Introduction

Individual and household actions to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions play a key and understated role in mitigating climate change. For example, household actions could contribute up to 40% of the projected total GHG emissions reductions incentivized by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), despite being supported by only 10% of the laws’ funding (Caballero et al., 2024). Choosing to purchase a new electric vehicle (EV) rather than a new combustion engine vehicle is one such individual action. Purchasing an EV in lieu of a traditional vehicle carries especially high technical potential, meaning that this consumer behavior could deliver substantial emissions reductions if adopted at scale, especially when compared with other one-time actions and investments (Dietz et al., 2009). Prior work highlights barriers to EV adoption including cost, limited charging infrastructure, and range anxiety (Egbue & Long, 2012). However, social and political factors including political polarization could also dissuade consumers from adopting EVs and other incentivized climate-mitigation actions (Burgess et al., 2024). Previous research has documented instances where people’s support for climate policy and their uptake of low-carbon or carbon-reducing household actions are affected by political identity cues–as to be expected when that action has become associated with one party or ideological orientation (Van Boven et al., 2018; Sintov et al., 2020).

There is reason to expect EV uptake to be sensitive to political identity cues. EVs’ symbolic attributes, such as their “eco-friendliness,” relative novelty, and association with science and academics (Sintov et al., 2020), align more closely with liberal than with conservative values and identities, and research indicates that alignment with a consumer good’s symbolic attributes is a strong predictor of a person’s attitude toward and ultimate intention to purchase the good (Orth and De Marchi, 2007). These symbolic associations have generated stereotypes about the types of people who drive EVs, which also have downstream effects for EV purchase intentions. These trends appear to have polarized U.S. public opinion toward EVs, with a reported 71% of Republicans unwilling to consider purchasing an EV compared with 17% of Democrats (Brenan, 2023).

Because the relationship between the two major U.S. political parties is itself polarized to the point of antagonism (Kalmoe and Mason, 2019; Iyengar et al., 2019), an association with a given party engenders positive attitudes in its members and negative attitudes in members of the opposing party. Negative attitudes are an especially potent driver of human behavior (Cacioppo and Berntson, 1994), often more than are positive ones. Positive and negative evaluative responses are driven by separate motivational systems, and the negative system responds more strongly than the positive system when evaluative input—that is, information that is relevant to positive-negative evaluation, such as political identity cues—increases. This effect occurs over a wide range of human behaviors, perceptual processes, and attitude domains, including person and brand perception (Norris et al., 2010), and is known collectively as negativity bias (Baumeister et al., 2001; Ito and Cacioppo, 2005). Once a negative association has been formed, it can be difficult to reverse its motivational effects (Cacioppo and Berntson, 1994).

However, developments in public perceptions of Tesla CEO Elon Musk raise questions about whether Tesla—one of the world’s largest EV manufacturers and the largest in the United States (Kelley Blue Book, 2024a, b, c, d)—might be more or less polarizing among U.S. adults than EVs in general. Musk’s public persona was initially one of scientist and entrepreneur, as evidenced by his portrayal in popular culture in the 2010s: He appeared in The Simpsons as a spacefaring inventor and businessman, where his motivation was explicitly stated to be saving the Earth rather than making money (Natsuk and Campbell, 2015); in the film Iron Man 2 (Favreau and Theroux, 2010), he appeared as a fictionalized version of himself, pitching an electric jet to the hero of the film, Iron Man; and in Star Trek: Discovery he was referenced as an historically great inventor, in the company of the Wright brothers (Osunsanmi, Alexander, and Coleite, 2017). He also broadly presented himself as either apolitical, once stating “I get involved in politics as little as possible,” in an interview (Vanity Fair, 2015), or liberal, as when he resigned from a business advisory position during the first Trump Administration when President Trump withdrew from the Paris Agreement on climate change (Breland, 2017).

After taking control of the social media platform X (formerly Twitter) in 2022, Musk initially made headlines for endorsing stances associated with conservatism or the Republican Party. For example, on June 15, 2022, he stated that he voted for Republican Congresswoman Maya Flores and that he was leaning towards voting for Republican Ron DeSantis for President (Musk, 2022a, b; Singh, 2022). Shortly before the November 2022 midterm elections, he urged “independent-minded voters” to vote for Republicans (Musk, 2022c; Heavey and Ayyub, 2022). He has frequently denounced what he refers to as the “woke mind virus,” a term commonly used by Republicans to refer to left-wing identity politics (Higgins, 2023). Perceptions of public figures are subject to such partisan influences, and these perceptions can sometimes shift quickly, as demonstrated in a December 2022 Quinnipiac poll finding that 63% of Republicans had a favorable view of Musk, compared to 9% of Democrats (Quinnipiac University, 2022).

This trend culminated in Musk’s public endorsement of Donald Trump for President in July 2024, after which he provided material assistance to the Trump campaign in the form of monetary contributions and public appearances with Trump on the campaign trail (Reid and Lange, 2024). Musk was then named head of the new Department of Governmental Efficiency, or DOGE, in the Trump administration. These public actions have resulted in a correspondingly strong public association between Musk and President Trump and the Republican Party more generally. For example, a January and February 2025 Pew Research poll found 73% of Republicans and those leaning Republican had a favorable view of Musk, compared to 12% of Democrats and those leaning Democrat (Pew Research, 2025).

These developing partisan cues may exert a strong influence on public consumer behavior. Research in social cognition indicates that positive-negative evaluations along two dimensions, warmth and competence, drive people’s perceptions of and subsequent behaviors toward others (Cuddy et al., 2008), including public figures and brands (Kervyn et al., 2022). Perceiving a business as trustworthy and likeable, which entails perceptions of high warmth and competence, is associated with higher brand loyalty and willingness to make repeat purchases from that business (Chaudhuri and Holbrook, 2001). People tend to make inferences about the character of a company through their assessment of its CEO (Kervyn et al., 2012)—a pattern that is especially pronounced for CEOs who frequently appear in the media (also called “superstar CEOs”; Malmendier and Tate, 2009), such as Musk. In addition to affecting the perceived trustworthiness of a brand, CEOs may impact purchasing behavior in the general public through appealing to or deviating from their social and political values. People are more likely to identify with a company they perceive as aligning with their values (Bhattacharya and Sen, 2003), especially for high ticket-price purchases (Torelli et al., 2012), making the CEO-company identity link especially important in predicting consumers’ purchase likelihood. Because partisan alignment signals both alignment in values and perceived trustworthiness more generally (Hernandez-Lagos and Minor, 2015; Cole et al., 2023), Musk’s increasing presence in the political sphere may be a strong signal to members of the public about his relative trustworthiness and alignment with their values.

Taken together, electric vehicles’ strong association with liberal values and Musk’s increasingly visible conservatism represent conflicting identity cues. On the one hand, electric vehicles are eco-friendly, associated with science and academics, and the new—all of which are strongly liberal-aligned symbolic attributes. On the other, Elon Musk is both the most prominent public figure associated with EVs for Americans and a close associate of Republican President Donald Trump’s administration (Pew Research, 2025). This implies differing possibilities for perceptions of EVs in the American public. Musk’s rightward turn may depolarize EVs, reducing the associations that drive conservatives’ negativity bias toward EVs and bringing their attitudes and purchase intentions in line with those of liberals. Conversely, these signals may activate liberals’ negativity bias and reduce their intentions to purchase Teslas or EVs in general. Alternatively, signals may be too new or isolated to change the highly polarized EV landscape.

The present study aims to test these possibilities directly, with five studies examining participants’ intention to purchase an EV as a function of their ideological identity. Study 1, conducted in August 2023, serves as our pilot study, establishing that there is a difference in EV intentions by ideology. Study 2, conducted in November 2023, introduces our primary experimental manipulation, randomly assigning participants to report their intention to purchase either a generic EV or a Tesla, specifically. In Study 3, conducted May 2024, we add a measure of perceptions of Elon Musk to directly examine the role of views on Musk in perceptions of EVs, with studies 4 (conducted in July 2024) and 5 (conducted in March 2025) serving as replications, allowing us to track how our patterns of results differ over time, as Musk’s political commitment to President Trump’s Administration, and subsequent solidified alignment with conservative identity in the eyes of the public, have developed. We also compare our results to relevant market and consumer data in the discussion section.

Methods

Participants and sampling procedure

Participants were recruited using Qualtrics Panels (Study 1, n = 654; Study 2, n = 551; Study 3, n = 500; Study 4, n = 513; Study 5, n = 710). Qualtrics panels primarily use nonprobability samples from actively managed, opt-in panels (Qualtrics, 2019), with respondents receiving incentives for completing a given survey. To ensure data quality, we excluded any respondents who finished the survey in less than half the median completion time, scored below a .5 on a reCAPTCHA check (which suggests bot activity), or overused item non-response (e.g., responded all “this does not apply to me/NA” for the behavioral intention measures described in the Materials subsection below). Any responses excluded based on these criteria were replaced by Qualtrics.

For all five studies, we also used quota sampling to bolster data quality. We recruited a nationally representative sample based on age and ethnicity, with target quotas on partisan identification (34% Republican (R), 30% Democrat (D), and 36% Independent (I) in Studies 2–4; 28% each R and D, 44% I in Study 5; Jones, 2025). We also set a gender quota in studies 2 through 5 (48% male and 52% female). We excluded participants who did not provide consent or their ideology from analysis, yielding final sample sizes of Study 1: n = 633, Study 2: n = 539, Study 3: n = 500, Study 4: n = 511, and Study 5: n = 689. Participants were paid a flat rate of $4 to complete a 10 minute study.

Across all studies, our sample included 56% women (44% men, <1% other), ranged in age from 18–95 years (M = 53.3, SD = 17.5), were predominantly White (71% identified as White, 4% Asian American, 11% Black, 8% Hispanic, 2% Native American, <1% Native Pacific Islander, 3% Other), reported partisanship in line with sample quotas (32% identified as Democrats, 31% Republicans, 37% Independents), and were moderate in self-reported ideology (9% identified as strongly liberal, 15% liberal, 40% moderate, 22% conservative, 14% strongly conservative). See the Supplementary Table S1 for full demographic information by study.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed the data with linear regression models, using contrast coded predictors for categorical variables. For studies 1 and 2, we measured ideology using a single item: “How would you describe your political views?” (−2 = Strongly liberal, 0 = Moderate, +2 = Strongly conservative). In studies 3, 4, and 5, we measured ideology using a 3-item scale, which included two items about how participants would describe their political attitudes on economic issues and social issues, in addition to the single item above (Study 3: α = 0.90, Study 4: α = 0.92, Study 5: α = 0.91). We use this continuous measure of ideology in the primary analyses. However, we graph the results of our models by binning this continuous variable for ease of visual comparison across studies: Participants with an ideology scale value less than −1.5 were classified as strong liberals, values between −1.5 and −0.5 were classified as liberals, values between −0.5 and 0.5 were classified as moderates, values between 0.5 and 1.5 were classified as conservatives, and values greater than 1.5 were classified as strong conservatives.

We constructed two sets of orthogonal contrast codes to conduct comparisons across studies. For comparisons using all five studies, we created four contrast codes that examine the linear, quadratic, cubic, and quartic effect of time. For comparisons of the studies that include perceptions of Elon Musk as a moderator—studies 3, 4, and 5—we created an orthogonal set of contrast codes: one that compares the average of studies 3 and 4 against Study 5 and one that compares Study 3 with Study 4. Because studies 3 and 4 were conducted within two months of one another while Study 5 was conducted eight months later, we felt this would be a more accurate examination of the linear effect of time than a code comparing Study 3 with Study 5 and a second code comparing the averages of studies 3 and 5 with Study 4.

Though political ideology was the political identity variable we selected for analysis in this paper (following similar research on the effects of political cues in polarized contexts; e.g., Malka and Lelkes, 2010), the effects reported throughout hold when using partisan identification (Democrat, Republican, and Independent) instead. These analyses are not reported in the main manuscript, but are included in the Supplementary Information (see Supplementary Table S2). The corresponding figures replicating Figs. 2, 3 from the main text using partisan identity are also included in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. S1 and Supplementary Fig. S2). All statistical tests reported in this manuscript and in the Supplementary Information are two-tailed tests of significance. All data were analyzed in RStudio (Version 2023.06.2; RStudio Team 2020).

Materials and procedure

Participants completed the study anonymously online using Qualtrics on a device of their choice. In all studies, respondents indicated their intentions to adopt each of 30 GHG emissions-reducing individual actions within the next five years on a 7-point scale (−3 = extremely unlikely, 3 = extremely likely). Respondents could also indicate that they were already doing this action or that the action did not apply to them; if they selected either of these responses for the question asking about intentions to purchase an electric vehicle, their responses were excluded from analyses (Study 1: n = 152, Study 2: n = 56, Study 3: n = 42, Study 4: n = 43, Study 5: n = 71).

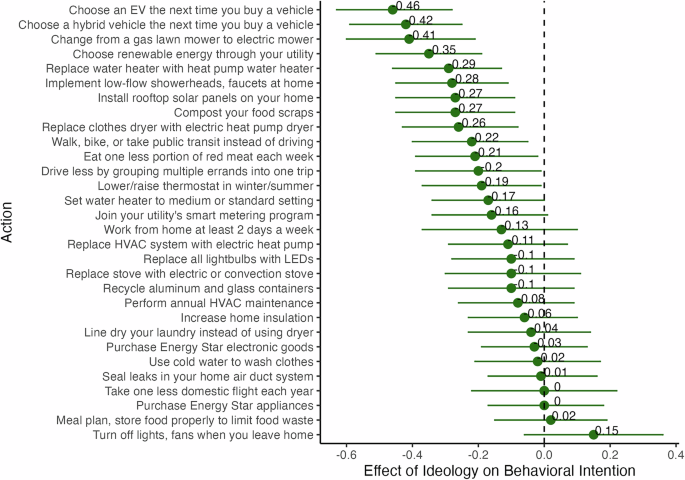

Our primary dependent variable was participants’ intention to purchase an electric vehicle (EV): “Please indicate how likely or unlikely you are to… choose [an electric vehicle/a Tesla] the next time you are ready to purchase or lease a vehicle.” In Study 1, participants were asked about their general EV purchase intentions, with no Tesla condition; starting in Study 2, they were randomly assigned to respond to either the generic EV or Tesla version of the item above. This action was presented in a random order among the other 29 actions; the effect of partisan identity on support for all actions evaluated is displayed below in Fig. 1.

Respondents were also randomly assigned to read these actions as actions to “reduce pollution or improve energy security” or to “reduce pollution, decrease greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change, or improve energy security;” this manipulation did not result in significant differences in intention to purchase an electric vehicle in any study (all p’s > 0.2) and is excluded from discussion.

In studies 3, 4, and 5, we measured respondents’ perceptions of Elon Musk using a 4-item measure: “For each of the following traits, how well do you think they describe Elon Musk?” The four traits were “likeable” and “trustworthy” (capturing the warmth dimension of person perception) and “competent” and “intelligent” (capturing the competence dimension), with responses measured on a 5-point scale (1 = not well at all to 5 = extremely well). Respondents could also indicate that they had not heard of Elon Musk, in which case their responses were excluded from analyses involving Musk perceptions (Study 3: n = 38, Study 4: n = 56, Study 5: n = 61). The measure reached acceptable reliability in all three studies (Study 3: α = 0.86, Study 4: α = 0.87, Study 5: α = 0.92).

After completing the main experimental measures, participants provided their partisan identification using a two-step procedure from the American National Election Studies (2021). Participants first indicate whether they usually think of themselves as a Republican, Democrat, or another partisan identity. If they select either Republican or Democrat, they then indicate whether they are a strong or not very strong member of that party; if they select any other option, they are asked whether they are closer to the Republican Party, the Democratic Party, or neither. Finally, participants provided socio-demographic information including race and ethnicity, gender, age, and household income before being debriefed.

Participants in all studies also answered questions about their beliefs related to the construct of personal responsibility for another study. The wording of all questionnaire items and their response options can be found in the Supplementary Information, Supplementary Text 1.

Results

Age, income, and gender are included in all models as controls. See Table 1 below for these effects by study.

Electric vehicle adoption is politically polarized

Study 1 was conducted in August 2023 with a sample of n = 633 U.S. adults. We measured respondents’ intentions to adopt each of 30 individual actions within the next five years that could reduce GHG emissions. Among the actions we tested, we found EVs to have the largest gap in behavioral intentions between conservatives and liberals (Fig. 1; see Supplementary Section 1 for analysis of behavioral intentions across all five studies), providing evidence for our basic premise: EV purchase intentions are politically polarized in the U.S. public. Intentions to purchase an EV was negatively associated with conservatism (b = −0.41, F(1, 449) = 20.28, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.043; Fig. 1); for respondents at the strongly liberal level of ideology, intentions to purchase an EV were positive (b = 0.57, F(1, 449) = 6.15, p = 0.014, ηp2 = 0.014), while for strongly conservative respondents, intentions were negative (b = −1.05, F(1, 449) = 29.33, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.061).

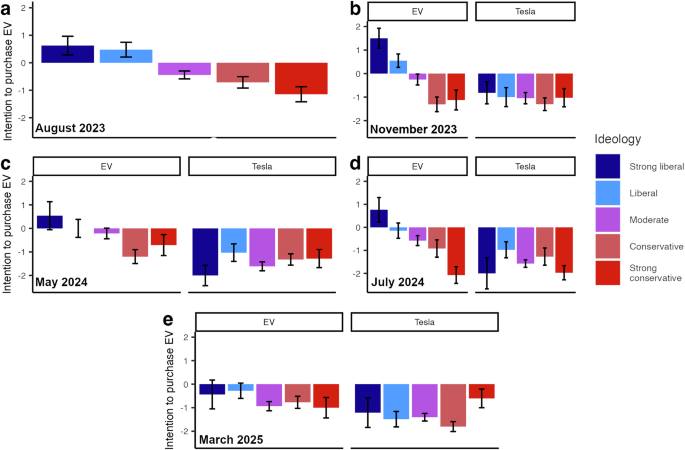

Liberals are less willing to buy Teslas than other electric vehicles

In Study 2, we again found that intentions to purchase an EV (across conditions) were significantly associated with linear political ideology, such that purchase intentions decreased as respondents’ conservatism increased (b = −0.37, F(1, 457) = 18.72, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.039). However, this effect is qualified by a two-way interaction with EV condition (b = 0.67, F(1, 457) = 15.62, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.033), illustrated in Fig. 2b. In the control condition, there was a strong effect of linear ideology (b = −0.71, F(1, 457) = 34.05, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.069) that replicates the finding from our first study; for respondents at the strongly liberal level of ideology, intentions to purchase an EV were strongly positive (b = 1.25, F(1, 457) = 18.21, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.038), while for strongly conservative respondents, intentions were negative (b = −1.58, F(1, 457) = 35.74, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.073), with moderates falling at the neutral midpoint (b = −0.17, p = 0.22). In the Tesla condition, there was no effect of ideology (p = 0.54). All respondents, regardless of political ideology, reported being unlikely to purchase a Tesla in the next five years (b = −1.12, F(1, 457) = 65.25, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.125).

Perceptions of Elon Musk predict respondents’ willingness to purchase Teslas and EVs

In Study 3, we again found a negative effect of ideology on EV purchase intentions across EV condition (b = −0.18, F(1, 449) = 4.39, p = 0.037, ηp2 = 0.010), such that willingness to purchase an EV decreased as conservatism increased. Intentions to purchase electric vehicles were overall negative when collapsing across political ideology and EV condition (b = −0.90, F(1, 449) = 94.09, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.173). We also replicated the interaction between ideology and EV condition (b = 0.39, F(1, 449) = 5.31, p = 0.022, ηp2 = 0.012), illustrated in Fig. 2c. This interaction was again driven by a negative effect of ideology in the control condition (b = −0.37, F(1, 449) = 8.50, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.019), with no effect of ideology in the Tesla condition (p = 0.89). Again, all respondents reported being unlikely to purchase a Tesla in the next five years (b = −1.39, F(1, 449) = 121.18, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.213).

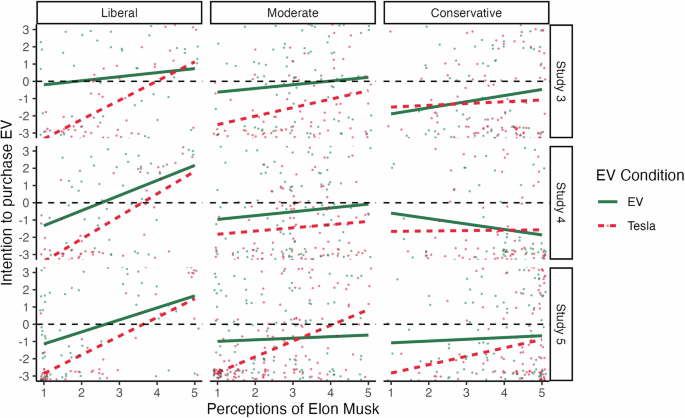

We found that perceptions of Elon Musk, collapsing across ideology and EV condition, positively predict EV purchase intentions (b = −0.34, F(1, 409) = 15.23, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.036). We also found a relationship between Musk perceptions and the interaction of ideology and EV condition: At one standard deviation below mean Musk perceptions, the ideology by condition interaction was positive (b = 0.55, F(1, 409) = 4.86, p = 0.028, ηp2 = 0.012), such that there was no effect of ideology on EV purchase intentions in the Tesla condition but a negative effect in the control condition; at mean levels of Musk perceptions, the interaction was attenuated to marginal significance (b = 0.31, F(1, 409) = 3.02, p = 0.083, ηp2 = 0.007); and at one standard deviation above mean Musk perceptions, it was no longer significant (p = 0.77). These differences in the ideology by EV condition interaction across levels of Musk perceptions were observed despite a nonsignificant three-way interaction in the context of the full model (b = −0.21, F(1, 409) = 2.14, p = 0.145, ηp2 = 0.005). The relationship between participant ideology, EV condition, Musk perceptions, and EV purchase intention for Study 3 is displayed in Fig. 3, top panel, below, and perceptions of Elon Musk by ideological identity for studies 3, 4, and 5 are displayed in Table 2.

Individual observations are represented by dots, color-coded by EV condition. The left pane shows the interaction effect for strong liberal and liberal respondents together, the middle pane shows the interaction for moderate respondents, and the right pane shows the interaction for conservative and strong conservative respondents together.

Study 4 partially replicated these findings. Again, we found a negative effect of ideology on EV purchase intentions across EV condition (b = −0.31, F(1, 459) = 11.96, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.025), with intention to purchase an EV decreasing as conservatism increases. Intentions to purchase electric vehicles were overall negative when collapsing across political ideology and EV condition (b = −1.03, F(1, 459) = 122.46, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.211). We also replicated the interaction between ideology and EV condition (b = 0.62, F(1, 459) = 12.03, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.026), illustrated in Fig. 2. This interaction was again driven by a strong negative effect of ideology in the control condition (b = −0.62, F(1, 459) = 22.94, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.048), with no effect of ideology in the Tesla condition (p = 0.99). Again, all respondents, regardless of ideology, reported being unlikely to purchase a Tesla in the next five years (b = −1.50, F(1, 459) = 132.43, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.224).

Musk perceptions positively predicted EV purchase intentions, collapsing across ideology and EV condition (b = 0.30, F(1, 406) = 10.61, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.025), as in Study 3. However, in Study 4 this effect was qualified by a two-way interaction between ideology and Musk perceptions, such that the EV purchase intention-Musk perceptions link decreases in strength as participants’ conservatism increases (b = −0.30, F(1, 406) = 12.27, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.029). Collapsing across EV condition, strongly liberal participants’ Musk perceptions were positively predictive of EV purchase intention (b = 0.90, F(1, 406) = 20.22, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.047), while at the strongly conservative ideological level, Musk perceptions were no longer predictive of EV purchase intention (b = −0.30, p = 0.12). These patterns were consistent in both the Tesla and EV conditions: for strongly liberal participants, Musk perceptions were positively predictive of EV purchase intentions (b = 0.69, F(1, 406) = 5.18, p = 0.023, ηp2 = 0.013) and Tesla purchase intentions (b = 1.12, F(1, 406) = 19.67, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.046), while for strongly conservative participants, Musk perceptions were not significantly associated with EV (p = 0.25) or Tesla (p = 0.27) purchase intentions. This supports the notion that perceptions of Elon Musk are beginning to affect perceptions of both Teslas and non-Tesla EVs among more liberal participants, while not providing an analogous boost among conservative participants. This relationship is shown in Fig. 3, middle panel.

Liberals decreasingly willing to purchase EVs, Teslas

In Study 5, political ideology predicted EV purchase intention as in the first four studies, such that increased conservatism was associated with lower purchase intentions (b = −0.22, F(1, 548) = 4.89, p = 0.027, ηp2 = 0.009) and respondents’ overall intention to purchase an EV, collapsing across EV condition, ideology, and controlling for Musk perceptions, was negative (b = −1.02, F(1, 548) = 120.56, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.180). In a departure from previous studies, the interaction effect of political ideology by EV condition on EV purchase intention was nonsignificant (p = 0.56). However, the EV condition effect itself was significant, indicating that participants again had lower purchase intentions for Teslas compared with EVs in general (b = −0.57, F(1, 548) = 9.46, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.017), collapsing across ideology.

The two-way interaction of Musk perceptions with ideology is nonsignificant (p = 0.057), while the interaction of Musk perceptions with EV condition is positive (b = 0.40, F(1, 548) = 8.33, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.015). For participants with low Musk perceptions (i.e., 1 SD below the mean), the EV condition difference is highly significant, such that intentions to purchase a Tesla are lower than general EV purchase intentions (b = −1.13, F(1, 548) = 20.84, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.037) and the effect of ideology is nonsignificant (p = 0.21). For participants with high Musk perceptions (i.e., 1 SD above the mean), the EV condition difference is nonsignificant (p = 0.99) but the effect of ideology is significant and negative, such that conservatives are lower in EV intention than liberals, collapsing across EV condition (b = −0.26, F(1, 548) = 4.86, p = 0.028, ηp2 = 0.009). These patterns are illustrated above in Fig. 3, bottom panel.

Liberals’ but not conservatives’ perceptions of Musk are associated with decline in EV, Tesla purchase intention over time

Across all five studies, overall intention to purchase an EV decreased over time (b = −0.67, F(1, 2422) = 57.09, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.023) while the relationship between ideology and EV purchase intentions became more positive over time (b = 0.29, F(1, 2423) = 11.94, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.005). In other words, while overall EV purchase intentions decreased from August 2023 to March 2025, this was driven by a sharp decrease in EV purchase intentions for strongly liberal participants (b = −1.24, F(1, 2422) = 37.99, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.015) while strongly conservative participants’ purchase intentions did not differ as a function of time (p = 0.56).

Across the studies that include perceptions of Elon Musk as a moderator (studies 3, 4, and 5) we found an interaction between ideology, Musk perceptions, and linear time (studies 3 and 4 compared with Study 5; b = 0.16, F(1, 1369) = 4.43, p = 0.036, ηp2 = 0.003). This indicates that the tendency for liberals with lower opinions of Musk to have lower intentions to purchase EVs than liberals with higher opinions of Musk (Fig. 3) strengthened over time. This pattern was not observed for conservatives, whose perceptions of Musk were consistently less predictive of both Tesla and general EV purchase intentions.

Notably, the EV condition effects did not differ as a function of time. Controlling for change over time, there was an interaction between EV condition and ideology (b = 0.34, F(1, 1369) = 9.55, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.007) and another between EV condition and Musk perceptions (b = 0.31, F(1, 1369) = 10.77, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.008), such that the difference between EV and Tesla purchase intentions were smaller for more conservative and more Musk-positive participants, respectively. That these effects did not change from May 2024 to March 2025—the same time period where EV purchase intentions fell sharply in general, primarily among liberals—suggests that negativity toward Elon Musk and the Tesla brand was a driving force behind liberals’ decreasing intentions to purchase EVs.

Discussion

In this study, we examine political polarization in participants’ intention to adopt EVs in general as well as EVs compared with Teslas. Our finding that conservatives have generally lower intentions to adopt EVs relative to liberals (Figs. 1, 2) is consistent with other recent surveys (Sintov et al., 2020). However, we also found that both liberals and conservatives have negative intentions to purchase Teslas. Moreover, liberals’ disinterest in adopting Teslas was similar in magnitude to that of conservatives’ towards EVs in general (Fig. 2). In other words, among liberals, the Tesla brand appears to wipe out an affinity towards EVs.

Elon Musk’s conservative persona (Quinnipiac University (2022); Pew Research, 2025) may help to explain our results. We found that liberals with low and moderate opinions of Elon Musk have lower intentions to purchase Teslas than EVs, whereas liberals with high opinions of Elon Musk do not differ in their intentions to purchase Teslas and EVs (Fig. 3). Conservatives do not differ in their intentions to purchase Teslas compared with EVs, an effect that does not significantly vary with their perceptions of Elon Musk (Fig. 3). Our first three studies pre-date Elon Musk’s endorsement of Donald Trump for President, our fourth study was undergoing data collection as the endorsement occurred on July 26th, 2024, and our fifth study was completed after Musk had assumed his official role in the Trump administration. Thus, our results span a timeframe during which Musk’s public image became both symbolically more conservative and materially more closely associated with the conservative Republican Party.

In addition to the negative Tesla effect among liberals, these studies provide mounting evidence that liberals are becoming less positive toward EVs in general, a relationship that appears to be tied to their views of Elon Musk. In studies 3, 4, and 5, the overall support for EVs among participants across the strong to moderate liberal end of the ideological identity spectrum is lower than in the first two studies, a difference that is more pronounced at more negative perceptions of Musk. This “Tesla backlash effect” among liberals, paired with the indelible negativity bias displayed by conservatives toward both Teslas and EVs in general, carries important implications for how public perceptions of company leaders can shape both consumer attitudes and behavior toward not only their own brand but their entire industry. This may be especially important for leaders of green or eco-friendly brands and businesses, as impacts to the sustainability industry affect efforts to address climate change through GHG emissions reductions.

Our initial hypothesis was that Teslas might be more supported by conservatives than EVs, and therefore Teslas would be less polarizing than EVs overall. In contrast, we found conservative intentions to purchase Teslas and EVs were indistinguishable (Fig. 2). Teslas were less polarizing, but only because liberals reported substantially lower intentions to purchase Teslas. We advanced negativity bias as a potential reason conservatives might continue to hold relatively cool attitudes toward EVs—while we found evidence that this was the case for conservatives, we did not expect this same bias to affect liberals’ EV attitudes. But this is what our studies suggest: Our participants were more motivated to reject something over an aspect they dislike (the Musk-associated Tesla brand for liberals and the eco-friendliness of EVs for conservatives) than they were motivated to adopt something for an aspect they like (the fact that Teslas are EVs for liberals, or the Musk-associated Tesla brand for conservatives; Baumeister et al., 2001). For an analogous example, a recent survey experiment by Marshall et al. (2024) found that climate policies lose support from liberals when paired with pausing Environmental Protection Agency regulations, without gaining support from conservatives; while climate policies lose support from conservatives when paired with social justice policies, without gaining support from liberals.

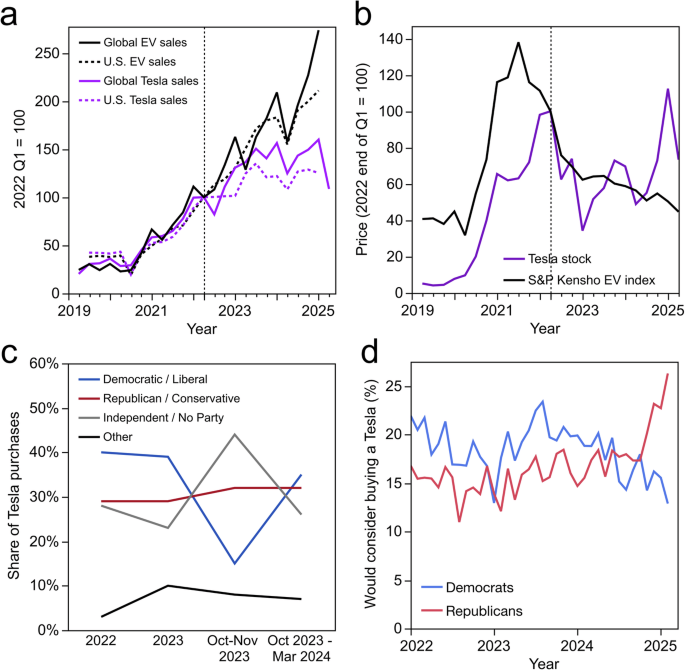

If our results suggest that Americans have a lower opinion of Tesla’s brand compared to EVs in general, the market signal of that may be emerging, albeit with some nuances. Figure 4a, b compares trends in Tesla’s sales and stock price to those of EVs in general, before and after the first quarter (Q1) of 2022, which ended shortly before Elon Musk’s April 14, 2022, bid to take over Twitter became public (Subin, 2022). EV sales as a whole have risen steadily since 2019, whereas Tesla’s global and U.S. sales have plateaued since mid-to-late 2023 (Fig. 4a). This could be a result of consumer responses to Musk’s and Tesla’s brands, though other factors such as competition from other major EV makers likely play a role as well. In contrast, Tesla’s stock price has fared better, on average since 2022 Q1, than the Standard & Poors (S&P) Kensho EV index (Standard and Poors S&P Global, 2025), which tracks the EV industry as a whole (Fig. 4b). Although Tesla’s stock price fell by more than 30% in the first quarter of 2025, these losses only erased large gains immediately following President Trump’s election in November 2024, which other EV companies did not realize.

a compares Tesla sales and all EV sales (in terms of units sold), in the United States (Kelley Blue Book 2020a, b, 2021a, b, c, d, 2022a, b, c, d, 2024a, b, c, d) and globally (International Energy Agency IEA (2024); Kane 2024a, b; Kolodny, 2025; Statista, 2025). b compares price trends in Tesla stock (Yahoo Finance, 2025) and the Standard & Poors (S&P) Kensho Electric Vehicles index (Standard and Poors S&P Global (2025)). Dashed lines in panels a and b denote the end of 2022 Quarter 1, when Elon Musk’s offer to purchase Twitter became public (Subin, 2022). c shows the shares of U.S. Tesla buyers having different political affiliations in Strategic Vision polls (Higgins, 2024). (Christopher Chaney from Strategic Vision clarified the reported numbers in a personal communication). d shows percentages of Democrats and Republicans willing to buy Teslas from a monthly series of Morning Consult polls reported in the Wall Street Journal (Peterson and McLain, 2025).

Beneath these aggregate data, there are also more fine-scale market data consistent with our findings. For example, Tesla’s shares of new vehicle registrations have fallen faster in Democrat-leaning U.S. counties than in Republican-leaning counties since Musk bought Twitter (Coy, 2024). A Strategic Vision poll found a declining share of Tesla purchases by Democrats and a rising share by Republicans from 2022 to 2024 (Fig. 4c; Higgins, 2024). A series of Morning Consult polls found a steady decline in self-reported willingness to buy a Tesla among Democrats since 2023, and a sharp increase among Republicans following President Trump’s election in 2024 (Fig. 4d; Peterson and McLain, 2025). In a recent Data for Progress poll for HeatMap news (Meyer, 2025), two-thirds of Democrats and half of Independents reported that Musk had made them less likely to buy a Tesla, whereas most (55%) Republicans reported that Musk had no impact on their intentions to buy Teslas, compared with 23% who reported Musk had made them more likely to buy Teslas. This asymmetry—whereby Democrats and Independents have been moved more negatively by Musk than Republicans have been moved positively—is consistent with our findings and with the notion of negativity bias.

While our experimental results are consistent with political factors swaying Americans’ perception of Teslas, other explanations are also possible. It may be that Americans perceive Teslas as luxury vehicles, and the negative shift in intention to purchase an EV was driven by practical rather than ideological factors. To assess this possibility, we entered participant income as a moderator rather than a control in the model assessing the effect of EV condition and ideology on purchase intention over time for all studies that include the EV condition manipulation. We found that, while income positively predicts intention to purchase an EV overall (b = 0.06, p < 0.001), it does not interact with participant ideology (p = 0.09), EV condition (p = 0.34), or time (p = 0.19).

Our results highlight the brand challenges that can result from executives visibly entering the political arena. Although our findings focus on one particular brand (Tesla), other brands likely face similar challenges. We do not intend for our results to serve as a normative commentary on the Tesla brand or on the merits of Elon Musk’s political views. Our results also highlight the possibility that negativity bias could limit public support for low-carbon brands, complementing similar results regarding support for climate policies (Marshall et al., 2024). In a complex and polarized American political landscape, this may be an important consideration for policymakers, entrepreneurs, and advocates hoping to address climate change.

.png)