There are lots of management books for technical workers or for project management. Books like The Mythical Man Month or Peopleware: Productive Projects and Teams. These books offer deep insights into how to structure and organize engineering teams and also how to skip making common mistakes (e.g., treating technical workers as cogs in a machine instead of highly skilled individuals). However there aren’t any books, that I know of, that are strictly about managing science. And that I find to be particularly odd because I would think scientists would have a lot to write on the topic as they have a lot to write about in general. As a scientist I would guess maybe half my job is writing either papers or through correspondence. So, given the lack of any literature, at least to my knowledge, on scientific management I decided to write between one and many substack posts on the topic to get the conversation started. This post will be about knowledge management, but others might include topics like project design and management, and people management.

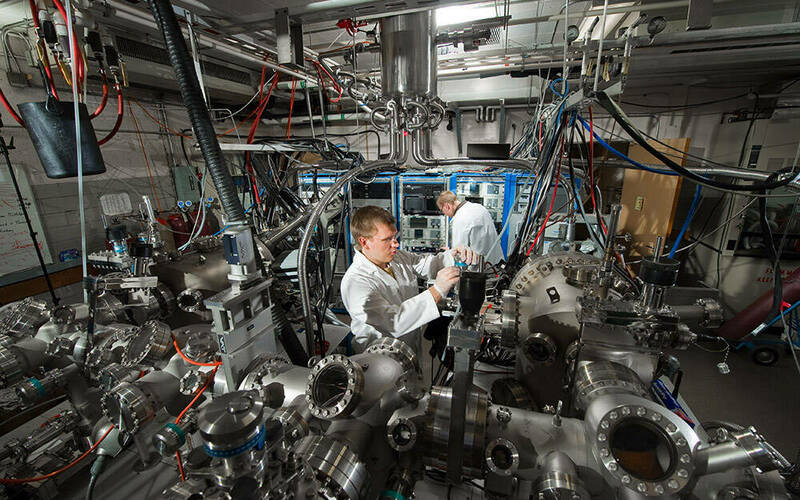

There are already plenty of books out there on technical management so why write any on science management. This is kind of true, but science often has a hierarchy and a nebulous goal structure that doesn’t align with the goals of engineering teams. For example, PhD students are an integral part to most academic science teams, they are also junior members, with an end date to their work (this is also true for postdocs). Unlike junior software developers or engineers which you might imagine you are training to become seniors in your company with a deep technical insight across the technology stack that comes from experience with that stack, PhD students and postdocs ALWAYS go away. Thus, scientific managers (i.e., professors and senior research scientists) are constantly juggling project knowledge needs. There are a few ways of doing this but one is to simply move on to a new topic when the group of PhD students who knows about it leaves. This can lead to a lab (see the physics lab below) which may be full of useful equipment or it may be full of equipment nobody knows how it works.

Another option for knowledge management is to try and hold on to PhD students for as long as possible. A typical example looks like this. A PhD student who clearly understands how a piece of research technology work graduates. They are offered a postdoc within the lab and are encouraged to stay. The postdoc funding runs out. The PI manages to get a teaching position created within the department or perhaps they are super lucky an internally funded research position that may allow for some permanency. The former PhD student teaches and advises on the research. This continues until the former PhD student leaves and goes some place else. Neither solution is wrong per se, but neither seems like a thoughtful research management choice or strategy. Instead it is a reaction to the creation of a knowledge gap because the knowledgeable researcher in your lab leaves.

There are predictable points when PhDs and postdocs transition out of the lab. Depending on the country you are in, PhDs have a finite contract (in the USA this is not true) and are essentially working for free if their PhD dissertation is not submitted at the end of the contract. Thus you can expect the PhD student will work with you for approximately the length of the PhD contract. In the USA, students are offered teaching stipends and can, within reason, work indefinitely on their PhDs. Postdocs have a finite contract as well. It doesn’t matter their performance, if they publish 100 papers during their postdoc or 0 papers, at the end of the contract, the money runs out and they must either find new funding or a new job.

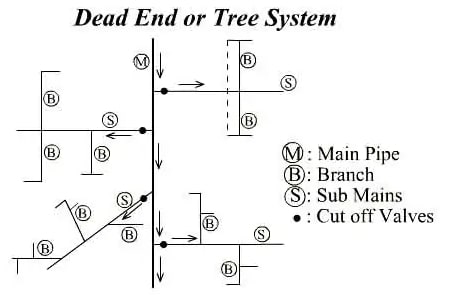

Because there are predictable points when knowledge will transfer out of your research group, we could imagine a strategy to keep knowledge within the group. One strategy, which is also reactionary in my opinion, is the expectation that when PhD/postdoc leaves, collaboration continues. This is a reasonable expectation if they leave for another academic position, academic positions typically come with a lot of freedom and thus they will likely have some time in their new job to assist the transition in their old job. Another would be a technological solution, if PhDs and postdocs document everything they do, e.g., by using a wiki, then knowledge is in some ways passed forward. In my experience this doesn’t work. Across all of the research groups that I have worked in across different cultures, wikis have never been kept up to date, and they don’t really capture the scientific process anyways. That is perhaps because science isn’t building solutions to problems, it’s exploring problem spaces looking for new ones. There is a lot of dead ends there.

Another strategy, that I would like to attempt but have not yet, is that everyone in the group is expected to contribute to a core software library. This will create a sort of monolithic project that group members add to as they come and go. This is how a lot of statistical packages have been born, perhaps not explicitly as knowledge management tools, but as research outputs. The risk here is that your package becomes all encompassing as you add more and more features to it and many years from now you realize your entire work life has been consumed by managing this software package. There isn’t anything wrong with that, but it should be part of an overall research strategy and not something you fall into and then hate.

Of course I am also leaving out one critical piece of scientific knowledge storage, the scientific paper. There is a, now retired, scientist at UT-Austin Institute for Geophysics, who when asked periodically about details of papers he would reference during colloquium Q&A sessions, would say, “You should read my paper because I wrote this down so I wouldn’t have to remember.” And that is a critical component of how knowledge transfer and storage happens in science. It is written down and stored in journal articles. The modern research paper serves lots of functions, but I think a critical one can be storing how things work inside of a research lab. To that end we should try and best capture our computational work so that it can be repeated. I have written about this before on how to avoid common errors in adding codes to scientific publications.

I think this sits between some sort of monolithic software library and doing nothing. But I also think the scientific paper isn’t a management strategy for knowledge transfer, it is simply a deliverable of scientific endeavors. You can expect new members of your lab to read old papers, but how that knowledge is carried forward and leveraged is still an open question for me.

I think every scientist as they mature develops their own personal views on how science should be managed. It is probably quite useful to organize those views from lots of scientists and put them into a publication somewhere. Perhaps there already is a field that studies this. If not, maybe one should start.

I want to say thanks to the group at Asterisk Labs for pushing me to write this. I was initially skeptical since I don’t have decades of experience of scientific management. They said, yeah but you have thoughts and maybe those thoughts can shape the future even if they are only now theoretical.

.png)