Nov 5, 20254 minutesDotfiles, GNU

Nov 5, 20254 minutesDotfiles, GNUI came across GNU Stow as a way of organising dotfiles in an interview between Matt from The Linux Cast and Linkarzu on YouTube: Matt from The Linux Cast on macOS, NixOS, Emacs & More. I migrated my own dotfiles to the GNU Stow structure and was amazed at how efficient and elegant this solution is.

What are dotfiles?

In case you’ve never heard of them, dotfiles are the configuration files for your installed apps. They are usually hidden and therefore prefixed with a dot (e.g. .vimrc).

All these files live in your home directory and subdirectories such as .config. Every application stores them somewhere in there. However, it’s not standardised, so there is definitely some uncontrolled growth.

Backing up and managing all these files is essential if you want an easy way to reproduce your configurations across multiple devices. A dotfile Git repository is a pretty efficient way to achieve this.

My old dotfiles repository

My old dotfiles structure was simple: it was essentially an exact replica of my home directory containing my chosen configurations. I started by managing my home directory as the repository, using a rather impractical alias for this purpose:

It was a horrible time. Don’t follow my example.

So, I switched to a decoupled repository and symlinked all the files to my home directory using the command ln -s repos/dotfiles/.vimrc /home/lukas/.vimrc. That was an improvement, but still inconvenient.

What is a symlink?

In GNU/Linux, a symlink is simply a file containing a path to another file. Nothing more, nothing less. In fact, the path doesn’t even have to exist. This is the opposite of a hardlink. A hardlink is a directory entry that points to the same data (inode) as the original file.

Here is a ‘visual’ example:

- symlink = path to the door to the data

- hardlink = another door to the same data

The only difference when creating a link is the -s option of the ln application. Without it, it’s a hardlink. Adding it results in a symlink.

How GNU Stow improved my dotfiles

GNU Stow is a smart way of implementing symlinks that I created manually. It’s that simple.

To install it, just look up stow in your distribution’s repository.

stow takes multiple packages as arguments; for example, stow package_a package_b. A package is the first subdirectory level of the directory in which stow is executed. For example, in the following tree-view, vim and zsh are packages:

GNU Stow also comes with a default ignore list, meaning that your .git directory, for example, is not considered a package. See the GNU Stow’s default-ignore-list for details.

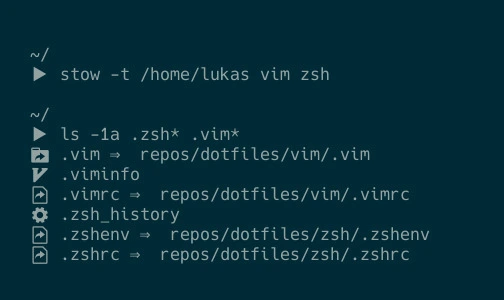

When running GNU Stow, you can specify a target and an optional source directory. It then creates symlinks for all the files contained within the package. Let’s use the vim and i3 packages as an example:

%l produces the same result as running readlink /home/lukas/.vimrc, for example. It simply reads the plain path content of the symlink.

As you can see, this is a useful way to selectively create all the symlinks of a package. One major benefit for me is the clear separation of packages and their dotfiles. Of course, if you have multiple packages with dotfiles in the .config directory, you will also have multiple .config subdirectories in your different packages. But for me, that’s a plus.

What is your opinion? Do you like the concept? Let me know on Mastodon! @[email protected]

.png)