The Bahamas is an archipelago-nation of 400,000 people scattered across 3,000 small islands.

The Bahamas’ most populous island is the one with its capital, Nassau. The second-most-populous - and fifth-largest, and most-pretentiously-named - is Grand Bahama, home of Freeport, the archipelago’s second city.

Grand Bahama has a unique history. In 1955, it was barely inhabited, with only 500 people scattered across a few villages. The British colonial government turned it into a charter city, awarding the charter to Wallace Groves, an American whose Wikipedia article describes him as a “financier and fraudster” and includes section titles like “Suspicions”, “Legal Troubles”, “Investigations”, and “Allegations Of Underworld Connections”. He was . . . maybe the exact right person for the job, turning Grand Bahama into a Vegas of the Caribbean complete with casinos, jet-setters, swanky hotels, and a flourishing mob presence. Outside the glitzy center, a little heavy industry even managed to develop around the port. After twenty years, the charter zone was “the most modern, well-run, and prosperous part of the [Bahamas]”, and the population had increased to 15,000.

The golden age ended around 1970. The government, headed towards independence from Britain, became embarrassed by the private enclave and stripped away some of its rights. Around the same time, Florida liberalized its gambling regime, cutting off the flood of Floridians coming to play the slots. Control of the concession passed from Groves, to his business partners, to his business partner’s widow, and finally to a random collection of only mildly-interested heirs. Two big hurricanes in 2004 were the last straw. Grand Bahama is still a popular cruise destination, it still has a well-built port and surprisingly nice airport, and some of the old hotels still stand. But nobody would describe it as a happening place.

Now it’s back in the news. The government is increasingly tired of the heirs’ mismanagement of the island. They want it back. They made what they considered a fair offer. One of the heirs - the St. George family - seems to be on board. The other - the Hayward family - is less cooperative. The government is playing hardball by suing for $357 million of back fees which they say the heirs owe (the heirs deny that they owe this). The case is currently in arbitration. A likely outcome is that the court agrees the heirs owe some amount of money, the heirs can’t afford it, and they agree to sell back to the government.

Why does this interest us? The government has talked a big talk about the existing owners not doing enough to exploit Freeport’s economic potential. But the government also isn’t well-placed to exploit it. And they might need some extra cash to buy back control at a fair price. So rumor is that if the heirs decide to sell, instead of the government taking the island back themselves, they might choose to partner with one of the more modern Silicon-Valley-style charter city companies, and give them the charter. The legal agreement is already set up. They’d just need to change the name on the dotted line.

Put this way, Grand Bahama seems like a great deal. It’s a duty-free zone with one of the best deepwater ports in the area, making it an ideal center for trans-shipment - loading goods from one ship to another for various logistical and legal reasons. With its lovely climate, low prices, and proximity to the United States (50 miles from Miami), it’s well-placed to be a hub for digital nomads and remote work. Gambling is still legal there. Cruise ships visit regularly. And the beaches look like this:

See here for a more complete history of the island, and here for a Charter Cities Institute podcast on the topic.

California Forever, the project to build a new city in unoccupied land an hour from San Francisco, has overcome a first round of political headwinds.

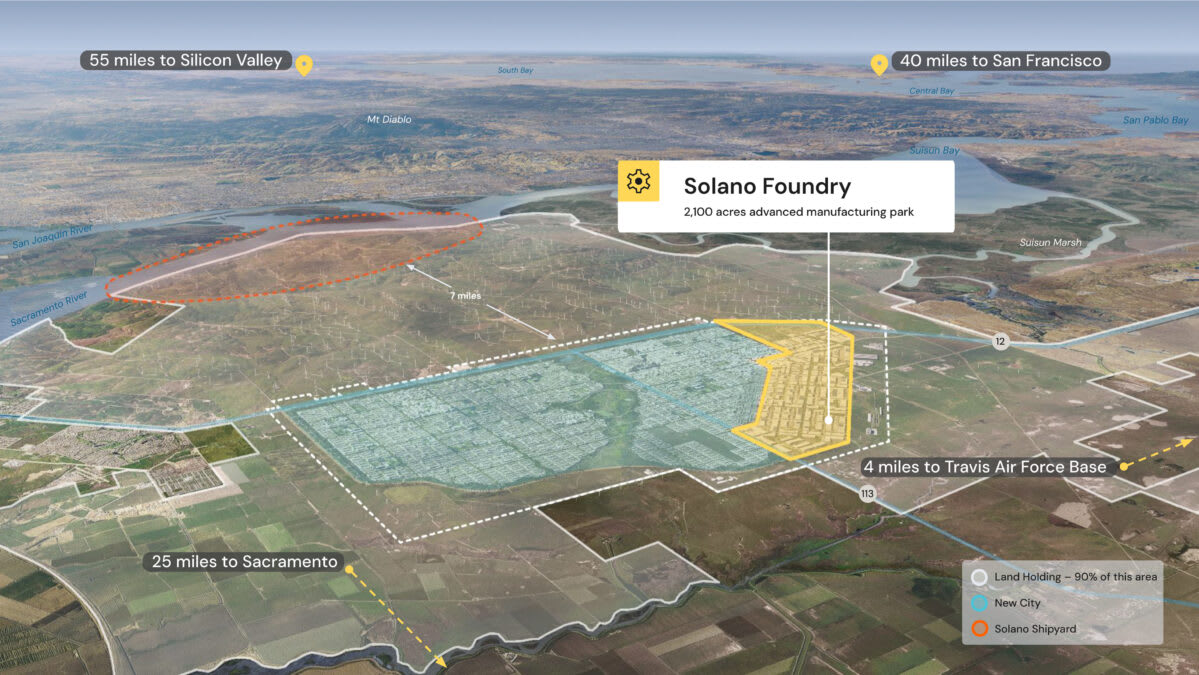

In 2023, a stealth mode company announced it had quietly bought up a city-sized tract of land in Solano County, and would be placing an initiative on the county ballot to let them build a futuristic planned community there. Enough local NIMBYs protested that the company and county jointly withdrew the initiative in favor of seeking some other agreement. In 2025, they announced their new strategy: they would partner with nearby Suisun City. Suisun would annex their land and permit development there, avoiding a county-wide referendum (they might also make a deal with another nearby city, Rio Vista).

The new plan is moving forward: earlier this month, California Forever submitted their annexation paperwork, which was deemed complete by the city. The remaining steps are:

Suisun City Council must approve their environmental impact report (may cause delays and added expense, but unlikely to block the project outright)

Suisun City Council must approve the annexation (city council has already voted in favor of California Forever before and will likely do so again)

The Solano County Local Agency Formation Commission - a county-level body of two supervisors, two local mayors, and a public member - must approve the annexation (may be complicated; lots of room for NIMBYs to cause problems here)

Period where locals in the area to be annexed may protest (there aren’t really any locals except some landowners who have already sold their land to the project, so legally relevant protests are unlikely)

The paperwork itself contains some exciting details. Phase 1 of the city will have 175,000 people, with the ability to expand up to 400,000 later. CEO Jan Sramek summarized the urban design as “American street grid, Spanish/Japanese superblocks, and Dutch woonerfs”. The American street grid is the logical right-angled design typical of cities like Manhattan or Chicago. The Spanish superblocks are the big blocks with courtyards in the center, typical of cities like Barcelona:

...and woonerfs are small Dutch side streets which are designed to just-barely-allow drivers but prioritize pedestrians. creating a road layer in between big car-centered thoroughfares and pedestrian-only sidewalks:

The proposal also moots two additional megaprojects: the Solano Shipyard, where the new city touches the upper tributaries of the San Francisco Bay. American shipbuilding has long been something of an embarrassment, the Trump administration is working on it, and the new city would be strategically placed to benefit if the federal government could remove some of the barriers that make US naval manufacturing unprofitable.

And the Solano Foundry would be the “the largest [advanced manufacturing] park in the US”. Many of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs’ manufacturing startups set up shop in Southern California - for example, Elon Musk’s original base for SpaceX and the Boring Company was in Hawthorne, near LA - just because the Bay has so few good industrial locations. The Foundry aims to change that, and aims for 40,000 new manufacturing jobs.

Finally, something nobody else will care about but which is close to my heart - Jan is pursuing a partnership with Monumental Labs, a group working on “AI-enabled robotic stone carving factories”. The question of why modern architecture is so dull and unornamented compared to its classical counterpart is complicated, but three commonly-proposed reasons are:

Ornament costs too much

The modernist era destroyed the classical architecture education pipeline; only a few people and companies retain tacit knowledge of old techniques, and they mostly occupy themselves with historical renovation.

Building codes are inflexible and designed around the more-common modern styles.

Getting robots to mass-produce ornament solves problems 1 and 2, and doing it in a model city with a ground-level commitment to ornament solves problem 3.

Sramek writes:

Our renderings do not tell the full story. Getting architecture right in a way that is also scalable and affordable is hard. And until now, we’ve been focused on the things “lower down in the stack” that need to be designed first – land use plans, urban design, transportation, open space, infrastructure, etc. But I started this company nearly a decade ago precisely because I felt that so much of our world had become ugly, and I wanted to live, and have my kids grow up, in a place that appreciates craft and beauty.

This is one of the clearest examples of what I love about model cities. There are lots of things that everyone (or at least a substantial proportion) of people want, which people aren’t doing - not because there’s some strong opposition or technical challenges, but because the system is too complex/diffuse/ossified to permit change. A lot of what I love about California is downstream of its geography as the westernmost part of the western world - the people who felt confined by Europe fled to America, and the people who felt confined by America fled to California, and until recently it was an open space big enough for new experiments to grow. I think of “California Forever” as a nod to that heritage, and a test of whether some of those sparks still survive.

In the 2010s, a conservative Honduran government decided to allow experimental “ZEDEs” - semi-autonomous charter cities - in the country. Several projects sprung up, most notably Prospera and Ciudad Morazan, and met some early success.

In 2022, the socialists took over and decided to end the experiment. They were able to ban the creation of new ZEDEs, but had more trouble disbanding existing projects. They found there were two legal roadblocks. First, the founders of the ZEDE system - well aware of how sudden shifts in governments could destroy charter cities - fortified their law with constitutional protections making it near-impossible to repeal. Second, they signed international treaties giving charter city investors the right to sue Honduras for very large amounts if it tried to destroy their hard work.

How do you repeal a law that says it would be unconstitutional to repeal it? The socialist-controlled Honduran Supreme Court tried their best, saying that the law had retroactively itself been unconstitutional, and so existing ZEDEs had retroactively been illegal the whole time. However, the court failed to remove the entire thicket of legal protection surrounding the ZEDE system; in particular, they did not strike down Article 94 of the Constitution, which said that unconstitutionality rulings could not be enforced retroactively. So as far as anyone can tell, the current status of ZEDEs is that it is illegal for them to exist, but also illegal for the government to take any action to remove them. On their way out, the Court ordered some penalties against “companies that became ZEDEs”, which is not really how this works (companies can found ZEDEs, but they don’t become ZEDEs; this is like saying “companies that became cell phones”) and which therefore nobody has tried to collect.

Why did the government’s case end so farcically? Honduras-watchers suggest that the Court was trying to balance its obligations to the government, to the integrity of the legal system, and to practicality. The government really wanted an anti-ZEDE victory to present to its voters. The integrity of the legal system made it hard to apply ex post facto judgments. And practically, the whole case ran up against the second layer of protections the ZEDE founders built around their project: the investor treaties. If Honduras were to end ZEDEs, ZEDE investors could sue in international court. Prospera’s investors have already sued for $11 billion - a third of Honduras’ GDP. The case is currently tied up in international courts, with the delay being amenable to both sides; the government expects to lose, and the Prosperans would rather keep the suit as a threat they can hold over the Hondurans’ head than actually get a judgment in their favor - which would be bad PR, and which they expect Honduras would not pay.

(also, although the Trump administration hasn’t taken a firm stance, Prospera seems like the sort of thing they would like, and Honduras is nervous about offending them too badly)

Since the government doesn’t seem to be able to legally shut down Prospera, they’ve resorted to harassing it - especially trying to debank it. This might have worked, if not for the fact that a certain $4 trillion weird Ponzi casino industry has always imagined itself as having a fig-leaf purpose of “what if a utopian libertarian island-city got debanked by a repressive socialist government and could only save itself if there were a entirely new kind of financial infrastructure totally different from the regular one?”; although I imagine they were just as surprised as anyone else when this exact scenario suddenly played out in real life, nobody can deny they were extremely prepared for it. So the attempted harassment has fallen flat too, and the government doesn’t have a lot of options.

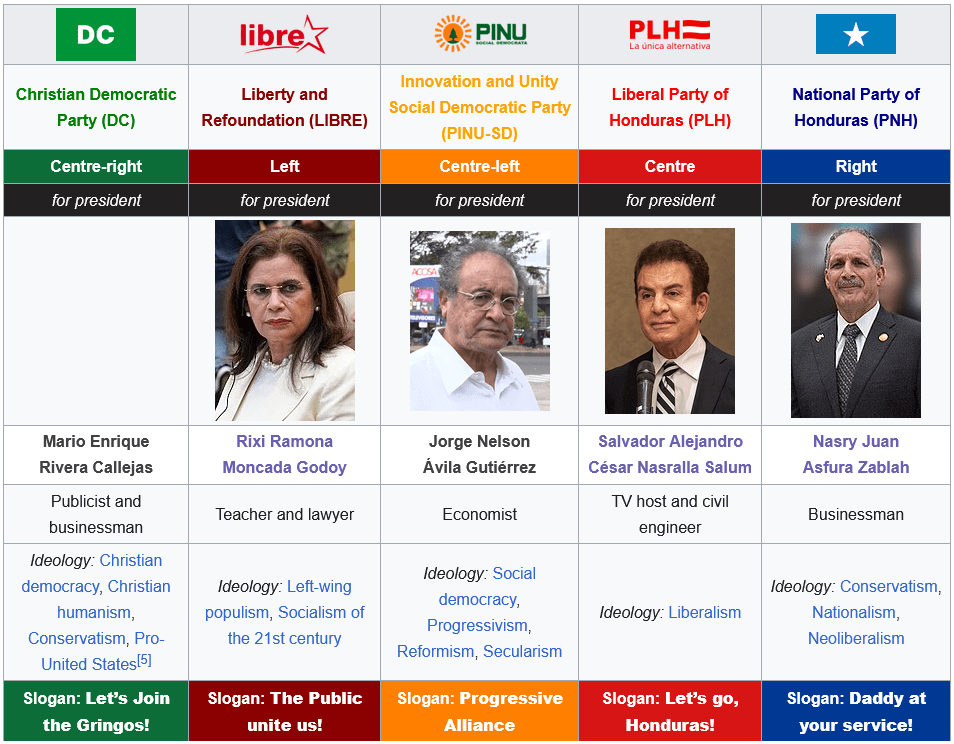

Further developments hinge on next month’s big election. The candidates seem like a colorful bunch:

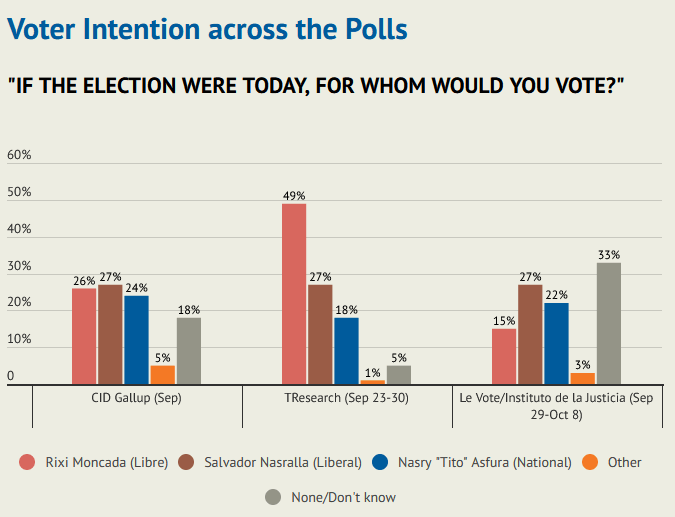

Polling has been contradictory:

…with Rixi Moncada (socialist), Salvador Nasralla (liberal), and Nasry Zablah (right-wing) all making strong showings. My impression is Moncada would be worst for Prospera, Zablah best, and Nasralla somewhere in the middle.

Meanwhile, my contact in Prospera reports that life in the city continues as normal, with most residents relatively insulated from the lawfare happening around them. They are up to 300 registered companies, a nearly-full office tower, a few residential developments under construction, and frequent conferences on relevant topics like crypto and biotech.

Sherbro, Sierra Leone. A place synonymous in the popular imagination with the phrase “Sherbro, Sierra Leone”. Population 30,000. Size 230 square miles (or “just a little bit smaller than Singapore”, according to its boosters).

Siaka Stevens is the grandson of Sierra Leone’s first president, also named Siaka Stevens. He grew up in Britain, worked in business and finance, then went back to his family homeland as an adult. Moved by the poverty he saw around him, he decided to start a charter city.

He recruited the help of Idris Elba, a famous British actor of Sierra Leonean descent, and together they started a company to build Sherbro Island City. The usual Dubai and Singapore comparisons were made. Maybe due to Stevens’ government connections, they got an impressively broad concession from the government - the Charter Cities Institute has compared it to Honduras’ ZEDEs, among the most autonomous charter city legislation in the world.

From the podcast:

Okay, so there are seven governing board members and the agreement specifically states that they are strictly from the private sector. SAP, our company, will choose four of the board members and the chairperson and the government of Sierra Leone will choose three. That’s the seven member board. And underneath that is a similar structure to municipal corporation. We have fiscal and legislative autonomy. English common law, very robust investor protections. The best way to kind of describe it, a similar situation, mean, Hong Kong now actually, and it’s a similar setup to Hong Kong and China’s relationship in the early eighties, where you have a special administrative region that is very autonomous, but sovereignty is held by the main Sierra Leone country. So it’s an innovative kind of new system of governance.

Stevens calls the island a “greenfield” site, but it includes a town (Bonthe, population ~10,000) and an ethnic group (the Sherbro people).

It’s slightly unclear whether Bonthe and other inhabited areas are within the SEZ, but it looks like maybe they are, and Stevens means he will mostly be building the new Singapore-style smart city on uninhabited parts of the island, with Bonthe as an early base for transit and development that he hopes will benefit but otherwise remain unaffected. Various local chiefs seem to be mostly in favor, as far as we know.

The big problem for these island charter city attempts is infrastructure. You eventually want heavy industry and high-value-add manufacturing, but how do you build up enough civilization - transit, power, labor, amenities - to support these expensive enterprises? Every charter city has its own solution - gambling in Grand Bahama, regulatory arbitrage in Prospera, political alignment in Praxis. Sherbro’s plans include:

A hub to lure the Sierra Leone diaspora back to the country (Google says the Sierra Leone diaspora is 336,000 people, most of whom are probably not digital nomads or jet-setters)

A place for African-Americans to come to reconnect with their roots (as a white person, I would not dare speak for African-Americans, so they will have to say for themselves whether their pride in their heritage takes the form of a desire to visit a mostly-empty island off the coast of Sierra Leone)

Tourism

A financial hub for the region (”Nigeria, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Guinea, Senegal . . . they’re all within a three hour flight radius of there”)

None of these sound very compelling to me, but sometimes you just have to survive long enough to find your true niche and pivot.

On the other hand, the history of African model cities backed by diaspora celebrities isn’t great. In 2022, the African-American rapper Akon said he was going to build a “real-life Wakanda” in Senegal called “Akon City”; also, it would be on the blockchain. To the shock of everyone involved, this did not work out, although there is a half-completed Welcome Center on the site.

1: As the Black Lives Matter movement spread across America in 2020, 19 black families came together to buy 98 acres and form the black separatist community of Freedom, Georgia. They don’t seem to have enough money for development, and as of the last update they were living in tents, but they may be saved in the most American way possible - someone wants to make a reality show about them.

2: On the other side of the, uh, aisle, the Return To The Land movement continues their plan to build a string of white separatist communities across the country, starting in the Ozark Mountains. They got a boost in July, when the Arkansas attorney general said the plan was not illegal.

3: Behind the scenes, the Trump administration continues to work on its plan to create “Freedom Cities” - Trump-branded charter cities on federal land across the United States. Firm information is rare, but new suggestions include Belle Isle in Detroit and some sort of partnership with the company behind Prospera.

4: New special economic zone in Nevis called Destiny, with the usual breathtaking renders, crypto connections, and ambition to be “the Monaco-Dubai of the Caribbean”. But why not “Monaco-Dubai-Singapore”? Come on, be ambitious!

.png)

![The Violators by Censor Design – C64 2025 [video]](https://www.youtube.com/img/desktop/supported_browsers/chrome.png)