Culling Road, Canada Water. The stunning stations on the 1990s Jubilee line extension are acknowledged as a high point in London Underground's architectural heritage, but Ian Ritchie's innovative and exciting mid-tunnel ventilation shafts are definitely also worth seeking out for their individuality and beautiful use of materials. The six vents (all different) were built on land compulsorily purchased in locations determined by the JLE route, and these plots varied in size and character, which needed to be taken account of in the designs. At Culling Road the site is next to the Albin Memorial Garden, very important locally, and the architects felt that the building should be particularly special to recognise that. The result is a fantastically quirky pavilion that draws you in with a wonderful intensity of different shades of green and intriguing hints at what is hidden inside. Photo: Judy Ovens.

Culling Road, Canada Water. The stunning stations on the 1990s Jubilee line extension are acknowledged as a high point in London Underground's architectural heritage, but Ian Ritchie's innovative and exciting mid-tunnel ventilation shafts are definitely also worth seeking out for their individuality and beautiful use of materials. The six vents (all different) were built on land compulsorily purchased in locations determined by the JLE route, and these plots varied in size and character, which needed to be taken account of in the designs. At Culling Road the site is next to the Albin Memorial Garden, very important locally, and the architects felt that the building should be particularly special to recognise that. The result is a fantastically quirky pavilion that draws you in with a wonderful intensity of different shades of green and intriguing hints at what is hidden inside. Photo: Judy Ovens.

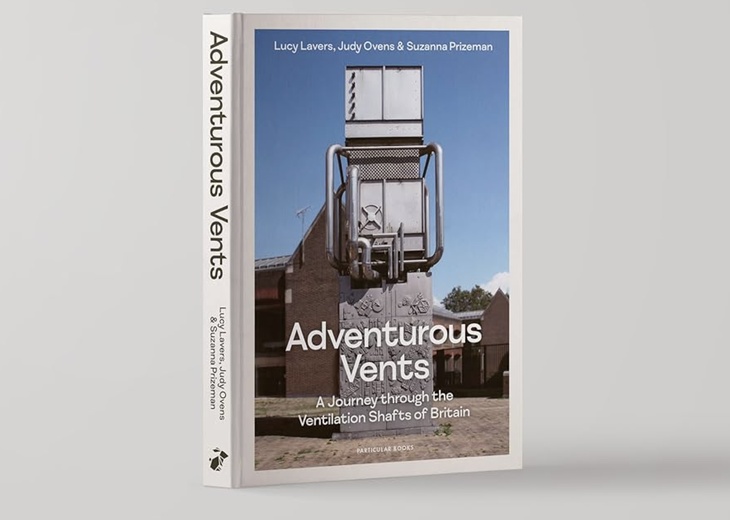

Don't mind if we vent for a minute, do you?

Specifically, to share these photos of London's most adventurous vents — the subject of a new book that's likely to be on the Christmas list of various architecture and design nerds.

New Blackwall Tunnel, Blackwall. Persistent, unalloyed, continuous congestion in a tunnel is no fun: tempers fray, fumes build up, engines overheat and vehicles break down. Such was the state of traffic by the late 1930s in the original Blackwall Tunnel, built for horse-drawn vehicles in the 1890s, that the London County Council was eventually persuaded to build an extra tunnel. The Second World War and its aftermath meant that another 30 years went by before Terry Farrell, a young architect working for the LCC, was tasked with designing the two pairs of shafts. Influenced by Oscar Niemeyer's spectacular undulating concrete forms at Brasilia, Farrell seized the opportunity to create these exceptionally elegant industrial chimneys. The south vent shafts are now within The O2 and difficult to see, but the north vent shafts are easily viewed from the northern approach. Photo: Jonathan Lawder.

New Blackwall Tunnel, Blackwall. Persistent, unalloyed, continuous congestion in a tunnel is no fun: tempers fray, fumes build up, engines overheat and vehicles break down. Such was the state of traffic by the late 1930s in the original Blackwall Tunnel, built for horse-drawn vehicles in the 1890s, that the London County Council was eventually persuaded to build an extra tunnel. The Second World War and its aftermath meant that another 30 years went by before Terry Farrell, a young architect working for the LCC, was tasked with designing the two pairs of shafts. Influenced by Oscar Niemeyer's spectacular undulating concrete forms at Brasilia, Farrell seized the opportunity to create these exceptionally elegant industrial chimneys. The south vent shafts are now within The O2 and difficult to see, but the north vent shafts are easily viewed from the northern approach. Photo: Jonathan Lawder.

Lucy Lavers, Judy Ovens and Suzanna Prizeman have scoured the length and breadth of the country to bring to light these structures which serve as clues to the busy world of tunnels, sewers, bunkers and power hubs that lie beneath our feet.

Western Pumping Station, Battersea. Standing in celebration of Joseph Bazalgette's ingenious sewer network, this stately tower, together with its beautifully detailed adjacent pumping station, is one of the few above-ground manifestations of the system running below. At 272 feet (83 metres) high it commands attention from both sides of the Thames, and its elegant appearance, with tapering sides and Italianate features, reminds us that no utility was too lowly for the Victorians to honour with high-class workmanship. This is the point at which the Low Level Sewer, through which the sewage is pulled by gravity, gets too low to continue, and the effluent needs to be raised 20 feet (six metres) to resume its journey eastwards to Abbey Mills. Photo: Lucy Lavers.

Western Pumping Station, Battersea. Standing in celebration of Joseph Bazalgette's ingenious sewer network, this stately tower, together with its beautifully detailed adjacent pumping station, is one of the few above-ground manifestations of the system running below. At 272 feet (83 metres) high it commands attention from both sides of the Thames, and its elegant appearance, with tapering sides and Italianate features, reminds us that no utility was too lowly for the Victorians to honour with high-class workmanship. This is the point at which the Low Level Sewer, through which the sewage is pulled by gravity, gets too low to continue, and the effluent needs to be raised 20 feet (six metres) to resume its journey eastwards to Abbey Mills. Photo: Lucy Lavers.

While they could have simply been utilitarian slabs of infrastructure, each of the vents featured in the book are instead works of architectural and engineering mastery: undulating concrete forms, diaphanous shirts of red that reference Islamic geometry and Gothic tracery, and razzle-dazzle towers that take their cue from naval history and the patterns found on animals.

Indeed, many of these vents are now Listed, or have won awards for their innovative style.

Bunhill 2 Energy Centre, Old Street. The radical proposal to turn heat from the Tube into usable power emerged from a collaboration between Islington Council, the Mayor of London and Transport for London working with Ramboll Engineers. Together they devised a plan to upgrade an existing vent sitting over the disused City Road station on the Northern line, enabling the heat generated by train engines and brakes to be captured and re-used, rather than released to pollute the atmosphere. The brief for the above-ground building called for an innovative and impressive architecture that would celebrate the technological breakthrough housed within, much as the Victorians had done with their splendid industrial edifices. And the building designed by Cullinan Studio indeed attracts attention, startling with its newness and inviting us to investigate. Photo: Lucy Lavers.

Bunhill 2 Energy Centre, Old Street. The radical proposal to turn heat from the Tube into usable power emerged from a collaboration between Islington Council, the Mayor of London and Transport for London working with Ramboll Engineers. Together they devised a plan to upgrade an existing vent sitting over the disused City Road station on the Northern line, enabling the heat generated by train engines and brakes to be captured and re-used, rather than released to pollute the atmosphere. The brief for the above-ground building called for an innovative and impressive architecture that would celebrate the technological breakthrough housed within, much as the Victorians had done with their splendid industrial edifices. And the building designed by Cullinan Studio indeed attracts attention, startling with its newness and inviting us to investigate. Photo: Lucy Lavers.

Beginning with a fascination with Eduardo Paolozzi's mechanistic vent in Pimlico, Lavers, Ovens and Prizeman launched the 'Inventive Vents' project, which investigated and mapped vents throughout London as well as providing school workshops and public bus, Tube and walking tours. From there, this book was born.

While Adventurous Vents is littered with many London examples, the book covers 100 vents in all — in locations as diverse as the Levant Mine in Cornwall, Fraserburgh Sewer Pipes in Scotland, Hafod Copperworks in Wales and Ness Point Tower in Lowestoft.

Optic Cloak, Greenwich. Now you see it, now you don’t! Well, not exactly, but the shiny, undulating tower on the Greenwich Peninsula is certainly shape-shifting and well named as the Optic Cloak. When Conrad Shawcross was commissioned to create a wrapper for the Low Carbon Energy Centre flues, the developer, Knight Dragon, asked for an architectural artwork that would both disguise the vents and serve as a landmark gateway to its huge development. The centre, designed by C. F. Møller Architects, was created to provide cleaner and cheaper power for the new neighbourhood, and Knight Dragon was clearly keen to advertise its espousal of greener energy with the shimmering shaft. Shawcross, fascinated by the disguise element, took inspiration from animal patterns and man-made 'dazzle' naval camouflage as well as Op Art. Thousands of perforated aluminium triangles are hung from the underlying steel structure and overlaid so the holes match up in myriad patterns, causing the illusion of constant motion. The cloak magically transforms, dependent on where one is and the quality of the light. Photo: Suzanna Prizeman.

Optic Cloak, Greenwich. Now you see it, now you don’t! Well, not exactly, but the shiny, undulating tower on the Greenwich Peninsula is certainly shape-shifting and well named as the Optic Cloak. When Conrad Shawcross was commissioned to create a wrapper for the Low Carbon Energy Centre flues, the developer, Knight Dragon, asked for an architectural artwork that would both disguise the vents and serve as a landmark gateway to its huge development. The centre, designed by C. F. Møller Architects, was created to provide cleaner and cheaper power for the new neighbourhood, and Knight Dragon was clearly keen to advertise its espousal of greener energy with the shimmering shaft. Shawcross, fascinated by the disguise element, took inspiration from animal patterns and man-made 'dazzle' naval camouflage as well as Op Art. Thousands of perforated aluminium triangles are hung from the underlying steel structure and overlaid so the holes match up in myriad patterns, causing the illusion of constant motion. The cloak magically transforms, dependent on where one is and the quality of the light. Photo: Suzanna Prizeman.

"Almost invariably," writes the trio of authors in the book's introduction, "people say 'How niche' when hearing the subject of our book, and we nod somewhat apologetically in agreement. But, given that all underground spaces need ventilation, and there are many of them, all over the country, it isn’t really niche at all: it’s just that the ventilation shafts themselves are often overlooked and rarely spoken about."

Camberwell Submarine. Once lonely and marooned in the middle of a dual carriageway, slated for demolition and known largely only to locals, the Camberwell Submarine has become something of a celebrity among vents since being put back into commission. And this is no surprise, as it is one of the most unusual and interesting in London. Having very much a Cold War aesthetic, it has always inspired talk of nuclear bunkers and been the focus of many an urban myth. But the reality is that it is something perhaps less exciting, but much more useful — ventilation for an underground boiler house that was constructed in the 1970s to provide heating and hot water for surrounding social housing estates then being built by Lambeth Council. When the boiler room was no longer required in the 1990s the future of the Submarine was put in peril, and attempts to list it came to nothing. However, a regeneration scheme of the area in the 2010s, although somewhat controversial, put the Sub back in use, thereby ensuring it can continue to weave its mysterious magic on passers-by. Photo: Lucy Lavers.

Camberwell Submarine. Once lonely and marooned in the middle of a dual carriageway, slated for demolition and known largely only to locals, the Camberwell Submarine has become something of a celebrity among vents since being put back into commission. And this is no surprise, as it is one of the most unusual and interesting in London. Having very much a Cold War aesthetic, it has always inspired talk of nuclear bunkers and been the focus of many an urban myth. But the reality is that it is something perhaps less exciting, but much more useful — ventilation for an underground boiler house that was constructed in the 1970s to provide heating and hot water for surrounding social housing estates then being built by Lambeth Council. When the boiler room was no longer required in the 1990s the future of the Submarine was put in peril, and attempts to list it came to nothing. However, a regeneration scheme of the area in the 2010s, although somewhat controversial, put the Sub back in use, thereby ensuring it can continue to weave its mysterious magic on passers-by. Photo: Lucy Lavers.

Get this book on your shelf, however, and you'll be having conversations with your house guests about vents for years to come.

Adventurous Vents: A Journey through the Ventilation Shafts of Britain by Lucy Lavers, Judy Ovens and Suzanna Prizeman, published by Particular Books.

We featured this book because we know it's the kind of thing our readers will enjoy. By buying it via links in this article, Londonist may earn a commission from Bookshop.org — which also helps support independent bookshops.

.png)