The Works in Progress print edition will be shipping soon. Subscribe this week to receive Issue 21 as soon as it ships. You’ll get six full-color editions sent bimonthly, plus subscriber-only invitations to our events.

Soap is an ancient innovation: a Sumerian text from around 2200 BC gives a basic recipe for making soap. But early soap was mostly used to wash clothes, and sometimes for bathing. For kitchen dishes and eating utensils, people made do with cheaper and more readily available materials.

Sand has been used to scour dishes for thousands of years. It’s easy to find and great for physically scrubbing food detritus off of wooden or metal dishes. Many other natural abrasive substances have been used too. In India, traditional dishwashing materials ranged from jute fiber to rice husk to eggshells. In England, the horsetail plant, Equisetum hyemale has been known as ‘scouring rush’ or ‘pewterwort’, and John Gerard’s 1597 botanical reference book explains that the plant’s roughness ‘is not unknowen to women, who scowre their pewter and wooden things of the kitchen therewith’.

When scouring with physical abrasives was not enough to remove grease, the women described by Gerard could turn to the chemical properties of ash. Wood ash contains potassium carbonate. When it’s leached in water, it creates lye, an alkaline solution of potassium hydroxide, which can be combined with an oil or fat to form soap. In essence, washing a greasy dish with ash and water creates soap on a micro scale. The use of wood fires to heat homes and cook food meant that ash was available in abundance.

That would change in the early modern period, when households started switching from wood to coal. In London, the shift began around 1570 and was almost complete by 1600, making wood ash more scarce. Without ash to cut the grease, Londoners began using ready-made soap to wash dishes.

Soap introduced a new requirement: hot water. Hot water is helpful when washing with ash, but not needed when scouring with sand. In fact, Ruth Goodman, in her book The Domestic Revolution, reports that for sand-scouring, cool water actually works better. The soaps available at the time, by contrast, only worked effectively when activated by hot water. So the new soap-and-hot-water dishwashing regime was both prompted by the switch to coal and fueled by it.

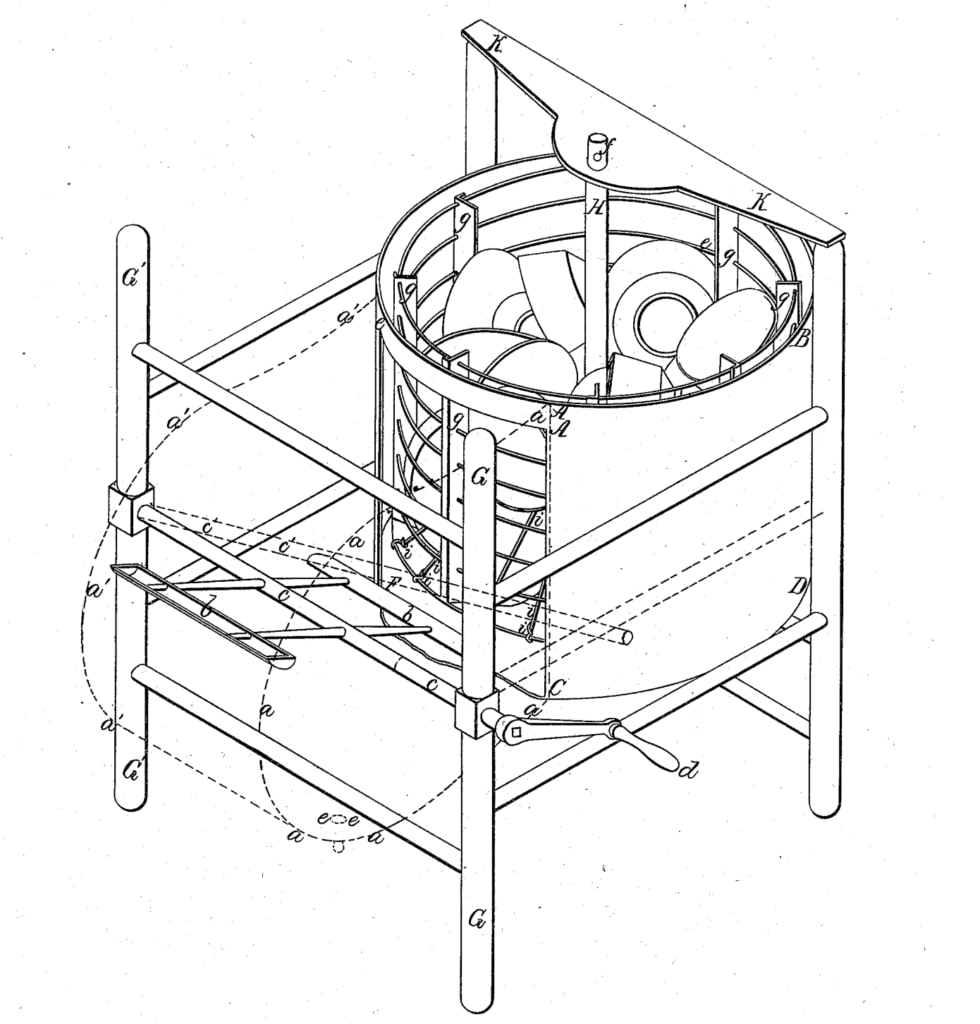

In the mid-nineteenth century, inventors made the first steps towards mechanizing dishwashing. In the United States, the first dishwasher patent was granted in 1850. This dishwasher (or ‘table furniture cleaning machine’, as its inventor called it) was a large tub with a rotatable dish rack in one half and a paddle wheel in the other half. The user would load the dishes, heat up some water separately, pour the hot water into the machine, and then crank the paddle wheel with one hand to throw water onto the dishes, while their other hand (or an assistant) spun the dish rack. This was an awkward process, and probably also ineffective – the water splashed onto dishes with the little scoop wouldn’t have enough power to replace scrubbing.

In the next patent for a dishwasher, granted 13 years later in 1863, inventors Gilbert Richards and Levi Alexander proposed a stationary dish rack around the edges of a tub, with curved paddles attached to a vertical shaft in the middle. The operation would be similar: heat water, pour it into the tub, hand-crank the paddles to splash water onto the dishes.

Richards and Alexander must have realized that this process couldn’t fully replace scrubbing, because their patented machine also had a little side compartment where the operator could scrub one dish at a time using a completely separate mechanism: with one hand, holding the dish up to the revolving sponge-arms; with the other, cranking the handle to spin the sponges.

Their design was the beginning of a flurry of new dishwasher patents. Between 1863 and 1888, the US Patent Office granted more than 60 patents for dishwasher designs and improvements. Many of the designs were remixes of the same key elements: dish racks, tubs of water, various hand-cranked mechanisms for splashing the water up onto the dishes. Some designs involved submerging the entire dish rack, and spinning it around underwater to clean the dishes. Others expanded on the ‘revolving sponge’ idea: for example, a machine that sandwiched a plate between two brushes, and dipped the whole plate-and-brush sandwich underwater while the brushes rotated in opposite directions. Still others invoked centrifugal force, conveyor belts, or springs.

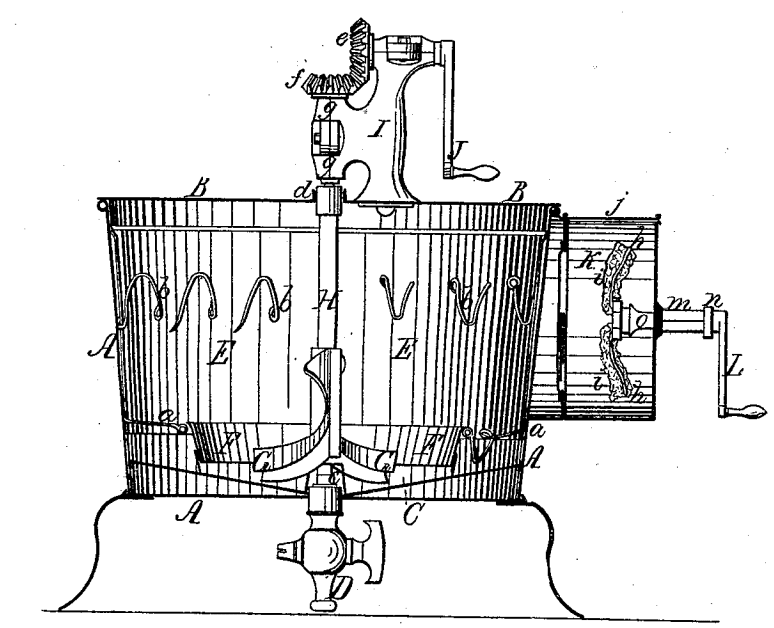

None of those designs caught on. Instead, the first commercially successful dishwasher, created and sold by Josephine Garis Cochrane, used jets of pressurized water to clean the dishes. Although Cochrane was not the first to propose using water jets, she was granted seven US patents for various other dishwasher designs and improvements. Her first patent, in 1886, covered the idea of using two separate water systems: one for soapy water, and one for clean hot water to rinse away the soap. A small lever on the outside of the machine controlled whether it was in washing mode or rinsing mode, engaging the appropriate pump and channeling water to return to the appropriate tank to be reused.

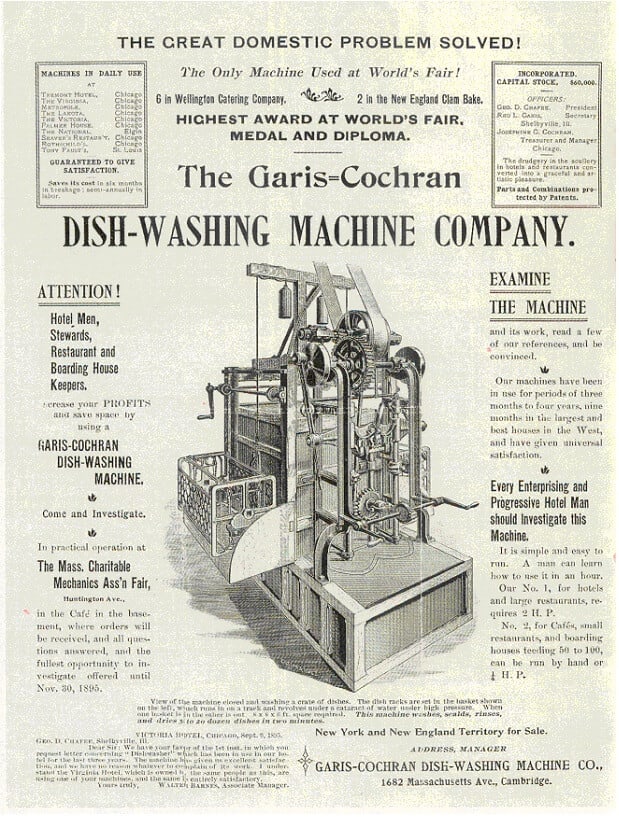

Unlike previous dishwasher inventors, Cochrane manufactured her machine at scale and built a company. She established her factory near Chicago, and traveled throughout the Midwest to demonstrate and sell the machines. The 1893 Chicago World’s Fair was a great showcase for her dishwashers: they were on display in the Machinery Hall and in the Women’s Building, and they were in use behind the scenes at the fairground’s restaurants. They were also installed in many of the hotels that Chicago built for World’s Fair visitors.

None of those designs caught on. Instead, the first commercially successful dishwasher, created and sold by Josephine Garis Cochrane, used jets of pressurized water to clean the dishes. Although Cochrane was not the first to propose using water jets, she was granted seven US patents for various other dishwasher designs and improvements. Her first patent, in 1886, covered the idea of using two separate water systems: one for soapy water, and one for clean hot water to rinse away the soap. A small lever on the outside of the machine controlled whether it was in washing mode or rinsing mode, engaging the appropriate pump and channeling water to return to the appropriate tank to be reused.

Unlike previous dishwasher inventors, Cochrane manufactured her machine at scale and built a company. She established her factory near Chicago, and traveled throughout the Midwest to demonstrate and sell the machines. The 1893 Chicago World’s Fair was a great showcase for her dishwashers: they were on display in the Machinery Hall and in the Women’s Building, and they were in use behind the scenes at the fairground’s restaurants. They were also installed in many of the hotels that Chicago built for World’s Fair visitors.

In fact, although Cochrane had imagined her dishwasher as an aid to women managing households, she found that restaurants and hotels were her core customers. The dishwashers were expensive for a household: we have records listing them for $350 in 1911 (equivalent to about $12,000 today). Restaurants and hotels, with their industrial quantities of dishes to wash, benefited more from the purchase.

Access to utilities was also a factor. Cochrane’s first patent described a machine that the user pours hot water into, but by 1903 her dishwasher received its hot water from a hot-water-supply pipe. Similarly, the first design was powered by hand, but by 1894 the machine was ‘driven by an engine or any other suitable motor or power’. These changes made the machines easier to operate and more effective, but were also prohibitively expensive for many households. When Cochrane was selling her dishwashers around the turn of the century, fewer than ten percent of American homes had electricity, and even fewer would have had electricity, piped hot water, and the money for the up-front cost of a dishwasher. With all of these barriers to adoption, the dishwasher didn’t become a common appliance during Cochrane’s lifetime.

But by 1925, electricity had reached more than half of American homes, and by the 1960s it was close to universal. Over the following decades, dishwashers were widely adopted. They’re still not nearly as ubiquitous as electricity, but the share of homes with dishwashers has grown from about 7 percent in 1960 to about 73 percent in 2020.

Alongside other household appliances and cultural shifts, dishwashers have allowed Americans, especially American women, to spend significantly less time on housework. In 1965 (when 14 percent of families had dishwashers), the average married American woman did 34 hours of housework per week, while the average married man did 5. For comparison, in 2010 (when 70 percent of families had dishwashers), the average married man did 10 hours of housework per week, and the average married woman did 18. This certainly shows shifting gender dynamics, but it also shows that a typical married couple spends 11 fewer hours per week on housework than they did in 1965.

In addition to saving time, modern dishwashers save water and energy. Studies collected by a group of California utilities companies found that washing dishes by hand uses about three times as much energy, and seven times as much water, compared to washing them in a dishwasher. Environmentalists now aim to convince more people to buy dishwashers, use them regularly, and trust them enough to load the dishes without pre-rinsing.

This is a case where resource efficiency happily goes hand-in-hand with domestic ease: we don’t have to gather horsetail for scouring, we don’t have to heat water over a coal fire, and we don’t even have to rinse our dishes before we load the dishwasher.

Erin Braid is a writer and researcher.

Thanks for reading The Works in Progress Newsletter!

.png)