The animals that plummeted 85 feet into Wyoming’s Natural Trap Cave provide a layered history of life dating back to the Pleistocene

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/adsheadshotcolor-edit.png)

Ari Daniel - Host, "There's More to That"

June 12, 2025

Natural Trap Cave is a pit in northern Wyoming into which countless animals have fallen and met their untimely demise since the Pleistocene. Paleontologists today find the cave a treasure trove — a stunning record of the species that have long roamed the area. The mammalian fossils left behind shed light on the climate, food sources and migration patterns of these species from earlier eras.

Careful excavation work over the years that has involved sifting for bones, extracting ancient DNA, and looking for prehistoric pollen has revealed not just the plants and animals that once populated this part of the world, but also the ecosystems and climates that governed it. It also has required some rather advanced rappelling skills.

In this episode, host Ari Daniel speaks with vertebrate paleontologist Julie Meachen and Smithsonian contributing writer Michael Ray Taylor about what rappelling into Natural Trap Cave reveals about its contents and what it can tell us about Earth’s past.

A transcript is below. To subscribe to "There’s More to That," and to listen to past episodes about the sex lives of dinosaurs, the numerous archaeological treasures that await beneath the city of Rome, and the science of roadkill, find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, iHeartRadio or wherever you get your podcasts.

Julie Meachen: I never was a dinosaur kid.

Ari Daniel: This is Julie Meachen.

Meachen: Like, I was never that kid who was obsessed with dinosaurs. I always liked mammals better. Like, I was always a fuzzy mammal person.

Daniel: Growing up, Julie always imagined she’d be a veterinarian. These days, she does work with cats and dogs, but mostly the ones that live near the end of the Pleistocene.

Meachen: Saber-toothed cats, the dire wolf, and believe it or not, coyotes. Those are the ones that I do a lot of work on.

Daniel: Julie is now a professor of anatomy at Des Moines University.

Meachen: I’m also a vertebrate paleontologist and I mostly focus on large mammalian carnivores. Carnivores are near and dear to my heart.

Daniel: For the past nine years, she’s spent a lot of time deep underground in a prehistoric cave near the border of Wyoming and Montana.

Meachen: So basically, this pit is a sinkhole and likely in the hundreds of millions of years is when this cave formed.

Daniel: It’s called the Natural Trap Cave. It has that name for good reason, which we’ll get to in a moment. Tell me about what it’s like to be down in there.

Meachen: Absolutely. So we get into the cave by rappelling. We work with a really wonderful team of cavers that help us set up all the ropes and do all the safety protocols and everything. So they rig up the rope system for us and then we harness up. And then this is kind of the scariest part, and when I first started doing it, this was what really intimidated me. It’s really light up top and it’s dark in the cave compared to upside, it’s kind of hard to see. So the next thing you’ve got to do after you get rigged up on your rope is you actually have to turn around backwards, get onto the ledge to prepare to rappel backwards down into the cave. So you’re basically like walking backwards into the abyss is kind of what it feels like when you’re ready to go into the cave.

Daniel: Whoa.

Meachen: So you’ve got to just kind of have a, not a leap, you don’t want to jump off the ledge, you just kind of have a step of faith backwards, and so you just step backwards off the ledge…

Daniel: Into nothingness.

Meachen: Yeah, into nothing. And so when you get down there, you’re like, “Whoa.” It’s a big open cavern. It’s actually very well-lit and it’s very cool and it’s very damp in the cave. And you definitely want to have a set of winter clothes or coveralls, padded coveralls is what I bring down there. And so you take off your climbing gear and you make sure that you keep your helmet on at all times and then you can just work.

Daniel: Julie’s been willing to rappel into that abyss year after year because waiting for her at the bottom of that pit is a treasure trove of bones. For the first few hundred thousand years of this cave’s existence, anything that fell in over the side never made it back out again.

Meachen: The cave opening, which is about 20 feet by 20 feet in diameter, something like that, is at the bottom of this little hill, so you can’t see the opening when you’re running. And I imagine that most of the animals that are found in the cave were running either away from predators or running to catch prey and they didn’t see the hole.

Daniel: Wow.

Meachen: And so they went over this little ridge and then bloop, in they went into the cave and they fell 85 feet to their death. And the reason that they have been so well-preserved is because of the temperature in the cave. The cave never gets above 42 degrees Fahrenheit.

Daniel: So it’s kind of like a refrigerator?

Meachen: Yeah, it is kind of like a refrigerator. There’s no wind, there’s no weathering. Stable weather conditions inside the cave preserve the animals, preserve their bones, I should say.

Daniel: So what can hundreds of thousands of years of animal bones stacked atop one another in this evolutionary layer cake tell us about life on Earth? Julie’s determined to find out. From Smithsonian magazine and PRX Productions, this is “There’s More to That,” the show that plunges beneath the surface in search of a good story. In this episode, the mysteries contained within the Natural Trap Cave. Stay tuned.

Daniel: I am wondering, what has your experience been like writing and reporting on caves generally?

Michael Ray Taylor: I’ve written about many things in the last 40 years, but I always come back to caves because it’s something I love and have been fascinated with really since I was a small child.

Daniel: Michael Ray Taylor reported on Natural Trap Cave for Smithsonian magazine.

Taylor: I started caving when I was an undergraduate student long ago at Florida State University. I joined a student caving club and almost immediately, I was writing about the trips we took for the club newsletter. I wound up going to graduate school in a creative writing program, and the thing everyone hammers into you is write what you know. Well, caves are what I know.

Daniel: Yeah. What did you find magical about them?

Taylor: Well, caves are a very delicate environment. I’ve left my footprints in very remote caves that I’m sure my footprints will be there for thousands of years to come. In fact, I’m involved in mapping a cave in Tennessee right now where there are Native American footprints that were made over 3,000 years ago.

Daniel: Wow.

Taylor: And if we step on them, are gone, so we’re very careful. But the formations in the caves, a single human touch can destroy them. And the creatures that live in the cave, they are adapted to this unusual environment. So what happens if you become a caver is you become passionate about conservation.

Daniel: Michael actually visited Natural Trap Cave in the late ’80s. At the time, the site was gated and locked, but he could still peer inside.

Taylor: And I thought, “Gee, it would be fun to go in there sometime with paleontologists.”

Daniel: Then, two years ago, Michael was at a national caving convention in South Dakota, which he attends every summer.

Taylor: There’s a big campground where half the people attending the convention camp out.

Daniel: Oh, amazing.

Taylor: And every Wednesday night, I’m in an all-caver rock band that plays the convention.

Daniel: You’re in a rock band that plays at the convention?

Taylor: Yeah, I play bass guitar. There’s this band that was started by a geologist from Tennessee called The Terminal Syphons, which is a caving term for a flooded passage. And they’ve been playing the NSS convention since about 1986, I think. I joined the band in ’91. I don’t play every year, but most years I play with them.

Daniel: At some point offstage, Michael met a member of Julie Meachen’s research team.

Taylor: He pulled me aside and said, “Mike, you really got to come out and write about this work Julie’s doing in Natural Trap.” And he described it and I thought, “Yeah, that sounds exciting.”

Daniel: Last year, he made it to the cave.

Taylor: I’m not 20 years old anymore. I don’t do gigantic pits in Mexico like I used to do, but I can still more or less handle the 85-foot drop into Natural Trap. And that’s what I did. So I could just look over the shoulders of various scientists and graduate students and even a couple of undergraduates as they were pulling out all of this history of paleontology. What you get is a gigantic pile of bones mixed with soil that washes in from occasional floods, ash that comes in from volcanic eruptions. In fact, the oldest soil layer in the cave was dated to an eruption about 151,000 years ago. So Julie has become the master of this realm inside the cave and inside this enormous pile of bones.

It was a lucky accident of geography and geology that this hole persisted for so many thousands of years in the same spot. And it’s more than just a trap that animals would fall into, but it happens to be located at a migration crossroads. It’s near the southern end of what was once an ice-free corridor that stretched all the way from southern Montana into Alaska and across to Asia when the sea levels were lower because of the great glaciers. So during periods when this corridor is open, vast migrations of animals from Asia coming to North America would pass through. Horses and camels are native to North America, but the reason we know about horses and camels today is some that passed through that corridor wound up in Asia and spread to Europe. And likewise, some Asian animals, such as the ancestors of the mammoth, came walking through and lived in the Americas for thousands of years.

The late Pleistocene was a period of, for any one animal, things were as they had always been. But in fact, the climate was rapidly changing. There were these cycles of glaciation and then the retreat of glaciers and then more glaciation and the retreat of them. And this affected the plants, the animals, all of the life in this area, which luckily this cave is sort of right at a crossroads of these intersecting changes. And so by looking at the bits of evidence that come out of the cave and comparing it to what’s been done from excavations in other places like Alaska and Siberia, it paints a much more comprehensive picture of what life was like then. And what were some of the stressors placed on animals as the climate became drier and warmer or wetter and more lush, both of those things happened in repeated cycles. It’s like a roadmap to exploring the late Pleistocene, all made possible because it’s been such a stable environment throughout all of those changes.

Daniel: Humans started descending into Natural Trap Cave in the 1960s when developments in climbing technology first made it possible.

Taylor: There was an explosion of what we call vertical caving that is going into caves on ropes because some new devices had been invented that made it easier to rappel into and climb out of a cave in what we call a free drop, where there are no walls around you that you can touch. So you’re just hanging on a rope until you hit bottom, and sometimes that’s hundreds of feet down.

Daniel: Wow.

Taylor: And so it was only natural that this cave, which is visible from space, you can —

Daniel: Really?

Taylor: — see the entrance easily on Google Maps, it’s a nice big hole that cavers became curious about it. And very quickly, they noticed in some places you could see bones on the big giant cone of soil at the bottom. It’s not just stacked bones like you would see in a boneyard, it looks like a big pile of dirt. But as you look closer, you can see little bits of bone poking out here and there.

And so the Bureau of Land Management, which owns the land, recognized that this was scientifically important. And they also recognized that it was dangerous. And for those two reasons, they commissioned a big gate to be placed over the entrance, which was installed in I think 1971 and 1972. It finished in ’72. And so it’s this huge steel grate. It’s got bars in it that are wide enough for birds to fly in and out, bats to fly in and out. Small animals still fall through but large animals and people don’t fall through anymore. And this grate is 20 feet on one side by 16 on another, something like that.

Daniel: Tell me about the history of the work in Natural Trap Cave. I understand there’s been some stops and starts?

Taylor: Yes. Well, I’m sure the Crow and other Native tribes were aware of the cave for thousands of years and were wise enough to stay away from it. No human remains have ever been found in the cave. But the first person to go into it scientifically, and this was back in 1971, was an archaeologist and his name was Lawrence Loendorf. And Lawrence Loendorf was interested in finding human artifacts or remains. He didn’t find any. He found one knife, which was probably a Native American knife that was dropped in and one piece of worked wood, it was in a pack rat nest. But he noticed that there were lots of animal remains in the cave, and he invited a paleontologist who was also a caver named Carol Jo Rushin. She was the first paleontologist to go into the cave in ’72, and that started a major excavation.

For a while they built this huge metal scaffold all the way from the entrance to the floor so you could walk in and out. But there were some safety issues with the scaffold. And also as they did more excavation, they realized the only thing holding the scaffold up was the various soil they were trying to excavate. And so after a few years, that was removed and they started doing what we do now, which is just using ropes to get in and out of the cave. And that excavation continued until the 1980s and it was shut down by BLM —

Daniel: That’s the Bureau of Land Management.

Taylor: They had done all they could do with the techniques available then. Genetic testing was just becoming possible on a large scale, and there were other types of new tests being developed that use isotopes and other things to date paleontological remains. The BLM, I think in association with the Park Service has had some involvement with it over the years. They both said, “Let’s wait a while, and when the right proposal comes along, we’ll reopen excavation.” And Julie Meachen was the one who had the right proposal. And she put together a team of about 20 different scientists with different specialties. And I think because of the interdisciplinary approach they’re taking, they’re getting a more holistic understanding of the history that is preserved almost like a museum in this wonderful cave system.

Daniel: What was it like once you actually got into the cave?

Taylor: Caves have a unique smell. The only thing I’ve ever been able to compare it to is the smell of your garden if you’re out digging in the dirt. And really what that is, is the smell of actinomycetes and other fungi that live within the soil of the cave anywhere in the world practically. But I find it relaxing. It’s not like the surface. It’s a little dirty. You expect to get some mud on you here and there, especially those who are doing the digging and excavation. They’re lying on their belly a lot of the times with dental instruments and paintbrushes cleaning off one piece of bone so they can pull it out and get the next piece of bone that goes with it.

Daniel: Such detailed work.

Taylor: When I was in the cave, the first person I came across, her name was Megan Hormell. Megan was removing a bighorn sheep scapula, it was a big shiny plate of bone, but there were other pieces of what appeared to be the same sheep right around it. It looked like the sheep had been chased in and had fallen. Most of it had landed in the same spot and stayed there. It was in a layer of soil that’s about 23,000 years old, so it had fallen 23,000 years ago. And she was working on some vertebrae next to the scapula and what she thought were neural fibers that sometimes are preserved in the soil, and she wanted to try to get those out.

And Julie was giving her advice on what to do with that. Julie, throughout the day, walks around and checks on everybody and comments on what they have, and periodically someone will find a fresh bone and walk up to her and say, “Is this something?” And she might say, “Yes, that looks like a bit of dire wolf.” Or she might say, “No, that’s a modern pack rat,” and she’s so expert at this, she can tell at a glance.

Meachen: My personal projects include things like the morphology of the wolves down in the caves. We do have some dire wolves, but most of the wolves that are in natural trap are a wolf called the Beringian wolf, which is an extinct subspecies of the gray wolf. And so looking at how those wolves have moved through time, where they came from, what their genetics tell us, what their morphology tells us, that’s one of my projects specifically, but I am highly collaborative on all of the other projects.

Daniel: Do some bones give you more information than others?

Meachen: Yeah, sometimes. Some are just fragmentary and they can’t tell you much, and those ones we still collect anyway, but they’re not as exciting. The thing that I really love to get out of this cave is ancient DNA. And we found some really amazing results from the DNA of animals that have been down there.

Daniel: This is ancient DNA from the bones?

Meachen: Mm-hmm, yes.

Daniel: Ancient DNA refers to DNA recovered from rather old specimens. And it’s typically fragmented and poorly preserved, so researchers have to use special techniques to determine the organism that left it behind.

Meachen: My favorite bone to find is the inner bone or the petrosal. Basically, it has the cochlea in it and it has the semicircular canals. The bone is really, really hard. It’s one of the hardest bones in the vertebrate body, and so it doesn’t get replaced as fast by minerals as other bones do. It does keep that integrity. And since it has all that goo inside from the semicircular canals and the cochlea, there’s a higher percent chance that DNA will actually be preserved in that bone. So that bone is really fascinating to find because I always know that we can get some good DNA out of those bones. Using ancient DNA, you can create a phylogeny of where they fit in the family trees compared to closely related species or even other individuals of the same species that you might already have DNA for. You can also use their DNA to figure out their effective population size and how much genetic variation there probably was in the population of that species.

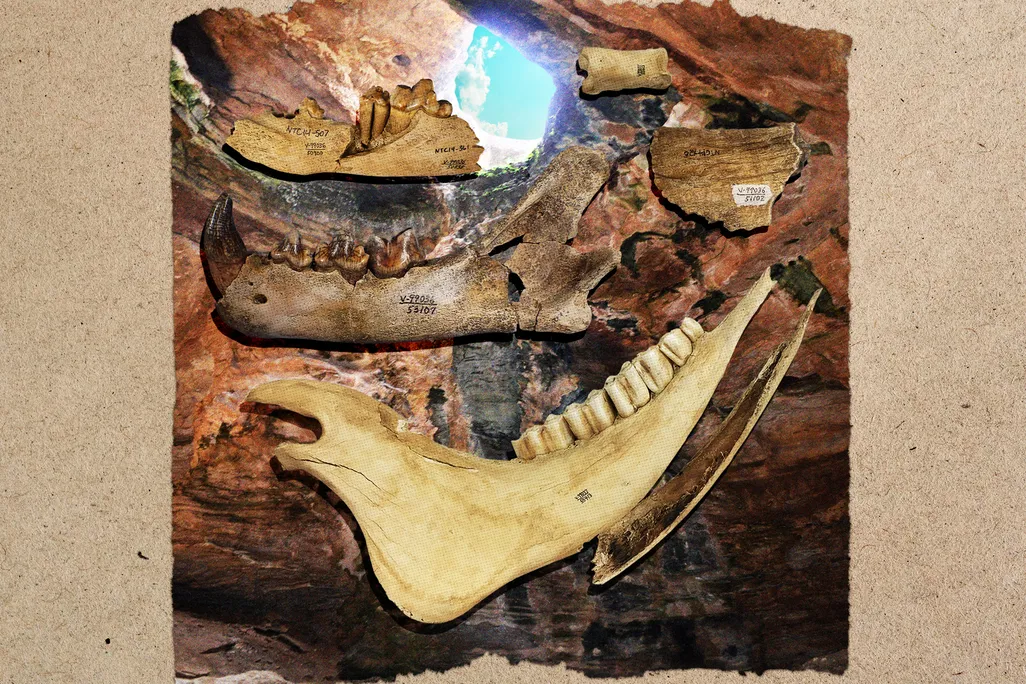

Daniel: Different parts of an animal’s skeleton can yield different kinds of scientific discoveries. Take teeth, for instance.

Meachen: Teeth can tell us a lot. It can tell us what kinds of foods they were eating, whether they be plants or meat. The teeth are different shapes depending upon whether an herbivore was eating a browse diet, which would be like leaves or shrubs, or a graze diet, which would be more like grass. And additionally, the chemicals that make up their teeth, what we would call stable isotopes, can actually tell us about their diets more, what kinds of foods they were eating and the kinds of waters they were drinking.

Daniel: Really?

Meachen: Yes. The first year that we excavated in 2014, we found a jaw of an American cheetah, which was incredibly exciting. And then very close to that, we found the upper tooth area of an American lion. And so that was probably one of my favorite finds. That was incredible.

Daniel: When you’ve got such a giant pile of bones and fossils from all these different animals, how do you go about looking for them? Are they kind of stacked in a timeline almost from oldest to newest, or how should I understand this pile?

Meachen: There is stratigraphy, so there is sort of layers of older sediments below younger sediments, so it does go age-wise. So we do have some kind of way to distinguish ages in the cave. It’s not as beautifully laid out as we would like, and there are some missing time periods, unfortunately. But they do generally go from older to younger. And we have a couple of areas that we’re concentrating on right now.

So the main pit that was right under the drop zone was excavated heavily from 1973 to 1985. And they excavated this nine-foot-deep giant square, and then nobody really shored up the walls of that square or anything, so a lot of backfill fell in in the intervening 30 years between when they left and when I came in. So we don’t dig there in the middle anymore. It would just be too hard to get down to the fossiliferous layers again. So we kind of went out to the sides, digging laterally rather than straight down, and we found that there are a lot of bones laterally as well, especially in the southwestern direction. We’ve been taking that down slowly and finding lots and lots of bones.

Daniel: It’s not just bones, though. The Trap Cave is a repository for all kinds of organic material, including ancient pollen.

Meachen: Using the pollen, we can actually create a floral map of what was there. When we have pine trees, we have sagebrush, we have plants in the family Asteraceae, which is the daisy family. But basically we can see how the abundance has changed through time. And using that floral data, we can tell how wet it was, how cold it was, because those plants have very specific tolerance levels that they like. We can use that in conjunction with these bacterial branched chains that we get from the dirt. So basically, there are these bacteria that live in the dirt that give off these chemicals, which we can recreate the climate from these different dirt layers.

And so we are going to use those two things together to try to make a climate map of the site and then look at the animals that were there during that time and look at their different tissues, their isotopes, their size, their shape to figure out if we can have a one-to-one correlation of what the animals look like during periods of dry time and during periods of wetter time. We’re not a hundred percent sure the animals line up perfectly with the climate record, but that’s what we’re trying to find out. And we’re trying to find out which traits best reflect that climate record.

Daniel: You’re there obviously to study and learn and picture this period from the past, but is there any emotional quality to it? I mean, you’re there inside this giant prehistoric graveyard of all these deceased animals that have made a fatal mistake and landed there.

Meachen: Yeah, there is. I have a lot of empathy for these poor animals. I imagine them falling to their death. It makes me sad. I’m really excited to find their bones again. So basically, their awful demise is now a sense of joy for the people that are down there digging up the bones. And we do get really excited when we find something new. Every find is interesting, and every find kind of inspires joy and wonder. And if you find something rare, you get really excited. For example, we did find one vertebra from a mammoth this last year and those are super rare, super rare. As you can imagine, mammoths don’t run a lot and they probably don’t make the misstep of falling in very frequently. It was a juvenile mammoth that we found. And this poor thing fell in and fell to its death. And its mother probably was beside itself if she was not also in there with it. But now we get to excavate their body and it is exciting. It’s an exciting prospect.

Daniel: Julie has a bittersweet transition coming up. This will be her last season leading the excavation of the Natural Trap Cave.

Meachen: It’s a lot of work, but I will be passing it off to a junior colleague who is very enthusiastic about leading future excavations, and I will still come out into the field. I just won’t have to be the big boss who’s there the whole time from now on, which will be much nicer for me. After leading a field season like this for nine years, I would love to just be a participant on somebody else’s field season.

Daniel: Sure. Thank you so much. Thank you for your time. This was really fascinating, just imagining this place and the conditions that created it, that created such an archive of life for you to dig up years later.

Meachen: I know, it’s pretty amazing. It is a pretty amazing site. And I feel very privileged to be able to work at it for so long.

Daniel: I can tell. Thank you, Julie.

Meachen: Thanks.

Daniel: To read Michael Ray Taylor’s reporting about the Natural Trap Cave and see some photos, head to smithsonianmag.com. We’ll put a link in our show notes.

If you like the show, please consider leaving us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, the iHeart radio app, or wherever you get your podcasts. It helps new listeners find the show and we’d appreciate it.

“There’s More to That” is a production of Smithsonian magazine and PRX Productions. From the magazine, our team is me, Debra Rosenberg, and Brian Wolly. From PRX, our team is Jessica Miller, Genevieve Sponsler, Adriana Rosas Rivera, Sandra Lopez Monsalve, and Edwin Ochoa. The executive producer of PRX Productions is Jocelyn Gonzalez.

Our episode artwork is by Emily Lankiewicz. Fact-checking by Stephanie Abramson. Our music is from APM Music. I’m Ari Daniel. Thanks for listening.

I’m obsessed about the band. The band that you’re in, that’s the Syphons?

Taylor: Yeah, the Terminal Syphons.

Daniel: The Terminal Syphons. Okay, and what sort of music do you play at the convention?

Taylor: ’60s rock, blues. We do a lot of Clapton. We do some Billy Strings too. In the physics world, if you get a group of scientists together, you often find a string quartet, but in the caving world, you’re much more likely to find a rock band.

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

- More about:

- Bones

- Caves

- Extinction

- Fossils

- Paleontology

- Teeth

- Wyoming

.png)