I thought fashion was stupid: A shallow and vain pursuit. A waste of time and resources. An unnecessary signaling game.

We tend to keep our distance from the things we dislike, so we rarely understand the targets of our disdain. I didn’t understand fashion and I didn’t want to.

I figured the only way to win was not to play. But I never fully opted out.

You can’t.

We are always sending out secret messages about who we are through our appearance, words, and actions. People use these messages to give us opportunities, connection, or criticism. What we wear is the one of the top avenues people have for quickly forming opinions about us.

The world has to look at us whether it wants to or not. Refusing to play the game means leaving what we signal up to accident. Fashion is the practice of identity and narrative-crafting. It isn’t shallow at all, but soul-deep, asking us who we aspire to be and how we want to be seen.

But I didn’t know any of that.

A few trips to New York and LA had me feeling like an outsider who didn’t belong. If I dressed better, could I be more successful? I started to suspect the answer was yes.

But where would I start in this domain I knew nothing about? Fashion felt like poetry: mysterious and artistic, where only the fortunate few could be proficient.

Now I believe taste in fashion is something that anyone could have. If you want it. And it’s worth wanting.

In this essay, I describe the systems I used to take control of this domain I knew nothing about.

Maybe this is obvious to you.

For most of my life, my implicit belief was that clothes are comfortable, useful things to deal with your environment. How they’re perceived isn’t important.

Anything more than that seemed like a waste. Could we all just coordinate to not spend thousands of dollars on a signaling competition? Can we agree that runway clothing is impractical? To my value system at the time, it was all a waste.

The other implicit belief: clothes should be normal. They’re not for expression or standing out. At best they’re invisible, inoffensive, fine.

Unsurprisingly, this didn’t create a good environment to learn how to dress myself well.

Buying new clothes was a challenge. I had a limited comfort zone for clothing I could consider wearing. Thinking about clothing was painful and confusing. So I’d wear the same few things and try to make them last.

Ten pairs of black underwear, all identical grey wool socks. My closet was small, colorless, and bland.

Sometimes I’d feel wistful, vaguely knowing there was something more to fashion and feeling left out. Sometimes I’d feel mad and jealous. I was the superior one, opting out of this stupid game!

So why care?

Well, I didn’t look so good. And looking good would get more of what I want: respect, influence, money, belonging, and success.

Over the next few years, I flailed.

I bought random things that seemed cool. Most experiments were failures. Some failures helped me learn something: Avoid halter tops. No hot pink. It was a slow and inefficient process.

What worked a little better was copying friends with taste. I’d buy from the designers they were into and wear their hand-me-downs. But it was their taste, not mine.

Even if an item of clothing worked for me, I didn’t understand why some things worked and some didn’t.

All I had was a closet full of random “cool” items that didn’t work well on me or with each other. I needed to try something different.

About a month ago, I decided to get serious.

It started with a dialog with the best LLM of the day. I fed it photos of my outfits, my wardrobe, and things I might buy. I asked it to help me clarify my intentions, suggest rules, and develop a fashion thesis. I asked for resource recommendations to learn more. Sometimes it bullied me into buying specific things—and it was right.

(I used LLMs extensively. Rather than say so in every paragraph, I’m saying it once here. If you’re wondering how I did a certain step, the answer is probably “I had a discussion with the LLM in a project with all the relevant context.”)

This was the start of an expensive month-long fashion-obsession rabbit hole.

My previous efforts failed because the goal of “looking better” was too vague. The first step in tackling an engineering problem is defining the problem. The more concrete and meaningful a goal, the easier it is to be motivated towards that goal.

What do I want? Get specific.

How can I tell if I’m getting closer or further?

For whom am I dressing?

For what occasions am I dressing?

I want to impress men who care about or notice fashion. I want to avoid looking like an uncultured clown. I want to look hot and to convey wealth, skill, and elegance through dress.

Usually, we’re better critics than we are creators. We can tell if a singer is bad even if we can’t sing to save our lives. I can sort of tell if I’m onto something just by looking in the mirror.

But as a fallback, I have metrics, too.

Some potential metrics are things like personal wellbeing, success in dating, or client conversions and sales. Mine are things like “lingering glances” and getting taken to very nice places.

An aside on compliments: Many aesthetic choices work even if they’re not consciously noted. Compliments are a noisy signal that mean my clothes are standing out, not me. I’m optimizing for the five-hour impression over the five-second impression.

Different cultural scenes have different visual identities for what makes someone high status. We have to decide what social microcosms we want to be high status to: basketball players, bohemians, bankers? We can’t please everyone.

I asked the LLM to generate 10-20 user stories: portraits of successful men that I would like to appeal to because they are appealing to me, and tested my outfit ideas against them. This was a helpful place to start.

Later, I found people who served as examples of these archetypes in my own life. I could test my ideas directly—a much more rewarding experience.

Even if fashion is “just signaling,” signaling is communication. It finally clicked in my nerd-brain when I realized this is character design. Your outfit hints at your lore and tells people who you are. Change your character’s class in a video game and, often, the only thing that visibly changes is what they’re wearing.

This is the most existential part of this project. At first I thought I was just trying to dress better, and now I was confronting who I was and who I wanted to be.

What do your current fashion choices tell people about who you are?

How do you want people to see you?

“The purpose of a fashion designer is to use the alchemy of clothes to propose a hypothetical identity that can mix with and complicate your own identity” -Bliss Foster, Are Fashion Brands Stealing Your Identity?

You don’t need to have just one character. You can play with being different characters.

The identity can be aspirational. But there should be something authentic about it, or it won’t feel right. If it gives others or yourself a sense of cognitive dissonance or if they can tell you’re uncomfortable, you won’t have the effect you want.

A shy nerd wearing extreme hip-hop fashion, an unkempt kid dressing in preppy “old money” style, or frilly cottagecore dresses in a grungy city environment might all feel incoherent and off.

Even if on the inside the cottagecore girl is committed to the tradlife fantasy, it might look like a costume to everyone else. The best way to tell, though, is: does it feel right? Does it feel like a costume or is there something in it that feels authentic?

The character should make sense in the context of your environment. The character must be inspired by and align with both your sense of yourself and other’s sense of you.

Finding our characters takes time and introspection. We might think we want to be seen in one way, but it just doesn’t work in practice. And as we change as a person, we may need to rethink our character design.

What I came up with for my character doesn’t have an easy name to sum it up. Something like “chic/sexy cafe blogger intellectual”. She’s tasteful and a bit quirky. She plays the piano and likes talking about the Roman Empire.

Next, a ritual to summon this version of myself through clothing!

I distilled all that—my goals, target audience, character—into three adjectives that will evoke the character I want. This is what I ended up with:

architectural • sensual • whimsical

Every outfit should have these elements.

Architectural: structural, clean geometry with outlines that are strong and intentional (no ruffles or busyness)

Sensual: Appealing without shouting. Body-hugging, soft-to-touch textures, something revealing that draws you in

Whimsical: A witty, unique flourish to add personality and deepen the lore

No more chaos of infinite options. Limitations create possibility.

To operationalize further, I created a list of guidelines to follow:

Only use gold as an accent metal

Use natural fabrics and textures like knits, wool, alpaca, cashmere, silk, suede, and velvet

Deep warm palette (olive, chocolate, aubergine, terracotta, mustard)

Each outfit should have one accent / focal point, preferably near the face

Each outfit should be revealing or suggestive in no more than one way (open back, thigh slits, cleavage)

Good fit is a luxury. Tailor early and tailor often.

Avoid logos and trends. Try to find things that will look good 5-10 years from now

Add a point of tension. Too perfect reads as anxious and try-hard

These developed from my thesis as well as my personal preferences. They’re informed by cultural understanding of what different motifs mean. Some of these are universal, like “good fit is good”. Others come from trying to achieve certain goals, like “be sexy without being low-status”. Some are more subjective, like “gold only”, but that still has cultural meaning that helps me tell my story: warmth, richness, glint.

My buying rules:

Any new item must work with at least 3 other pieces in my wardrobe

Spend more on things I would wear often. Luxurious everyday > rare event pieces

Do I genuinely like it or does it just look good on paper?

If I follow these, my closet will be coherent with itself.

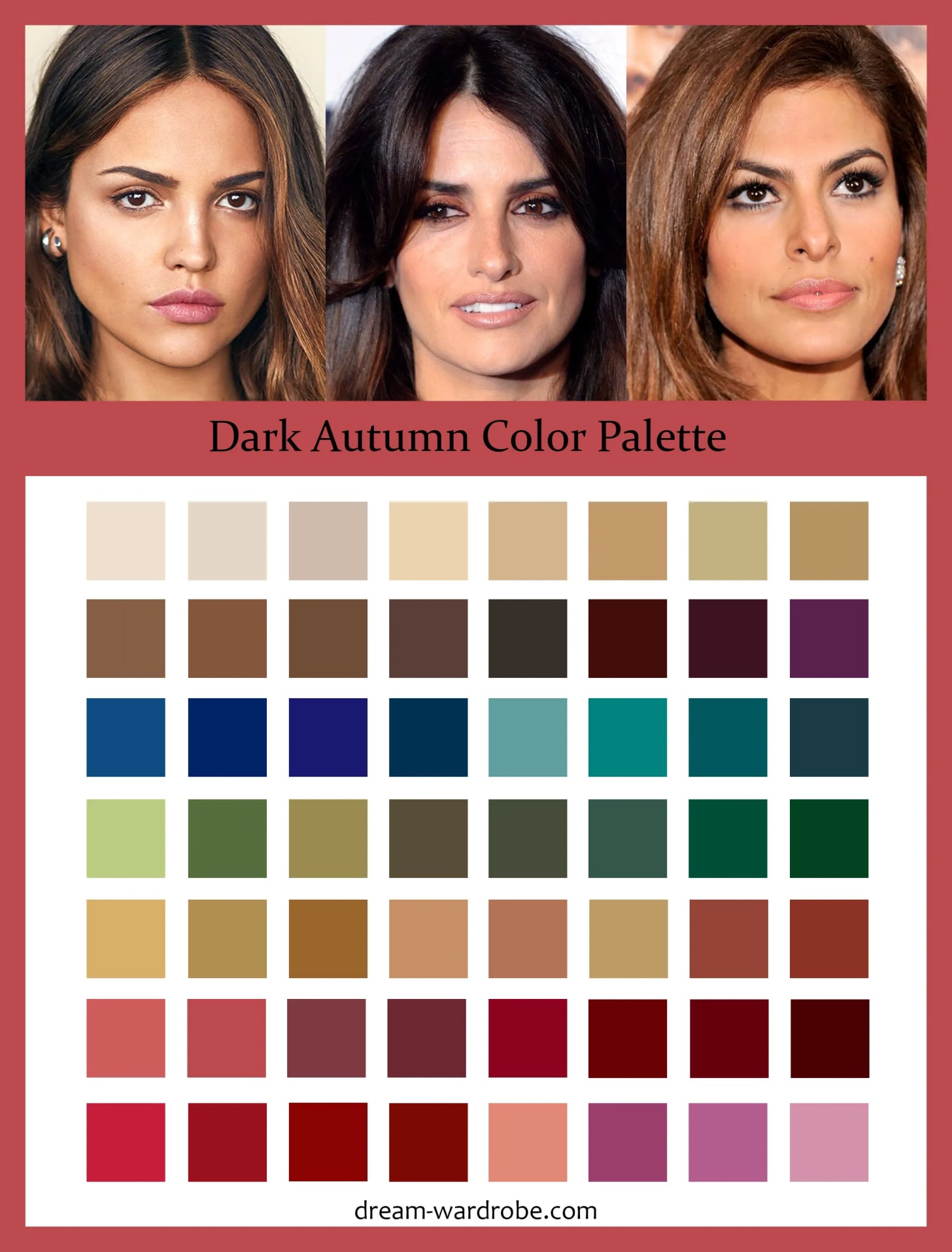

I paid a color analyst a few hundred dollars to hold swatches of cloth to my face and say things like “hmm, this color makes you look dead” or “this brings out the purples in your face”. She determined that my ideal color palette is dark autumn.

The basic theory is that our features have contrast, saturation, and warmth/coolness. Wearing colors with the same level of those will harmonize our whole look.

Ideally, our faces and our clothing should be equally easy to look at. One shouldn’t draw more attention than the other. Otherwise, either our clothes or our faces will look bland, drained, and dead.

If all your clothes are in the same season, they’ll also go well with each other. None of your clothing will clash, and building outfits becomes easier.

Am I really a dark autumn? This is a system humans invented. Not all people perfectly fit into one of eight categories. But for most of us, it’s an approximation that simplifies things.

If you recognize you’re bad at something, talk to someone more skilled than you. One shortcut is to hire an expert and get them to explain things.

I worked with a stylist to plan a photoshoot and got more than that. She quickly expanded my Overton window for what I thought I could wear and helped fix my shoe blindspot by getting me to buy proper heels.

The better you can describe your own sense of style, the better suggestions a stylist will give you. Now that I know more, talking to her again will be more useful.

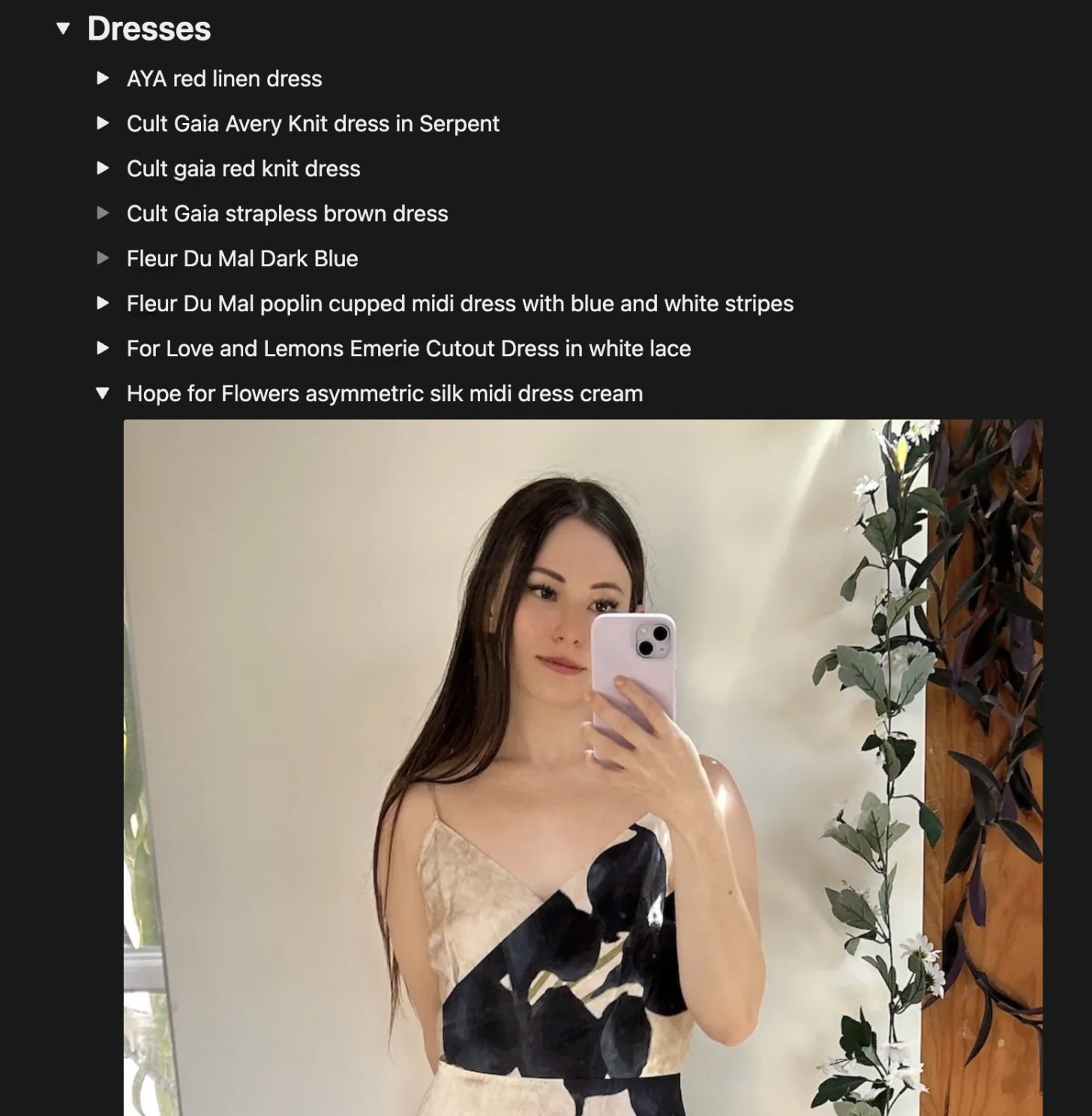

My closet was large, messy, and redundant. Sometimes I’d buy new clothing because I would forgot what I already had. So I built out a Notion doc with everything I owned, complete with photos of me wearing those items. I figured that it would save me from duplicate purchases, but it’s done more than that:

I rediscovered amazing articles of clothing I forgot I had

Stylists, assistants, and LLMs can style me from afar

Planning photoshoots and packing for trips is simple

I can more easily get rid of the things I don’t like, don’t fit my style thesis, or are redundant

Most of the photos are either thirst traps or from professional shoots. It’s a fun document to have.

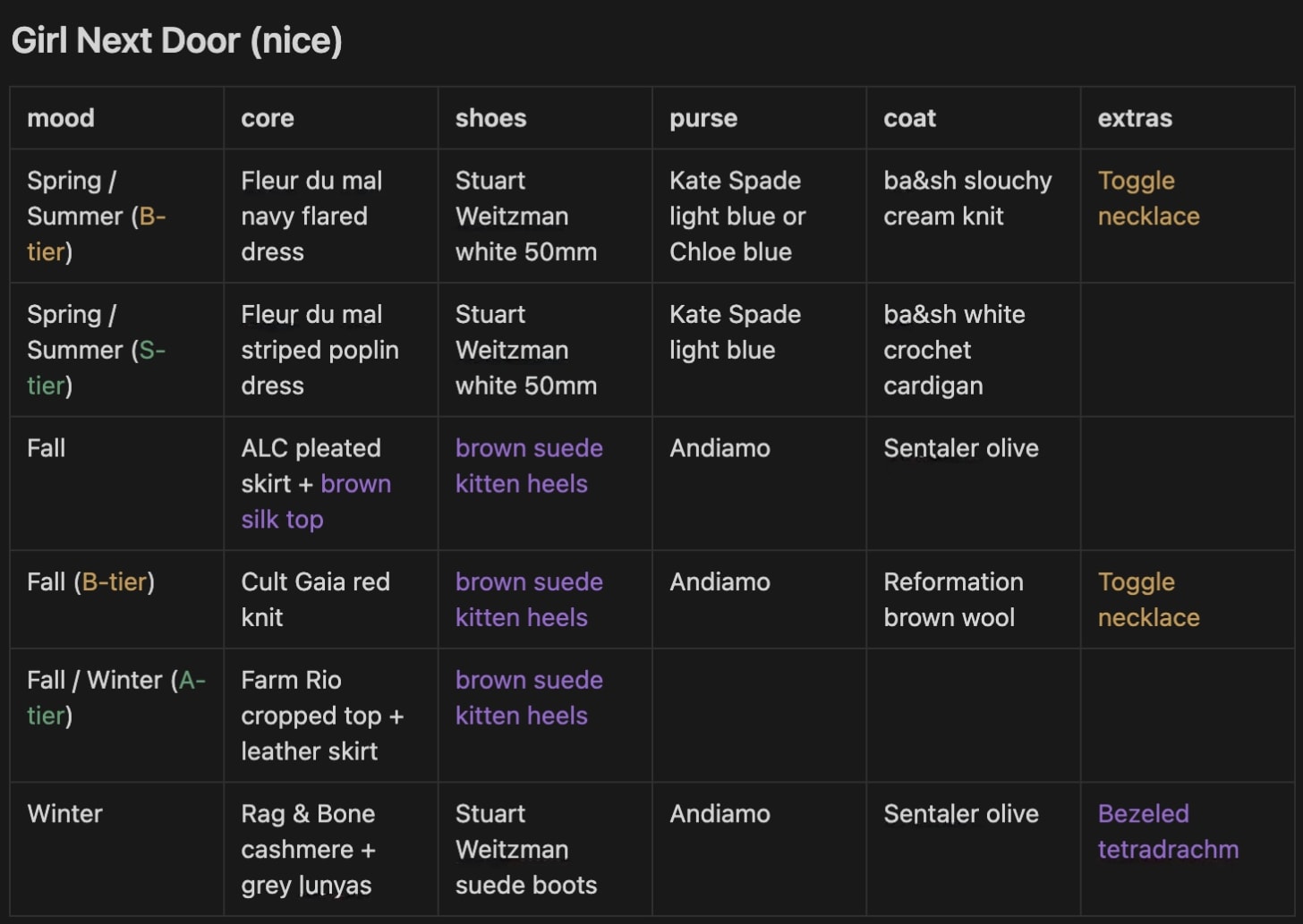

I like to get dressed quickly, a habit from my “clothes are just functional” days. Left to my own devices, I’ll wear what I wore yesterday. Figuring out what to wear takes effort. I wanted to design outfits once and be able to easily refer to them in the future.

I built out outfits by season and occasion using the items from my closet doc. Then, I could see what I needed and could find the fewest items that would complete the most outfits.

Looks like I either need brown suede kitten heels or something that serves a similar purpose.

You want to create harmonious outfits, not look like you haphazardly rolled through a pile of “cool stuff” -Derek Guy, A Tale of Two Shoes

It’s like solving a logic puzzle.

Now, to create something new.

I wanted another nice-casual fall outfit, so got some ideas from an LLM as a starting point and drafted them up in Photoshop. This is a good sanity check for color and style coherence. A subgoal I had when developing outfits was for each element to be reusable across multiple outfits. That’s how you create a capsule wardrobe, where a small amount of essentials can be mixed and matched to form a large variety.

Could this be me? Why does looking at this make me feel so good?

This felt like more than mere optimization. It was an expressive joy to feel the harmony of the sketch and luxuriate in how sensible it was.

I tried it on.

It didn’t work out in practice. But the feedback loop shortened. I kept iterating, changing the elements out that didn’t work, and created an outfit that did work soon after.

At the start of this project, I thought I could game the system and succeed without knowing anything about fashion. But fashion is a cultural language and I must know the opinions of others. The clothing I chose wouldn’t have the right impact if I didn’t understand the signaling and significance of what I was wearing. It’s not just about me.

I started researching everything I could.

This took a while.

I built up a sense of the field: the business of fashion, the big brands, the major trends, how fashion critique works, how people discuss runway shows or new collections. And even just mundane facts that make me look less clueless (like how to pronounce “Loewe”—look it up, you won’t figure it out on your own).

These are questions that seemed obvious, but are actually deep:

Who determines taste? Where does the idea of “good taste” come from?

What makes something high quality?

What is luxury? What is luxurious to you?

How did we get here, to the clothing we have today? What did it mean in the past vs today?

Now I understand the basic building blocks. I can throw in some idioms of fashion, little insider tributes like the Maison Margiela Tabi shoes.

You can identify Chanel by the colorful tweed. Before Chanel, tweed was a masculine, serious fabric. Putting it on women was modern, chic, and tomboyish. And even though I couldn’t have consciously said any of that before, the language Chanel was using to communicate was still having subconscious effects on me.

Fluency is understanding the styles, types of clothing, materials, designers, and motifs on an intuitive level. It takes time to learn a whole new language.

It’s been a month since I started on this journey. I created some outfits I’m proud of and have set down my credit card. Now it’s time to wear my new fashion, see what the world thinks, and iterate.

I don’t feel lost anymore.

Because of this framework, I’ve finally felt confident enough to seriously invest in jewelry, purses, and shoes. Turns out—shopping is a skill. It doesn’t have to be stressful.

My outfits have greater harmony. They boldly state who I am and who I want to be.

Not only can I add to my closet more skillfully, I can subtract, identifying and removing the clothes that were only burdening me.

I’ve been able to use my process to help others improve their fashion on their own terms. Now, I try to critique people’s fashion choices with reference to what they’re trying to do, rather than measuring them against my goals. More analysis, less judgement.

But the deepest prize is that I have newfound love and appreciation for an expressive art form. I’m spiritually richer now.

Fashion isn’t shallow. Dismissing it was. I was rejecting a nuanced and beautiful facet of social persuasion, important in every society, which is continually refreshed by some of the world’s greatest creative minds. All of this will be true of fashion as long as human beings are still recognizable.

Before, I was locked out of connection with those who cared about fashion. I had given up power and agency over how I was seen. And I was missing out on the trickster-like fun and self-discovery of playing with different identities.

What else I might be dismissing as shallow that is actually profound?

Perhaps some of the cultural distaste for fashion is a coping mechanism. We have complicated relationships to being seen. We have to admit that we have power over others via how we show up and what we wear, and we have to be brave enough to embrace that power.

Some of the distaste may be the fear of what we don’t understand. If fashion is pure aesthetic subjectivity, “wear what you like and just be yourself”, we can’t improve. We’re generally not taught the meaning, principles, and systems that allow us to train and refine our taste.

When we dress, we’re creating an intimate experience for our viewer. We pull something out from deep inside ourselves, put symbols of it on our bodies, and let their meaning enter someone else’s psyche.

No matter what, we’re having real aesthetic impacts on people. To develop and deploy taste is to take control.

I had to learn a lot to write this blog post.

Die, Workwear! How to Develop Good Taste Pt1, Pt2, Pt3, Pt4 (Different experts weigh in on what they think good taste is)

CJ the X, How Jordan Peterson’s Suits Taught me Fashion (Fashion as communication between wearer and viewer)

Stephen Bayley, Taste: The Secret Meaning of Things (The history and social mechanics of taste)

The Business of Fashion, “The Debrief” podcast (Industry context)

Avery Trufelman, Articles of Interest (Case studies into the history and deeper meaning of the things we wear)

Bliss Foster’s YouTube Channel (Runway as philosophy, designers as world-builders)

.png)