Serenity Strull/ Getty Images

Serenity Strull/ Getty Images

(Credit: Serenity Strull/ Getty Images)

Slowly but surely, huge swaths of the internet are vanishing. But the artefacts of the early web are still out there, and they have lessons for the future.

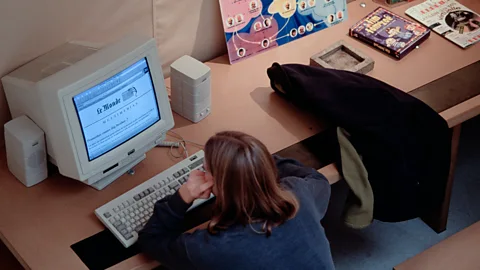

When my family got our first computer in 2003, I watched in awe as the components were set up the living room. Our wooden desk groaned under the weight of the hefty monitor. The computer tower left dents in the carpet. The future was here. And it was big.

But it was more than just a computer. It was a portal to a new world for me – a way to access something called the internet.

My parents let me log in for one hour per day. My early excursions in cyberspace left me feeling like a pioneer chopping through bushes in a strange land, browsing esoteric websites with bad graphics, message boards and clunky Flash games. At night, I snuck downstairs to boot the computer back up, looking over my shoulder at every creak of an upstairs floorboard.

But these days the internet can seem mundane by comparison. I have 24-hour access, and my go-to sites are dreary and familiar: social media platforms that can feel better suited for doomscrolling than exploration. Algorithms lead the way, like a strict tour guide on sanctioned trails cut through a once enigmatic wilderness.

So a few months ago, I went in search of some of the earliest corners of the web to see how much of it still there and find out what it has to teach us.

The web you and I know may be ending. Because of AI and some radical changes to Google Search, some worry the tools that used to send us to websites will simply give us the answers we're looking for instead. If fewer people visit websites, it could be harder for sites to make money. Some experts fear we've entered a new era that could derail the economic system that encouraged people to create websites in the first place. It's likely that this chapter of digital history is closing.

In a world of polished, algorithmically optimised content, the old web is a testament to individuality and experimentation.

We've lost alarming amounts of our digital history. Some 38% of webpages that existed in 2013 are no longer accessible, according to the Pew Research Center. Niels Brügger, a professor in media and internet history at Aarhus University in Denmark, began noticing it as early as the 1990s. "The average lifetime of a website, it's around a couple of months," he says. (Read more about why there is so little left of the early internet.)

This decay has been happening since the web was created. But the older, simpler, stranger net hasn't vanished yet. Ruins of a bygone internet live on, waiting to be explored. You only need to know where to look.

There's no better place to start than the world's first website, info.cern.ch, built by the researchers who invented the World Wide Web. Today, it's dedicated to the history of the web itself. But you can also experience the first website as it existed back in 1992, thanks to a tool that simulates the first readily-accessible web browser, called the Line-Mode Browser. It's text only, and you couldn't even use a mouse in its original iteration. To visit pages about bioscience, for example, you typed the number three.

"The web existed in the early '90s, but it really was academic and had a very small user base," says Ian Milligan, associate vice-president of research, oversight and analysis at the University of Waterloo in Canada, and a historian who studies web archives. If you want to see the dawn of the modern web, he says you should start in 1996. "That's when the web really begins to pick up as the central communication medium for Western society and then international society," Milligan says.

Today, the website for the Liberal Party of Canada, the country's leading political party, is a slick and modern affair. Look back to an archived copy of the Liberal's very first site, however, and you'll find a different atmosphere.

"Welcome Cybernauts!" reads a message posted in October 1996, greeting visitors on behalf of then Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chrétien. "We Liberals are excited about the potential of the World Wide Web... the potential for interactive communication with you!" There's a similar tone on the site for former US Senator Bob Dole's failed 1996 presidential run.

With tools like the Internet Archive, the popular websites of today offer windows into the internet's distant past (Credit: BBC)

"There's a wholesomeness to the early web, an earnestness that's hard to find online these days," Milligan says. "Today we live on the internet. It's where our social lives are, where our commerce is, where we interact with our governments, where we decide what university we're going to. As a result, archived websites are the historical record of the last 25 years. They are the primary sources of today."

The chronicles of ancient websites have a deep and important history to unveil – but of course, there's also the pull of nostalgia.

Growing up, the slowness of the web was incredibly frustrating. All that buffering and loading ate into my one allotted hour of internet time – though it did make webpages somewhat more thrilling when it finally loaded.

To my delight, I discovered a website that recreates that experience. OldWeb.Today recreates the sluggish interfaces of outdated web browsers, from Internet Explorer 6 to prehistoric options such as MacLynx 2 and Navigator 3. If you want to go all out, you can even try "Old Google", which replicates former designs of the search engine dating from between 1998 and 2013.

But Old Google can't link you directly to the past; you have to find the old websites yourself. One method is to trawl through your own memories.

One day in school, while my teacher's back was turned, I logged on to their desktop computer and loaded up a Buffy the Vampire Slayer-themed chat room I had discovered during one of my illicit night-time excursions online. It was my first experience of instant messaging. My friends and I watched wide-eyed as strangers chimed in from other continents.

Archived websites are the historical record of the last 25 years. They are the primary sources of today – Ian Milligan

Sadly, but unsurprisingly, the Buffy site is no more. Enter the Internet Archive, a non-profit organisation dedicated to preserving the web. Perhaps it's no coincidence, as Milligan points out, that the Archive was founded in 1996, just as the internet's popularity exploded.

"In many cases, archives of the web, like those available from the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine, offer the only access to those otherwise-lost records," says Mark Graham, director of the Wayback Machine. "News stories, obituaries, poems, fan-fiction, travel reports, family histories and other pages that have special and unique meaning to people all over the world."

The Internet Archive has scraped more than 946 billion webpages, sometimes saving different versions of the same page multiple times a day. You can paste URLs in its search engine to find copies of decades-old sites.

I looked up "Buffy the Vampire Slayer" and there was the login screen, frozen in time since October 2003. I then tried Bebo, the long-gone social media platform I used in my pre-teens, and found 34,000 captures taken since 2000. My profile may be gone, but countless others have been saved, tiny windows into the lives of anonymous strangers from the past.

It reminded me of another site I spent hours bouncing around: eBaum's World, famous for viral videos, games, crude humour and stolen content – a repository for memes before they even had a name. The archived copies of eBaum's World perfectly encapsulate my early 2000s online experiences: a chaotic mish-mish of disparate interests. I found a page I remembered dedicated to celebrity soundboards. You could play audio clips through the phone and trick friends into thinking Jim Carrey was calling. There it was, saved for posterity.

One of Milligan's favourite research subjects is GeoCities, one of the first platforms that made it easy for anyone to host their own page online. GeoCities shut down in 2009, but much is preserved in the Internet Archive. Browsing its pages is like a trip back in time, a vision of an era when the internet seemed as private as it was public. "People felt that not everything they would say would be tracked back to them," Milligan says. "There's a refreshing candour to it, a sense that people are really engaging without self-censoring themselves."

GeoCities is perhaps best known for its graphic design, full of text in written in the font Comic Sans and the generous use of gifs. In fact, there's an entire search engine dedicated to it called GifCities. Type in a word or phrase, and you'll uncover mountains of animated digital folk art on the subject.

The Internet Archive isn't the web's only digital repository. In 2005, for example, Brügger helped launch the Danish Web Archive, committed to recording the nation's one million web pages. "It's really important that we preserve this cultural heritage, because it's an important part of our life," Brügger says.

Then there are the online artefacts that haven't gone offline. I was four years old in 1996 when a website promoting Space Jam, a live-action movie where Michael Jordan plays basketball with the Looney Tunes, was created. It's still intact in an archived form – a living relic from ancient times. The site is resplendent with an overbearing, repeating background pattern (a staple of early web design) and pages with barely enough information to justify their existence, at least by today's standards.

Getty Images

Getty Images

At a moment when so many complain the internet has lost its best qualities, revisiting the history of web's early days may offer another path forward (Credit: Getty Images)

I dug up another old website dedicated to the study of sporks, a perfect example of early internet humour seemingly untouched since – you guessed it – 1996. It felt wonderfully handmade: white and yellow text sitting on a plain black-background, with simple animations decorating the page. It captures a time when nothing was too niche or inane to warrant its own site.

An archive can feel more like visiting a museum than actively surfing the net, however, but that experience isn't totally lost either.

In the early 2010s, I let strangers send me to unexpected places on the web using StumbleUpon, a site that would take you to random webpages added by other users, full of obscure blogs or quirky homepages. StumbleUpon shut down in 2018, but the concept has been reborn, this time with a nostalgic twist.

A new tool called Wiby has a similar randomising button, but its library consists entirely of the handmade, idiosyncratic sites of the early web.

In a world of polished, algorithmically optimised content, the old internet is a testament to individuality and experimentation. People didn't necessarily care about appealing to big online followings or going viral. They made things for the sake of it. Because they loved whatever it was they were into. Now, as some worry that AI is ushering in an increasingly impersonal online experience, where human output is filtered and regurgitated via chatbots, the early internet reminds us that personality and human creativity was once far more prized.

It's hard to argue that today's internet isn't more useful, or at least more functional. But the internet used to feel like wandering through a college dorm, knocking on doors and seeing how each person had decorated their room to their individual tastes. You never knew what to expect, who you'd meet, or where you'd end up. It wasn't necessarily "better", but it was weirder, freer and far more personal. As the web enters its next chapter, perhaps those memories can steer us towards a more human online world.

.png)