July 20th, 2025 marks the 56th anniversary of the moon landing.

Today, the Apollo program is remembered by Americans with pride and reverence, a nostalgic symbol of American exceptionalism. Yet, before that "giant leap for mankind" Americans weren't so enthusiastic…

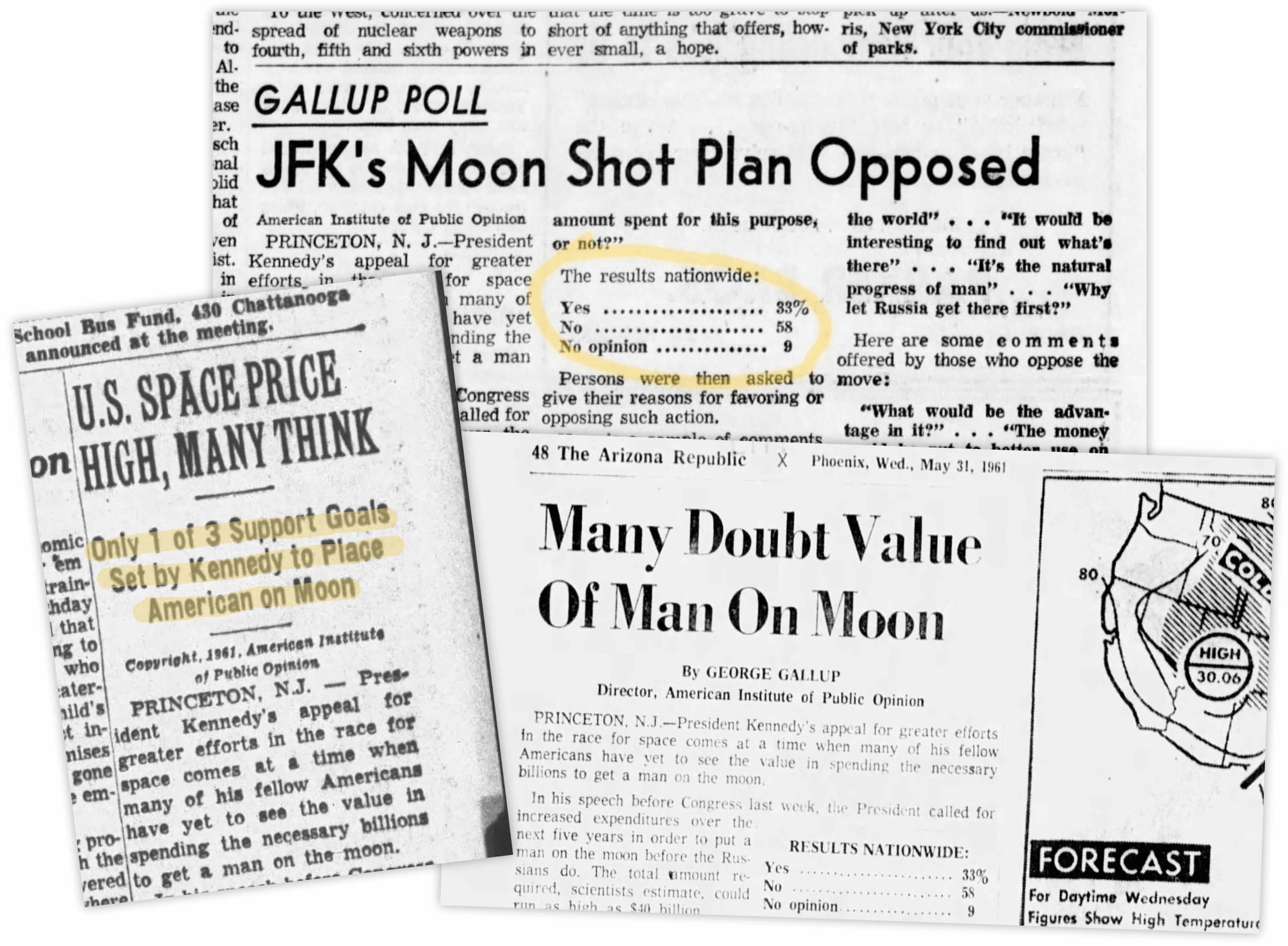

After President Kennedy’s 1961 declaration to put man on the lunar surface by the end of the decade a Gallup poll revealed only 33% supported, compared with 58% opposed:

This, despite Alan Shepard Jr. recently becoming the first American in space. Aggregations of opinion polls through the 1960s have shown disapproval of the moon landing was consistently higher than approval.

Popular opposition isn’t something you often hear about regarding the Apollo program. It is conveniently missing from America’s collective memory, in lieu of a tale of collective patriotic triumph. A narrative that appeals to Democrats as an example of successful big public programs - and Republicans - as a triumph of the capitalist west against the communist east.

The truth is, opposition was a constant, and even continued after man set foot on the lunar surface. Dr. Norbert Wiener - the ‘father of cybernetics’ - would coin the term ‘Moondoggle’ for the program in 1961, a neologism that would be adopted by Republican’s like Barry Goldwater (and a 1964 book of the same name.)

President Kennedy’s own head of Science Advisory Committee - Jerome Wiesner - opposed a manned mission, releasing a critical report on the notion before Kennedy had even been sworn in, or made his declaration.

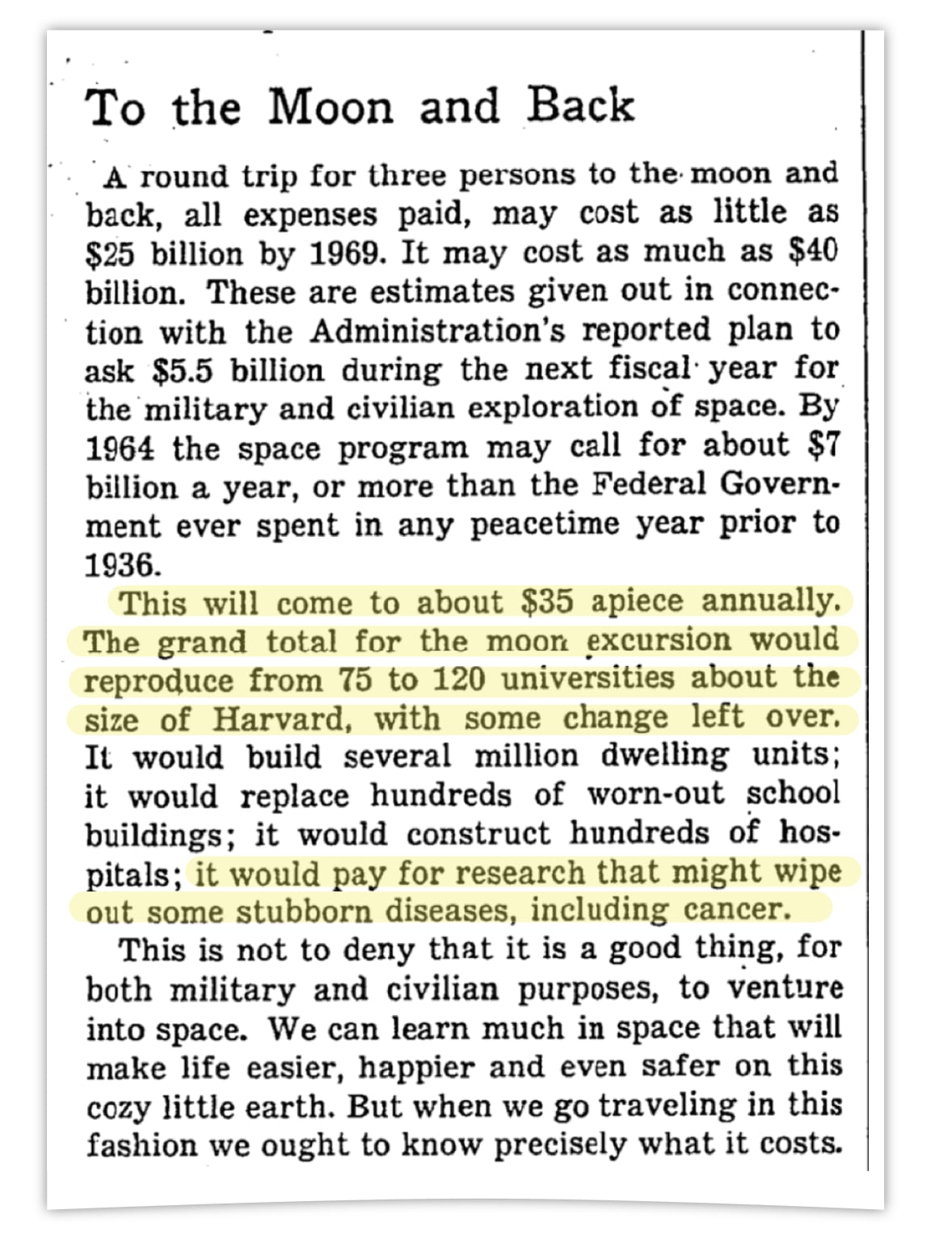

In January 1962 The New York Times would note what else such a budget could afford the American people: over a hundred universities, millions of homes, hundreds of hospitals and cancer research. These concerns would be echoed by left wing opponents to the program, later memorialized in Gil Scott-Heron’s spoken word poem ‘Whitey on the Moon.’

In September, 1962 President Kennedy gave his famous Rice University speech where he spoke those famous words: “We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.” This no doubt helped sentiment towards to mission.

However by November that same year Kennedy was expressing concerns privately about public sentiment saying “We’re talking about these fantastic expenditures which wreck our budget, and all these other domestic programs are starving to death”, suggesting the cost could only be justified if framed in the context of military superiority over the Soviet Union.

1963 would really see opposition heat up. Former President Dwight D. Eisenhower - whose administration initially created and funded NASA - expressed his own reservations, dismissing Kennedy's lunar ambition as "almost hysterical" quipping:

“Anybody who would spend $40 billion in a race to the moon for national prestige is nuts…”

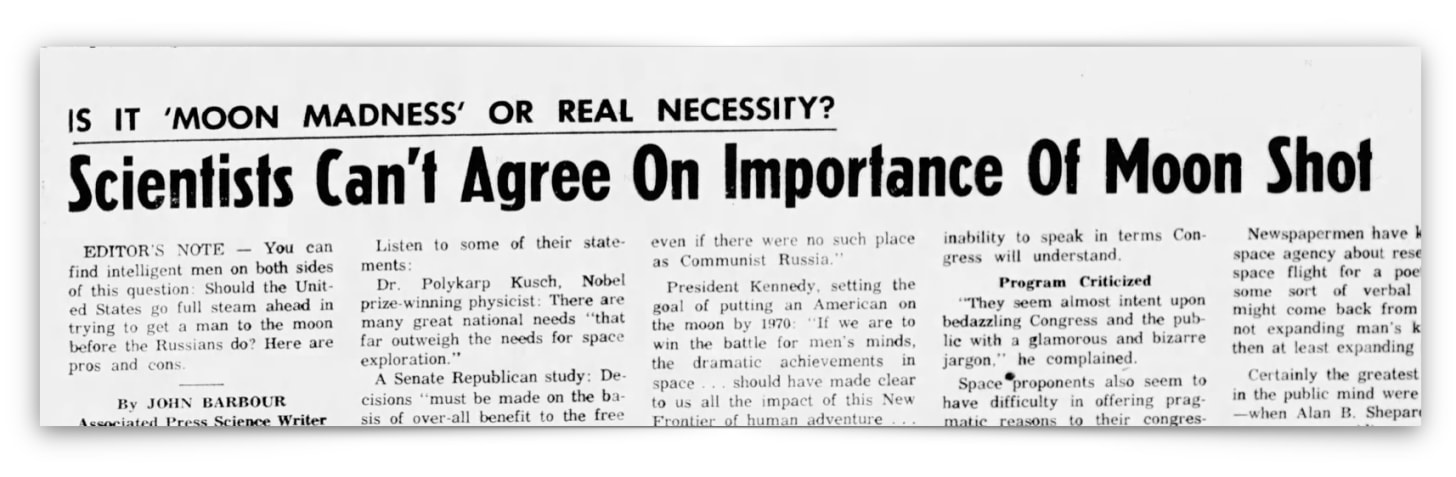

Kennedy would shoot back, noting the previous administrations record deficit spending. Some in the scientific community would push back too, a newly appointed editor of the prestigious journal ‘Science’ - Philip Abelson - would pen a critique of the mission - saying it was a moral outrage to not instead focus research expenditure on something like Cancer research. The Washington Post would cover Abelson’s criticisms, followed by a 3-part series in the same spirit titled ‘Moon Madness?’

In September 1963 President Kennedy would again voice his concerns about public perception - especially since he was up for re-election the following year, saying to NASA head James Webb, "But this looks like a hell of a lot of dough to go to the moon” conceding that much could be achieved with an unmanned mission. Through the conversation Webb would insist it would be worth it in the end - with Kennedy affirming this notion:

"I think in time, it's like a lot of things; this is mid-journey and therefore everybody says, 'What the hell are we making this trip for?' But at the end of the thing they may be glad we made it."

Months later Kennedy would be assassinated - he wouldn’t live to see his moonshot manifest, but despite continued resistance to the moon mission the Apollo Program would eventually succeed.

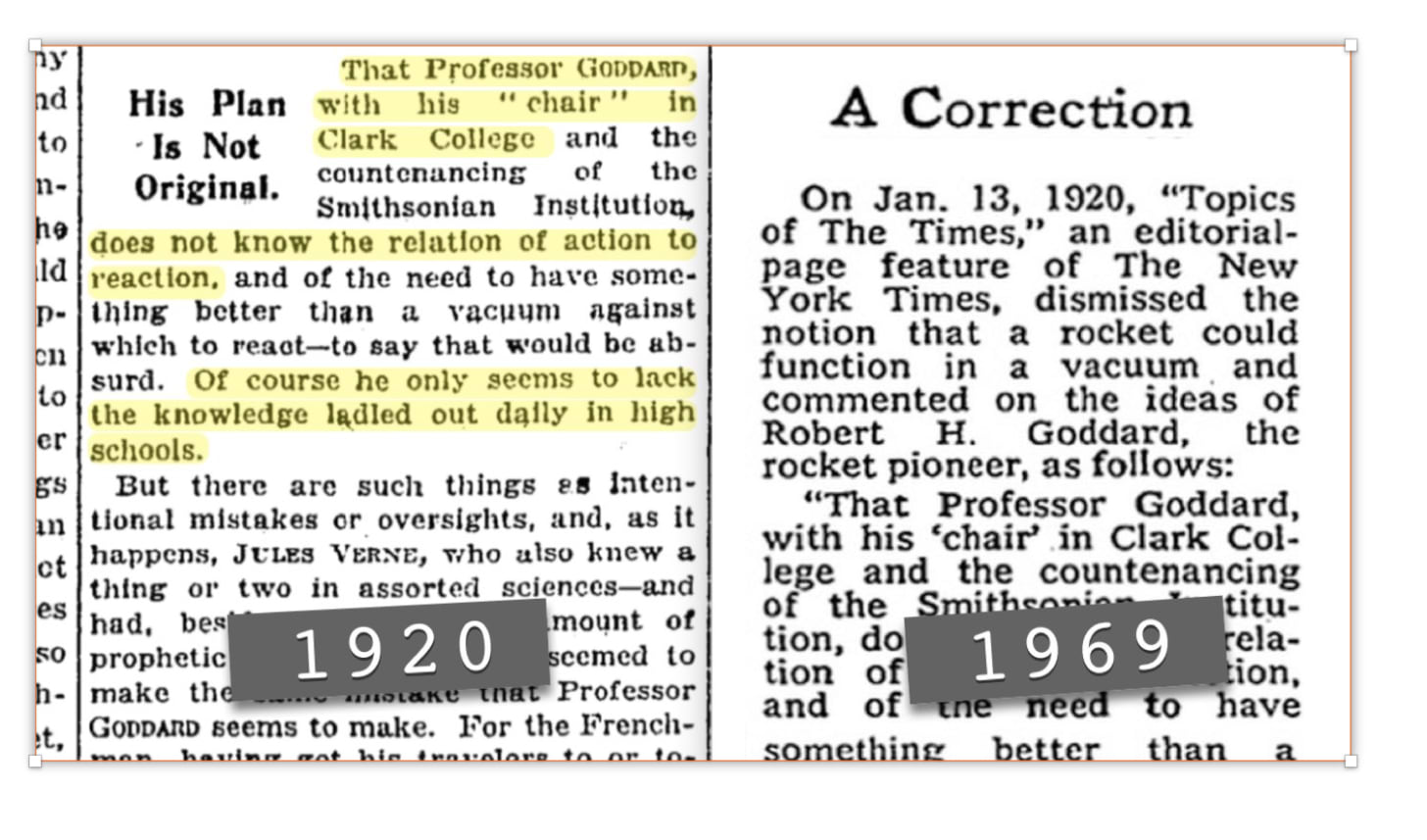

As author of ‘One Giant Leap’ Charles Fishman noted when the landing eventually happened The New York Times would devote 18-pages to the moon walk. This the same paper who implied the mission was a waste of money, and deemed space travel impossible in 1920 - something it would issue a correction for as Apollo 11 approached the moon:

Once skeptical Barry Goldwater, would call the Apollo crew “the only national heroes we have” crediting them with “giving inspiration and hope to the young people of our country.”

In the end most Americans are “glad we made it” - as Kennedy predicted - but it took a while, only four years later the Apollo program was defunded. Only 47% said it was worth it a decade later in 1979 and it would take 20 years for this number to reach 77% in 1989. Meanwhile opposition to further moon missions remained higher than support until at least the mid-1990s. The US hasn’t been back to the moon since 1972.

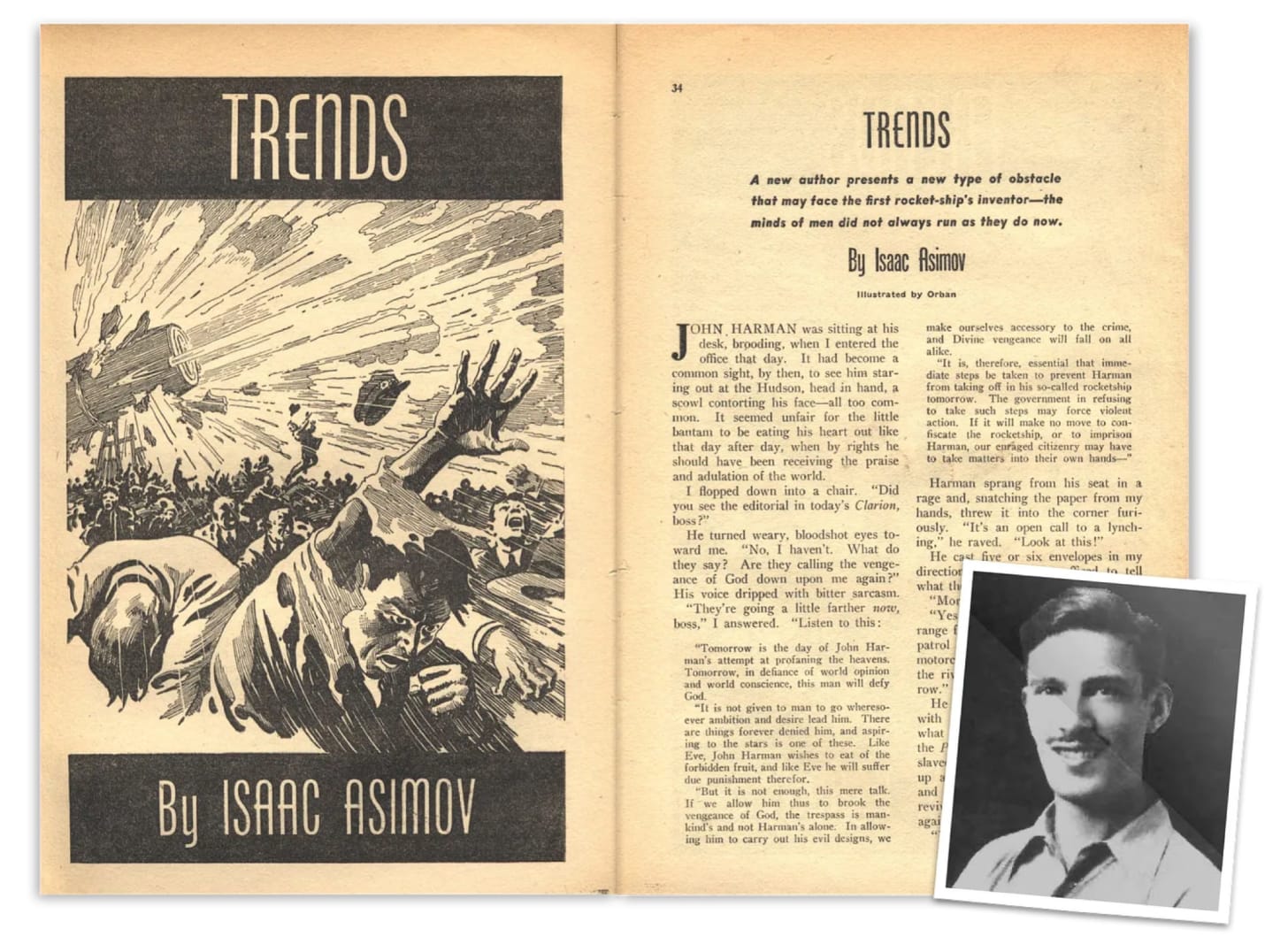

In 1974, Isaac Asimov would reflect on the recent opposition to space exploration, referencing his 1938 short story ‘Tends’ in-which he foretold the resistance in a narrative about the first space mission, saying of the story:

“It never occurred to anybody that there might actually be resistance to the whole notion; people might think it was a rotten idea and a waste of money.”

The only difference being his story involved a private space entrepreneur - John Harman - trying to reach space rather than a nation state. A seemingly unbelievable prospect even in 1979, not so anymore.

.png)