It’s like snapping your fingers and watching a dragon spring to life—hulking and graceful all at once.

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

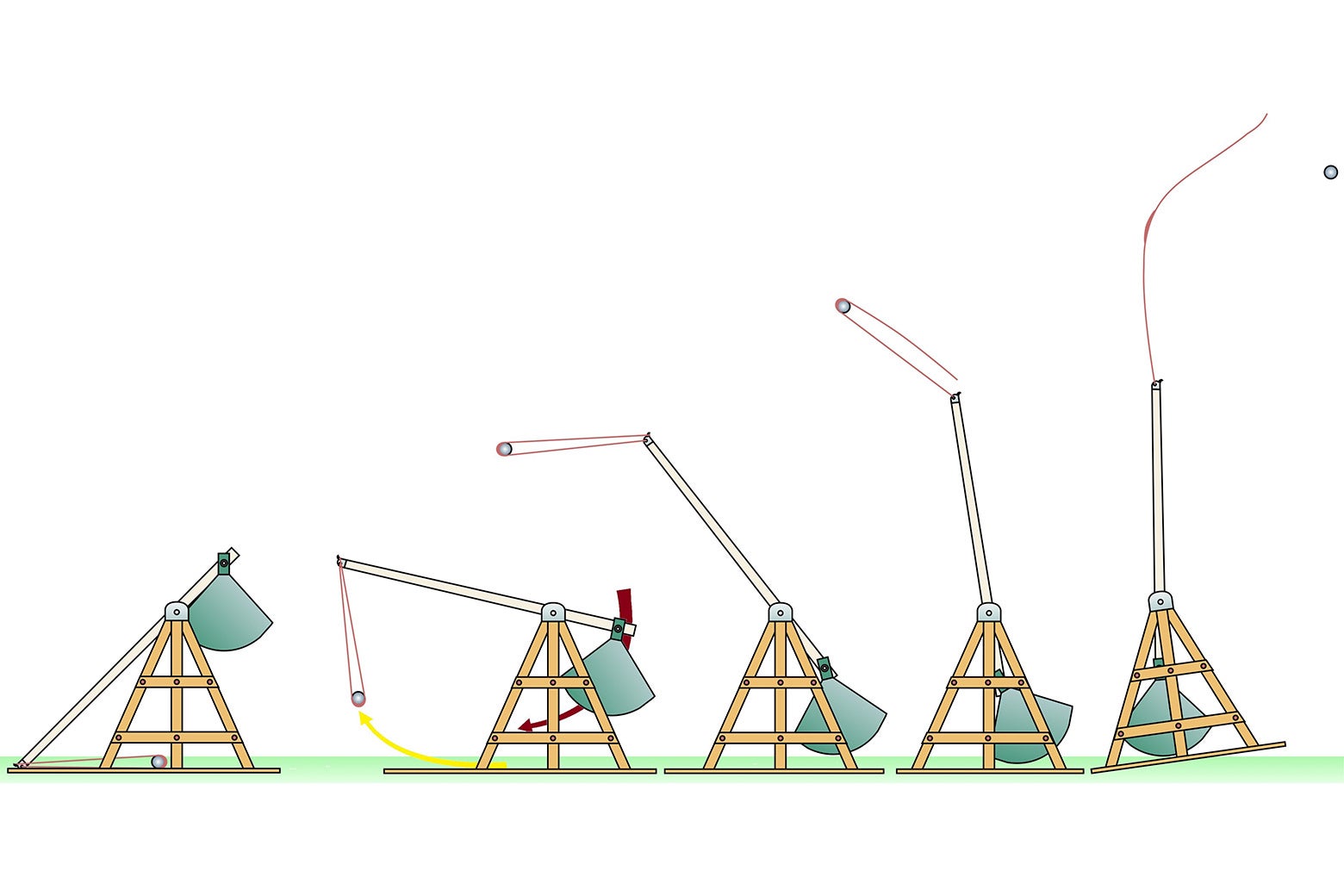

The trebuchet was the most fearsome weapon of medieval times, a giant catapult that could lay waste to any fortress by battering its walls with boulders. It’s funny to think, then, that in terms of the physics, trebuchets (“treh-byu-shays”) were little more than children’s seesaws: You raised a counterweight on one end, let it drop, and used that force to fling a projectile from the other end.

Of course, trebuchets differed from seesaws in a few ways. Instead of the pivot being in the middle of the beam, it was shifted toward the weighted arm. This lengthened the opposite, throwing arm for more leverage and speed. A sling attached to the throwing arm added extra juice by lengthening the arm even more. Modern re-creations of trebuchets have hurled boulders 125 miles per hour.

By Sam Kean. Brown, Little.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

History’s biggest trebuchets, from the 1300s, took months to build. They stood over 60 feet tall, used counterweights of 33,000 pounds, and could toss a 300-pound boulder 300 yards. At times, however, generals got creative and flung other things. By aiming above a wall, they could pelt the town behind it with beehives, scorpions, snakes, flaming pitch, rotten vermin, or excrement. One historian told me in an interview that, for a small trebuchet, “a good size projectile is, morbidly, a human head.”

Sadly, zero medieval trebuchets survive today. (One turned up in 1890s Prussia, when people unearthed it during the demolition of an old church. After spending several minutes marveling, they hacked it up for firewood.) The best way to study these fearsome weapons, then, is through a field called experimental archaeology.

Experimental archaeologists actively re-create the past. I recently spent several years chronicling this rogue branch of archaeology for a new book called Dinner With King Tut. For different chapters, I attended an authentic Roman banquet, brain-tanned deer hides, sailed on an ancient Polynesian ship to learn old navigation methods, talked to people who made replica Egyptian mummies in modern times, and got (and gave) my first tattoo, among other things. I also spent an afternoon in Utah firing a replica trebuchet constructed by trebuchet fanatic Daniel Bertrand.

Bertrand’s a tall, earnest fellow with a shaved head, a mustache, and a toothy grin. He says “man” a lot as emphasis. (“Good idea, man.”) He first learned of trebuchets while attending Utah State University, whose engineering school holds a contest every fall where students build trebuchets with modern materials and chuck pumpkins. A history major, Bertrand had never even used a power drill before, but after watching the pumpkins fly, he became obsessed with trebuchets and decided to build an authentic medieval one. Looking back on his first trebuchet, Bertrand laughs and admits he had no idea what he was doing. “It was sketchy, man. Someone could have gotten hurt.” (Poorly constructed trebuchets did kill people in medieval times—often to the delight of those watching from the besieged fortress.)

Bertrand has since built several more trebs, including one that stands 33 feet tall. Historically, engineers named their trebuchets, like battleships: War Wolf, Victorious, the Bad Neighbor. Bertrand initially named his the Black Widow, after finding a spider in the lumber used to build it, before switching to the Sentinel.

The Sentinel sits in a grassy field amid cattle ranches in northern Utah; snow-capped peaks loom in the distance. I arrive on a warm Saturday in October, one of those sunny, deep-breathing afternoons that make you wonder why you don’t live in the mountains year-round. A crowd of 20 has gathered to see the Sentinel fire. It’s nearly Halloween, so two girls are dressed as a witch and a red-headed fairy; there’s also a thirtysomething man in a puffy Tudor hat, doublet, and hose. A fuzzy white labradoodle darts around clawing holes in the dirt.

Bertrand is wearing a fluorescent yellow T‑shirt that’s filthy with tar. He’s joined by his trebuchet-firing crew—young dudes in dirty jeans with chew-can rings worn into the back pocket; most study history or classics at Utah State.

I tip my head back and study the Sentinel. Its throwing arm, currently at 12 o’clock, weighs 360 pounds and is not hewn or sanded; knots are visible in the wood. (In medieval times, engineers sometimes left the bark on.) Opposite the throwing arm, at 6 o’clock, hangs the counterweight, a teardrop-shaped wooden bin 10 feet tall. It weighs 500 pounds empty, and currently holds 1,400 pounds of sandbags. The throwing arm and counterweight are supported by two A‑frames whose barn-red paint has faded. Miles of tarred rope bind everything together. When under stress, the ropes ooze tar, which attracts bees.

The Sentinel’s target stands two and a half football fields away: a 20-by-16-foot wall made of pallets, plywood, and old cabinet doors that Bertrand nailed together and propped up with four‑by‑fours. I think of it as a faux fortress. The 250 yards is a typical distance for castle-bashing, since the archers defending such strongholds struggled to hit targets much beyond that distance.

Firing a trebuchet involves dozens of steps, but the basic idea is simple. First, the counterweight gets raised to store energy. Three of the dudes and I begin ratcheting it up by turning two large wooden X’s attached to a thick rope. It’s beastly work. We crank and crank and crank, stroke after stroke, straining like Atlas against the 1,900-pound counterweight. And with each turn of the X, it rises maybe one inch. Before long, my arms are burning and I’m sweating. My abs ache the next day.

Lifting the counterweight simultaneously lowers the throwing arm, and after 10 long minutes of cranking, the counterweight has been raised to 10 o’clock and the tip of the throwing arm is nearly kissing the ground. We lock the arm into place with a metal pin attached to a cord, then load the ammunition. Bertrand often flings bowling balls—flaming ones on New Year’s Eve—but today we’re launching spherical garden stones. Each weighs 20 pounds. For fun, Bertrand has drilled holes into one of them so it whistles as it flies.

Attached to the far end of the throwing arm is a rope-and-leather sling. We stretch it along a wooden trough on the ground beneath the frame and wrap it around a garden boulder. When the treb fires, the throwing arm will drag the sling and boulder down the trough, then whip them up and around, flinging the stone at the faux fortress. It takes a good 15 minutes to prepare each shot. When everything’s finally ready, Bertrand hands me the trigger cord and tells me to pull.

Every person who fires the treb that day—yours truly emphatically included—gushes the same thing afterward: “Boy, that was satisfying!” The firing pin holds thousands of pounds of tension in place, and it takes a hard, full-body tug to release it. But when it goes, my God. It’s like snapping your fingers and watching a dragon spring to life—hulking and graceful all at once. The counterweight plummets. The throwing arm flies up. The sling whips over the top with a whoosh. Then the garden boulder absolutely snaps into the air, as if Hercules hit it with a pitching wedge. It soars upward and hangs there for four seconds, six seconds, eight—a black meteor arcing against the blue sky.

Then 250 yards away, there’s a splash of dirt, and we all gaaah in unison. I almost don’t care that it missed the wall. Knowing I did all that with one little tug was magic enough.

Bertrand, however, wants to smash the wall. We reraise the weight and reload the sling. He lets the witch and fairy pull the trigger cord this time; they yank so hard they topple onto their keisters. But downrange, it’s another miss, another splash of dirt.

The ball is sailing high and left. To adjust the aim, Bertrand starts tweaking different components, and it soon becomes clear that aiming a trebuchet is more art than science. There are so many variables to consider: the mass of the counterweight, the mass of the boulder, the angle of release, the tension on the sling, the length of the sling, the presence or absence of wind. One dude jokes, “If only I remembered any trigonometry, this would be easy.” We chuckle, but after reflection, I think he’s wrong. This is way harder than trig.

Ultimately, Bertrand removes a 50-pound sandbag from the counterweight bin, tightens the sling, and realigns the wooden trough. We load for a third shot. My arms are noodles now from turning the ratchet wheels. Doublet-and-hose dude steps up to pull the trigger. The garden ball leaps up—and floats mere inches over the wall. Drat.

The fourth shot misses right. The red-headed fairy cackles, “Your hard work didn’t pay off!” The rest of us groan. The novelty of flight has worn off. We want a hit.

Finally, around 1 p.m., we load up for a fifth shot—and nail that bastard. Fist pumps galore. But it struck the fortress wall low, about knee height. To really rattle their teeth in there, Bertrand adjusts a pin that controls the sling’s release point, to nudge the ball higher. We hold our breath as we send the sixth shot aloft.

Due to the distance, we see what happens before we hear anything. A black blot suddenly appears on the wall, as if someone hurled an inkpot. Then a bang, like a kernel of burst popcorn. We erupt in cheers, and run downrange to inspect the carnage.

There’s a giant hole in the plywood, and we stick our arms through like a magic trick. But the real delight comes around back. Two thick four‑by‑fours—house timbers—have been splintered, and there’s wood shrapnel sprayed all over the grass, like in news footage of tornadoes. Trebuchets truly are forces of nature. We can sense our enemies trembling.

Instead of trudging back to the treb for the seventh shot, a few of us linger downrange, about 30 yards to the side of the wall. I fall to chatting with a young married couple, Andrew and Kaeli. Andrew built his own metal trebuchet at Utah State years ago; he shows me video of hurling a pumpkin at a derelict piano.

“How’s life in northern Utah?” I ask.

“I love being in the mountains,” Andrew says. “Great scenery, so many cool hikes. Plus, we can blow up microwaves in the gorge.”

“You, uh—what?”

“Blow up microwaves, using Tannerite.” (I google this later.

It’s an explosive.)

“Oh. Why microwaves? Just because they’re strong and confined?”

Andrew nods. “Microwaves, ovens, stuff like that.”

Kaeli adds: “We got the shrapnel really high with our last microwave.”

At this point the trebuchet crew waves their arms, alerting us that they’re about to launch. We settle in to watch.

The sling has whip-cracked before, but the noise seems more ominous now, with the shot coming at us. We can see and hear the ball better, too, screaming down like a hawk. It’s another direct hit, and my knees buckle at how loud the smack is. From the uprange, firing side, trebuchets are all majesty. From the fired-upon side, you appreciate the violence.

Overall, we smash the wall half a dozen times. But there are plenty of misses, too, and at 3 p.m., Bertrand rallies us. “I want to end on a hit, man.” One more good smack, and we’ll go home.

Guess how many times we hit the wall after that. Sometimes we miss right, adjust for that, then miss farther right. Sometimes we miss right one throw, adjust nothing, and miss left the next one. Bertrand continues to tinker, and as the misses pile up, I revise my earlier opinion: Aiming a trebuchet is neither art nor science; it’s voodoo. Bertrand half-blames our bad fortune on him forgetting his lucky hat. Someone else suggests summoning a priest and holy water. But no matter how much juju we employ, we keep missing—just high, just low, just right.

To be fair, had this been a proper fortress, the just-lefts and just-rights would have been hits, and the just-highs would have clobbered the town beyond. But with the sun starting to dip behind the mountains, we finally give up, and leave the Sentinel to keep watch for the night.

Excerpted from the book Dinner With King Tut by Sam Kean. Copyright © 2025 by Sam Kean. Reprinted with permission of Little, Brown and Company. All rights reserved.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.

.png)