Jun 04, 2025

I’m exhausted. Worn down from dealing with the medical system that is supposed to heal us. It shouldn’t be this way and we have the technological means to fix at least some of it right now.

Last Sunday, as I prepared to preach at my church, my mom fell unconscious for reasons we still don’t understand. To my non-medically trained eyes, it appeared she was having a stroke or seizure. I’ve seen both firsthand and immediately felt the crashing wave of fear paired with a determination to get help. Fast.

The church family was amazing at moving into gear, as were the emergency medics who soon arrived. We were moving. Then we got to the hospital and started days of testing, each test — thankfully — coming back clear of the tell-tale markers for stroke or seizure.

When a loved one has a medical emergency, the worry over both the known and a multitude of unknowns take their toll on us. They should.

Even in the best scenarios, clearing the initial fog of the emergency takes time. Tests have to be processed and analyzed. The uncertainty when, as in Mom’s case, no clear diagnosis comes back only rolls in new waves of fog.

Some uncertainty was understandable and unavoidable: tests didn’t reveal obvious problems and so doctors understandably had to keep searching. But not all the uncertainty was necessary.

If we’re walking these halls, chances are, we’re worried about what’s happening to someone we love. (Credit: Timothy R. Butler)

If we’re walking these halls, chances are, we’re worried about what’s happening to someone we love. (Credit: Timothy R. Butler)

Question marks we solved with technology in other areas of life somehow remain tolerated in medicine. As hours slogged towards days dotted by tests at unpredictable intervals, the ill-defined plan started to wear on the whole family.

When would the next examination happen? How was lab work processing progressing? When would we ever get to talk to a doctor who could explain what happened or what needed to happen next?

In the ER waiting area that Sunday night, my dad and I took turns dutifully stopping at the information desk every fifteen minutes or so, asking if we could go back yet. “No,” came the answer repeatedly. After what felt like an eternity, on my final stop at the desk, the receptionist responded in surprise, “Oh, yeah, she’s awake and been ready for a while.”

I didn’t say it, but I sure thought ”thanks for letting me know.”

So it continued: from a week ago Monday until my mom was discharged midweek, we were promised meetings with a neurologist. They never happened. Either they were never scheduled or the doctor never showed up, but since we had no idea of the when, we could only keep hoping and asking.

I certainly was appreciative of the doctors’ thoroughness, even as Mom came to and returned to a normal, albeit tired and sore, version of herself. I didn’t want them to release her prematurely only to have something more permanently devastating happen. Being thorough shouldn’t be a reason for leaving the patient and family with no idea what the plan is, though.

Even discharge itself was a variation on the same theme. The house doctor said my mom was ready to go at 8:30 a.m., but forgot to turn in the paperwork. Five hours — and plenty of nagging on our part — elapsed before the nurses tracked down the doctor and got the green light to remove the final IVs and prepare prescriptions.

Did our pushing help the process along faster than it would have otherwise? I don’t know. There’s no way to tell because everything remained so vague until the minute they wheeled Mom outside. All we knew is she was supposed to go home and we wanted her to get there so she could finally get some genuine rest and healing could begin.

If you or yours have dealt with hospitals recently enough not to have repressed the memory, all of this likely sounds eerily familiar. Hospitals flub communication constantly, only making the road to recovery harder. A recent study found a link between poor hospital communication and worsened outcomes.

It doesn’t need to be this way. If the medical system had the will, we already have the technological means right in front of us.

Consider: I can tell each step of the delicate operation going on… when I order a pizza. Why can I tell if Joe is assembling my pizza or MacKenzie is boxing it, but I can’t tell if a loved one is going to get a CT scan in an hour or if it has been pushed to tomorrow?

![]() Sites like Amazon outline clear steps in the delivery process, noting what has happened and what is to come so we feel “in the loop.” (Credit: Timothy R. Butler)

Sites like Amazon outline clear steps in the delivery process, noting what has happened and what is to come so we feel “in the loop.” (Credit: Timothy R. Butler)

Detailed tracking is ubiquitous today. I order a package from Amazon and I know how many stops are between the delivery truck and my porch. DoorDash goes further and lets you watch the delivery vehicle’s location on a map alongside the ETA.

Medical professionals might argue they don’t have time to keep patients and family members up-to-date on when tests will occur or doctors can talk. But, the Amazon and DoorDash drivers don’t have time to text me updates, either. My ability to receive those updates is a byproduct of information they do need to record.

Modern organizations record enormous amounts of data for auditing, supervision and the like. Companies like Amazon double dip into their internal data needed for tracking successful deliveries and assessing operational efficiency, turning that treasure trove into a way of pleasing customers almost “for free.”

This could easily be applied at hospitals. Most of the medical staff that would come into my mom’s room would scan her patient information bracelet or use the in-room computer as part of their duties. The hospital almost certainly records who accesses those records and where they did.

Such logs could make it possible to track progress towards when the doctor is going to walk in or Mom was going to be wheeled to the imaging lab. Overworked doctors and nurses wouldn’t need to put in a single bit of additional effort.

The information is already there. Why not share it?

Raw logs would be useless to patients, but the simplest algorithm could use past and present data to accurately estimate how long a nurse or lab trip was away from a given patient. Why not reveal that to the patient on an in-room daily itinerary screen?

Even my license bureau — we know how concerned those places are with our well being — does that much on big screens in the waiting area now. If the DMV can make a small nod to caring for customers, a place allegedly focused on healing surely could too.

Anything that lowers stress even a jot by making the upended world one experiences in a hospital more stable would be a gain. Let patients focus on healing rather than worrying.

Likewise the patient’s families. Many people come home needing substantial care, but time a caregiver should be resting and preparing ahead of discharge is often spent instead in institutional halls, hoping for a chance encounter with a doctor who can provide an update.

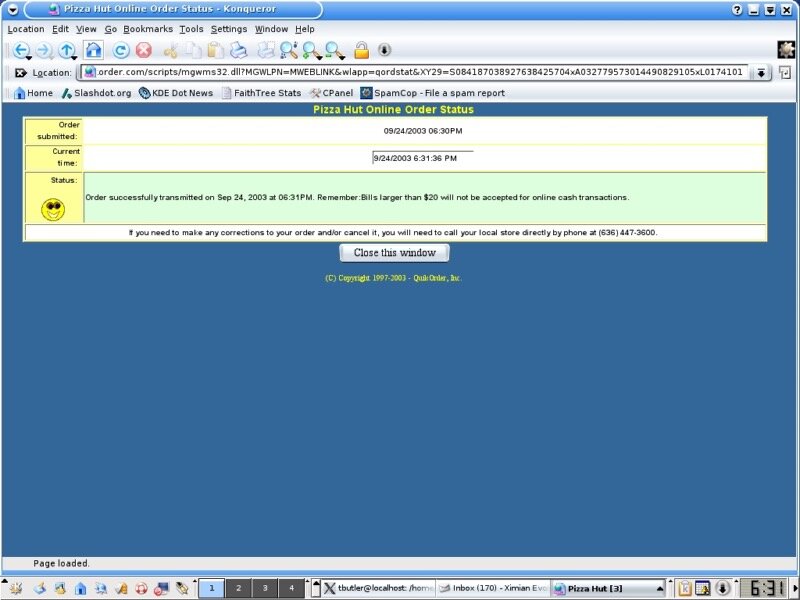

It has been a quarter century since the first time Pizza Hut told me to get my tastebuds ready for dinner. A notification letting me know the estimated ETA for the doctor stopping by my mom’s room soon wouldn’t have seemed out of place — it’s absence does.

This screenshot looks old because it is. Here is a pizza I was able to successfully track twenty two years ago. Yes, it turned out delicious. (Credit: Timothy R. Butler)

This screenshot looks old because it is. Here is a pizza I was able to successfully track twenty two years ago. Yes, it turned out delicious. (Credit: Timothy R. Butler)

We have the means, the hospitals have the resources to implement it and everyone would benefit. Even the hospitals would benefit, as frazzled staff got relief from folks like me asking for updates. That same study on communication even found improving communication lowered medical providers’ risk of malpractice suits.

If dinner and SD cards are worth notifications, we’re well past the time for updates on whether Mom had a stroke or not. That I even need to say this is unacceptable.

We know how to do precision tracking. It’s time to deliver it for matters of life and death, not just takeout.

.png)