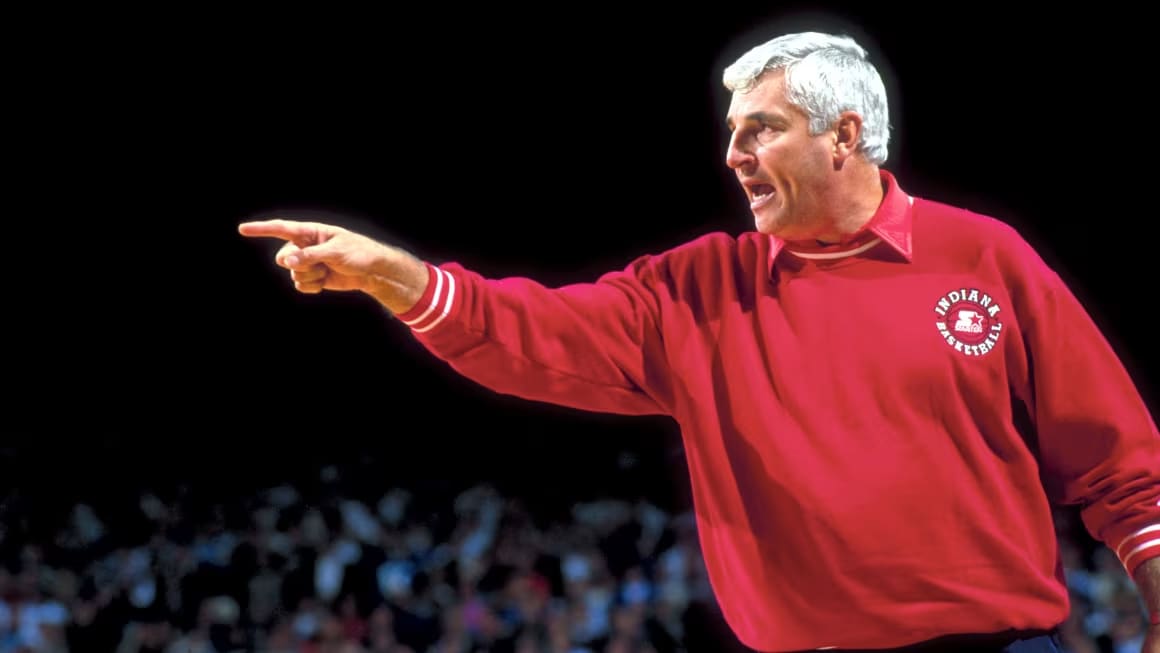

I’ve spent the better part of a week meandering through a biography of Bob Knight, one of the few coaches to lead a men’s Division I college basketball team to an undefeated season. Knight’s 1975-76 Indiana Hoosiers went an impeccable 32-0. There’s a certain weight to that record; nearly half a century later, no team has reached this level of perfection.

In the face of such a singular achievement, it’s tempting to cast all light on Knight himself—his genius, his gifts, his once-in-a-generation talent. But doing so obscures the scaffolding behind his success: the network of mentors who prepared him for greatness.

Early in his biography, Knight takes pains to note several coaches who influenced him—coaches like Harold Andreas of Cuyahoga Falls High School and Clair Bee of Long Island University.

These aren’t household names with ESPN documentaries. Their Wikipedia pages are either thin or nonexistent. Yet Knight credits each as essential to his development as a coach. In doing so, Knight reminds us of a truth we tend to forget: successful people often have less-than-famous mentors.

This blind spot extends far beyond the world of sports. Most of us know Steve Jobs, but fewer know how deeply influenced he was by Regis McKenna. Greatness, more times than not, rests on the shoulders of such invisible giants.

And yet in our contemporary search for counsel, we’ve been conditioned to tune out these quieter voices.

The notion that greatness rests on invisible shoulders stands in direct challenge to the prevailing model of mentorship today. In Knight’s time, you sought out a teacher—often someone obscure but with a proven record of competence—and you learned at their side. Mentorship was anchored in demonstrated mastery.

Today, however, mentorship for many begins not with a person, but with an algorithm. In a world of infinite content and finite attention, we’ve come to rely on proxies—social proof, follower counts, the seductive gloss of high production value—to help us screen for wisdom. And while, on the surface, these signals seem right and feel good—the dopamine keeps us convinced—these proxies ultimately mislead us, causing us to conflate visibility with value.

Without realizing it, we fall into the trap of assuming expertise guarantees an audience, forgetting that digital platforms are designed to reward those who invest in being found—not necessarily in being good. As a result, we stunt our own growth by believing the best teachers are always the most prominent ones.

But the algorithm, for all its alluring power, is not inescapable. Knight’s story suggests a path to reclaiming agency over our own development. But this requires a conscious rebellion of sorts—an opting out of what the feed serves us in favor of the more disciplined work of assembling our own mentorship. This is a practice that rests on three steps.

A few years into his career, Knight was offered a head coaching position overseeing not just basketball, but football as well. Having played both sports, Knight was qualified. But he ultimately turned the job down.

Why?

Knight understood something critical: the role would have diluted his focus. Knight’s ambition was not merely to coach, but to be world-class at coaching basketball, and he recognized that any other pursuit, no matter how tempting, would be a distraction from that central mission.

This points to the first step in assembly: define your domain.

It’s a step many of us skip. But all meaningful learning, like any meaningful endeavor, begins with constraint. By narrowing his scope, Knight could devote the full measure of his time and attention to one thing. This singular focus enabled a kind of accelerated growth—a speed of learning that could only come from deep, sustained immersion.

Our conception of mentorship tends to lionize the singular genius—the master who has scaled the mountaintop and stands alone. And so we search, in turn, for that one perfect mentor who embodies everything we hope to become.

But Knight’s story suggests a different, more practical path. Recall the coaches he credited—Andreas and Bee. Neither of them ever held up an NCAA championship trophy. One was a high school coach in a small Ohio town; the other, as I understand it, never even coached in the tournament that would later define Knight's own career.

So why then would Knight, a man with such vaulting ambition, seek their counsel?

Because of their mastery of the fundamentals. Knight understood that he didn't need mentors who were champions, but craftsmen. He recognized that “coaching basketball” wasn’t a single, monolithic talent, but a collection of discrete skills:

Teach the mechanics of a jumpshot

Manage a locker room at halftime

Counter a man-to-man defense

Recruit a five-star prospect

This points to the second step: deconstruct your craft.

Instead of searching for one perfect teacher, you assemble your mentorship modularly. Break down your chosen domain into its component parts, and then find masters of each. This is the very essence of the modular approach.

The power of this shift in perspective cannot be overstated. It reframes the entire enterprise of finding a mentor. Our screening criteria changes entirely, from the question, “Who has achieved everything I want to achieve?” to the far more practical and immediate one: “Who has mastered the specific skill I’m struggling with right now?”

Seen in this light, apprenticeship no longer requires the single, perfect guide. Rather, it becomes the work of assembling your own faculty—a mosaic of mentors, each a specialist in one part of your chosen discipline.

So, having defined a domain and deconstructed it into its discriminant parts, a final question arises: if not through the algorithm, where does one find these mentors?

The answer, I’ve found, requires different kinds of work.

First, trace the lineage. True masters are rarely self-made. Greatness has a genealogy. You can find it in the footnotes of a book, in the heartfelt thanks of a reward speech, in the passing comment of an interview. Your task, then, becomes that of an archaeologist: to follow the trail—to study not only your heroes, but the heroes who shaped them.

Second, seek out the practitioners. Go to the people who are doing the work, quietly and well—and ask of their library. Pull aside the head chef and inquire which cookbook they might save in a fire. Ask the CTO who taught them to code with such clarity. The reading list of a master, I’ve found, is more reliably grounded in utility than optics.

Finally, go analog. There is a world of wisdom that exists beyond the internet. It lives on the dusty shelves of bookstores and libraries, in out-of-print textbooks and forgotten memoirs. The algorithm can’t index what isn’t online. This is where true alpha often lies: in obscurity.

Bob Knight’s undefeated season didn’t spring from a vacuum. It was the culmination of a long and deliberate discipline—of defining a domain, deconstructing a craft, and following the trail back to the foundational sources of wisdom.

A few questions to leave with:

Look at your calendar for the last month. If a stranger had to guess what your primary domain is based only on this evidence, what would they conclude? Does this align with your self-described focus?

What are you currently doing out of habit or obligation that no longer serves your core mission?

Choose one visible expert you admire in your field. Can you spend 30 minutes this week researching one of their key influences—an "invisible mentor" who shaped them—and identify the specific skill they likely learned from that person?

What is the most important book in your field that was published before 1980? Have you read it?

Who is one mentor from your past who taught you something valuable? Can you, this week, send them a thoughtful note—not just saying thanks, but reminding them of that lesson?

.png)