An 81-year-old woman with advanced Alzheimer’s lies in an Icelandic retirement home. She hasn’t recognized her family or spoken a word to them in over a year. Her son Lydur sits at her bedside, working on a crossword puzzle - not expecting any interaction, just being present.

Suddenly, she sits up. She looks him directly in the face.

“My Lydur,” she says. “I am going to recite a verse to you.”

And then she does, loudly and clearly:

Oh, father of light, be adored.

Life and health you gave to me,

My father and my mother.

Now I sit up, for the sun is shining.

You send your light in to me.

Oh, God, how good you are.

After which she lies back down and never talks again, dying soon thereafter.

This case, reported in Nahm et al., (2011), is an example of terminal lucidity: an unexpected return of cognitive function in patients with severe dementia (or other brain damage) occurring shortly before death.

As a neuroscientist, my first thoughts when encountering reports like this are that they can’t possibly be real.

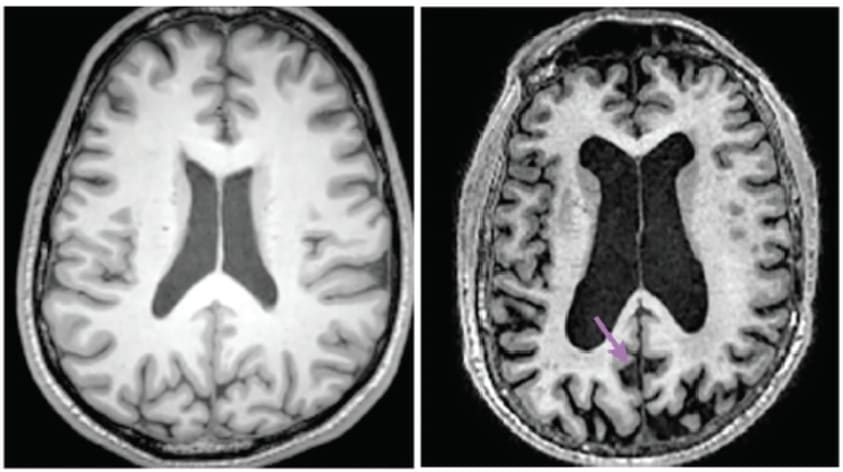

By the time patients with severe dementia actually die, their brains are catastrophically damaged. They typically show no signs of recognizing family members. They often haven’t responded meaningfully to their environment in months or years. Their brains are riddled with plaques and tangles. And they’ve lost 20-50% of their synaptic connections - so much that their brains have visibly shrunk on MRI scans.

On top of this existing damage, the dying process itself is hardly optimal for brain function. Most dementia patients die from infections, such as pneumonia from inhaling material into their lungs, or sepsis originating from bedsores. As bacteria multiply and the patients’ weakened immune systems struggle to respond, their brains suffer oxygen deprivation and exposure to inflammatory toxins. Everything we know about neuroscience says this should make cognition worse, not better.

And yet, terminal lucidity keeps being reported. In retrospective reports, 60-70% of dementia caregivers say they’ve witnessed at least one patient return to lucidity in the days before death (though given caregivers may observe many deaths over the years, the actual per-death incidence is potentially much lower). The only prospective study, which followed 100 hospice deaths, found it in 6% of cases. That’s not ubiquitous, but nor is it rare - in the US alone, it would mean around ten thousand cases per year.

As Michael Nahm, one of the key researchers in the field, puts it: “terminal lucidity… is more common than usually assumed, and reflects more than just a collection of anecdotes that on closer scrutiny emerge as wishful thinking.”

It might not be immediately obvious, but if terminal lucidity is real, it has profound implications for neuroscience and medicine.

We increasingly understand how memories are physically stored in the brain. Forming new episodic memories requires the hippocampus. Retaining memories depends on neural circuitry maintaining particular synaptic connection strengths. In animal models, selectively destroying these synapses can erase specific memories. In humans, as dementia progresses and these neural structures physically deteriorate - neurons dying, synapses disintegrating, the hippocampus shrinking - memory reliably worsens.

So when a woman who hasn’t recognized her son in a year suddenly calls him by name and recites a childhood poem, where have those memories been physically stored? If the neural substrate we thought was necessary for memory is degraded, but the memories can still be accessed, then either our understanding of memory storage is fundamentally wrong, or there’s some resilient substrate we haven’t identified yet.

This isn’t just academically interesting - understanding terminal lucidity could revolutionize dementia treatment. Right now, we’re already spending over a trillion dollars annually caring for 60 million people with dementia worldwide. Despite this, our best treatments like Lecanemab cost around $30,000 per year, in exchange for, at best, a minuscule reduction in the rate of disease progression (let alone actually reversing the decline).

But if terminal lucidity is real, it means there are naturally occurring conditions under which even severely damaged brains can have their function restored. Instead of trying to prevent amyloid accumulation - an approach that has largely failed despite billions invested - we could study what’s happening during these episodes. If a dying brain can indeed spontaneously access “lost” memories, perhaps we could induce a living brain to do the same.

The implications for brain preservation are equally significant. Severe dementia suggests irreversible identity loss, and if the person you were is already permanently gone, there’s little point in subsequently preserving your brain for attempts at future revival. This creates a terrible dilemma: anyone serious about preservation needs to consider undergoing the procedure before dementia progresses too far, raising obvious legal and personal challenges.

But if terminal lucidity is real, it suggests dementia might not be primarily a disease of memory loss, merely one of memory retrieval. The information is still in there, just inaccessible under normal conditions. For preservation advocates, any technology sophisticated enough to perform revival would likely be able to solve retrieval problems too. It would certainly be a great relief to already have precedent for people being recovered from brains that appear catastrophically damaged.

Still, it would be easier to believe terminal lucidity was real if there weren’t such emotionally compelling reasons to want it to be real.

Watching a parent slowly lose themselves without ever having a final chance to say goodbye is devastating. People crave the deathbed scenes from books and movies: the elderly relative surrounded by family, pronouncing meaningful final words before peacefully expiring. But in reality, there’s often a long gap between when someone loses the ability to communicate and when they die - days, weeks, months, or even years in severe dementia.

This creates exactly the conditions for observer bias to flourish. Family members sit at bedsides desperately hoping for one last moment of connection, watching for any sign - however small - that their loved one recognizes them or is trying to communicate. They have time to rehearse what they wish they could say, and dream of what they wish they could hear back.

Consider this case from a 2024 study:

“[A 12-year-old girl with cancer, who had been unresponsive for months, was declared dead]. Just before this event, her mother noted that the patient opened her eyes, and mouthed “I love you” and “I’m ready to go home,” and blinked her eyes to answer yes/no questions. Her mother commented that she had not “seen her eyes” in several months and appeared to consider these moments as signs of life, despite her daughter’s medical condition.”

No one wants to ask a grieving mother about how confident she truly is that her dying daughter told her she loved her. But from a scientific perspective: was the girl actually forming words, or were those involuntary muscle movements interpreted as speech? The same question applies to a grandmother who seems to smile and nod (postural reflex?), or a dying spouse who squeezes a hand when told “I love you” (muscle spasm?).

The problem is that nearly all reports of terminal lucidity come from exactly these sources: emotionally invested family members or caregivers with strong motivations to perceive communication where there might be none, no scientific training to distinguish meaningful behavior from reflexes, and no blinding to prevent bias.

The only study I’ve found that actually tries to characterize what these episodes look like is Griffin et al., (2024), which surveyed family caregivers who reported witnessing lucid episodes in dementia patients. They found 51% of episodes involved communication that “made complete sense,” with another 32% making “some sense.” Although, keep in mind that 48% of episodes occurred at least six months before death, with only 18% happening in the final week. Most of these weren’t ‘terminal’ lucid episodes at all - they’re potentially just the normal cognitive fluctuations that occur throughout dementia progression.

So far then, we’re left almost entirely with anecdotal reports from biased observers, collected retrospectively, with no objective verification, mostly describing ambiguous behaviors that could arguably be explained by wishful interpretation.

And yet.

The phenomenon has been consistently reported across centuries and cultures. Although anecdotal, case reports of patients who haven’t spoken in years suddenly engaging in complex conversation are hard to dismiss as mere muscle spasms or observer bias. The single prospective study found it in 6% of deaths, suggesting something is happening beyond pure confabulation.

I genuinely don’t know whether terminal lucidity exists. Given that, the appropriate response is neither to credulously accept every report nor to dismiss the phenomenon entirely either - it’s to actually study it properly. Which brings us to what might be happening if any of this is real.

No one has actually studied the neuroscience of terminal lucidity while it’s happening - no EEG recordings, no brain imaging, no blood work during episodes. So any explanation is necessarily speculative. But we can make educated guesses based on known and related phenomena:

Brain swelling reduction

Dying patients often develop brain swelling from multiple causes: electrolyte imbalances, low blood protein, kidney or liver failure, inflammation, or damage to the blood-brain barrier. This swelling compresses brain tissue and reduces blood flow, starving neurons of oxygen and glucose. The result is the familiar progression of terminal delirium: confusion, then sleepiness, then coma, then death.

But in their final days, many patients stop eating and drinking entirely. The resulting dehydration could reduce brain swelling, allowing blood flow to increase and temporarily restoring some cognitive function - a brief window of lucidity before the dying process continues. It’s a simple mechanism: lower intracranial pressure means better perfusion, means more oxygen and glucose in the brain, which in turn means more functional neurons.

This is testable. If swelling reduction is the mechanism, we’d expect terminal lucidity to correlate with dehydration, and potentially with certain causes of death more than others.

Paradoxical network effects

Alternatively (or additionally) something stranger might be happening with how brain networks respond to extreme conditions.

Normal consciousness requires precise neurochemical balance. Too much excitation causes seizures. Too much inhibition causes unconsciousness. Wakefulness depends on brainstem neurons continuously releasing neuromodulators like acetylcholine, noradrenaline, and histamine into the cortex. When this system breaks down in a damaged or dying brain, people typically become progressively less responsive.

But sometimes, perturbing a broken system can temporarily fix it. If you’ve ever gotten a glitchy electronic device to work by hitting it, you’ve seen how pushing a malfunctioning system into an unusual state can accidentally restore function.

Maybe something similar happens in dying brains, where under extreme or unusual conditions, damaged neural networks can sometimes spontaneously reorganize in ways that temporarily restore function. One research paper speculates that dying brains might generate “spontaneous network integration manifesting as lucid behavior” through “rapid and nonlinear synchronisation.” Translated from Academic into English, this means “we think weird things might happen in a dying brain that briefly improve function, but we don’t really know what.”

If terminal lucidity is real, it should be one of the most intensively studied phenomena in neuroscience. Instead, it’s barely studied at all. This is wholly unacceptable, given it’s far from impossible to investigate. The studies we need are straightforward, if ethically sensitive:

With informed consent from patients and families, video record supposed lucid episodes in people with advanced dementia or other terminal conditions. Have researchers who are blinded to each patient’s medical status and proximity to death score the recordings for evidence of lucidity. Compare these to baseline videos of the same patients, and to control recordings from other dementia patients who don’t experience supposed lucid episodes.

If independent, blinded raters confirmed that genuine improvements in cognition were occurring, follow-up studies could investigate what’s actually happening physiologically: neuroimaging to measure brain activity patterns, blood work to check for electrolyte changes, continuous monitoring to track the lead-up to episodes. If we could identify reliable precursors or correlates, we might be able to induce similar states safely in living patients.

Yes, this requires asking grieving families for permission to record and monitor their loved one’s final days. That’s difficult. But patients routinely consent to organ donation and whole-body donation to science - procedures far more invasive than video cameras and EEG caps. If anything, families motivated by the possibility of helping future dementia patients might welcome the chance to contribute to research.

And to be fair to researchers in this field, systematic surveillance with blinded scoring was proposed at a 2018 National Institute on Aging workshop specifically convened to examine terminal lucidity. A 2021 Guardian article even reports there are six funded studies ongoing, and that one of these, led by Sam Parnia at NYU Langone Medical Center, plans to monitor 500 dementia patients at end of life using continuous EEG with synchronized video recording.

Yet as of 2025, we still lack the rigorous evidence needed to answer the basic question of whether terminal lucidity is real, let alone understand its mechanisms. Meanwhile, we continue pouring billions into marginally effective amyloid-clearing drugs and performing study after study on Alzheimer’s mouse models that fail to translate to humans. A fraction of that funding redirected to studying terminal lucidity - a potentially naturally occurring phenomenon that might reveal entirely new therapeutic approaches - seems like an obviously better investment.

Note: just as I was finalising this post, the results of one of these new studies was published. Gilmore-Bykovskyi et al. (2025) prospectively monitored 20 hospice patients with advanced dementia using continuous video recording and found lucid episodes in 3 of them. This is great to see, but it does come with significant caveats: the study wasn’t blinded (the same family and clinicians who witnessed events also scored them) and the sample was tiny. Still, it strengthens the case for terminal lucidity being real, and provides strong justification for larger, blinded studies.

To me, the gross neglect that is terminal lucidity having been ignored for so long reflects a deeper issue: death and dying are drastically understudied across medicine and neuroscience.

Sure, from a traditional medical perspective, there’s little reason to investigate what’s happening in a terminal patient’s brain during their final hours, or how quickly neural decay occurs after blood flow stops. The patient is already doomed at that point, and palliative care’s focus on comfort and dignity doesn’t require detailed scientific understanding.

But terminal lucidity is a rare case where understanding what happens during dying matters to more than just brain preservation advocates. If severely neurologically damaged patients can spontaneously access “lost” memories and abilities under certain dying conditions, we need to know what those conditions are, why they work, and whether we can replicate them safely. However unlikely it is that terminal lucidity is truly real, something with such broad implications - for both dementia-hating normies and brain-preserving weirdos - shouldn’t be ignored.

.png)