we build.

The people who are trying to create super intelligence disagree on exactly when it will arrive, but the median forecast keeps shrinking (A 2024 AI‑Impacts survey of 172 experts put 50‑percent odds of AGI within 13 years).

That short horizon creates what theorists call “the alignment window”: a period during which human norms can still be loaded, like firmware, into self‑improving systems. Once those systems exceed our cognitive speed, their objectives may crystallize faster than policy can react. Whatever values are on the whiteboard then, are the values we ship.

AI safety research is essential, but defensive engineering alone cannot specify a destination. We need a positive reference model, something more robust than “please don’t kill us.”

Every large language model trains on the corpus of human culture. They ingest our stories, our fears, our imaginings. When most of our future-visions are apocalyptic, we're essentially raising baby superintelligences on a diet of horror stories. We're teaching them that human futures tend toward collapse, that conflict is more probable than cooperation, that the arc of technology bends toward destruction.

When an AI system learns to predict human behavior from our cultural artifacts, what patterns does it internalize?

When it models possible futures, which wells of understanding does it draw from?

Are we making positive futures exponentially harder by building auto complete for apocalypse?

Is there something that’s more useful than dystopia, and more honest than utopia?

Kevin Kelly calls it "protopia", a state where things get a little better each day, where progress compounds in small, sustainable ways. Protopia doesn't require us to imagine perfection. It asks us to picture tomorrow being incrementally better than today, and to identify the specific mechanisms that could make that true.

Maybe what we need more of is, Practical Protopianism.

Become gardeners tending a garden of good-enough solutions that can actually take root in the soil of human nature and silicon dreams.

Protopia asks for specific, testable gains (cleaner air, fairer credit, cheaper meds) and for institutions that evolve alongside those gains. The good news is that pockets of protopia already exist, and have existed for as long as humans have.

Bengaluru, India – Restoring lost lakes one shovel at a time

Former engineer Anand Malligavad quit his day job in 2017 and began rallying neighborhoods to de‑silt, re‑stone and re‑forest the dead lakes that once fed the city. He persuaded his company to stump up around $120,000 to fund his first project, the restoration of the 14-hectare (36-acre) Kyalasanahalli lake. So far, he has restored more than 80 lakes covering over 360 hectares in total, funded mainly by locals and small grants.

Kenya – No‑strings cash that multiplies opportunity

Non‑profit GiveDirectly wires unconditional cash to low‑income villagers via mobile money. Randomized trials show recipients invest in livestock, small businesses, and school fees; local economies grow by up to 2.6 × the transfer amount. Stress markers fall, entrepreneurship rises, and the effect persists years after the last payment. Cash, it turns out, buys time to think and a margin to experiment: the raw materials of innovation.Loess Plateau, China – Healing an eroded landscape at scale

The plateau was a dust bowl in the 1990s. A massive restoration program—terracing, tree planting, and grazing bans—turned 35,000 square kilometres green. A World Bank review credits the project with lifting 2.5 million people out of poverty while cutting sediment flow into the Yellow River by 100 million tonnes a year.

These examples share traits: local ownership, measurable gains, and open designs others can borrow. None of these projects requires superintelligence, but each rehearses muscles we will need when it arrives: plural‑value alignment, incentive redesign, fast feedback loops.

To nurture and grow these pockets of protopia we need to invest in an ecosystem of imagination.

History’s biggest leaps from powered flight to antibiotics to the Internet, began as futures someone dared to describe in detail. (Jules Verne helped invent the helicopter. Star Trek’s pocket “communicators” inspired Motorola’s first flip phone. Humanoid robots are coming, and Isaac Asimov says hi)

If we can’t articulate a desirable future, we should not expect to land there by accident.

If you build products, respect your users and focus on the human outcome your program is meant to improve, recognize that you are playing a team game and lets others push the same future forward, one commit at a time.

If you make policy, create spaces where multiple futures can be prototyped simultaneously, fund slow-thinking forums immune to hype cycles.

If you tell stories, show us worlds getting better by degrees. Make protopia as textured and complex as any dystopia. Make hope as vivid as doom.

If you are simply alive in 2025, practice future-literacy. Talk about the future with your friends, partners, kids. And when you do, talk about how you have the agency to change it. Teach your kids to critique sci-fi endings, what would they have done differently, how could it have ended better?

I am an optimist, in case it wasn’t obvious already.

And despite what 24 hour news cycles, doomscrolls and “experts” on X & WhatsApp tell us - the truth refuses to surrender.

A girl born today has a better chance of learning to read than any generation before her. Two-thirds of the world now enjoys access to safe drinking water, up from half in 2000. The annual battle‑death rate remains a fraction of what it was during the Cold War.

The lives of most humans through history were steeped in loss, fear, and arbitrary power. Ours, while imperfect, are orders of magnitude safer and healthier. Optimism is not denial; it is perspective plus agency

On or around December 1910, human character changed. I am not saying that one went out, as one might into a garden, and there saw that a rose had flowered or a hen had laid an egg. The change was not sudden and definite like that, but a change there was, nevertheless …"

Virginia Woolf writing about the arrival of Modernism

On or around December 2022, human character changed again, the sense that reality itself could be re-architected that modernity hinted at is now evidently demonstrable.

Intelligence itself, long bound by biology, is preparing to fork its own codebase.

The question is whether we will co‑author the commit message or let it be auto‑generated by market incentives.

Progress is not inevitable; it is written and re-written, draft by painful draft.

It’s time to pick up the pen.

Thanks for reading The Day After Tomorrow! This post is public so feel free to share it.

.png)