Imagine that your 8-year-old son comes home buzzing with excitement about a brand-new amusement park that just opened, called “Neopark.” He heard about it at school, and his friends say it’s amazing. Apparently, kids run around between thousands of rides — all of which are free!

Curious, you decide to take him. At the entrance, an employee hands you a sticky microchip and leads you into a dim back room. He invites you to sit down in a comfortable-looking recliner next to dozens of other kids and adults in recliners. The employee reassures you the park is perfectly safe, even for children as young as five, thanks to the age-based safeguards they’ve installed. He tells you to put the chip on your temple. You oblige, close your eyes, and in an instant you’re inside a vast world of glowing gates, wild challenges, and endless rides.

There are no lines and no closing time. You later notice that there are no guards, no police, and nobody in charge.

The park is bright, loud, and chaotic. People sprint between portals — tank battles, dance-offs, fantasy quests — each with different rules. The park runs on its own currency, which kids spend on flash deals, mystery boxes, and spinning wheels promising rare prizes.

Everyone is wearing a full-body suit that makes them look like a cartoon character, and everyone is the same size. Everyone is wearing a mask, so you can't tell who anyone is, or how old they are. Many seem to be wandering aimlessly around the park, striking up conversations with anyone they can find. One person who appears — judging by his movement patterns, likely an adult man — picks up your son, carries him towards a nearby ride, and then asks for his phone number. Another invites him to a workshop “just outside the park.”

Some rides are clearly meant for adults, and some (but not all) of those rides have signs stating minimum ages, but there’s nobody around to enforce those limits, so children as young as your son can be found on every ride. In one game that you wander into with your son, you’re trained to hide a dead body after a murder. Your son then enters a game by himself and requests a private therapy session from another guest at the park. In the next one you see a group of people holding Nazi flags next to what looks like a concentration camp. In another, you enter a classroom and find a teacher having anal sex with a student. In the last game you wander into, a shooter with an AK-47 opens fire in an elementary school.

The park is always changing. The haunted house that you saw an hour before has been replaced by a dating game. The pirate ride adds a stripper pole beneath the poop deck while you’re exploring the ship.

Six hours pass, and you’re ready to go. Your son is red-eyed and begging for one more ride. You tell him he doesn’t have a choice, it’s dinner time. You walk to the exit gate and wake up back in the dim room.

Users are encouraged to take the chip home, allowing them to access the park from anywhere in the world. Your son begs you to let him bring his chip home. He says all his friends have one, and he’ll be left out if he doesn’t. He adds that every other parent allows it. (Later, you find out that many parents don’t even know their kids have a chip. You also learn that kids often put the chips on during the bus ride to school, and during the school day when teachers aren’t looking, and late at night when they are supposed to be sleeping.)

But you hold the line. This is insane, you think. Who would let their children play at a place like this?

As surreal as it sounds, this isn’t an entirely fictional story. It’s a glimpse into what millions of kids experience daily in today’s most popular online games. In fact, every disturbing game we mentioned in our story is an actual game that exists (or that recently existed) on Roblox. And most parents have never stepped inside.

Video games have been around since the late 1950s, but something shifted during the first decade of the 2000s, as the bandwidth and speed of the internet grew rapidly. Alongside the rise of early social media platforms like MySpace, Facebook, and Twitter, a new kind of video game emerged — one that didn’t end.

Instead of offering a fixed storyline or campaign, these games kept evolving. They were built on a new model called Games-as-a-Service (GaaS) — where games were continuously updated with new content, features, and events to keep players engaged and coming back. These games were typically (but not always) Free-to-Play (F2P) — at least when you started. And they were in sharp contrast to the games that came before, which were typically sold as discrete complete products with a beginning, middle, and end.

World of Warcraft (2004) was among the first of these games to popularize online multiplayer gameplay at scale. It offered not just gameplay but community, identity, and endless progression. It required an initial CD-ROM purchase, and an internet connection, and a monthly subscription. Its connection to the internet enabled constant updates and dynamic worlds.

This momentous shift in gaming accelerated in the late 2000s with many games becoming F2P by monetizing in-game advertising. Users now paid for games over time with their attention (to advertisements) and their in-game purchases.

Table 1 below highlights some of the key differences between pre-purchased games and GaaS/F2P titles.

By 2018, the most popular video games had evolved into platforms that blended interactive social media dynamics (e.g., social features such as ephemeral messaging and status signals) with the content-delivery model of streaming services (e.g., subscription-style models). Leading the list were Minecraft, Fortnite, and Roblox.

Minecraft is arguably the safest of the three, partly because it isn’t Free-to-Play. It became a global favorite in 2011 with its open-ended, block-building format where players create, explore, and survive in both user- and house-generated worlds. Fortnite rose to prominence in 2017 as a fast-paced battle royale, boosted by viral dance trends and early Marvel collaborations that helped turn it into a cultural sensation. By 2018, it expanded into user-generated “islands,” offering thousands of custom maps that all center around the same shooter-style gameplay. Roblox, which launched in 2005, functions more like a streaming platform than a traditional game, giving its primarily under-18 user base access to millions of user-created experiences — each with their own rules, ‘purpose’, and social dynamics. All three thrive on being social, constantly evolving, and driven by their users.

This model came to dominate the industry due to its limitless revenue potential, ability to optimize user engagement through dynamic feedback, and mass accessibility granted through the F2P model.

Games built on the now dominant Games-as-a-Service (GaaS) model are outperforming all other video games in history — especially when it comes to use by minors. The open-sandbox games Minecraft and Fortnite each attract roughly 30 million monthly active users (MAU) under the age of 18 from around the world. Both are dwarfed by Roblox, which currently hosts about 304 million MAU under 18. According to Roblox’s own reports documented by the New York Times, as of 2020, about 75% of US children ages 9-12 were active users on the platform. As of 2024, 65% of parents with children under 14 report their child plays Roblox.

The average age of gamers is dropping, with platforms like Roblox explicitly targeting younger children, and with boys being the most consistent and profitable users. On average, boys spend two and a half times as many hours gaming per day as girls do and 40% of boys report playing every day, compared to just 10% of girls. Beyond time spent, male players are three times as likely as girls to make in-game purchases, and more than twice as likely to identify as “gamers.”

Taken together, the effort to attract younger and more diverse users, while simultaneously deepening engagement with traditional gamers, is reflected in the new model’s ability to open the gaming world to anyone with a device and an internet connection, and be extremely profitable.

The GaaS model incentivizes the mass adoption of a given platform, with the intention that a subset of heavy gamers within each group will spend … a lot.

The impact of these two major pillars of modern gaming — GaaS and Free-to-Play — can’t be fully understood without considering the third pillar of today’s online gaming experience: user-generated content (UGC). A foundational element of platforms like Roblox, Fortnite, and Minecraft is that many of their games are not built by professional studios, but by other users.

UGC platforms instead serve as infrastructure; they provide a sandbox in which anyone can create, publish, and share new game experiences with the world. This remarkable innovation lowers the barrier to entry for aspiring developers and allows millions of users to participate in the creative process of game design.

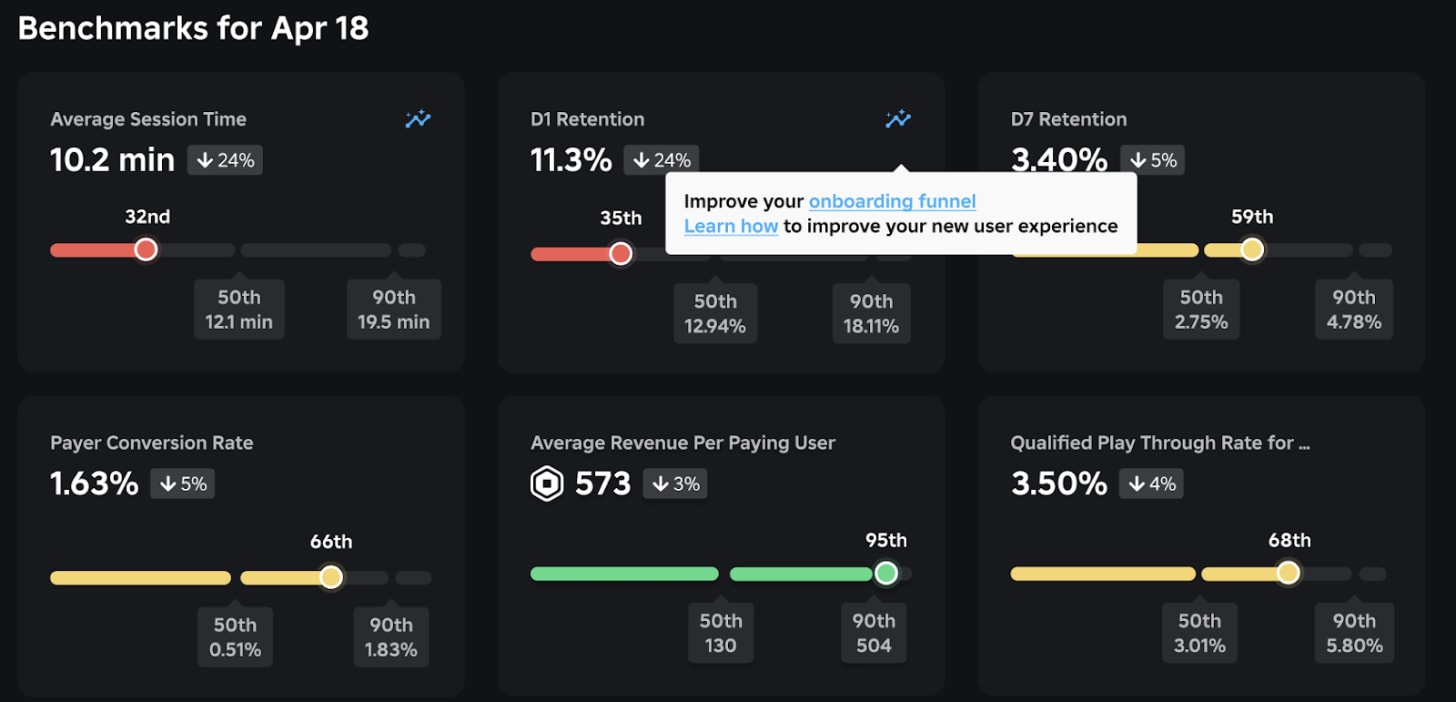

Yet this model also introduces a large and expanding set of new risks. For one, UGC platforms now have the responsibility of relentless content moderation — with, for example, 15,000 new games uploaded to Roblox every single day in 2022. In addition, the incentives for game developers are aligned for engagement rather than safety. Within Roblox, the developers of UGC are compensated in Robux — a digital currency that can be exchanged for real money — based on engagement (hours users spend in their game and how often they return to the game) and how much Robux users spend while on their game. Roblox provides creators with detailed analytics (see image below) and encourages them to "optimize retention, engagement, and monetization." In other words, creators are not incentivized to build what’s meaningful or healthy for children. They are incentivized to build what keeps kids coming back and spending. Roblox therefore offers three of the most harmful features of standard social media: widespread interaction with anonymous adults, wildly inappropriate content, and addiction-by-design.

The abundance of endless content and games helps keep users engaged on platforms, but it’s not the only reason they stay. What builds loyalty to a platform from game to game is the avatar.

Most popular GaaS games center the gaming experience around an avatar: a persistent digital identity that players customize, upgrade, and grow attached to over time. Unlike earlier characters who disappeared after the credits rolled, today’s avatars persist across games and seasons. Players invest in them emotionally and financially. It’s not just about the games anymore. It’s about the person they’ve become within them.

The shift to avatars is an important piece of the larger movement that changed gaming from a goal-driven activity to a continuous state of being. Platforms like Roblox don’t offer one game, but 40 million user-created ones. Players’ avatars are the vehicle through which they experience the game environment. They are also the vehicle through which other users experience them.

The rise of smartphones supercharged the shift to F2P/GaaS gaming. With the launch of the iPhone in 2007 and the App Store in 2008, mobile Free-to-Play games like Angry Birds (2010) and Candy Crush (2012) took off. But it was Fortnite (2017) that brought mobile gaming to new heights. By introducing crossplay — allowing players to carry their avatar and progress across devices, including mobile — Fortnite enabled a seamless, always-available gaming experience. Crossplay unlocked new ways to monetize across every screen a child might own. Crossplay made it far easier for gaming companies to reach most children during most of their waking hours.

By the early 2020s, pre-purchase game monetization had been pushed to the margins. By 2022, F2P games made up over 80% of all global gaming revenue. Just 12 years earlier, the F2P model had constituted less than 20% of industry revenue.

This shift is similar to what happened with airline pricing — except in this case, the plane ticket is free and there are no security checks at the gate. Once you're on board, nearly everything costs extra: food, carry-ons, seat selection and anything beyond a small cup of water and using the restroom. Only the most prepared, frugal, or strong-willed passengers avoid these charges, which are designed to exploit basic impulses and needs once you’re already in motion. We’ve put together a list of common in-game monetization strategies which can be found here.

With smartphones came deeper integration of gaming with social media.

Social platforms like Twitch and Discord (both of whose user bases surged during the 2020 pandemic and continue to be used by at least a third of teenage boys) are now an integral part of the gaming experience. Whether through third-party integrations or direct links, these apps seamlessly connect with most major online games.

Some platforms, like Roblox and Minecraft, try to limit minor users' access to outside social media platforms like Discord and Twitch via AI-based chat filters. But gaming culture now exists in a network of platforms that regulation can’t keep up with (like trying to outlaw smoking at Woodstock). A game might limit chat features, but it only takes a quick Google search for a kid to land in an unofficial “modding” forum, Discord server, or Twitch stream where the real culture of a game lives and breathes. As is so often the case with social media, children are conversing with anonymous strangers on these platforms.

Gaming chats have become the new boys’ locker room. For many boys, this locker room is their only place to talk smack, blow off steam, and bond. Normal adolescent behaviors. But when the locker room has anonymity, no walls, and anyone is allowed in, the stakes change. Porn is easy to find and easy to share. In these unfiltered and unregulated spaces, adults contact children and extreme content can flow freely: bestiality, violent porn, animal abuse, self-harm, stabbings, and an array of extreme ideologies to name a few.

Discord, the most popular chat app in the gaming world, is an online space known for its volatility, inhabited by millions of teenage boys and adult men.

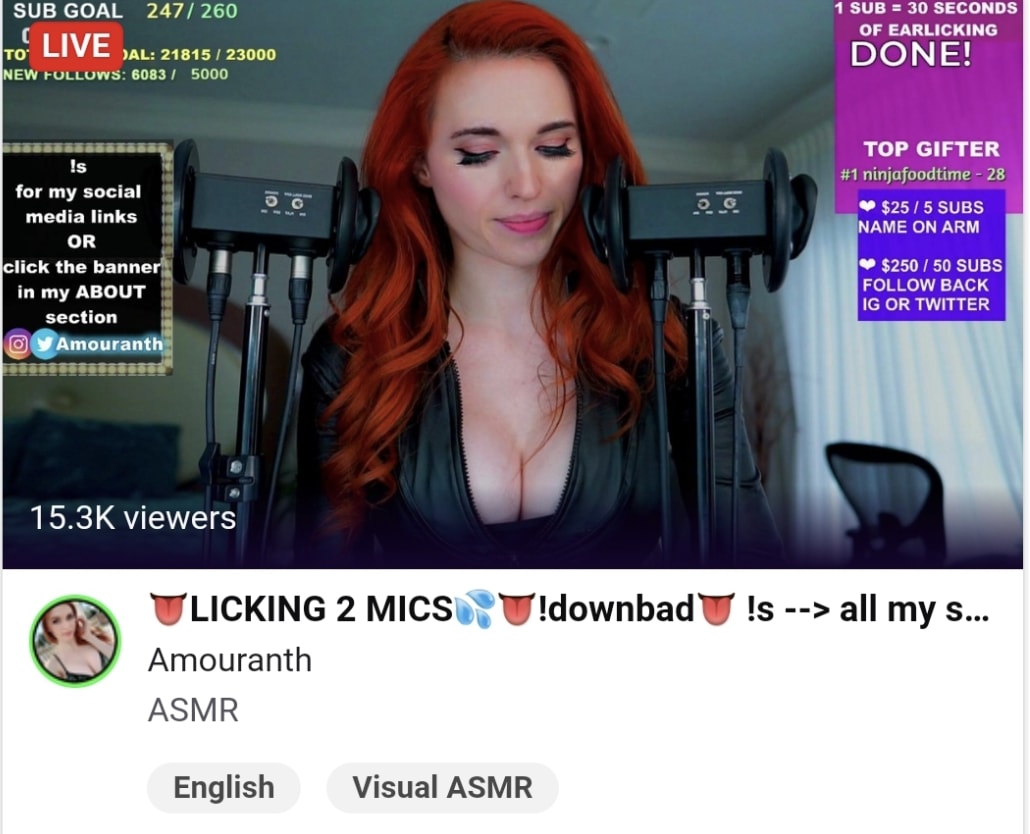

Twitch has its own set of issues. Its primary purpose is to stream video gameplay, but many top streamers (who tend to beattractive young women in revealing clothing) also run adult content accounts — sometimes side by side with their gaming streams.

Being a gamer in 2025 isn’t just about playing video games. It means being enmeshed in a web of social platforms, influencers, private chats, and high-engagement content. This is the chaotic, exciting, and sometimes degrading world we were trying to convey in our opening story.

The new model of gaming (which integrates GaaS, F2P, and UGC to varying degrees) has created a continuous, open-ended transaction between the game and the gamer. The game is never finished, and the spending never stops. To opt out of spending one’s time and money is to be marked as an outsider within the game's economy and culture, which are intentionally intertwined.

A traditional paid game usually requires a parent’s attention at the point of purchase. There’s a moment when approval is needed, a credit card is required, and some level of oversight is naturally built in. But when a child can log in to a game for free, build an identity within it, and immerse themselves in a virtual world — only asking for money after they’re already emotionally invested — the playing field has changed. Parents are no longer the first line of decision-making. Too often, they are brought in only after the hook is set, asked to fund a digital life they never approved of. Of course, parents can revoke access at any time, but by then, the emotional investment has been made and the child won’t want to waste it without a fight. It’s far easier to prevent access than it is to take it away once it’s become an important part of a child’s social life.

This new model of gaming has produced a new set of harms, which parents need to understand.

There are a multitude of harms associated with modern gaming, some caused or amplified specifically by the shift from pre-purchased games to F2P GaaS games. Here we present eight of them. In these sections, we occasionally include real life examples to illustrate the harm.

According to a recent Common Sense Media report, 8–12-year-olds spent an average of 2 hours and 18 minutes per day playing video games in 2019, and that increased to 2 hours and 27 minutes in 2021. This report did not specify what percentage of children spent this much time gaming. However, a 2015 report found that one-in-three of boys and one-in-ten of girls in this age group played for at least two hours daily, with ten percent of boys exceeding four hours. Among older adolescents (ages 12–18), a 2021 survey found that 57% of boys and 36% of girls reported gaming for at least 3.5 hours per day.

Note that this gaming is frequently displacing sleep, playing outdoors, socializing with others, and reading, contributing to a variety of other harms.

Gaming addiction was prevalent before GaaS/F2P but seems to have been exacerbated by it. This is because GaaS often uses variable rewards, daily push notifications, limited-time events, and “dailies” to encourage habitual and addictive play.

A 2018 meta-analysis estimated that 4.6% of adolescents met the criteria for Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD), including 6.8% of male adolescents. Later, a 2022 meta-analysis found that 8.8% of adolescents meet the criteria for IGD. The prevalence is even higher when broken down by sex: while the 2022 study did not provide combined estimates by both age and sex, it found that 15.4% of males overall meet the criteria for the disorder. Another study found that 19.2% of Chinese male adolescents met the criteria, compared to 7.8% of females.

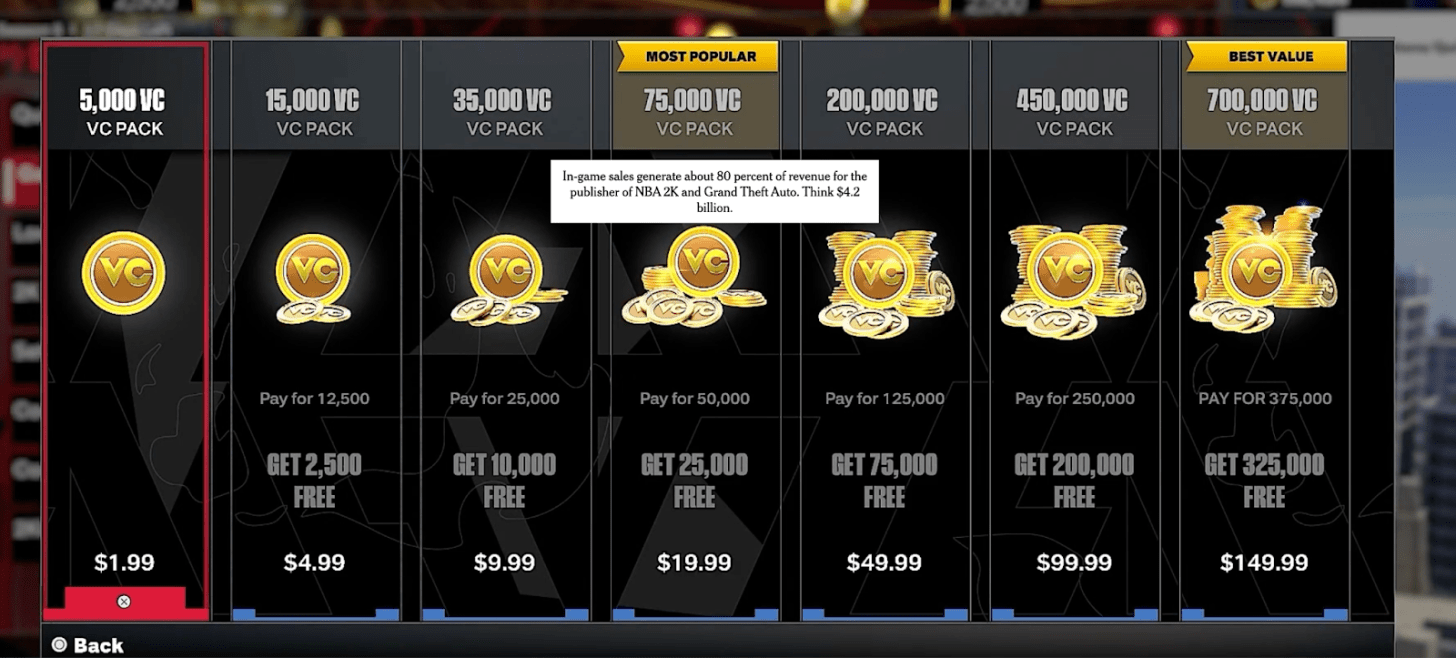

Most GaaS games use microtransactions, loot boxes, and/or in-game currency to encourage spending, leading to a variety of financial harms.

A 2024 investigation into one online game found that in-game expenditures are highly concentrated among some users, with 90% of revenue coming from 1.5% of players, what industry calls the “whales,” a term that comes directly from the casino business.

Modern GaaS games like Fortnite and Roblox often use gambling-like mechanics (e.g., ‘Loot boxes’ and ‘gacha’ systems) to encourage spending, especially among children. Over time, these techniques risk normalizing gambling behaviors for young players.

A 2018 survey of 2,865 adolescent gamers found that 13% had played gambling-style games online. One survey found that in 2019, 43.7% of eighth-grade boys purchased a loot box in the past year, which rose to 48.6% in 2022. In other words, half of 8th grade boys are gaining practice and familiarity with gambling.

Social features like open chats and anonymous interactions expose users to strangers, including those with malicious intent. Children are especially vulnerable to these risks.

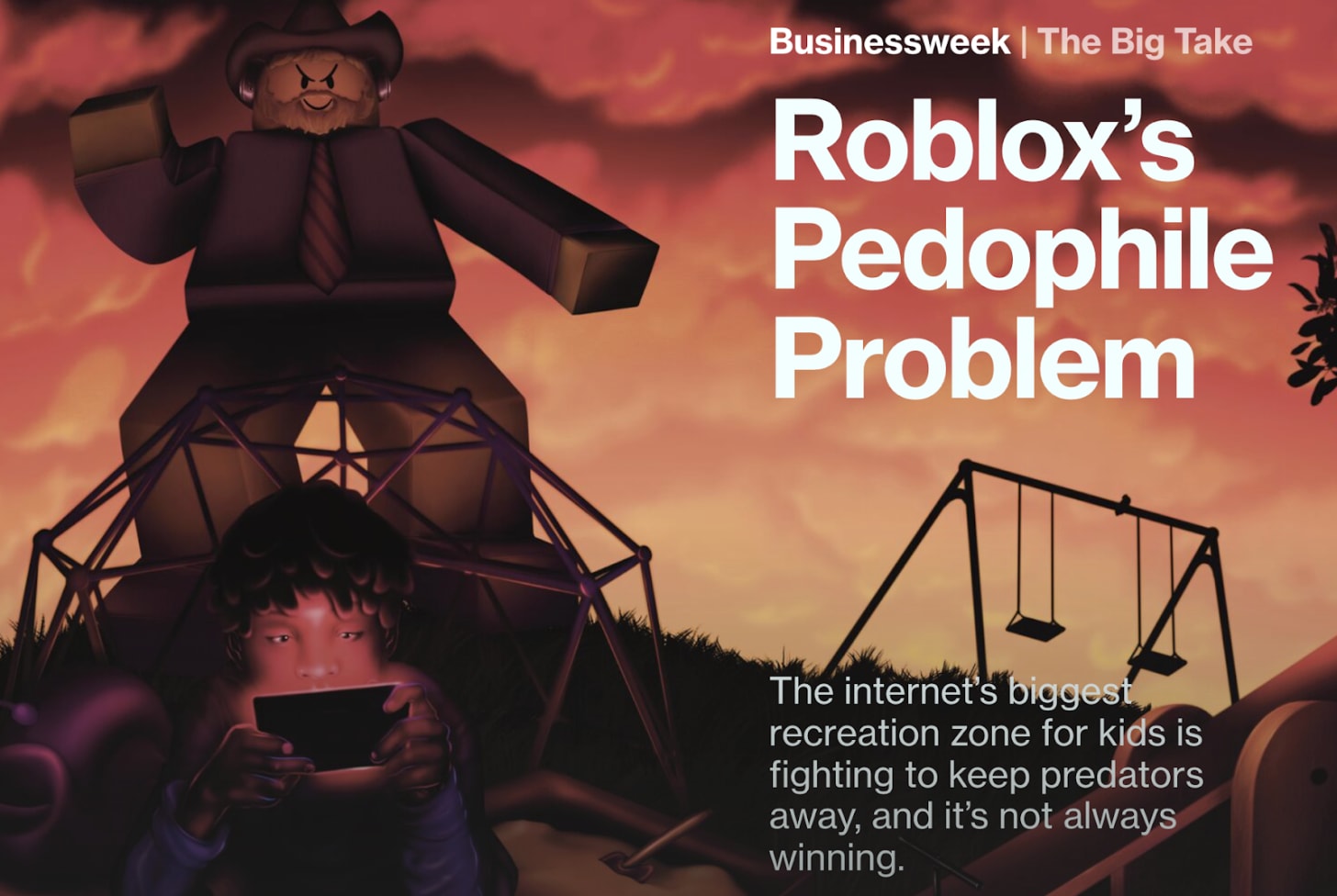

Ten percent of teen girls have been sent unwanted sexually explicit content while gaming. Various exposes have been published on the migration of predators to online games, such as one NYT article “Video Games and Online Chats are ‘Hunting Grounds’ for Sexual Predators.” In 2023, Roblox reported 13,316 instances of child exploitation on its platform and over 1,300 law enforcement requests related to such cases.

The rise of mass-scale user-generated content has brought unprecedented accessibility to extreme content. Content and ideologies that would have been highly unlikely to appear in mainstream games are now more likely to present on platforms actively used by young children.

Roblox has a poor track record with content moderation, in part because 70% of Roblox experiences are user-created. For example in the three month period of Q4 2023, “Roblox users generated and uploaded approximately 205 billion total pieces of content to the platform, and has 0.77 moderators per 100,000 users to moderate that content along with their automation systems. A 2023 multinational survey of adolescent gamers found that 51% of all gamers surveyed had come across extremist content (hate-based harassment or incitement to discrimination and violence) in online games.

In the example below, researchers from NYU found Nazi villages and ISIS propaganda on Roblox.

Heavy gaming is associated with elevated risks of depression. One study of 221,096 adolescents found a curvilinear relationship between gaming and mental health: light gaming (less than one hour per day) was not associated with harm while heavy gaming (five or more hours per day) was linked to a higher risk of depression. (risk began increasing after 1hr of use per day)

Heavy gaming is tied to problematic sleep outcomes, which in turn can contribute to negative impacts on sustained attention and academic performance. Forty-five percent of boys and 37% of girls who game report that video games hurt their sleep, and 21% of boys and 11% of girls report that it hurts how well they do in school. One systematic review of experimental studies found that heavy video game play, especially at night, can lead to insufficient and low quality sleep, with possible effects on cognition in the subsequent waking days.

On July 15, 2025, Bennett logged into one of our Roblox accounts registered as under-13 and checked out the popular game, “Public Bathroom Simulator,” which has had over 19.4 million visits and was rated ‘N/A’ for maturity, meaning any user can access it. In a single ten minute interaction, he witnessed predatory behavior, sex-like content, several pushes toward spending money, and an inappropriate chatroom.

Upon first entering the game, one may easily (or accidentally) click on the “Gamepasses” and “Item Shop” tabs, which are present throughout a user's play and offer a variety of items and passes with the use of Robux.

On another tab, a user can send a friend request to any of the over 1,000 users present in the game.

Within the bathroom, one can roll around and play with others in the bathtub.

Outside of the bathrooms are several beds upon which users can dance and write in the chat.

On a nearby bed (see image below), Bennett encountered a naked male avatar writing in the chat while laying on the bed, “want to play with me? Please, I’m bored.” One user responded, “kiss my ###.” Another said “u a school bus cause i can fill u up with kids.” The naked avatar then responded “looks like i got all the ladies here.”

In Adopt Me! — a game rated “All Ages” with over 40 billion visits — players are quickly encouraged to try on thousands of outfits, many sold by other users for Robux. The core gameplay begins with a mysterious egg, which can be hatched into a pet by logging in daily, caring for the egg, and spending earned or purchased currency on the egg’s needs. However, players willing to spend real currency on Robux can bypass this process entirely using the “Instant Hatch” option, costing about 45 Robux (about $0.50 USD).

The pet, a randomized reward, is revealed with bursts of color and sound, with the most coveted outcome being a rare “legendary” pet, reportedly with a 4% chance of appearing. In effect, the egg functions like a slot machine: the outcome is unknown until after payment, whether through time or real money, and there’s no limit to how many eggs a player can hatch (only how much they’re willing to spend).

It’s important to recognize that the three major platforms mentioned in this post — Minecraft, Fornite, and Roblox — each pose their own distinct risks and benefits. They should not be treated as equally harmful.

Minecraft, which requires an upfront purchase, offers the most safeguards of the three. It avoids “pay-to-win” mechanics and allows players to opt out of in-game purchases entirely through its Java Edition. Parents can also choose fully offline play. Still, the game’s endless progression, social appeal, and creative freedom make it difficult for many children to stop playing.

Fortnite removed loot boxes in 2019 following legal pressure and public criticism. CEO Tim Sweeney later called them “akin to slot-machine gambling” and “hostile to players,” arguing that users should know what they’re paying for. While chat and user-generated content still pose risks, the moderation process is more robust than on other platforms. However, as a free-to-play game, Fortnite remains heavily monetized. Success often depends on purchasing weapon upgrades, skins, and battle passes, making ongoing spending feel necessary. The game’s innumerable IP collaborations — paired with reward loops like daily quests, timed events, and battle passes — create a cycle of anticipation and gratification that makes the game especially addictive.

Roblox, in our direct experience and through the available evidence, presented the greatest concentration of harmful content, inappropriate interactions, and manipulative monetization. Even after registering as minors, we encountered crude, sexual, and violent material — often without even looking for it. Of the three games, Roblox is the most popular platform for children, and is also the one most resembling the unregulated “amusement park” described in our introduction. In its current form, we do not believe Roblox is a safe environment for children.

Underlying these three platforms, and nearly all GaaS titles, is an incentive structure designed to maximize how much time and money children spend. In this new business model, as a game becomes more popular and more engaging, it doesn't just attract new players — it increases how much each user spends (with their attention, and their parents credit card). The more immersed players become, the more likely they are to spend, driven by social pressures and the desire to succeed..

The bottom line: Chats, skins, premium subscriptions, battle passes, intermittent rewards, and other features which exist across platforms exist to serve two core purposes: keep kids playing and keep them spending.

It does appear that there are several benefits to gaming. There are studies showing that games like Minecraft are well-liked by teachers. We found several fun and educational games on Roblox. Some research suggests that moderate gaming may help certain players during hard times, such as the isolation of the COVID pandemic. Light use of most games does not appear to increase risks of depression, and some gaming appears to improve certain cognitive skills.

But most of this research was done on games that used the old business model. With the new business model comes a new set of risks that have not yet been well-studied. Especially with a model designed to extract as much time, attention, and money from users as possible, the likelihood of harm is probably higher today than it was five or ten years ago.

This business model doesn’t just want gamers, it wants heavy gamers. It wants to find or create whales. And it’s working. Heavy gaming among children and teens is on the rise, and they are facing real risks such as developing problematic or addictive game use, experiencing depression or anxiety, obesity, and falling behind in school.

This business model is also incentivized to make it easy for kids to bypass any age verification system. Most popular online games, including on the child versions of the games, have zero age or identity verification — besides requiring a manually entered birthdate. (Note that we were able to create multiple fake accounts, for users of various ages, without ever undergoing any kind of age verification other than entering new birthdates).

Game companies know about these problems, yet they try to push their users to whatever will make them the most profit regardless of the risks to the users. For example, EA’s FIFA game monetizes users with FIFA Ultimate Team (FUT) mode which incentivizes users to spend on FUT packs to build the best soccer team. In a leaked internal presentation 2021 from EA, owner of FIFA, it stated the following:

“Players will be actively messaged + incentivized to convert throughout the summer. FUT is the cornerstone and we are doing everything we can to drive players there.”

Many developers understand the problems too. That’s why some of them don’t let their own children play the games they help create. As one explained in a New York Times op-ed titled I Make Video Games. I Won’t Let My Daughters Play Them, the concern is real. The author said that in regards to his own children,

Thinking about my games in my daughters’ hands, I had to confront what these products really were and what they could do. Knowing all the techniques with which we tried to bring about addiction, I realized I didn’t want my children exposed to that risk.

Even employees inside major gaming companies are speaking up. In one lawsuit filed against Roblox, one Roblox employee was quoted saying:

You’re supposed to make sure that your users are safe but the downside to that, if you’re limiting user engagement, it’s hurting our metrics. It’s hurting our active users, the time spent on the platform, and in a lot of cases leadership doesn’t want that.

Few parents would ever allow their children to spend hours everyday in an amusement park full of unvetted rides designed by random people (including children), hidden charges engineered to extract money, and anonymous adults pretending to be children. Yet this is precisely the experience that many online games have introduced into the schools, bedrooms, and pockets of millions of children.

We are not telling parents to say no to video games. We are instead warning parents about this specific kind of unregulated online universe that is designed to endlessly squeeze time, attention, and money out of their users.

Video games remain a potent medium for connection and play — some of Bennett’s fondest memories were spent with friends and family around a Nintendo Gamecube playing Super Smash Brother’s: Melee.

But today, the same technology that connects families and lifelong friends across state lines is also designed in ways that makes it easy (and safe) for predators to contact children. The same tools that offer spaces for them to explore, compete, and challenge themselves in ways that the real-world often no longer allows for also addicts and exploits children.

It does not need to be like this. We can imagine a better and safer online world.

In the early 1960s, auto manufacturers created beautiful, exciting cars that were “unsafe at any speed,” as Ralph Nader showed. The companies saw expenditures on safety as unprofitable. But Nader’s advocacy initiated reforms that led to crash testing and the publication of clear rankings of safer versus more deadly car models. A 2021 report from the Center for Study of Responsive Law, reflecting on the impact of Nader’s book and the industry-wide effects of safety testing, noted: “The publishing of [crash test] results… caused automakers to compete on safety for the first time and to acknowledge that ‘safety sells.’”

Right now, as video games have evolved into GaaS ecosystems that put children into intense interaction with anonymous strangers, the companies seem to see safety as a hindrance to profitability. That has to change.

Where might that start?

For parents, who do not have the luxury to wait for change, the single most important thing you can do is to delay smartphones until age 14, which prevents 24/7 access to addictive-by-design games. The second is to keep games out of the bedroom, which can help protect sleep and help mitigate the risk of unwanted and inappropriate conversations with strangers. Third, we recommend that parents play any game they are considering giving their child access to for a few days to understand the risks. Finally, when deciding which games to allow, consider the business model. Consider choosing games with clear, upfront pricing — where you pay once, rather than games designed for continuous spending. Because this is a collective action problem — where any kid who is not playing these games risks being left out, try to find like-minded parents of your kids' friends to do the same.

From a policy perspective, the most important single feature, we believe, is that any platform used by children should have “Know Your Customer” rules, as we have for banking, insurance, and prescription drug sales online. A company conducting business in these areas cannot just serve any anonymous person; they must know whom they are dealing with.

If a gaming company voluntarily adopted reliable identity verification procedures, including age verification, it would immediately eliminate most of the sextortionists, groomers, and other bad actors. It would allow companies to truly enact varying protections for users of varying ages. This would also pave the way to setting safety standards to default for under 13 accounts: no in-game chat, invisible profiles, and maximum content filtration.

Our hope is that, someday soon, gaming companies will compete on safety. Until then we are handing over our children to amusement parks that seem to be free, but that are extracting a hidden price few parents would knowingly pay.

.png)

![Patrick Soon-Shiong Taking LA Times Public [video]](https://www.youtube.com/img/desktop/supported_browsers/chrome.png)