Whilst the world and its money is focused on the possibilities offered by AI, it’s easy to miss interesting events elsewhere. One such development happened this week in the Netherlands.

‘Takes control’ is shorthand for a number of actions including suspending CEO Zhang Xuezheng from his role and his board seat. The rationale for these actions?

It’s not the first time that Nexperia has been at the centre of concerns about Chinese ownership. In 2021 Nexperia bought Newport Wafer Fab in Wales in the UK. This Fab was the original UK base of parallel computing pioneer Inmos, whose groundbreaking Transputer we’ve discussed in previous posts.

Newport Wafer Fabs sale to Nexperia led to challenges from lawmakers in the U.S.

In a letter sent to President Joe Biden on April 19, 2022, the Republican-led, special congressional task force known as the China Task Force (CTF) expressed concerns over the takeover of Newport Wafer Fab (NWF) … the letter raised questions regarding Nexperia’s ownership by Wingtech Technology (Wingtech) of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), claiming that Nexperia is “in effect a PRC state-owned enterprise.” Research cited in CTF’s letter suggests that the Chinese government owns at least 30 percent of Wingtech Technology’s shares.

The British Government would ultimately block the deal:

The British government has blocked the takeover of the UK’s largest producer of semiconductors by a Chinese-owned manufacturer, citing “a risk to national security”.

The business department’s decision on Wednesday comes more than a year after semiconductor company Nexperia first announced that it had taken control of Newport Wafer Fab in south Wales in July 2021, in a £63m deal.

A sale price of £63m seems like ‘small beer’ compared to the trillions being invested in AI chips, so what was all the fuss about?

who writes the terrific

Substack, in addition to his day job on the UK’s Sky TV, explains that the Newport Fab makes ‘power semiconductors’ and does it well:

So, a mark of a fab’s success is its average yield, and it turns out on this front Newport is very good indeed.

With a yield percentage in the very high 90s, among power silicon chipmakers it’s one of the best in the world.

The other thing that’s under-appreciated is how valuable this site is.

If you wanted to tear down this building and reconstruct it, with all the machinery, it would probably set you back about a billion pounds.

It is, in other words, one of the most expensive factories in the UK.

Now, it’s certainly true that what they do here is categorised as the low-value, high-yield end of the semiconductor sector.

In a typical car these days you might have hundreds of these power chips for everything from brake lights to wing mirrors, but only a few of the logic chips - those “brains” - to work the navigation and media console.

If you want a sign of how much these semiconductors matter, recall that a sudden shortage of them - both the “brain” ones but also the power ones - has caused a major downturn in car manufacturing, not to mention other sectors.

Without even these small power chips, you can’t make, well, pretty much anything.

In short, the Newport Fab’s products are relatively low tech but also essential.

So what about the rest of Nexperia? In the rest of the post we’ll look at Nexperia’s history and explore the rationale for the Dutch government’s actions.

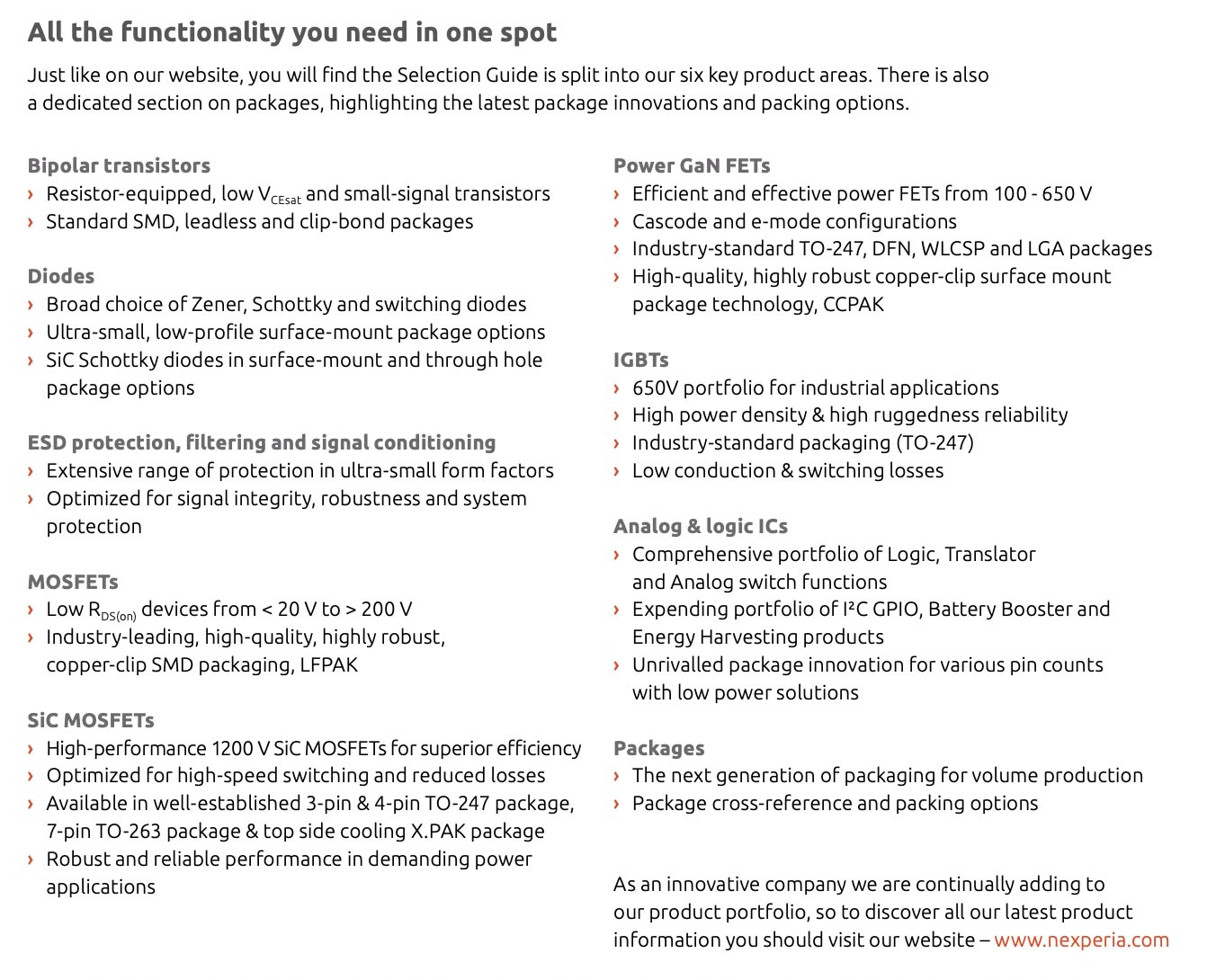

Nexperia may have failed to acquire the UK’s Newport Wafer Fab but what does the rest of the business make and where does it make it. For the ‘what’ we can turn to the company’s product catalogue (or Selection Guide as the firm calls it) which lists thousands of products in its 240 pages.

Bipolar transistors, diodes, MOSFETs, Analog switches and so on. Definitely not leading edge processes.

And here is just one page of (individual) transistors from the catalogue.

I didn’t manage to get hold of a price list but I suspect that most are relatively inexpensive. Again cheap does not equate to unimportant though, especially in key industrial sectors such as automotive where these products are vital.

Answering this question takes us into the deep history of electronics in Europe.

Although it’s a Dutch company, Nexperia only has 400 employees in the Netherlands. Manufacturing in the firm’s “Fabs’ takes place at two locations in the UK and Germany with further assembly operations in China, Malaysia and the Philippines.

Readers in the UK may be familiar with the ‘Mullard’ brand. Mullard was founded by Captain Stanley R. Mullard all the way back in 1920 as a vacuum tube or ‘valve’ manufacturer.

Mullard was acquired by Dutch conglomerate Philips, but continued to manufacture its components in the UK, including at a site near Manchester that continues to make components as part of Nexperia today.

Nexperia’s other production plant in Hamburg in Germany dates back as far as 1924 and sold vacuum tubes under the ‘Valvo’ brand. Philips also acquired the plant soon after its founding.

Both sites transitioned to making transistors in the 1950s. Philips had experimented with solid state electronics as far back as the 1930s:

Philips had formed a dedicated solid state physics group within NatLab in the 1930s. It worked on the known semiconductors of the time: copper oxide and selenium and developed a selenium diode that went into production at the Electron Tubes product division. But it had no success with its research in solid state amplifiers and field effect devices. However, this group provided an important platform and the focus as Philips positioned itself for the semiconductor era.

Bell Laboratories announced its point-contact transistor in June 1948: “An amazingly simple device, capable of performing efficiently nearly all the functions of an ordinary vacuum tube, was demonstrated for the first time yesterday at Bell Telephone Laboratories where it was invented.” …

The importance of this breakthrough was not lost on Philips. For example, after reading the article, Verweij said to Hazeu, who was the commercial director of the Electron Tubes product division: “The content of this article will shake your department to its foundations!” Source

One fun example of these Philips’s companies activities: In the 1980s, Philips owned Mullard made the chip that generated the text mode display in the BBC Micro, explained here by Arm designer Steve Furber. A niche but important chip - it would probably also have been used in millions of televisions - in its day.

Although the Philips brand today may be more associated with light bulbs and medical equipment (and with CD players for those of a certain age) it was once a sprawling conglomerate that seemed to do just about everything associated with electronics.

Perpetually in search of focus, as a result it’s been a perpetual source of ‘spin-offs’ too. The most famous and successful of course is of ASML in 1984 a firm whose value of more than $300 billion dwarfs that of its one-time parent.

In turn Philips semiconductor manufacturing businesses were spun off as NXP in 2006. NXP then spun-off some of its businesses as Nexperia in 2017 selling to Chinese Investors:

The Nexperia spinoff was first announced last year when NXP sold the business for $2.75 billion to Chinese investors including Wise Road Capital and JAC Capital, also known as Beijing Jianguang Asset Management.

Wingtech then acquired a controlling stake in the company in 2019. Wingtech started life as an contract manufacturer including making mobile phones. In an interesting twist it seems to have been the manufacturer of the Trump Mobile ‘T1 phone’ although as we’ll see this business has apparently now been sold:

That smartphone is made by Wingtech, owned by the Chinese-owned manufacturer Luxshare. The T-Mobile version is believed to be built in Kiaxing, Wuxi, or Kunming, in China.

The T1 appears to be a reskinned version of the REVVL 7 Pro 5G, in a new enclosure and with slightly moved around cameras. This smartphone normally costs $250 at full retail, and even goes down to $169 on sale like it is on Amazon right now.

Back to Nexperia. To give some indication of scale, the firm had turnover of $2 billion in 2024: tiny really in the context of global semiconductor businesses.

So why did the government of the Netherlands intervene at Nexperia?

The Dutch news site nrc has some very specific allegations (the original in Dutch with translation courtesy of Arc) based on the Dutch appeal court ruling:

The Dutch government took drastic action against Nexperia because its Chinese CEO, Wing, wanted to use Nexperia’s money to finance another company, the chip manufacturer WingSkySemi. He appointed front men and attempted to fire European executives. This reckless act led to a heated dispute, according to a ruling by the Enterprise Chamber published Tuesday .

Nexperia is owned by the Chinese holding company Wingtech, led by Zhang Xuezheng (’Wing’). The 50-year-old entrepreneur is also the CEO of Nexperia. He also owns other tech companies in China, including a factory that produces wafers – round disks filled with chips.

Wing commissioned the construction of WingSkySemi in Shanghai, a modern chip factory where Nexperia also had some of its chips manufactured. However, WingSkySemi ran into financial difficulties this year due to a lack of customers. To solve these problems, Wing wanted to use Nexperia’s financial resources – even though WingSkySemi isn’t part of the Wingtech group. But Wing wasn’t interested: he wanted to force Nexperia to place large orders with his chip factory, even though the company didn’t need them at all. Nexperia needed $70 to $80 million worth of wafers by 2025 , but orders worth $200 million had already been placed. A waste of money to keep WinSkySemi afloat.

Expanding on the latter point, a key section from the Court’s ruling says (WSS is WingSkySemi, emphasis is mine):

Nexperia has extensively substantiated that very large orders were placed with WSS in 2025, orders of a size that Nexperia does not need and that, according to Nexperia employees , were even placed for scrap (for destruction). According to an internal estimate dated May 8, 2025, the Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor business unit would need a total of 98,400 wafers in 25Q2, 25Q3, and 25Q4 . However, [director/CEO] insisted that Nexperia order 215,000 wafers from WSS for this business unit . While the Logic business unit expected to need 400 wafers per month, [director/CEO] wanted 5,000 wafers per month from WSS. [Director/CEO]’s desired orders from WSS for 2025 thus amounted to US$200 million, while the business ‘s actual needs would result in orders of US$70-80 million. According to internal reports, this would mean that the wafers to be supplied by WSS will not be processed, but will be held in stock until they are obsolete before they can be used, so that Nexperia would effectively place the orders for scrap.

There were also concerns about Nexperia’s response to being potentially subject to US trade sanctions as a result of its ownership (the 50% rule below):

It was clear to all involved that the 50% rule could have a significant negative impact on Nexperia and its business …

Nevertheless, no steps were taken to adjust the governance in the interests of Nexperia and its company. This was not even the case when it became clear in June 2025 that there was a significant chance that the 50% rule would be implemented, which would also directly affect Nexperia by trade restrictions from the United States. From that moment on, it was up to [director/CEO] to take measures to minimize the risk of Nexperia being affected by the 50% rule …

From September 2025 onward, [director/CEO]’s actions even pointed in the opposite direction.

In these circumstances it’s probably not surprising that the Dutch government took action.

I’ve attached a translation to English of the full court ruling. It’s an interesting read with not too much legal language.

What will happen now? It’s difficult to tell. Nexperia now seems to make up the large majority of Wingtech’s business, the firm having sold its original contract smartphone assembly business to Luxshare earlier this year. It’s now seems to be a shell company wrapped around a Dutch firm over which it has no control. Investors in Wingtech in Shanghai understandably marked down the share price on the news.

I find it hard to believe that the company will regain control of Nexperia after the events of this week. Sale of the firm to a non-Chinese owner seems the likeliest outcome. This certainly isn’t the end of the story though as headlines today make clear.

Before leaving Nexperia, it’s worth noting that Qualcomm’s takeover of Nexperia’s former parent NXP was blocked by Chinese regulators in 2018:

BEIJING/SAN FRANCISCO (Reuters) - Qualcomm Inc walked away from a $44 billion deal to buy NXP Semiconductors after failing to secure Chinese regulatory approval, becoming a high profile victim of a bitter Sino-U.S. trade spat.

The world’s biggest smartphone-chip maker and Netherlands-based NXP confirmed in separate statements on Thursday that the deal, which would have been the biggest semiconductor takeover globally, had been terminated.

…

“We obviously got caught up in something that was above us,” Qualcomm Chief Executive Steve Mollenkopf said in an interview after the announcement on Wednesday.

The key lesson from this episode: it’s not just leading edge electronics that are geopolitically sensitive. There are other key components, some with legacies dating back many decades, that are vital parts of modern supply chains.

Even for relatively ‘low tech’ businesses, regulators and geopolitics can have a long reach.

.png)