Howdy picnickers,

It’s talk submission season — and if there is anything better than writing for both helping you think and getting your name out there as a thinker, it’s speaking. Plus you get to have a cool photo of yourself on stage that you can use in the company Slack and on LinkedIn to project influence. Win-win.

All the calls for submissions have got me thinking about the axioms of my own product development practice; I hesitate to call it a design practice because there are so many other moving parts that are necessary before your users can actually have an experience.

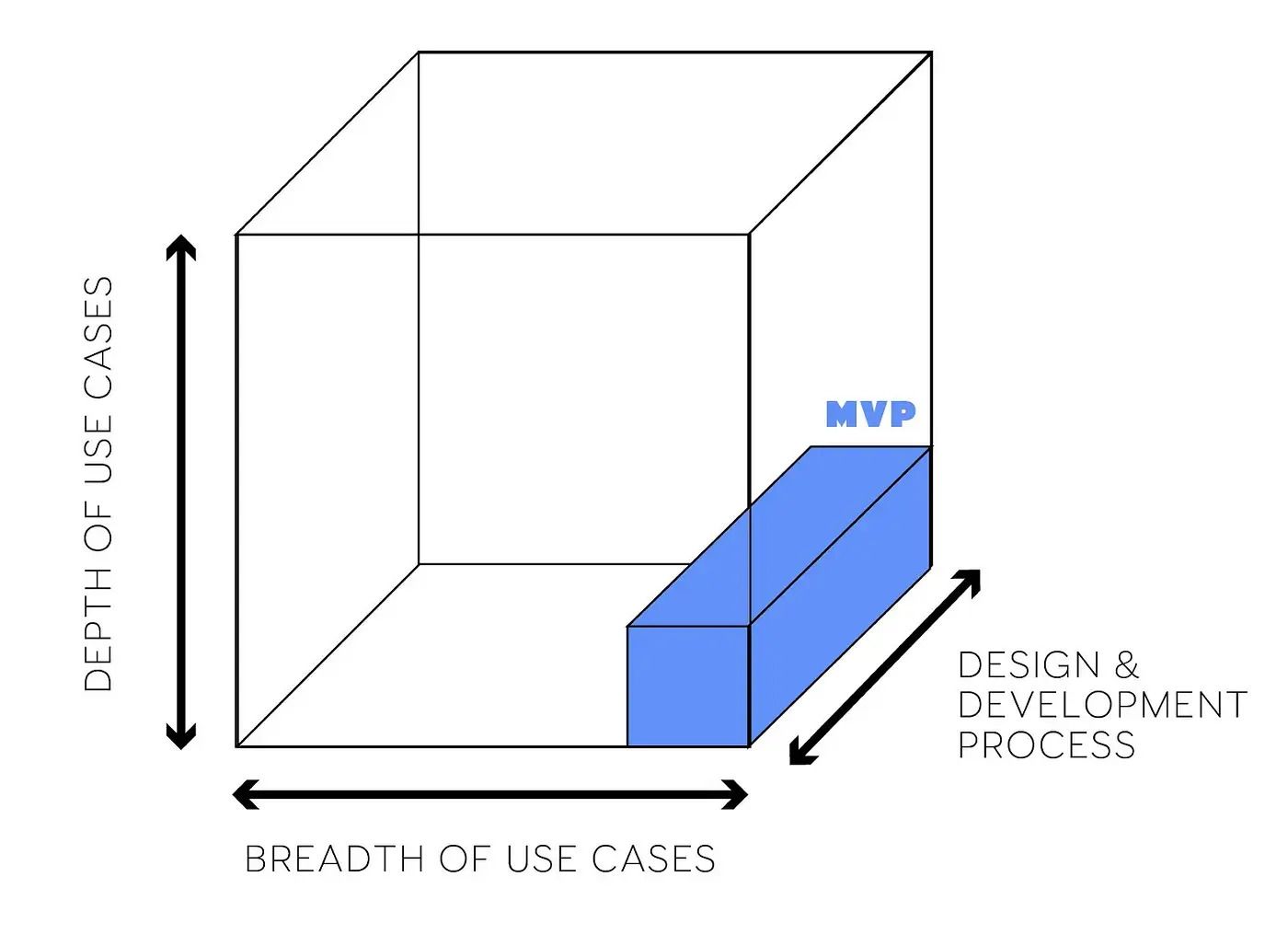

Reviving the diagram of the week section; this one is from my article here

One axiom is: doing design requires that you first establish an environment in which design is possible and valuable. It is insufficient to be able to practice the methods of design if the goals those methods help you reach are not valued in your context.

Another axiom is: doing design means following a design process. While it is possible to produce outputs that resemble design artifacts without practicing the process, you are not designing as such. Of course, there is no hard line between what is and is not a design process; for me it is a set of principles rather than linear steps one can follow.

Unfortunately, that is not the popular understanding of process. Process, in tech circles, has come to mean “following the steps by the book.” This type of process, typically imposed top-down, is universally hated, for good reason: it’s not seen as helping reach valuable goals, but rather solely as a goal unto itself. Workers must achieve their goals despite the process, working around what they are meant to do in order to do what they need to.

To be a good process person requires you to be critical of ineffective processes.

This kind of process “transformation” didn’t start with AI, although AI certainly kicked it into high gear. Various “agile” processes like SAFe have been imposed on unwilling developers for the past two decades, with one common goal: attempting to make releases more predictable through managerial control.

These top-down processes all failed, and will all continue to fail, for one simple reason: certainty can only be achieved through bottom-up understanding of reality, rather than top-down dictation of what executives want to be real. And from the ashes of that failure, a new idea rises: that since everything is broken anyway, the only remaining course of action for a “high agency” contributor is to ignore the system and “just do things.”

That is what the hype-o-sphere around AI promises: forget those ordinary people bound by things like rules and process. Be a heroic knight-errant who can get things done by themselves, and present everyone else with a fait accompli.

Alas, the simplistic narrative is never true.

The irony is that while political and technological developments are encouraging people to “just do things,” these same developments are making human agency harder to exercise, particularly with regard to AI. In the cultural realm, the replacement of artistic choice by AI tools means removing a level of intent and decision-making.

Human collaborators are infinitely more flexible than artificial ones. Anyone determined to work with a machine must inevitable train themselves to think like a machine — because even the most cutting-edge AI is not capable of translating intent into action in a useful way (and the process through which the human operator must do it on behalf of the machine is complex enough to deserve its own academic paper).

The reprogramming goes deeper than that. Learning good AI habits doesn’t prevent you from also developing bad ones. Picking up these tools without extreme intent for what you want out of them will always cause you to fall in line, and adopt them for what’s easiest to produce with them, rather than what you want.

Executives are very happy to nudge this transformation along, because it redirects attention from “is the system (which execs are responsible for) working?” to “are individual workers being productive enough?”

Workers are right to be worried, but not for the reasons they think. They're not being replaced by superior intelligence. They're being systematically deskilled and made dependent on systems they don't fully shape, controlled by people who view them as obstacles to profit maximization.

That is the logic being embraced at Meta today: developers are being ordered to become 5x more productive, without management having the least bit of a clue about how that might be achieved.

And without a coherent strategy for what “more productive” is supposed to achieve, workers prioritize outputs that are easy to produce and measure. Supply-side outputs.

Next week, we’ll talk about what you should do instead: how to design the macro-system that governs what experience ends up being developed.

— Pavel at the Product Picnic

.png)