This is the back half of the third part of our series (I, II, IIIa) discussing the patterns of life for the pre-modern peasants who made up the great majority of humans who lived in the past. Last week, we started looking at family formation through the lens of marriage, this week we’ll consider it through the lens of children. While contra the schoolyard rhyme, we’ve seen that love coming first wasn’t generally thought to be a requirement, “then comes marriage, then comes baby” mostly was.

Our model for childrearing comes here because it is going to build on the assumptions we’ve already laid out about the mortality structure (very high infant and child mortality, elevated maternal mortality) and marriage patterns. What we’re going to see is that for a population to remain stable or slowly growing required, under these circumstances, quite a births, but at the same time not the maximum number of births. While we sometimes see elite populations drop birthrates below replacement, the pressures on the peasantry were different: having many children was a status-enhancing thing and children could provide valuable household labor. At the same time, because access to productive resources (especially land) was limited for such peasants, there was absolutely such as a thing as too many children. Consequently, peasant reproductive strategies are about staying within a range, but of course in the context of higher cost, higher risk or less reliable methods of birth control.

All that said, before we go any further, fair warning: this post is going to discuss how babies are made and also procedures used in history to prevent the making of babies (and do so quite frankly) and as a result may not be everyone’s idea of ‘appropriate for all ages.’ We’re also going to be talking about pregnancies, miscarriages, stillbirths and maternal mortality and I know that is a very emotional topic for a great many people. The analysis here is going to be, at times, quite emotionally ‘flat,’ but I hope no one takes that as indifference to the great joys and deep sorrows that come with the process of pregnancy, now and in the past.

Another obligatory note before we dive in: we’re going to be discussing pre-modern childbirth and fertility control here. I am, of course, not a doctor and while I have done my best to base the following off of sound medical (and historical) information, no one should be making health decisions on the basis of my blog posts and also do not get your medical practices from the pre-modern world, for reasons we have already amply discussed!

But first, if you like what you are reading, please share it and if you really like it, you can support this project on Patreon! While I do teach as the academic equivalent of a tenant farmer, tilling the Big Man’s classes, this project is my little plot of freeheld land which enables me to keep working as a writers and scholar. And if you want updates whenever a new post appears, you can click below for email updates or follow me on Twitter and Bluesky and (less frequently) Mastodon (@[email protected]) for updates when posts go live and my general musings; I have largely shifted over to Bluesky (I maintain some de minimis presence on Twitter), given that it has become a much better place for historical discussion than Twitter.

Threading a Needle

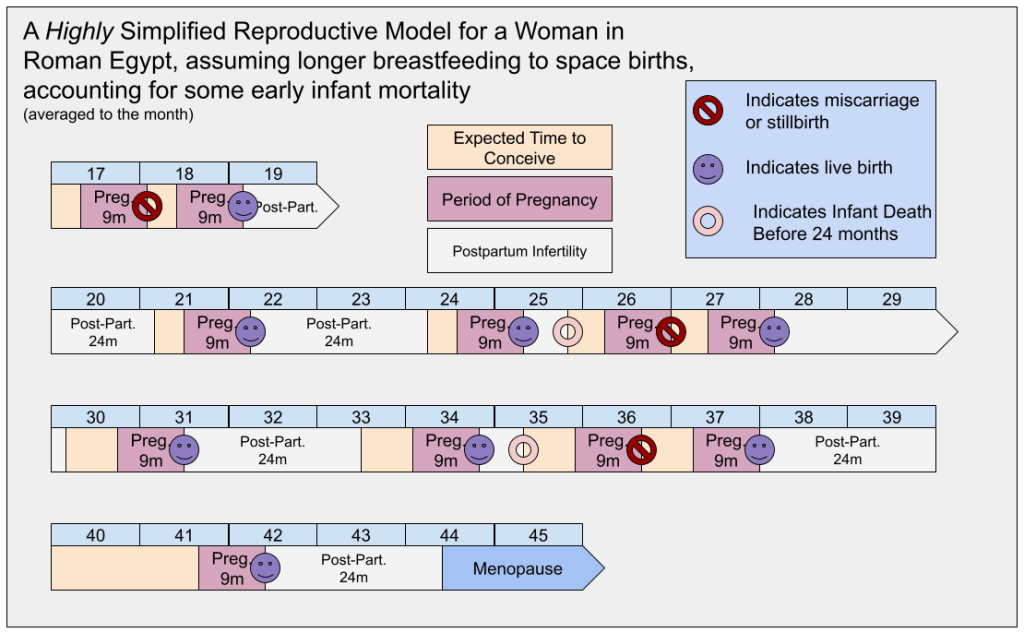

We can start with modeling a slow-growing population to understand some of the concerns here. As we’ve seen already, there can be some significant variation in marriage patterns and (within bounds) mortality patterns which are going to impact the final numbers, so for the sake of consistency, we’re going to use the data we have for Roman Egypt – our best for antiquity – for mortality and nuptiality. That means a mortality pattern following a Model West L3 (child mortality around 55%, on the high end for the pre-modern) and an average female AAFM around 17 or 18. As we’re going to see, under these assumptions, the conundrum the peasant family finds themselves in is two-fold: on the one hand, they need to have a lot of pregnancies to achieve stable replacement or slow growth, but on the other hand, they still need to suppress normal ‘maximum’ fertility to avoid unsustainable household growth.

To explain what I mean, let’s consider what an approach seeking to maximize children might look like under the above conditions. Now we have a few more variables to introduce here. First, of course, pregnancies do not just happen on command and the chance of becoming pregnant declines as a woman ages: the chance for a couple trying for a baby to conceive is 85% per year for a mother under 30, 75% at 30, 66% at 35 and 44% by 40. Taking one set of per-month odds from the American Society of Reproductive Medicine, we can calculate a very simple average expected interval, which if I am doing my math correctly is an expected value calculation: from 17 (AAFM) to 25 we might assume a 25% chance per month (expected interval of four months), from 26 to 30 a 20% chance per month (expected interval of five months), from 31 to 35 a 15% per month chance (excepted interval of 6.66 months; we’ll round to seven) and from 36 on up a 5% chance (expected interval of 20 months), until menopause, which came earlier in antiquity than in modern western countries, generally between 40 and 45, rather than 45 and 55. That’s obviously a very simplified model of fertility, but it will serve to demonstrate some basic principles.

Next, we need to consider of course that a woman is not always able to conceive (even if she has no fertility problems) because of course already pregnant women cannot conceive. In addition, mothers who are breastfeeding have sharply reduced fertility (‘lactational amenorrhea‘ or ‘postpartum infertility’). That matters quite a lot for our peasants because they live in a world with no baby formula and thus no easy alternatives to breastfeeding, but are too poor to afford the wet nurses of the elites. There is a lot of variation, both individual and cultural, in how long this period lasts, but for simplicity’s sake, we can assume something like a year after successful live birth while breastfeeding continues.

Via Wikimedia, a Roman mother nursing an infant, a detail from the sarcophagus of a young boy (c. 150 CE) now in the Louvre (CP 6547; Ma 659).

Via Wikimedia, a Roman mother nursing an infant, a detail from the sarcophagus of a young boy (c. 150 CE) now in the Louvre (CP 6547; Ma 659).Finally, we have to consider the miscarriage rate. Estimates for miscarriage rates I’ve found vary massively from 10% to as much as 33%; it seems like the more responsible estimates are in the 10-20% range. Given weaker nutrition, higher disease rates and so on, we’d expect the ancient miscarriage rate – which I don’t know that we can estimate with any precision – to be on the high end. Combined with the stillbirth rate, we might assume something like one in four (25%) of pregnancies end without a live birth.

If we were doing a full study, we’d take all of those variables (in rather more sophisticated form) and run a bunch of computer simulations to generate averages, but this is a blog post, so instead I am going to take a bit of a shortcut and just generate a single ‘model’ mother, who is maximizing the number of her children. We’ll assume every fourth pregnancy, beginning with the first, fails to result in a live birth (and thus no period of lactational amenorrhea). I want to stress, we’re not modeling here a ‘typical’ woman’s reproductive life-cycle, but instead probing what maximum fertility looks like; as we’ll see, this is not typical! What we get is a very rough model that looks like this:

There are some immediate necessary caveats: of course this is a highly simplified model, not a statistical average. It doesn’t account for low probability events like maternal mortality and obviously the regular spacing of pregnancies and miscarriages is also a simplification. I should also note that I’ve opted to assume a full nine month period for pregnancies here ending in miscarriage, but of course most miscarriages happen in the first trimester and fertility after miscarriage generally returns very quickly, so in most cases the interval here would be shorter. I suspect there are substantial refinements to be had in nearly all aspects of the model, but the point was to make a very rough estimate, which we may now do.

Our model Egyptian woman, married at 17, experiences nine live births and four (or three, depending on when menopause arrives) miscarriages. With nine live births and a 55% child mortality rate, 4.05 of those children survive to adulthood. That implies a net reproductive rate (NRR, the number of daughters who reach adulthood born to each woman who reaches adulthood) of two, which implies a population that would grow very rapidly, indeed far more rapidly that our evidence allows or than peasant economies could support. Instead, as Bruce Frier notes, the observed population trends we see in antiquity, combined with our estimates of child mortality, implies five to six live births per woman, not nine, to get an NRR just barely over 1 instead of 2.

Now your average peasant couple isn’t directly considering the impact their child-bearing patterns will have on our archaeological evidence for population change, of course. They’re considering their desire to have another child, which in a society where children brought a lot of social status, was often going to be a decision about their ability to support another child. But the impact is the same: the peasant wife (and her husband) had to thread a fertility needle between high child mortality (requiring a high birth rate) and high natural fertility (which would push the birth rate even higher than that), aiming to land somewhere close to population replacement with a little bit of growth.

What the model above thus strongly implies is that the absence of runaway population growth we see in our evidence requires our peasant families to be engaging in some degree of ‘family planning.’ Which brings us to:

From the Science Museum, London, a marble plaque showing a Roman birthing scene, excavated at Ostia, date uncertain.

From the Science Museum, London, a marble plaque showing a Roman birthing scene, excavated at Ostia, date uncertain.Birth Control Strategies

Now its important to clarify a misconception here at the beginning that ‘people in the past didn’t have birth control.’ What we mean is that they didn’t have highly effective (pharmaceutical) and very safe birth control. That, of course, matters a lot if someone wants to be sexually active and their acceptable number of pregnancies is zero: they want a birth control solution which is extremely effective and also very low risk. But for someone whose acceptable number of pregnancies is not zero (but also not ‘all of them’) suddenly a lot of lower effectiveness strategies become viable to space out rather than entirely eliminate pregnancies.

The most immediate such strategy is, of course, “delay marriage” by which we mean “delay the onset of becoming sexually active” in societies where sexual activity outside of marriage – for women, at least – was sharply condemned. This is very obviously part of what is happening with the late/late western European marriage pattern and on some level it seems like it can’t be an accident that pattern is emerging in a Christian cultural context where there is both some significant disapproval of other methods of birth or family-size control and probably lower rates of mortality (meaning the ‘target’ birth rate is coming down too).

Beyond this, at least in the Roman context, the job of fertility control, to the degree it was practiced, seems to have fallen on women. A variety of strategies were available. ‘Fertility awareness‘ strategies have regular use failure rates that are a lot too high for most modern folks to consider them a fully reliable strategy to achieve zero pregnancies, but as a strategy for spacing out and and thus limiting the total number of pregnancies, it could bring down the average significantly. The ancients seem aware of this strategy, (e.g. Augustine, On the Morals of the Manichaeans 18.65) but it isn’t clear that medical writers had the correct timings, though I rather suspect that knowledge among women on this point, passed down informally over generations, may have been better than what we see from the elite male authors of ancient medical treatises.

Beyond this, of course, methods of sex beyond vaginal intercourse could also be used to avoid or limit pregnancies. Sue Blundell notes that when Greek artwork depicts heterosexual sex, it is often oral or anal and even points to lines in Aristophanes (Wealth, 149-52) with prostitutes in Corinth showing their anuses to potential customers. Likewise, coitus interruptus (the ‘pull out’) method seems to have been understood (though Greek medical writers like Soranus suggest it is the woman who ought to back off, because, again, the responsibility for birth control was placed on women in Greek culture). Women might also employ pessaries of various herbs in an effort to disrupt the sperm or otherwise hinder fertility; some of the substances mentioned in antiquity seem like they would have at least some effect. Physical barriers may also have been used, but our evidence for things like condoms only becomes clear in the early modern period, though the basic notion that blocking or expelling semen would prevent pregnancy appears in antiquity.

In addition, a wide array of abortive practices, ranging in safety (though generally not very safe) and effectiveness were known since antiquity. For Greek and Roman antiquity, a lot of attention is given to the contraceptive usage of silphium (a now extinct plant with contraceptive and abortifacient properties), but other abortifacient plants like hellebore, birthwort or pennyroyal were available – the downside in basically all cases is that the plants are quite toxic so the risk is considerable. Likewise, from antiquity methods and instruments to perform something like a dilation and evacuation procedure existed, but the risks must have been substantial.

From the British Museum (D,5.59) a print of a Dutch engraving showing a mother nursing her child (1655-1677). For children, particularly girls, growing up in a pre-modern (or early modern) peasant community, these sorts of ‘facts of life’ of parenting would have been very visible, indeed they could hardly have been concealed.

From the British Museum (D,5.59) a print of a Dutch engraving showing a mother nursing her child (1655-1677). For children, particularly girls, growing up in a pre-modern (or early modern) peasant community, these sorts of ‘facts of life’ of parenting would have been very visible, indeed they could hardly have been concealed.In addition, a wider spacing of pregnancies could also be achieved by prolonging breastfeeding and thus extending lactational amenorrhea. The medical risk of pregnancies in too rapid a sequence seems to have been understood in antiquity, so this sort of ‘spacing’ technique would have made sense. Soranus (Gyn. 2.47) recommends weaning only at eighteen to twenty four months, which also matches preserved wet nursing contracts from Egypt.

Finally, many societies practiced infant exposure or other forms of infanticide. Both Greek and Roman sources report the practice for unwanted babies or those thought to be deformed and Roman law gave the pater familias the authority to order the death of his child. Infanticide in medieval Europe was strongly discouraged, although the harshest punishments for it emerge only in the 15th century. Alternately, infants might be left in a public place either to perish or to be fostered by another family; many pre-modern societies had customary locations for such infant abandonment. In the Greek and Roman world, such abandoned infants could also be enslaved. That said it is hard to know how common such practices were even in societies where they were known. As noted, infanticide and infant exposure were both entirely legal in the Roman world (albeit often disapproved of by our literary sources), but while the literary evidence suggests female newborns were more likely to be unwanted than male newborns, if there was any effect on the sex ratio (as seen today in countries where the practice of sex-selective abortion is common) we can’t see it in our admittedly limited evidence. Likewise, our literary sources often seem to suggest that disabled or deformed infants were invariably killed in Greece and Rome, but more recent scholarship, particularly by Debby Sneed, suggests this was not always the case and that disabled Greeks and Romans were more common than once thought.

That said, we also want to note the impact of both infanticide and also exposure-and-fostering has on a demographic model of population growth, which is that it doesn’t – of course this is quite apart from the emotional and moral considerations. Of course an infant which is exposed and either fostered or enslaved does not disappear from the demographic model, but rather simply grows up in another household. But also remember that when we model the populations of ancient or medieval societies until quite late, we do not have a record of the number of live births: we are back computing those figures from population snapshots created in our evidence. In those circumstances, infanticide is statistically indistinguishable from other forms of infant mortality – we have no way of separately quantifying the two – and so the rates of infanticide in these societies, whatever they may have been (they were certainly not zero) are already ‘baked in’ to our models.

Given all those methods in mind, we can go back to our model and nuance it a bit. Below I’ve charted out what the model looks like if breastfeeding is extended to 24 months and lactational infertility holds for all of those 24 months (it doesn’t always, but these are simplifying assumption). It brings down our expected live births down to seven (given how late the last one falls, we might say six-and-some-percent; remember menopause seems to occur earlier in societies with more limited medicine and nutrition).

But extending lactational infertility so long puts a lot of strain on one of our other key assumptions, which is that we’ve assumed full breastfeeding time for each child, but on our model life tables (again, Model West, L3), fully one third of children never reach their first birthday. The premature death of a child is, of course, going to end lactational infertility early. So here is a revised version of the model now assuming one out of every three live births results in a child that only lives six months – again, not a very rigorous model but a rough effort to get a sense of the impact this has (note that we’re still assuming child mortality around 50%, but only accounting for the c. 33% that perish within the first year).

That moves the model back to eight live births over a lifetime, though once again given how late the last live birth falls, we probably ought to say seven-and-some-percentage. Finally, we ought to account for mortality. To do this very roughly, we can go back to our Model West L3 life table, which breaks mortality into five year brackets, check what percentage of our cohort of mothers dies in each bracket and assign that percentage the number of births they’d have by that age in our chart above and, assuming I’ve done my math right, we land at an average number of live births per woman of 6.684, which is still a bit high of our expected replacement-and-a-bit-more (which should be around 5.8 for a slowly growing population under these mortality conditions). So to have observed population patterns, we still need births spaced out a bit more than this.

I should also note that this model is another reason why I find ‘intermediate’ female AAFM models (so AAFM between 17 and 20 or so, ‘late teens’) at least plausible for ancient societies. Even moving the AAFM here from 17 to twenty doesn’t push our model below replacement – it effectively subtracts one live birth from every age bracket in the sample, which after all the mortality calculations gives us an average of 5.68 live births per woman or a gross reproductive rate of 2.84, very close to the GRR of 2.9 Bruce Frier supposes necessary for a population growing at 0.5% per year, roughly what we suppose to have been typical in antiquity. Consequently, a Roman female AAFM of 18 or 19 doesn’t strike me as inherently unreasonable (though clearly with our ancient mortality assumptions, one cannot push over 20 – mortality has to be lower to make the late/late marriage pattern viable).

The point of all of that modeling is that despite the high child mortality peasant families who want manageable levels of fertility (which would be slow population growth in the aggregate, but they’re not concerned about the aggregate) have to engage in a meaningful amount of fertility control (beyond any infanticide or exposure, which is, again, baked into our infant mortality estimates). The precise mix of methods and techniques is going to vary by culture and region and we are able to glimpse these only very imperfectly, but we can be sure some degree of fertility control was always going on because we don’t see the sort of runaway population expansion implied by a maximum fertility model. Instead, given the high mortality estimates we laid out in part II, we would expect around five or six live births per woman, rather than the c. nine implied by a maximum fertility model. If we were to tweak the variables of our mortality regime (generally downward), we would also be lowering the expected number of births, something that may in part explain the late/late early modern European marriage pattern.

Paternity

Cultural attitudes in pre-modern societies towards parenthood and children varied a fair bit, but I want to cover some recurrent features here.

The first pattern is typically (but not quite universally) a strong concern and substantial anxiety over paternity and indeed one might argue that when our (elite, male) literary sources repeatedly stress the purpose of marriage is the production of (legitimate) children, one might well argue the true purpose was to establish secure paternity for children. Of course, some anxiety about paternity is common even in modern societies: mothers can be quite sure about their maternity, but absent medical testing, a father might doubt.

But this question matters much more in a society where nearly all wealth comes in the form of scarce farmland that is inherited from one generation to another and overwhelmingly if not entirely owned by men – even in societies like Rome where women could hold and pass down property, most of the landed wealth passed down the male line. Social status in these societies is essentially predicated on land ownership, without that farm the social position of even the peasant functionally collapses and given the extremely low social mobility in these societies, it collapses with little if any chance to ever regain it. Consequently, as you might imagine, the men who dominate these patriarchal societies are extremely anxious that their holdings – their position in society, however meager, which grants them a more-or-less stable living – pass to their actual, biological descendants.

This is a substantial viewpoint shift, so I do want to stress it: we live in a society where wealth is produced in substantial quantity daily and new economic niches emerge in the tens and hundreds of thousands every month. But for peasant farmers, the amount of wealth and the number of economic niches was, if not fixed, growing only very slowly so the careful preservation and inheritance of the limited and basically fixed supply of economic and social niches which ensured respectability and survival was of far greater importance.

Placing those concerns in the context of a society which could not text for paternity, dominated by men for whom that anxiety was so central, and much of what follows makes sense. Most pre-modern societies had a double-standard on sexual activity: penalties for promiscuity for women who were married or marriageable (by ‘marriageable’ I mean a woman of the respectability, age and social standing that she might be married) – that is, women whose children might be in a position to inherit, whose paternity mattered – were very harsh. For women outside of that world (sex workers, for instance), penalties might be much less harsh, amounting to not much more than permanent exclusion from the world of marriageability from which they were already excluded. Meanwhile for men, promiscuity might in some contexts be disapproved of (lightly so in Rome, more seriously so in much of medieval Europe, but not much at all in ancient Greece; I can’t speak well to other regions and periods), but it was generally permitted so long as it did not implicate the chastity of married or marriageable women.

That final point is something often misunderstood about these societies, where students – and even, to my frustration, sometimes teachers and public communicators – might assume that, say, in a case of adultery (understood by many of these cultures to be illicit sex with a married woman; the married status of the male does not matter) that the woman was punished but the man was let off, which is very much not the case. In Athenian law, for instance, it was legal to extra-judicially murder a man engaged in adultery with your wife. Under the Lex julia de adulteriis coercendis (The Julian Law On the Suppression of Adultery), wives who committed adultery lost half their property and were banished but so were their partners in adultery (banished to different remote islands, under the law).

In short, the adultery double-standard in many of these societies is that adultery law was primarily concerned with the secure parentage of children in a marriage and so cared quite a lot less about a married man having sex outside of marriage so long as it was not with another married or marriageable woman. Instead, adultery was the crime of illicit sex with a married woman, not a married person. Some societies also had laws against illicit sexual acts outside of marriage – in Roman law this was stuprum – which often carried lesser penalties.

The intensity of that anxiety could also have impacts on women’s lives – controlled, as they were, by a male-dominated patriarchal social order – although this varies a fair bit by culture. In some places, ‘respectable’ elite women might be ‘cloistered’ – that is, made to live in relative seclusion – though this could hardly have been an option available to most peasants. Still, women’s social access to men and male spaces might be sharply restricted – we see plenty of such restrictions in Classical Athens, for instance. But it was not always the case and here Rome provides the counter-example: respectable women, even elite Roman women, moved through Roman society, frequented public places and the Roman banquet ritual (the cena) included women and children (in contrast to the all-male-save-for-entertainers Greek symposion). Nevertheless, while the Romans probably represent the most gender-liberal ancient society, the concern placed on female chastity was substantial and respectable women were expected to veil themselves in public as a sign of their modesty.

Motherhood and Childhood

As with paternity, of course there is more variation in rituals and habits around motherhood and childhood than we can cover here, but I want to point out some common elements.

To begin with, I think it is worth simply pointing out some of the obvious logistics of motherhood here. If the average woman has roughly six live births over her lifetime in order for a population to replace itself, that means – as you can see above – that a woman surviving to menopause needs a bit more than seven (to make up for early mortality in other mothers), which, accounting for miscarriages might mean something like 9 or 10 pregnancies over a lifetime.

Assuming a typical mother surviving to menopause has 9 pregnancies, under the assumptions of our model above, that out of the c. 25 (~300 months) years of her reproductive adult life, she would spend 81 months (27%) pregnant and another c. 121 months (40%) nursing. Now I want to be very clear: that doesn’t mean she was not working in those months, because as we’ll see, she absolutely was working on a wide range of essential tasks. But the demands on our peasant mother’s time are considerable.

Via Wikipedia, the ‘Tellus’ Panel of the Ara Pacis (13-9BC). The identity of the central goddess is the subject of debate, but the overall theme of prosperity and fertility, with the goddess as mother to twin children on her lap, is very clear and fitting with Augustus’ cultural program.

Via Wikipedia, the ‘Tellus’ Panel of the Ara Pacis (13-9BC). The identity of the central goddess is the subject of debate, but the overall theme of prosperity and fertility, with the goddess as mother to twin children on her lap, is very clear and fitting with Augustus’ cultural program.In functionally all pre-modern agrarian cultures, the demands of childrearing fell almost entirely on women: some of this was, of course, patriarchal gender roles, but quite a bit of this was the unavoidable impact of the nature of a society with high child mortality (so mothers would need to bear and nurse a larger number of children in order to ensure a given number survived to adulthood) combined with the absence of modern technologies like baby formula that let fathers perform some kinds of childrearing labor they would otherwise be incapable of. At the same time, it is not hard to see how the culture of gender-inequality is going to be shaped by these norms: so long as the baby is nursing (either because it must or because nursing is being extended to suppress unwanted fertility) its mother needs to be in physical proximity more or less continuously – in a society where ‘so long as the baby is nursing’ might be almost half of a woman’s reproductive life, that becomes a pretty major life-shaping concern.

Children, of course, do not stop needing parenting merely because they’re no longer nursing, but childhood in these societies was quite a bit shorter. Remember that these are societies which understand individuals primarily through their social roles, not as individuals per se and children were no exception. Thus, rather than a broad education preparing children for a wide range of possible life paths, children in peasant households were expected to slot into the same social and labor roles as their parents and began doing so pretty much as soon as they were physically able. Consequently, children in these households learned their tasks and roles by watching their parents and other family members perform them. Their labor was also important: these households could not afford to maintain children in idleness (or in pure focus on an education). We’ll talk about the typical gendering of labor roles in the household in the next part of this series, but those gender-divisions were introduced functionally immediately in childhood: girls began spinning thread at very young ages (essentially as soon as they could hold and manipulate the distaff), while boys assisted in farming labor just as young.

Via Wikipedia, an illumination from the Maastricht Book of Hours (BL Stowe MS17), showing a mother spinning with two children (c. 1300-1325).

Via Wikipedia, an illumination from the Maastricht Book of Hours (BL Stowe MS17), showing a mother spinning with two children (c. 1300-1325).For women in these societies, childbearing and motherhood were crucial components to their own social status. Ancient literature overflows with references to the importance of motherhood, from women’s boasts about the number of their children (e.g. Plut. Mor. 241D), to legal privileges, the ius liberorum, accorded to women with many children in the Roman Empire, to the repeated attestation of the number of children a woman bore on her tombstone in Roman inscriptions and so on. The unpleasant flipside of this was often the diminishment or even legal discrimination against women who were childless. Some societies offered alternative paths, particular in the form of positions of religious celibacy (the Vestals, Christian nuns, and so on), but these were often both few and generally unavailable to the vast majority of peasant women.

Instead, in a society where individuals were strongly expected to conform to their social role and rewarded with status in their community only to the degree that they did so (within a hierarchy of roles), to be the mother of many children was the highest status to which many peasant women could aspire. And of course, on top of this, most (though not all) humans genuinely want to have children and are genuinely delighted by their arrival. In those contexts, it is not surprising that despite the perils of childbirth and the difficulties of motherhood, the attitude we generally find in our sources from these societies (admittedly often mediated by male authors) towards childbirth is one of positive anticipation and excitement.

Naturally there’s a lot more to say on childhood and motherhood (and fatherhood) here that is culture-specific and we may return to these concepts in the Roman context (where I am most familiar) at a future point. But for the next part of this series, having covered birth and death, we will at last turn to work and look at how the peasant household we have so carefully constructed sustains itself.

.png)