7th of June, 2025

Hermann Ludwig Heinrich Count of Pückler-Muskau was born in 1785 to the Earl Pückler and was later granted sovereignty over his land by King Friedrich III. His fame is unbroken today, but not because of his political power, but because his house chef named a dessert after him. In German and Dutch, the now popular combination of chocolate, vanilla and strawberry ice cream is called Pückler Ice Cream.

When the count wasn't busy snacking on novelty sweets, he liked to engage in his other favorite activity — landscape gardening. Having traveled through England at length, he developed a taste for this exclusive art and lamented that his compatriot aristocrats in Prussia were content with comparatively poorly designed pleasure grounds. To educate and promote good style, he authored the classic Hints on Landscape Gardening.

When the count wasn't busy snacking on novelty sweets, he liked to engage in his other favorite activity — landscape gardening. Having traveled through England at length, he developed a taste for this exclusive art and lamented that his compatriot aristocrats in Prussia were content with comparatively poorly designed pleasure grounds. To educate and promote good style, he authored the classic Hints on Landscape Gardening.

The work is simply great fun to read today. It covers all aspects of the landscaping process, starting with basics like how to transplant trees and moving all the way to advanced topics, like how to prevent commoners from chopping the trees back down.

Perhaps our own estate is too small to host a Bowling Green, a Hunter's Lodge or even a simple Pavilion, but the presented ideas are still useful to toy with. Landscaping a park is the archetypal example of making an environment. Whether we're writing an IDE, designing an open-world RPG, or making a maze for your pet rat, these lessons apply.

Parks are a bit awkward. They are space-constrained, but designed to be walked around in for a long time. This leads to the need for winding paths, which are again awkward. "Why do I have to walk around this corner when I could just go straight?" is a natural reaction of anyone traversing an artificially curved path: "Oh right, I'm doing this for leisure." It reminds us of that suspicion that our life is pointless, which is rather rude.

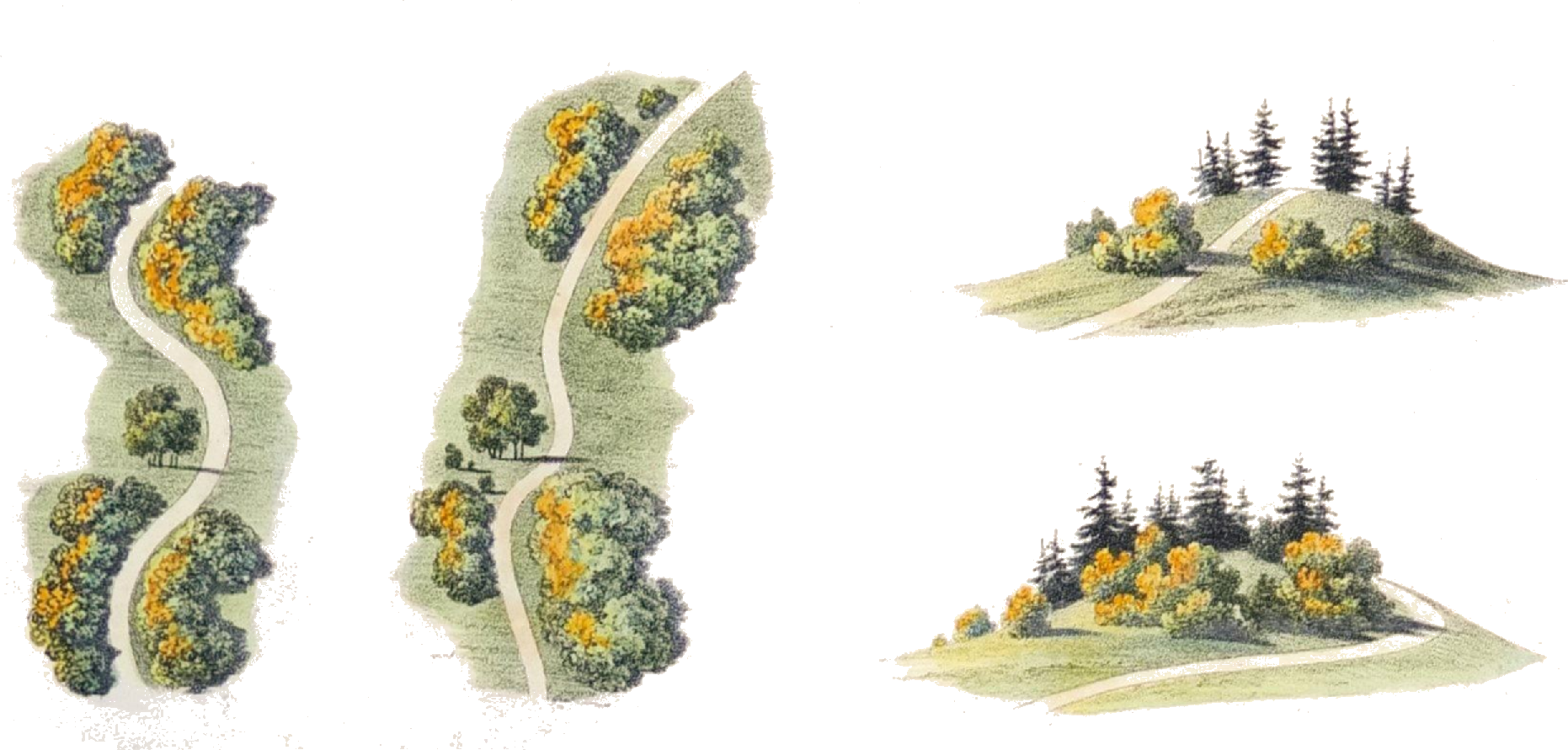

The solution to artificial pointlessness is an artificial point. We give the path a reason to curve. The figures show four ways to make a simple curve more enjoyable to walk through. Just imagine the betrayal you would feel if the tree or hill wasn't there, and how satisfying these are in comparison.

The user wants to see why the path curves is necessary, even if the real reason is invisible. It is not enough that our solution is the best option; it has to look like the best option locally to be acceptable. We learn a first lesson.

1) Show the obstacle.

Having solved the curve problem, the park might end up more fun to walk through than if we hadn't been space-constrained at all. Pückler writes that a big park often gives one great view, but only that — one great view. If you have an expensive castle and a huge estate, it's hard not to show it off. The comparison of St. Peter's Basilica to the Pantheon is given: Because the basilica is more than triple the height of the Pantheon, the main dome with an identical radius ends up looking unimpressively small.

In landscape gardening, we can avoid boring the visitor with show-offs by controlling the foreground. A particularly pretty sight should stay hidden for most of the route, or at least partially obscured. Then, finally, we draw the shrubs out of the line of sight as the path homes in on the spectacle. Such anticipation, such drama! The foreground is much cheaper to control, and thus allows more iterations. Instead of moving the castle, we move the shrubberies.

A modern example, both good and bad, are the recent open-world additions to the Legend of Zelda series. Undoubtedly they have great map design, but incessantly clearing sight by climbing on everything disenchants the well-designed landscapes. From a landscape gardening perspective, the final boss isn't Ganon, but that mechanic of climbing a vantage point tower all the time. Reflecting on different locations, it seems like the narrative tension is inverse proportional to how much is actually visible on the screen. In contrast, the gray rocks that surround the camera in Metal Gear Solid V feel weirdly engaging, because said rocks are always nicely framed by the foreground serving as Snake's cover.

The castle of our park shouldn't be readily visible. We keep the visual (auditory et cetera) domain empty and only give the cathartic release when we know it's earned. We summarize as:

2) Hide the castle a bit.

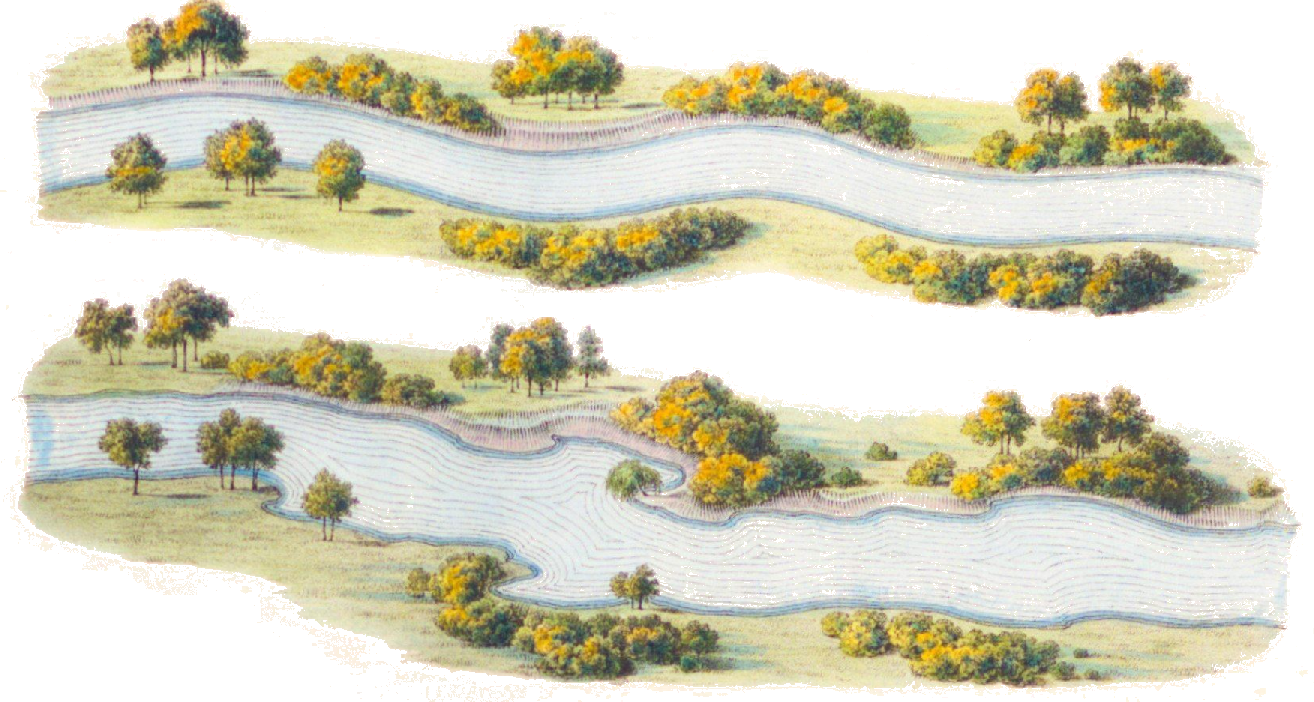

Another reason that parks are fundamentally awkward is that they imitate something they aren't. They want to be nature, but they are artifice. Pückler goes into significant detail describing observed patterns in trees and rivers in order to simulate them properly. For instance, a river will have a shallower edge on the inside of a curve than on the outside, because friction carves away at the dirt. The river on the top is boring and unnatural; the bottom one is interesting and natural:

Similarly, the clustering of trees should not immediately give away that they didn't plant themselves. The layout follows the principle of big, medium, small to accomplish that. Placing trees requires an understanding of what samples from a uniform distribution usually look like.

Architecture can also feel less or more natural. Where others liked to place decorative structures, Pückler insisted that buildings have a purpose instead of only looking like they have one. He writes:

„A Gothic house [...] that's only a Gothic house, standing there just because you wanted something Gothic, is uncanny and completely out of place. It's [...] impractical as a home and pointless as mere decoration, without any real connection to anything. [...I]t's not sufficiently justified. But if you see the towers of a Gothic chapel rising from the treetops on a distant mountain and learn that it's the family burial church or a real cult's temple, then you feel satisfied, because you encountered functionality."

At the risk of irritating his fellow Christians, the count installed a literal altar dedicated to the local heathen god Svantevit, simply because he wanted to connect the place to its history.  In his Hunter's Lodge, of course, there lived a hunter. Let's put one in our lodge, too. Emulation is sometimes easier than simulation. If emulation is not possible, we have a river on our hands, and we need to study it hard to do a good job simulating it.

In his Hunter's Lodge, of course, there lived a hunter. Let's put one in our lodge, too. Emulation is sometimes easier than simulation. If emulation is not possible, we have a river on our hands, and we need to study it hard to do a good job simulating it.

3) Emulate, don't simulate.

It would be great, wouldn't it, if the physical and digital environment we walked around in every day had such care put into it. Let's design away and bring the easy joy of Pückler's parks to our time as well.

.png)