The U.S. Navy will permanently cut its stream of data from three weather satellites essential to hurricane forecasters this Thursday, with the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season just weeks away.

As I first reported on June 26th, the U.S. Department of Defense initially gave a five-day notice that the critical satellite data – regularly used by forecasters to assess and predict the location and intensity of hurricanes – would be shut off at the end of June. After swift pushback from other government agencies, including from NASA’s Earth Science Division Director, for what amounted to a no-notice announcement, the Navy postponed the decommission date until the end of July.

Navy officials say they are restricting data access to these three juggernaut weather satellites – some in operation since 2005 – to mitigate a significant cybersecurity risk to the their High-Performance Computing environment. The moratorium notice issued June 30th, however, did not explain how the urgent IT security issue would be resolved through July as critical data continued to flow to NOAA and other end users like the National Hurricane Center.

The loss of data from the Special Sensor Microwave Imager/Sounder (SSMIS) instrument aboard each of the three defense satellites is significant and devastating to U.S. hurricane forecasters and to tropical cyclone forecast agencies around the globe.

The Navy’s Office of Information confirmed the July 31st decommission date with me last Wednesday in the following statement:

“We can confirm that the Navy’s Fleet Numerical Meteorology and Oceanography Center will no longer contribute to processing and disseminating Defense Meteorological Satellite Program data on July 31, 2025, in accordance with Department of Defense policy. DMSP is a joint program owned by the U.S. Space Force and scheduled for discontinuation in September 2026. The Navy is discontinuing contributions to DMSP given the program no longer meets our information technology modernization requirements.”

When I asked officials to elaborate on what’s changed about their IT modernization requirements that would suddenly prevent data dissemination, the Navy’s spokesperson said they had nothing further to provide on the matter.

As I’ve described in previous posts, there are no viable substitutes to this suite of weather satellites. In a statement to me last month addressing concerns about the premature termination of data from the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP), NOAA drew comparisons to other satellites and models in their portfolio that don’t offer the same high-power capabilities for hurricane forecasting. For instance, the statement cited the Advanced Technology Microwave Sounder (ATMS), currently aboard three surviving NOAA satellites as providing “the richest, most accurate satellite weather observations available.”

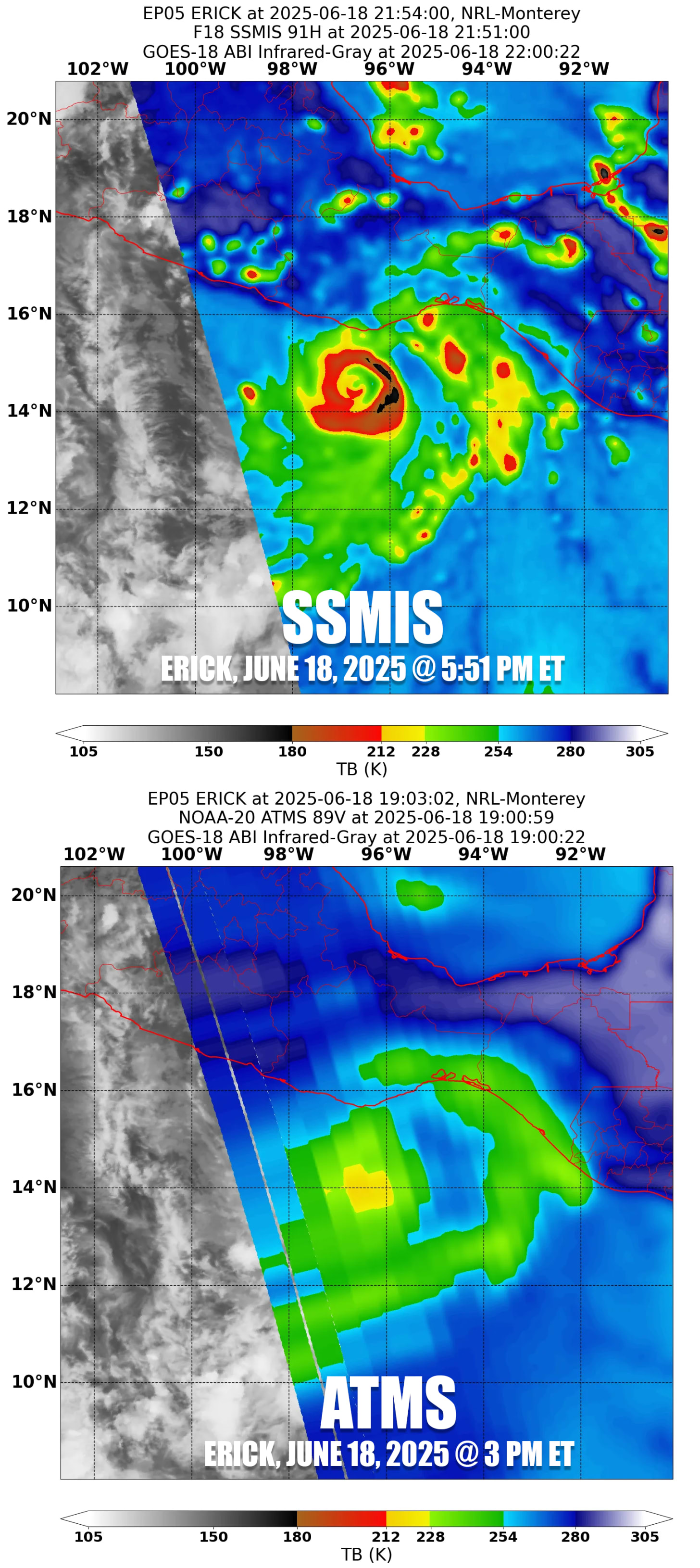

One recent example from Hurricane Erick back in June – which blew through forecast expectations, rapidly strengthening from a tropical storm to a Category 4 hurricane on approach to southwestern Mexico – illustrates plainly why NOAA’s claim doesn’t cut the mustard.

The ATMS instrument, unlike the SSMIS instrument aboard the DMSP satellites being terminated, is a cross-track scanner rather than a conical scanner, an important distinction that NOAA’s top-notch scientists know well. It’s been long documented for hurricane applications that conical scanning instruments provide superior performance to cross-track scanners, which suffer from degraded data for “sideswipe” scans, more common than not in hurricane monitoring.

The degraded data typically render ATMS scans useless to human forecasters and computer models requiring finer, inner-core details. Take rapidly strengthening Hurricane Iona today in the Central Pacific. Using only conventional infrared satellite or ATMS data would’ve completely missed important structural features that alerted forecasters to the first hurricane of the 2025 Central Pacific hurricane season. Thankfully, conical microwave scanners like the SSMIS quickly detected it.

Unlike conventional geostationary satellites that take nearly constant pictures of the same large region of Earth, these special low-earth orbiting satellites take only occasional snapshots in narrow swaths, so forecasters are lucky to get one or two useful snapshots a day across a hurricane with one satellite. We hope these snapshots arrive at critical points when we need them – as with Iona – so we don’t miss major structural changes that can portend episodes of rapid intensification or other sudden shifts in the forecast. The microwave sensors, unlike traditional satellites, peer beneath the clouds, giving a three-dimensional MRI-like glance inside hurricanes, a sort of night-vision goggles for hurricane forecasters.

Currently, only 7 satellites offer microwave imagers used by hurricane forecasters – one from Japan’s national air and space agency satellite (AMSR2), two from NOAA satellites (the previously mentioned ATMS), one from a combined NASA/Japan satellite (GMI), and three from the U.S. Department of Defense satellites (SSMIS). Each is important to maintaining adequate coverage and neutralizing blind spots to “sunrise surprise” hurricanes (the realization at first light that a hurricane is much stronger than what traditional overnight satellites can observe), a forecaster’s worst nightmare. With the elimination of 3 of these 7 satellites, our hurricane blind spot warning system is essentially cut in half.

The Department of Defense contends the three weather satellites are nearing their end of life, and it anticipates data suspension would come regardless toward the end of next hurricane season (September of 2026). That said, the satellites are already 15 years past their 5-year design life, and we’ve seen satellites far outpace end-of-life reliability estimates. Having two or three more hurricane seasons with these microwave satellites, as forecasters expected, would mitigate an abrupt loss and give scientists sufficient runway to test new data streams and adjust their models and algorithms to try to cushion the blow.

Instead, U.S. scientists, including forecasters at the National Hurricane Center, have been scrambling to plug the gaping holes these satellites will leave after their data stream is turned off Thursday.

Just two weeks ago, satellite experts at NOAA’s Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies or CIMSS (currently slated for elimination in NOAA’s 2026 budget) published new research in a journal of the American Meteorological Society exploring the feasibility of using a previously unexplored water vapor channel (183 GHz) aboard smaller microwave satellites to augment their state-of-the-art AI-powered hurricane intensity algorithms and forecast tools which rely heavily on the soon-defunct SSMIS data.

A new wave of cheaper, so-called smallsats or cubesats (the size of a loaf of bread compared to the usual bus-sized satellite, each costing about 100 times less than a typical low-earth orbiting satellite) is on the horizon, and with upcoming launches, scientists are testing whether they might make up for the deficit left behind by the three powerful defense satellites. Two NASA-operated TROPICS smallsats are set to decay in orbit at the end of this hurricane season, but more than 10 cubesats from Tomorrow.io – a Boston-based weathertech startup – are scheduled to be in orbit by the end of the year.

Because the smallsats are so much smaller and cheaper than traditional low-earth satellites, scientists can send more into space, thereby increasing coverage, with the goal of reducing the latency of snapshots and protecting our hurricane blind spots. But these next-gen smaller satellites don’t have the horsepower of their older and larger siblings and lack critical microwave channels or high-res channels to aid forecasters. So right now, neural network algorithms that estimate hurricane intensity and predict future hurricane intensity can’t use them.

Researchers at CIMSS, however, discovered an unexplored 183-GHz channel common among smallsats might be useful for their models and algorithms built for and routinely used by hurricane forecasters. What’s more, the 183-GHz spectral band is notably sharper on these smallsats than channels scientists have traditionally relied on from bigger polar orbiters, upping the potential utility of the smallsats and perhaps offering a viable replacement for the mighty defense satellites.

The researchers tested this novel 183-GHz channel first in the legacy heavier class of satellites, like the defense weather satellites, and found it gives similar high-quality results as traditional 37- and 89-GHz microwave channels. But the promising results didn’t carry over to the new, lighter class of smallsats and the performance using the 183-GHz channel wasn’t any better statistically than a baseline model absent all microwave satellite data. In other words, for all the promise of the new smallsats, they’re still no replacement for their older, more expensive, and much larger siblings.

But the Defense Department is not entirely out of the big satellite game. In April 2024, they successfully launched a replacement microwave weather satellite aboard a Space X Falcon 9 rocket from California. Although the Weather System Follow-on Microwave satellite or WSF-M reached operational acceptance earlier this year, as of this writing, its data stream still isn’t available to forecasters and no timeline has been announced. Even when the WSF-M comes online, it will have only 6 frequencies compared to the 21 on each of the three defense weather satellites going dark this week. Additionally, the one satellite will pale in coverage to the three we’ve had, and the WSF-M doesn’t include an onboard sounder like the SSMIS, meaning it will have little to no impact on weather forecast models.

Despite their best efforts, scientists haven’t yet found an alternative to reduce the major degradation to hurricane forecast capabilities once the Navy ends transmission of data from the three Defense weather satellites this week.

According to experts familiar with the Navy’s computing architecture, the IT security concerns are valid, though Defense officials chose not to fund or prioritize efforts to patch the issue.

DMSP weather satellites transmit data to U.S. Space Force MARK IVB meteorological data stations around the world. Only nine of these receiving sites are in existence worldwide and receive the data – including the critical SSMIS data – when the DMSP satellites are within their line of sight.

The weather satellites also store data onboard and relay this stored data – including all real-time global SSMIS data – to sites with domestic communications satellite (DOMSAT) antenna, a relic of the 1970s and 1980s. Today only one operable DOMSAT antenna is left and it’s owned and operated by the Navy’s Fleet Numerical Meteorology and Oceanography Center (FNMOC). The software used by the antenna is some 40 years old and unsurprisingly doesn’t meet present-day information assurance compliance.

It's unclear what level of effort is required to update the software, but the decision to cut the data rather than patching the security risk doesn’t appear to weigh the risk the premature outage poses to U.S. national security and critical DOD facilities around the world (full disclosure: I served in a tropical cyclone advisory capacity to DOD in the past, so these are matters with which I’m familiar).

The three DMSP weather satellites account for about 2 in 3 daily conical microwave sensor observations. These are the most useful and most accurate platforms available to observe and forecast the intensity and locations of hurricanes in the absence of hurricane hunters.

As I’ve mentioned in previous posts, the NOAA hurricane hunters are missing about half their critical support scientists due to DOGE-directed layoffs and buyouts. Data we typically expect from hurricane hunters (only available for about 1 in 3 forecasts) will suffer as a result, so we'll likely lean increasingly on our best available satellite data, which will drop dramatically later this week.

Forecasters and other experts I’ve spoken with resoundingly described the upcoming hit as “significant,” and anticipate delayed forecasts of rapid intensification because of them, throwing forecasts for the remainder of this hurricane season and beyond off balance.

.png)