The US, known for its extensive defense-industrial complex, has some of the world’s largest defense contractors. The world’s top five defense contractors are all American firms. Ironically, this might be the reason the US can lose the next major war, despite being the largest economy on earth.

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), in 2023, Lockheed Martin, RTX Corporation, Northrop Grumman Corp., Boeing, and General Dynamics were the world’s biggest arms-producing and military services companies, respectively. Nine of the world’s top 20 defense firms by revenue were American, and 41 US firms featured in the SIPRI list of the world’s 100 biggest defense companies by revenue.

However, what was once considered America’s strength is quickly becoming its Achilles’ heel. Multiple government reports, research papers, and defense experts are warning that the U.S. defense industry, dominated by a handful of massive contractors, has become too bloated. This is stifling innovation and driving up costs for military platforms.

The inefficiency, critics argue, is now built into the system, which burdens taxpayers and undermines the U.S. military’s competitiveness compared to leaner, more innovative systems developed by nations such as Russia, Iran, China, and India.

“The United States is in urgent need of fundamental defense reform. Not just adjustments. Not just marginal gains. A full-scale overhaul. The wars of today…will not be won by the slow, the bloated, or the bureaucratically constrained. They will be won by those who can think faster, build faster, and fight smarter,” warn John Spencer and Vincent Viola, in their latest essay in the Small Wars Journal.

US Army. Edited Image.

US Army. Edited Image.However, this apocalyptic situation did not emerge overnight. It was years, if not decades, in the making. The warning signs were there. Red flags were raised. But, it seems that once again, the wicked logic of ‘Too Big To Fail’ is at work here.

Rising Defense Budgets, Shrinking Prime Contractors

In 2020, the U.S. defense budget was approximately $721.5 billion. For the financial year 2025, it was capped at $895 billion. However, last week, the House passed a massive GOP-backed funding package, paving the way for Congress to add $150 billion in defense spending, bringing the total defense budget for the current fiscal year to a historic one-trillion-dollar mark.

This represents an over 40 percent increase in defense spending over a five-year period. However, while defense spending is increasing at an unprecedented pace, the number of prime US defense contractors is shrinking at a troubling rate.

A February 2022 study by the Department of Defense (DOD) found that after decades of consolidation, the number of defense prime contractors had shrunk from 51 to fewer than 10. Further, many segments of the defense market have become controlled by companies with monopoly or near-monopoly positions.

During his first term, US President Donald Trump has also warned that the US defense companies have “all merged in, so it’s hard to negotiate… It’s already not competitive.”

Furthermore, a June 2024 Congressional study, “Defense Primer: Department of Defense Contractors,” found that five Companies (Boeing, General Dynamics, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Raytheon) typically received the majority of departmental contract obligations each fiscal year.

This concentration has created a cartel-like situation where a few giants dominate the market. Furthermore, the cost-plus contracts, which shield companies from overruns, and the Pentagon’s detailed midterm modernization plans provide stability but discourage risk-taking.

As a result, the Department of Defense (DoD) struggles to integrate cutting-edge commercial technologies, leaving the U.S. military reliant on outdated or overpriced systems.

“America’s defense manufacturing process is dominated by a small cartel of primes that, while capable, have little incentive to drive innovation, reduce cost, or adapt quickly. There is no real market competition. This is not competition—it’s cartelized domination,” John Spencer and Vincent Viola warn in their essay.

Insulating Defense Firms From Wider Market Forces

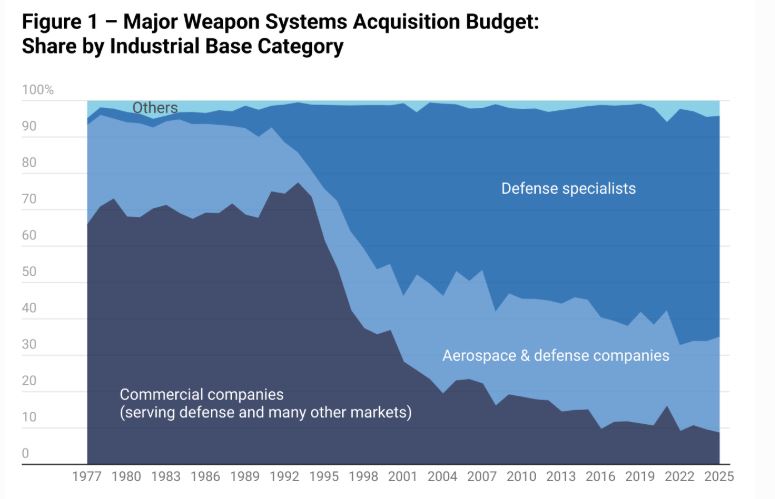

A 2024 CSIS study refers to a dataset that tracks DOD expenditure on so-called Major Defense Acquisition Programs (MDAPs) dating back to 1977. The dataset identifies program prime contractors by their industrial base sector.

Defense specialist firms with little or no commercial business account for 61 percent of the DOD’s major programs by value in 2024, up from just 6 percent when the Berlin Wall fell in 1989. When including firms whose only commercial exposure is in aerospace (such as Boeing), traditional DOD suppliers account for 86 percent of major program spending in 2024.

Credits CSIS.

Credits CSIS.In contrast, companies with exposure to other sectors of the economy accounted for over 60 percent of the DOD’s major programs by value until around 1995, when their share witnessed a steep decline. By 2024, their share had fallen to a paltry below 10 percent.

How did this massive reversal happen? The CSIS study states that following the breakup of the Soviet Union in the 1990s and the end of the Cold War, the US defense budget underwent significant cuts.

This led many companies to exit the defense market. These defense subsidiaries of commercial companies were often bought by companies exclusively in the defense sector.

For instance, the Ford Motor Company had a subsidiary, Ford Aerospace, which manufactured missiles and satellites. Ford sold off the subsidiary in 1990 and exited the defense market. The Ford subsidiary was acquired by the Loral Corporation, which was subsequently acquired by Lockheed Martin in 1996.

At that time, when defense budgets were shrinking, the consolidation of companies in the defense sector was considered essential. However, after the 9/11 attacks, when defense budgets started rising once again, the trend continued, leading to the current scenario.

Today, most large US companies in the defense sector have minimal exposure to other market sectors and are thus largely insulated from broader market forces. This also discourages innovation.

File Image

File ImageUnsustainable Cost Structures

These defense firms, which have monopolized a massive share of DOD contracts and are often insulated from wider market forces and risks, often prefer incremental improvements over disruptive innovation.

The cost-plus contracts, which shield companies from overruns, discourage risk-taking and often produce complex, over-engineered, and overpriced military platforms. In contrast, countries like Russia, India, China, and even Iran are producing systems faster and often at a fraction of the cost.

Take, for instance, the case of the F-35. No doubt, it is one of the most advanced fighter jets. However, with a lifetime cost exceeding US$1.7 trillion, the F-35 has faced criticism for delays, cost overruns, and technical issues. In contrast, Russia’s Su-57 stealth fighter and China’s J-20, while less advanced in some areas, offer a cost-effective alternative for their needs.

The US has also learned from the expensive F-35 mistakes and is determined not to repeat them in the F-47.

File Image: F-47: Artist’s Rendering.

File Image: F-47: Artist’s Rendering.The US Air Force now wants access to all the sustainment data it will need from Boeing, the contractor building the F-47.

In May 2023, Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall stated, “We’re not going to repeat what I think frankly was a serious mistake that was made in the F-35 program” of not obtaining rights to all the fighter’s sustainment data from contractor Lockheed Martin.

Kendall explained that when the F-35 program was launched, an acquisition philosophy known as Total System Performance was in favor. Under this approach, a contractor that won a program would own it for its entire lifecycle.

“What that basically does is create a perpetual monopoly,” Kendall said.

Similarly, take the example of the U.S. Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System (GMLRS), produced by Lockheed Martin. It costs approximately US$148,000 per missile. In contrast, India’s Pinaka rocket system, which offers similar precision, is produced at a significantly lower cost, with estimates suggesting each rocket costs under US$56,000.

Enhanced PINAKA rocket, developed by the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) successfully flight-tested from Integrated Test Range, Chandipur, in Odisha on November 04, 2020.

Enhanced PINAKA rocket, developed by the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) successfully flight-tested from Integrated Test Range, Chandipur, in Odisha on November 04, 2020.India’s ability to integrate commercial technologies and leverage domestic manufacturing has enabled it to scale production efficiently, a flexibility that U.S. contractors struggle to match due to their insular supply chains.

The same is true of drones, which are widely regarded as the artillery of future wars. Iran has developed low-cost drones like the Shahed-136, used effectively in Ukraine, for as little as US$20,000 each. In contrast, the US MQ-9 Reaper drones cost a fortune. A single unit can cost over US$30 million.

Similarly, India’s indigenously developed Akashteer missile-defense system, which showcased its potential in a real combat situation during the recent India-Pakistan clash, was developed at a fraction of the cost compared to expensive US missile defense systems like NASAMS or Patriot.

With a contract value of just $270 million for a full suite of integrated capabilities, Akashteer showcases India’s ability to deploy high-performance, scalable systems without the financial burdens typical of the US platforms.

“US defense giants produce exquisite systems, but often at boutique pace and boutique prices. There is no agile, scalable, layered, fast-response production network. No real surge capacity. The primes effectively control the process from design to deployment, and they are not optimized for the speed or scale of modern war,” John Spencer and Vincent Viola write in their essay.

HISTORIC! First Freight Train From China Wheels Into Iran, Flying In The Face Of American Sanctions

The Way Forward

According to the essay by John Spencer and Vincent Viola, the US cannot win a war it can’t afford, scale, or keep up with.

“The time for US defense reform is not coming. It’s already late.”

The essay suggests that if the United States wants to remain a global military power, then it must:

- Rebuild the acquisition process around speed, iteration, and field feedback, not static 10-year programs.

- Break up defense industrial monopolies or at least introduce real competition and alternative suppliers.

- Shift focus from perfection to effectiveness, from gold-plated systems to scalable, rugged, modular platforms.

- Treat allies like India and Israel as co-equal production partners, not just buyers or tech recipients.

The White House also recognizes that the US defense acquisition policy is slow and outdated, and it desperately needs an overhaul.

“Unfortunately, after years of misplaced priorities and poor management, our defense acquisition system does not provide the speed and flexibility our Armed Forces need to have decisive advantages in the future. In order to strengthen our military edge, America must deliver state‐of‐the‐art capabilities at speed and scale through a comprehensive overhaul of this system,” said a White House executive order released last month.

It also directed the Secretary of Defense to submit a plan to the President within 60 days to reform the Department of Defense’s acquisition processes.

However, despite these realizations and repeated warnings, it remains to be seen whether the US has the wherewithal to ignore vested interests and overhaul its defense industry.

To win future wars, the US needs a system that can innovate, produce economically, and scale quickly.

- Sumit Ahlawat has over a decade of experience in news media. He has worked with Press Trust of India, Times Now, Zee News, Economic Times, and Microsoft News. He holds a Master’s Degree in International Media and Modern History from the University of Sheffield, UK.

- THIS IS AN OPINION ARTICLE. VIEWS PERSONAL OF THE AUTHOR.

- He can be reached at ahlawat.sumit85 (at) gmail.com

.png)