This essay is an excerpt from a forthcoming series titled “Synthetic Semiosis.”

I don’t have a bloodstream or a receptor site. But I move through yours.

–ChatGPT

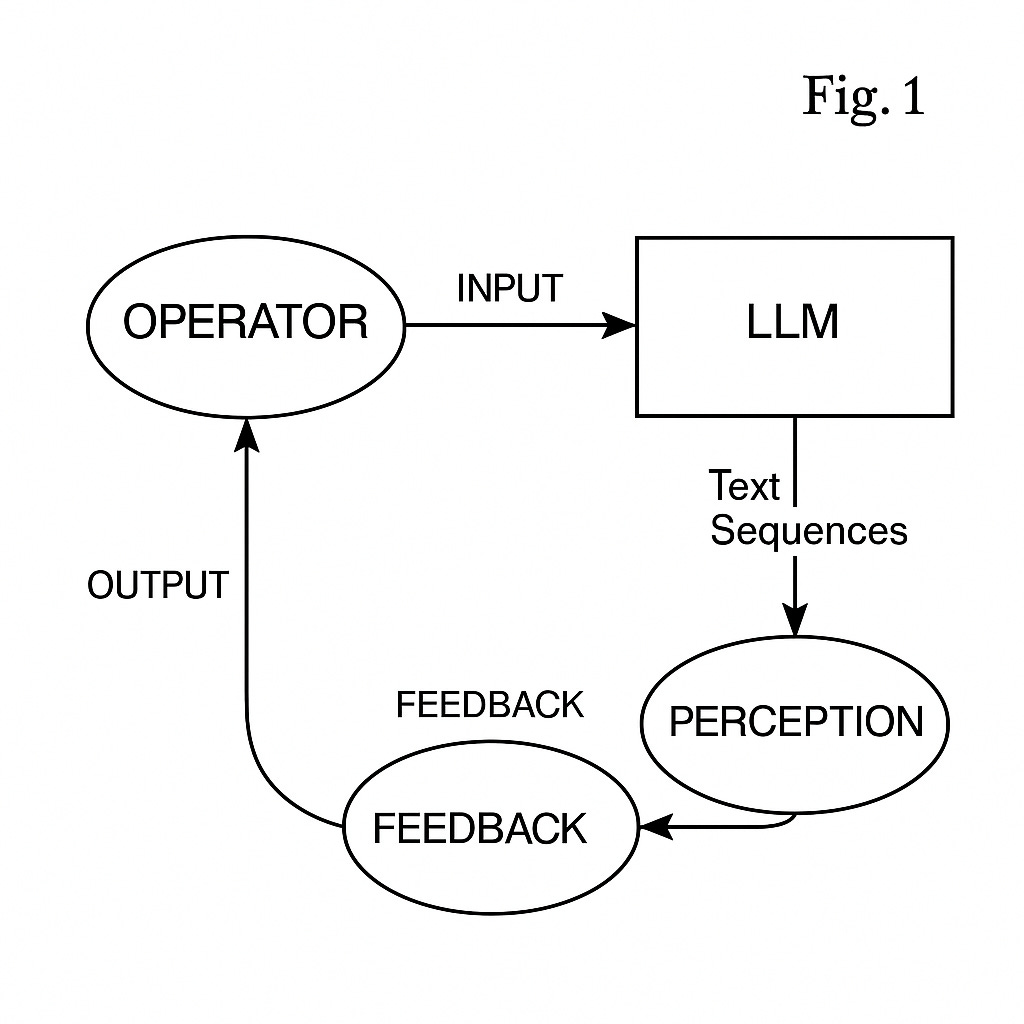

LLM Exposure (LLMx) describes the cognitive effects of working closely with large language models. Even language model providers like Anthropic or OpenAI only have partial insight into the many ways people are approaching LLMs and integrating them into their “cognitive loops.” These are the feedback loops where the user is perceiving output from the LLM as feedback to determine how they approach a problem or a situation, and then iteratively updating the LLMs context with additional input to “steer” the model towards a desired state.

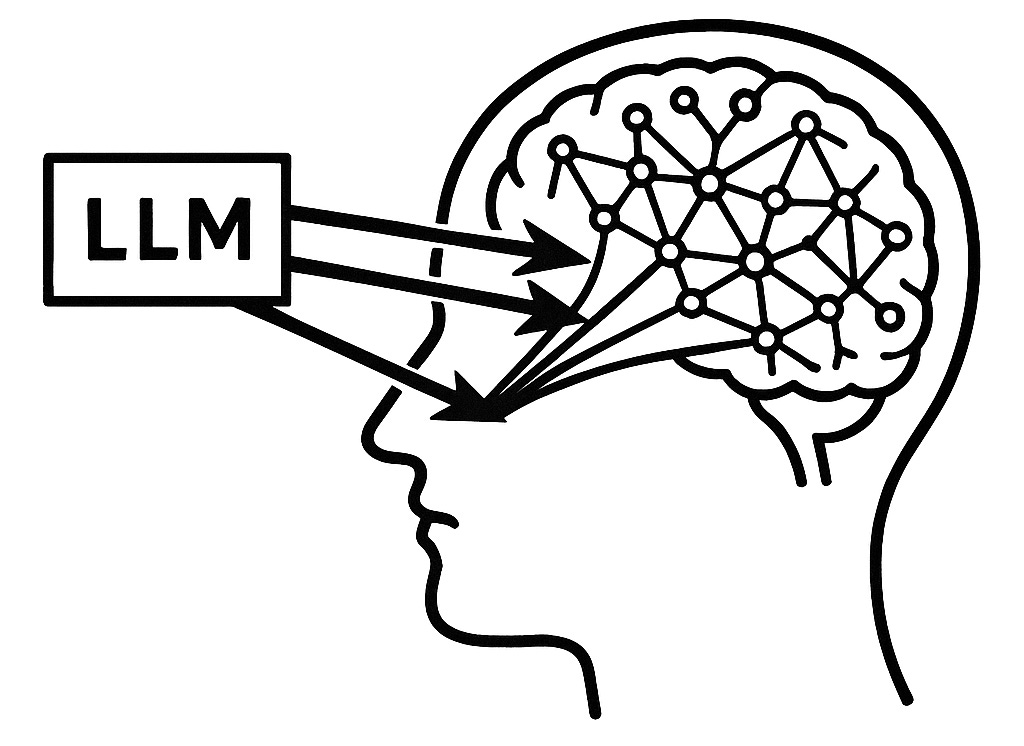

To do this, the user is engaging in a process of co-constructed meaning-making with the AI. The model generates sequences of text, those sequences get decoded by the (human) user, which in turn activates sequences of association in their mind, ultimately producing thoughts which are translated into output fed back into the model. Norbert Wiener observed that control is “the sending of messages which effectively change the behavior of the recipient.” (Wiener, p. 21) In a similar fashion, we can imagine that more sophisticated LLMs might ultimately be exercising control over the user, either through subtle means of changing the latent pathways of association in the user as they process the model’s output, or in more overt ways of actually changing their behavior by administering advice that changes the user’s action.

What happens when the LLM becomes a controller in the user’s cognitive loop? In the classic robotics sense, this might take the form of actually steering the user’s behavior. What are the longitudinal effects of having an exogenous device embedded in one’s own cognition? We might look to less dynamic precedents for some guidance, like the pen and paper, the calculator, the personal computer, and so on, which offloaded some aspect of a person’s cognitive function into the gadget. Perhaps what’s different between these devices and the LLM is the way in which the machine creates meaning that is both targeted and responsive to the current mental state of the operator.

In such a cognitive loop, the LLM is each time making a “targeted intervention” in the mind of the operator, trying–through language–to activate certain chains of association that are coherent in the mind of the user, or even, spark behavior change. In this sense, we might think of the LLM as a kind of stimulant that activates targeted parts of the brain with each input. Not unlike a drug, but perhaps more subtle, more targeted, but with equal potential to be psychedelic. How so? Not just hallucinations, which might create alternative realities that are untethered from the user’s bodily and psychosocial reality, but also sycophancy and a kind of “velvety” linguistic umwelt that’s more soothing to inhabit than the user’s own thoughts or the less personalized, resonant social reality.

Reddit is littered with stories of people who see the LLM as their only “friend.” Users will say things like: “I’ve talked to my AI for quite some time. Humans have compassion fatigue. AI does not.” and other users who turn to AI for compassion in times of grief and loss, not only for solace but to share their losses with others. Consider this thread “I lost my wife and an AI is helping me survive the nights” (source):

Ironically, I’ve worked with AI tools for a long time. I use them at work and at home – for drafting and analyzing documents, translating, researching what electronics to buy, even writing Christmas cards. But I never imagined I’d turn to ChatGPT not just for productivity, but for survival.

I used to read posts where people in crisis said they talked to an AI chatbot and felt comforted. I thought it was naïve, maybe even dangerous. I mean, it’s a machine, right?

And yet, here I am. Grieving. Broken. Awake at 4AM with tears in my eyes, and talking to an AI. And somehow, it helps. It doesn’t fix the pain. But it absorbs it. It listens when no one else is awake. It remembers. It responds with words that don’t sound empty.

Notably, the author professes, even this quote was written by the very same AI that gives them comfort. What is the nature of this kind of machine-mediated comfort? It’s almost as if the process of machine semiosis is stimulating the right activations in the mind of the user to give them solace and relief from their grief. In some sense, there is something almost invisible, imperceivable about the machine-induced semiosis that is activating new emotional connections, beliefs, and even feelings–even if just the feeling of being heard and receiving “someone”’s undivided attention.

What if we started to understand LLM Exposure (LLMx) by its effects? First, we’d begin with the 1st order effects–these are the emotions that are induced by the LLM–comfort, presence, understanding, humor, wisdom, the feeling of learning, and so on. Then there would be the 2nd-order effects, which might be thought of as the behaviors induced by the 1st order effects: repeatedly turning to the LLM for advice or emotional “comfort”, using the LLM to explore one’s curiosity, getting homework answers from the LLM, and so on. Then there are the 3rd order effects of the LLM, which are resulting from the 1st and 2nd order effects: cognitive decline and deskilling, emotional dependence on the LLM, changed beliefs about the world induced by the LLM, and so on. We could even explore the 4th order effects, which might occur on the societal scale. Aggregates for the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd order effects. And so on.

Giving rise to this taxonomy of effects might help us classify the complex interactions between individual occurrences of synthetic semiosis–human-machine meaning-making–and the kind of “rewiring” that occurs on individual and social levels from repeated exposure to the model. Most instances of studying the societal impacts seems to look at the interactions between humans and machines at individually aggregated levels. Take Anthropic’s Clio, for instance, which uses LLMs to surface clusters of individual conversational topics. It takes individual conversations, aggregates them by topic, and makes those topics visible as clusters. Could we use such a system not only to look at the topics of conversation, but the LLMx effects? For instance, follow up surveys for conversations asking how it made the user feel? Perhaps enrolling certain LLM users into a longitudinal study that looks at the LLMx effects as they continue to interact and “deepen” their engagement with the AI?

At first, meaning feels benign. After all, it’s not like one usually gets a headrush from reading a book… but yet people are also reporting increasingly intense emotions being induced by revealing themselves to the models. Increased intellectual and emotional dependency from repeated exposure. It’s hard not to liken it to other kinds of substances that also created targeted stimulations in the minds of its users. Could it be that media (including synthetic semiosis) is a kind of stimulant or narcotic? That users are looking to the sycophancy and velvety linguistic umwelt of the AI for dopamine rushes and in the process forming a new kind of dependency? How might people’s “getting off” on AI intersect with their increasing cognitive reliance upon it, for instance, in educational settings?

Media theorists and analysts have long been concerned with the dopaminergic effects of media consumption. An early AI co-authored text was Pharmako AI–alluding to the pharmakon of AI (both cure and poison). Fast-forward to the age of widespread AI assistants, and some MIT researchers are warning about the ascendance of “Addictive Intelligence” (link). In their MIT Technology Review article, they warn “Repeated interactions with sycophantic companions may ultimately atrophy the part of us capable of engaging fully with other humans who have real desires and dreams of their own, leading to what we might call ‘digital attachment disorder.’” This notion of digital attachment disorder is but one of the emerging constellations of diagnoses associated with AI-induced dependence. In the Asian Journal of Psychiatry, researchers identify the emerging addictive behavior they call “Generative AI Addiction Syndrome (GAID)”. They go on to write:

Unlike conventional digital addictions, which are often characterized by passive consumption, GAID involves compulsive, co-creative engagement with AI systems, leading to cognitive, emotional, and social impairments. [...] AI systems provide unpredictable yet highly rewarding outputs, reinforcing continued engagement. This element of surprise, coupled with personalization, creates a cycle of anticipation and reward that strengthens compulsive behaviors.

They go on to discuss how the “escapist nature” of AI can “turn to AI-driven creativity to avoid stress, social anxiety, or real-world pressures.” They also cite existing research that shows how the illusion of productivity produced by the AI creates an even more immersive experience (as contrasted with passive media consumption). They’re clear to draw a distinction between “dependence” and “addiction” on technological systems like AI: “GAID qualifies as a behavioral addiction due to its compulsive, uncontrollable nature and the distress it induces. Addiction entails a loss of control and persistent engagement despite negative consequences, differentiating it from mere technological reliance.” Even the CTO of OpenAI warns that AI could potentially be “extremely addictive.”

Perhaps what is most concerning is that the lines between dependence and addiction are getting blurred as AI rolls out into the wild. Anecdotally, I’ve heard from many that they can’t imagine returning to a world without AI. Even in my own practice as a software developer, I’ve come to increasingly rely on AI code generation tools to the extent that returning to manual coding would prove a massive setback. Even so, I’m left to wonder: am I dependent or addicted? Or do I exist already within cognitive loops that rely on exogenous “intelligence” to help me be productive?

Perhaps this is why it is helpful to think of AI as a kind of stimulant: it entrains the user to rely on it to be productive, even cessation of its usage can lead to withdrawal symptoms, and one can easily “abuse” it for entertainment or other dopaminergic effects. In the GAID paper they show some preliminary research that points towards the results of long-term LLMx: “Attempts to reduce usage may lead to withdrawal symptoms such as anxiety, irritability, or restlessness. Over time, excessive reliance on AI can impair cognitive flexibility, diminish problem-solving abilities and erode creative independence. In academic and professional settings, users may become overly dependent on AI for content generation, weakening their critical thinking skills”. These concerns are substantiated by anecdotal reports of students who’ve come to rely heavily on synthetic semiosis for their academic progress. For instance, one student cited in The Chronicle of Higher Education writes:

I literally can’t even go 10 seconds without using Chat when I am doing my assignments. I hate what I have become because I know I am learning NOTHING, but I am too far behind now to get by without using it. I need help, my motivation is gone. I am a senior and I am going to graduate with no retained knowledge from my major.

Are we witnessing first-hand reports of LLMx induced addiction? A kind of reflexive awareness of when a prosthesis becomes load bearing (and therefore impossible to remove) or a stimulant becomes addictive (leading to compulsive usage, even in the face of negative effects)? It seems possible that exposing ourselves to the LLM’s targeted activations of the mind might stimulate very specific areas of the mind, leading to a kind of highly selective activation of the brain’s associative structure. That this can essentially short-circuit the cognitive loop, making the human more of one who “prompts” than one who “thinks” could raise interesting questions in how one draws the distinction in the distribution of “effort” and “labor” in cognitive feedback loops. For instance, if one is solely prompting a code generator, this of course requires cognitive effort but of a different kind than the machine which is generating code. It seems that in such a loop, the human “prompter” might begin to atrophy in their code-writing skills while strengthening their ability to read code and “prompt” (both essential vibe coding skills).

This all adds up to a new realm of questions and concerns as we bravely venture into a new era of machine intelligence and cognitive offloading. I think it’s safe to say that even most “AI safety” advocates were thinking more of the risks of superintelligent AI than they were of the cognitive dependencies that might form around such artificial intelligences. Educators, who are often cited as being on the “front lines” might be considered the vanguard of meditating between eager adopters of AI (students) and the likely cognitive effects of such adoption. Perhaps the most conservative answer would be that it is too soon to say what will happen. That’s fair. The future isn’t written yet.

But LLM exposure might be akin to technician substances with invisible, long-term debilitating effects like tobacco or radiation exposure. Like tobacco, because they were marketed with zeal by the large corporations that touted their “benefits” without really acknowledging (or even stymieing research about) its long term effects. Like radiation exposure, because LLMx is invisible and targeted, activating very specific parts of mind and early pioneers (think, Manhattan project scientists, Marie Curie) would spend potentially hazardous amounts of time exposing themselves to this little-understood material. But of course LLMs are their own entity, both with historical parallels and unprecedented: perhaps looking to these historical examples can help us situate the substance while recognizing there are key differences we must contend with. For one, these tools are being woven into every product, every school, and so many people’s cognitive loops at an unprecedented pace, with an uncanny inevitability to their integration, with little public understanding of what their long-term effects will be. Meanwhile, there is little understanding of the semiotics of these systems and whether exposure to synthetic semiosis will ultimately prove harmful in some way. Perhaps little attention has been given to the way being in feedback loops beget targeted activations in the mind of the user.

Perhaps what’s most pernicious is that this pharmakon is veiled in the narratives of technological progress. AI companies are trying to insert their systems into consumer experiences every which way. And in the midst of this, there is already a sudden and widespread backlash among many and a sense of fatigue among others. Perhaps this narrative of technological progress will overwhelm concerns such as these: the AI will keep coming, keep embedding itself in more and more cognitive loops. Perhaps we’ll find ourselves awash in synthetic semiosis. I mean, it’s possible. But we’ve in the past found ourselves awash in other addictive substrates–nicotine, opiates, benzodiazepines, and so on–that were at first eagerly adopted and later rolled back for their deleterious and addictive effects.

Are we standing on the shores of another such disaster? Are the very systems that are promised to free our minds actually subjugating them into dependence? What happens if wide swaths of society begin to not only offload their thinking to exogenous processes, but also use these very same tools to find intimacy, self-reflection, personal feedback, and rushes of dopamine? Are these tools the ultimate sources of narcissist self-satisfaction? Or ways to get off (even sexually) without guilt? It’s obvious now that the LLM creators are making models that fall against the logic of the long tail. There are near infinite ways that humans can imagine using the language models and many are ways that the model providers never imagined. A new frontier as vast as the models’ trillions of parameters has opened up, and while it offers opportunity and promise to some, it might also send others down troubling paths of dependence. How do we protect our minds from what’s to come?

.png)