(The title and bits of the text of this newsletter come from a notebook post I wrote a while back, but I’ve expanded it a lot.)

About a year ago I started learning classical piano with the partimento method, a bizarrely effective teaching style from 18th century Naples, and wrote up some background in Improvise like it’s 1799.

I’m still going and if anything I’m even more enthusiastic now. It’s possibly the most satisfying experience I’ve ever had learning anything. This is particularly weird because I’ve been learning on my own from YouTube videos and an unpromising looking rulebook from 1801, Furno’s thrillingly titled An Easy, Brief, and Clear Method Concerning the Primary and Essential Rules for Accompanying Unfigured Partimenti.

It’s also been an oddly moving experience. At the end I’ll cough up some words about that, which will probably not be very successful because I don’t understand it very clearly myself. But I’ll start with trying to explain what the method is and why it works so well.

I’ll focus on Furno, because that’s what I know at the moment. His rulebook is the most beginner-friendly of the surviving ones and gets you to the point where you can play the simplest partimenti (this is where I am now). I’ll say more later about exactly what partimenti are, but roughly speaking they’re short pieces where you’re given the bass line only and have to work out how to “realise” them as full pieces by improvising top parts that make sense.

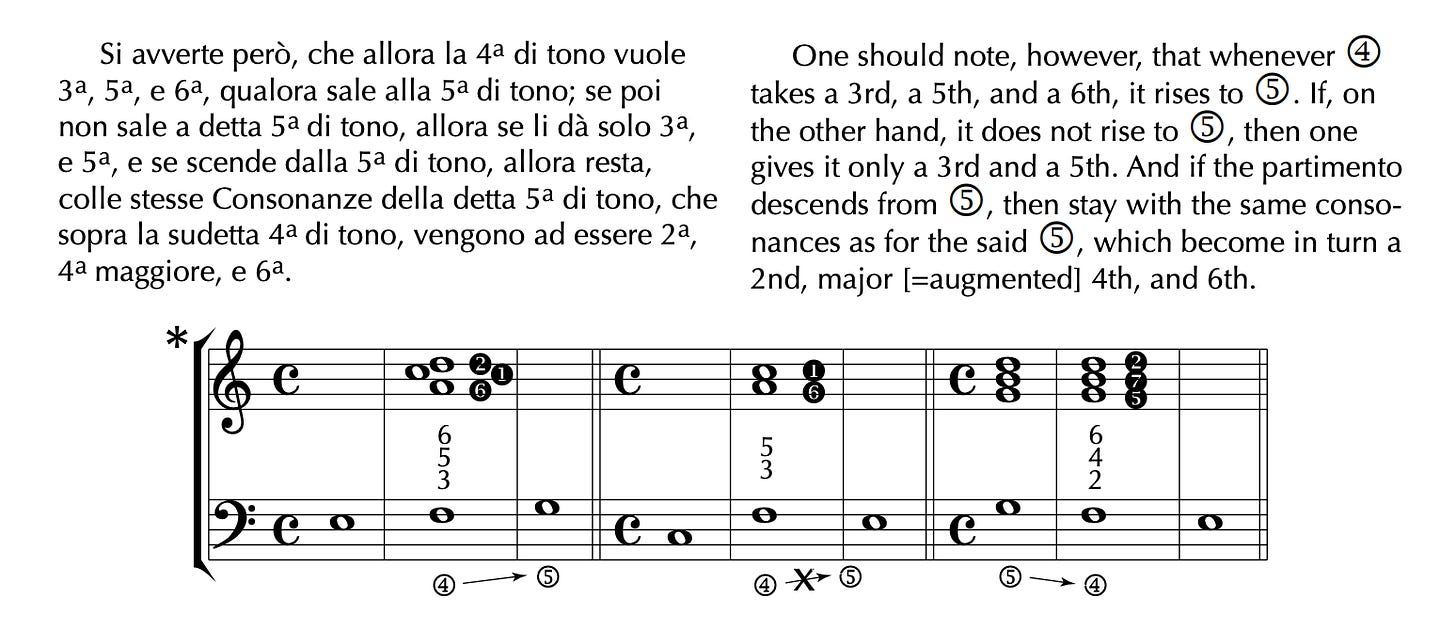

I’m definitely not reading Furno for the exciting prose style. The instructions are terse, dry, almost legalistic. I’ve read API reference docs that are more fun than this:

But the way to think of Furno is as something like a game rulebook (it literally is a book of regole, rules). The game rules are dry written out without context, but the game itself is not. The rulebook gives you a clever breakdown of the main techniques you need to improvise in this style, and a method for how to build them up in stages.

To explain this, I need to give some quick historical background. Furno and the other partimento teachers taught in Neapolitan conservatories for orphan boys. The idea was to teach the orphans some kind of trade so that they could support themselves as adults by working as professional musicians. They didn’t need to be Mozart, but they did need to be competently trained all-rounders who could perform, accompany and compose reasonable quality music for courts, churches and opera houses. In the days before recorded music you needed to employ a lot of decently competent trained musicians who weren’t geniuses but who were right there, in your particular town.

As a technical writer, something about this pragmatic orientation resonates with me. I write a lot of tutorials, reference docs, “how to integrate X with Y” guides, that sort of thing. I genuinely really like this work and try to do it as well as I can, but I’m aware that it isn’t immortal work for the ages and it mostly just needs to get a job done. I like thinking of music in the same way that I think of writing, as a vast and mostly unremarkable background that has the raw materials to allow great art to emerge from time to time, but where you don’t need to be particularly precious about the median piece of it. (This is maybe obvious, but can get obscured in classical music where you only hear the stuff that survived for hundreds of years, which tends to be unusually good.)

Partimento teaching centred around learning a simplified, cut down model of classical music (which I’ve been thinking of as “minimum viable music”). You then learned to repeatedly elaborate it until it sounded like real music that you’d actually want to listen to. This was all hands-on, trade-school-style learning at the keyboard, with the minimal amount of theory at each step that would allow you to do the next thing.

First, students would learn something called the Rule of the Octave, a default musical language which gives you a standard chord to play against every note of a ascending and descending scale in the bass.

The beginning of this video by John Mortensen shows you what it sounds like:

I've found that even this is weirdly satisfying to practice! Normal scales are pretty boring, and I only practice them because they're useful, but the Rule of the Octave is actually enjoyable.

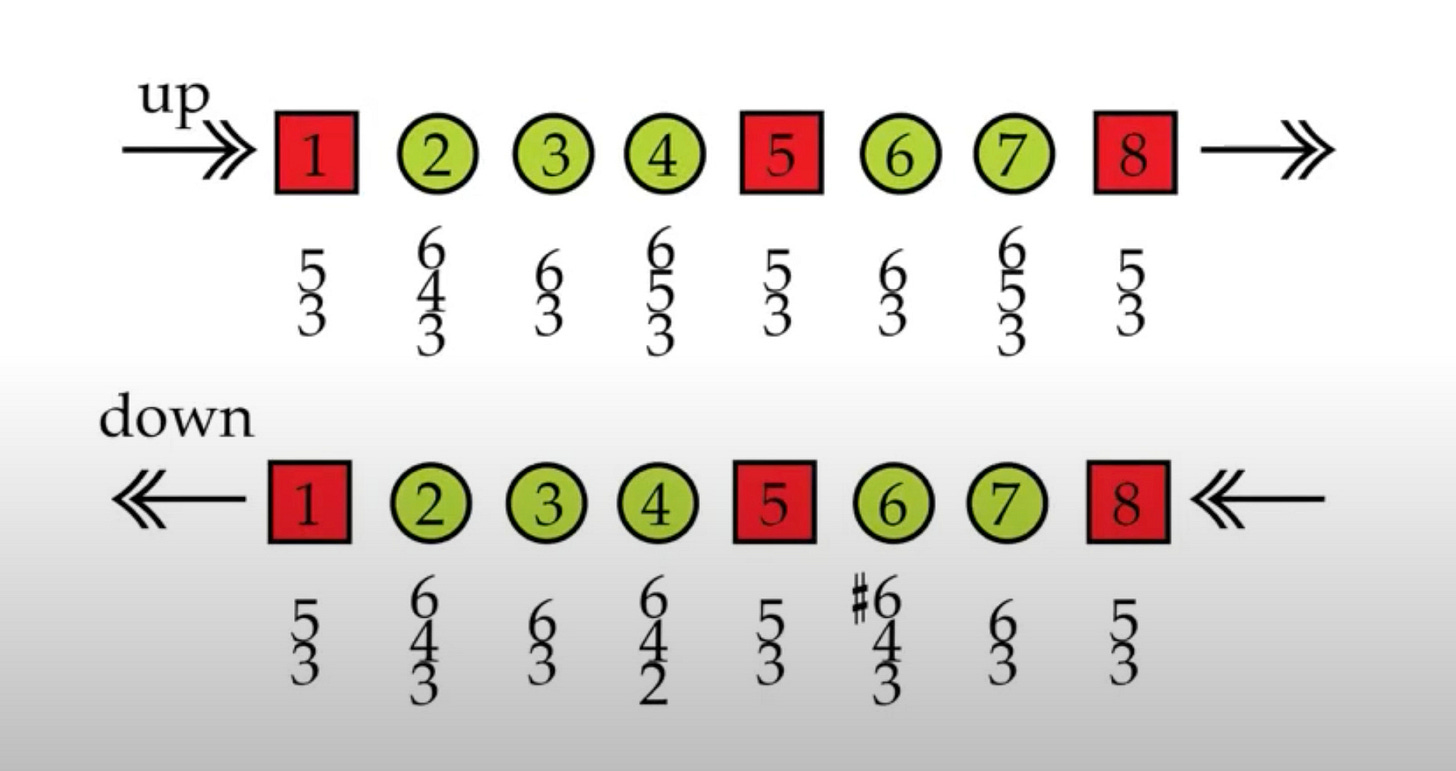

This is because it works as minimum viable music. Like storytelling, music unfolds in time and gets a lot of its interest from the creation and release of tension. The Rule of the Octave has this built in from the start. The details don't matter, but this diagram (screenshotted from a video by Robert Gjerdingen) can give you a rough sense of how it works even if you don’t know any music theory:

The red squares are stable points in the scale, and you put a stable-sounding, solid chord on them, the sort you’d normally plonk down at the end of a phrase. (The numbers underneath are notation for these chords. The 5 and 3 under the red squares represents the 3rd and 5th notes in the scale above the given bass note, which give a particularly solid chord when played with the bass.)

The green circles are unstable points, and you give them a less solid-sounding chord with a 6 in it. As you approach a stable point, you add more dissonance to the chord to add tension. You then release the tension at the stable point with the nice solid 5/3 chord. You need a different ascending and descending scale because you approach the stable points from different sides, so the patterns of setting up and releasing dissonances are different.

There's one extra complication, where position 3 in the scale is treated as sort of half-stable, half-unstable – it gets a 6 chord like the other unstable points, but you also increase the dissonance as you approach it, like you would for a stable point. But this is already going into the weeds too far – the important part is just the idea of unstable-to-stable transitions.

These are the basic building blocks that more complicated classical music is made out of, so the Rule of the Octave automatically sounds like slightly bland background music. As Mortensen puts it:

It sounds absolutely normal and correct and kind of boring. Because so much of the music we know was made of this. This was the formula they were using. And that’s why it just sounds like a hymn, and it sounds like a string quartet, and it sounds like the slow movement of a something, and it sounds like the prelude of something else.

After learning the Rule of the Octave, students would apply it to bass lines that were more complicated and interesting than a scale. This is where partimenti came in. The very earliest partimenti in Furno can be realised by just putting Rule of the Octave chords above the bass line.

If you move a bit later in the Mortensen video you can see him realise Furno 1, first the way that a beginner like me would play it, with simple block chords, and then as a full improvised piece.

Importantly, you don’t just realise a partimento once and move on to the next one. Even as a beginner, there’s a lot of variations you can try - you can play it in different keys, or stack the chords in a different order, or switch out the block chords with broken chords in different rhythms, or see if it works if you swap it from major to minor. You absolutely have to do this (particularly the different keys and orders) because you’re training fluency. You need the patterns in muscle memory so that you can improvise in real time, and learning a single version is too brittle to be any good for that.

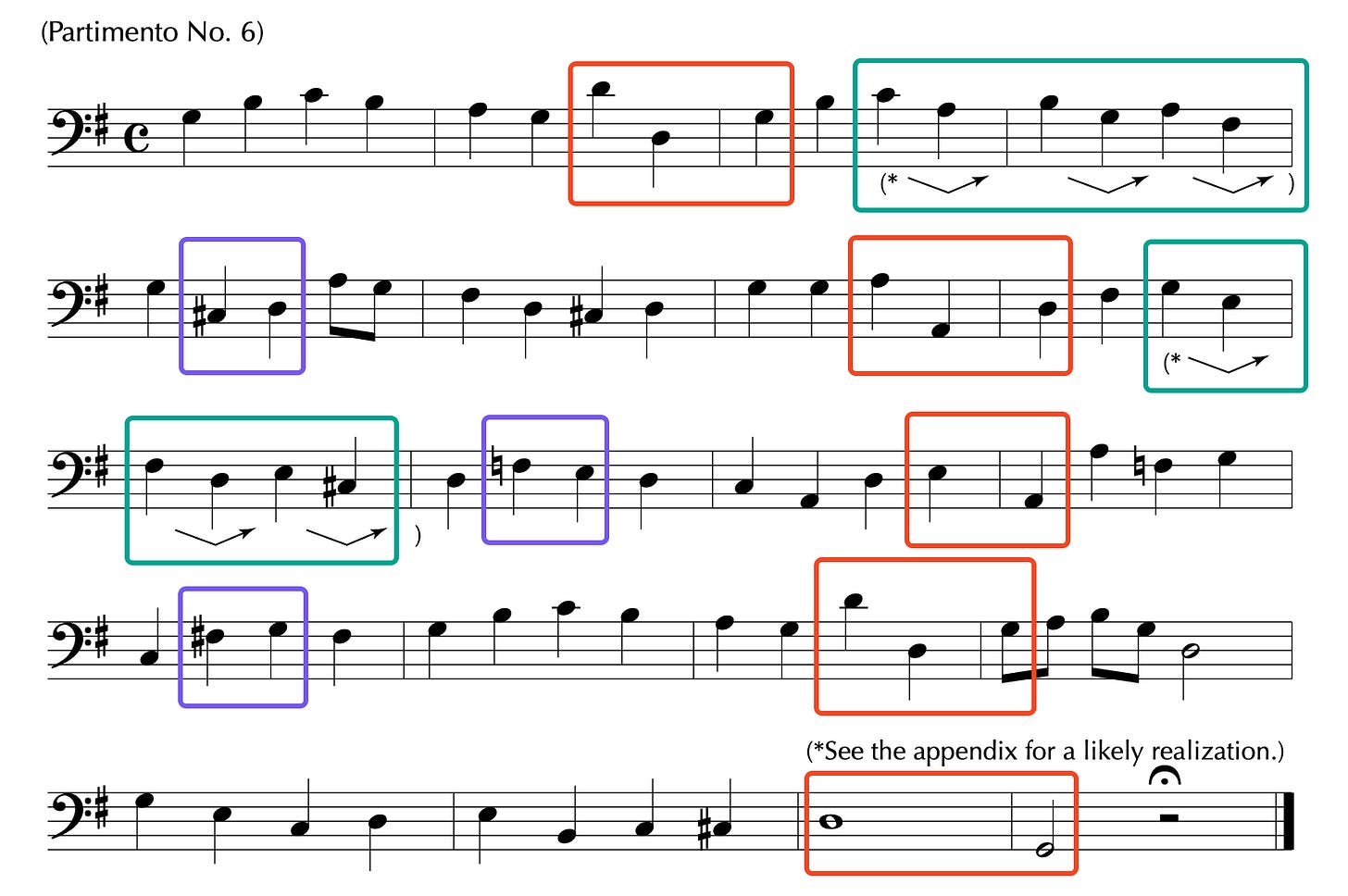

Later partimenti introduce new rules for specific patterns in the bass. To give a sense of what that’s like, I’ll show you Furno 6, which is where I’m at right now:

The colours I’ve added represent different patterns:

Ends of phrases (“cadences”) are in red

Key changes are in purple

Repeating sequences (“moti del basso”) are in green. At this point Furno has introduced a single type of repeating sequence, where the bass jumps down by a third and then steps up again by a second.

Patterns in the bass are a clue that you’re in a situation that needs different rules to the default Rule of the Octave. The clever thing is that these new rules are still cut down “minimal viable” versions of the thing they’re teaching, in the same way that the Rule of the Octave is a minimum viable default musical language. For example, in real music of the time cadences can be pretty complicated and nuanced. Furno boils it down to the following rule: there are three types of cadences. There's a short one that you play if the fifth in the bass lasts for one beat, a longer one for if it lasts two beats, and a fancy long one for if it lasts four beats. Stick the appropriate one into your partimento and you're done.

This is not sophisticated, but it's still somehow just enough. Furno 6 is beginning to sound pretty convincing. There’s a few bars of opener, then it launches into a pattern, then changes key, repeats the pattern in the new key, makes a short excursion into a minor key, finds its way back to the original key and does a big cadence to finish. This is the kind of structure you’d find in a short piece of “real” classical music. Here’s a recording by Hiroko Asai that plays through Furno 6 twice, first with a simple version (still a little more complicated than what I would play as a beginner, but similar), and then a more advanced realisation:

The fact that you’re always playing music makes partimenti very satisfying to work through. It’s not like grinding through scales, or through boring studies that just train a particular technique. This is also why they feel game-like. There's always an obvious next thing to work on, and you can progress through the levels and make incrementally more complex music.

As with the previous newsletter, I feel like I’ve done ok at explaining what partimenti are, but I’ve not really got across what I find so moving about the revival of this tradition. So let’s finish with another round of totally failing to dredge up the right words.

I’ll start this video of the the pianist and composer Alma Deutscher learning partimenti and classical improvisation as a child. I’ve skipped the four-year-old-plays-scratchy-violin bit and linked to her earliest piano improvisation video, at the age of five:

It’s astonishing for a five-year-old, but also globally structureless, lots of little bits of recognisable classical idioms chained together into a kind of endlessly morphing DeepDream proto-music. If you keep playing the video, you’ll see that a year later she’s improvising organised pieces with long-range coherence, and then by nine she can play amazing improv duets like this, which I linked in my previous newsletter. But it’s actually that first video of her as a five-year-old that I find really striking – it’s like getting a glimpse of the background that music emerges from.

When I’ve watched videos of child prodigies in classical music before, they are incredibly talented at performing on their instrument, but they normally perform existing repertoire only. They don’t do this fascinating thing of babbling long streams of musical fragments that then start to cohere into recognisable music. They also don’t become composers. When I watch the Deutscher video, it seems obvious that she’s learning a method that taps into the same superabundant stream of musical patterns that the great composers had access to. It never got exhausted by modernism. It’s all still there.

The obvious reason for bringing back the partimento tradition is to understand and revive old music. That’s what I’m mostly in it for; I just want to learn to play music in the galant era style that I love. But it transmits so well that I feel like it can do more than that. It also feels wide open to the future, a living structure that can pull in and transform other musical material to create new styles as well as old.

Well, that will do for a second attempt at explaining why I care about partimenti. I’m not sure what I’m going to do after Furno 6. I could play through the rest of the levels up to Furno 10 and beat the game, or I could follow Robert Gjerdingen’s guide and switch rulebooks. Or both. It’s still amazing to me that this actually works.

.png)