Every time I read the Declaration of Independence, I can’t help but to feel admiration. There's something audacious about those words—brilliant, cocky, and epic in their scope. For the first time in human history, a group of people looked at monarchy and said, "No, we're going to try something different. We're giving full freedom a chance." Without that moment of defiance in 1776, I wonder if the entire world might still be bowing to kings and queens.

But what does it actually mean today? And honestly, who cares??

That question haunts me because America has done so many things that directly contradict the promises written in that document. The list is so long and painful: slavery, racism, cronyism, tribalism, failed wars, needlessly destructive regulations in housing, medicine, and industry, etc. These aren't abstract policy failures—they're betrayals of the very core of what was supposed to make America different.

One particular betrayal cuts deeper than the rest because it nearly destroyed my life: immigration restrictions.

The United States was the original author of the restrictive, "guilty-until-proven-innocent" immigration regime that is the global standard today. These laws made it so impossible for me to get a visa that I was forced into a nightmare I can barely speak about—becoming a sex slave to a trafficker, just to get the permission to escape from Iran. The permission which they had taken away from me simply because of where I was born.

Today’s immigration system has its roots in the Confederate states, and it became federal law through the Immigration Act of 1924. A legislation so restrictive and exclusionary that it inspired and fueled the Nazi movement, unleashing a wave of nationalist hatred across the world.

How do you reconcile this with “all men are created equal”? How do you explain a country that speaks of liberty while creating systems of bondage? For the longest time, I could only conclude that America had either stopped believing in the Declaration of Independence completely, or perhaps never believed in it at all.

In my darkest moments, that is what I felt was true.

But for some reason, I couldn’t remain despondent. No matter how much I wanted to maintain that cynical view, something would always break through; moments of pure awe and gratitude for the wonders America has created. The brilliant music that has been created. The highway networks that somehow work, seamlessly connecting millions of people across impossible distances. The abundance of food that almost magically never runs out. The perfect, invisible harmony between millions of codes and components that gives us the internet, connecting us to the entire world with a few taps on our phones.

Coming from extreme poverty in Iran, I couldn't take any of that for granted. I've seen too much misery, ignorance, and backwardness during my childhood to be cavalier about modern life. I knew Thomas Hobbes was right when he described the natural state of human existence as "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short." I've lived close enough to that state to recognize what an achievement it is to escape it.

When I was in Iran, I couldn’t walk alone on streets with safety because I was too skinny and non-threatening; I was a prime target for mugging. We couldn’t afford to throw away food, because we didn’t know if the same food was going to be on the shelves next week. The dentists couldn’t treat a cavity; they wanted to pull my teeth instead—the same teeth that dentists in Europe filled with minimal invasiveness. I couldn’t open up to anyone because in Iran, just like in most of human history, the penalty of criticizing religion or the regime was death.

Yes, the modern world has serious problems, some of them grave and urgent. But while the unsolved problems scream for our attention, all the solved problems hide in plain sight, tucked behind a mentality that treats justice, dignity, and a comfortable life as god-given rights rather than the marvelous achievements that they are.

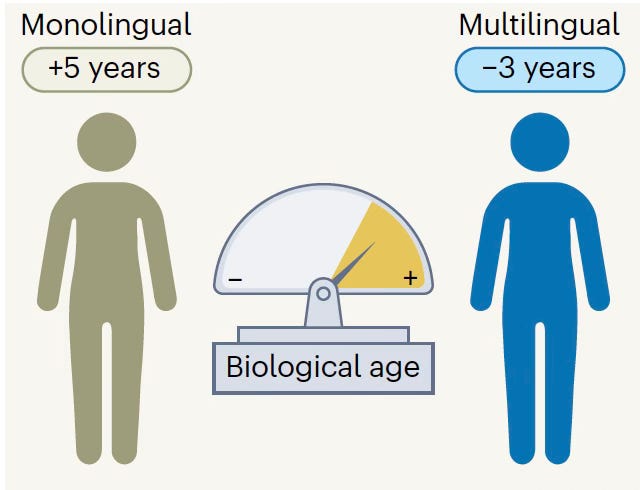

I think about this tweet from psychologist, and my friend,

all the time:

A part of me was initially hostile to this: “who cares about America’s strengths when its immigration system is so broken that it takes 20 years to bring my beloved 10-year-old brother here, away from the war in Iran?! America is playing politics with his life!”

But victims of injustice, more than anyone else, need to work hard to see the good. When you're emotionally overwhelmed by what's wrong, it becomes harder—and yet even more crucial—to understand what's right. Not to excuse the failures, but to muster what it takes to find a path forward.

Once I deliberately shifted my perspective from "everything sucks" to "how come some things don't suck?" my entire reaction changed. Instead of asking "Why isn't America living up to the Declaration?" I started asking "My goodness, America has actually lived up to the Declaration multiple times?!"

The bad cannot erase the good. Nothing America has done since can erase the shining fact that New England states abolished slavery immediately after the Revolution. No amount of xenophobia can change the fact that immigrants like me used to be warmly received by the majority of the Americans. The passage of the reconstruction amendments was America living up to its ideals in real time. The recent advances in gay rights—the equality that my husband and I now enjoy—represent American freedom in action.

I go back to this speech of Frederick Douglass to get a feel for what an unbelievable achievement the passing of 15th amendment was:

I have no fixed and formal speech to make to you to-day. The event we celebrate is its own best speech. It exceeds all speech, and language is tame in its presence. It has rolled in upon us a joyous surprise, and seems almost too good to be true.

You did not expect to see it; I did not expect to see it; no man living did expect to live to see this day. In our moments of unusual mental elevation and heart-longings, some of us may have caught glimpses of it afar off; we saw it only by the strong, clear, earnest eye of faith, but none dared even to hope to stand upon the earth at its coming. Yet here it is. Our eyes behold it; our ears hear it, our hearts feel it, and there is no doubt or illusion about it. The black man is free, the black man is a citizen, the black man is enfranchised, and this by the organic law of the land. No more a slave, no more a fugitive slave, no more a despised and hated creature, but a man, and, what is more: a man among men.

Freedom is real. And it isn't just some old history. It's in our communities, in our friends, in the way we think. We are living it. So how can we allow ourselves to be blind to it?

It's not only a legacy from the past, either. The vast majority of Americans have developed a form of practical liberalism—a live-and-let-live, pro-agency attitude that says everyone should be able to live a good life. This is incredible. This does not exist in other countries. And this should be the dominant force in American politics.

When I ran out of money and was reduced to begging for food on the streets of Seoul, my Korean friends listened to my story, held my hand, and cried. They didn’t do anything but express their sympathies to my plight. When I told someone in Poland that I was being held in an apartment as a slave against my will, they cursed the country and said they wished they could do something.

When I told a group of Americans I had met online that I was afraid of going back to Iran, they assembled in a flash, crowdsourced a fund, reached out to friends, and found a way to help me come to America, even though I had never told them the worst parts of my story. That success was replicated recently when I asked for help on behalf of my friends last month.

If this is not the spirit of the Declaration of independence, I don’t know what is.

Yes, Americans—even including some of the people who helped me—hold many irrational ideas; some are afraid of foreigners, some are resistant to progress, some are too suspicious of profit, most are too quick to tear down rather than build up. But these don't have to be the dominant characteristics of America. These traits don't have to be what defines the national character of America like they are today.

And you know what? Every other country has more or less the same problems, plus a few more that America doesn't have. For every American flaw (like racism) that Iran lacks, Iran has two flaws that America has resolved in turn (especially relevant in the context of Whoopi Goldberg’s recent comments on Iran).

The better side of America still exists. The side that believes in the Declaration still lives within us today. And if we focus our hearts on cultivating the good instead of just lamenting the bad, we'll reach those ideals sooner than we think.

Without what happened on July 4th, 1776, we wouldn't have as much hope for improvement as we have today. That declaration created something new in the world: the idea that ordinary people matter, that they could govern themselves, that rights came from being human rather than from the accident of birth.

Happy 250th Independence Day to all, especially to those of us who have cause to be down on America. Because we need this celebration the most.

.png)