Pablo Picasso, co-inventor of Cubism and a titan of the 20th century, excelled at many things: painting, sculpting, ceramics, printmaking, and even theatrical design. And those aren’t even all the art forms he practiced. He was also, after a fashion, a writer.

That’s right—the Spaniard took up poetry in his mid-50s. To some degree, this might not come as a surprise; he had had been moving in literary circles since he first moved to Paris in his early 20s. Counting among his closest friends the poets Guillaume Apollinaire, Paul Eluard, and Max Jacob, Picasso had been socializing with those at the heart of European Modernist poetry for three decades.

Picasso’s poetry period began in 1935, following an emotional crisis sparked by the beginning of his separation from his first wife, the Russian ballet dancer Olga Khokhlova, and the birth of his daughter Maya by his mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter, which saw him put down his paintbrush and pick up his pen.

By the end of 1935, Picasso’s friend André Breton, poet and founder of the Surrealist movement, was translating Picasso’s poems into French and publishing them in the magazine Cahiers d’art. Breton compared the experience of reading Picasso’s poems to “being in the presence of an intimate journal, both of the feelings and of the senses, such as has never been kept before.”

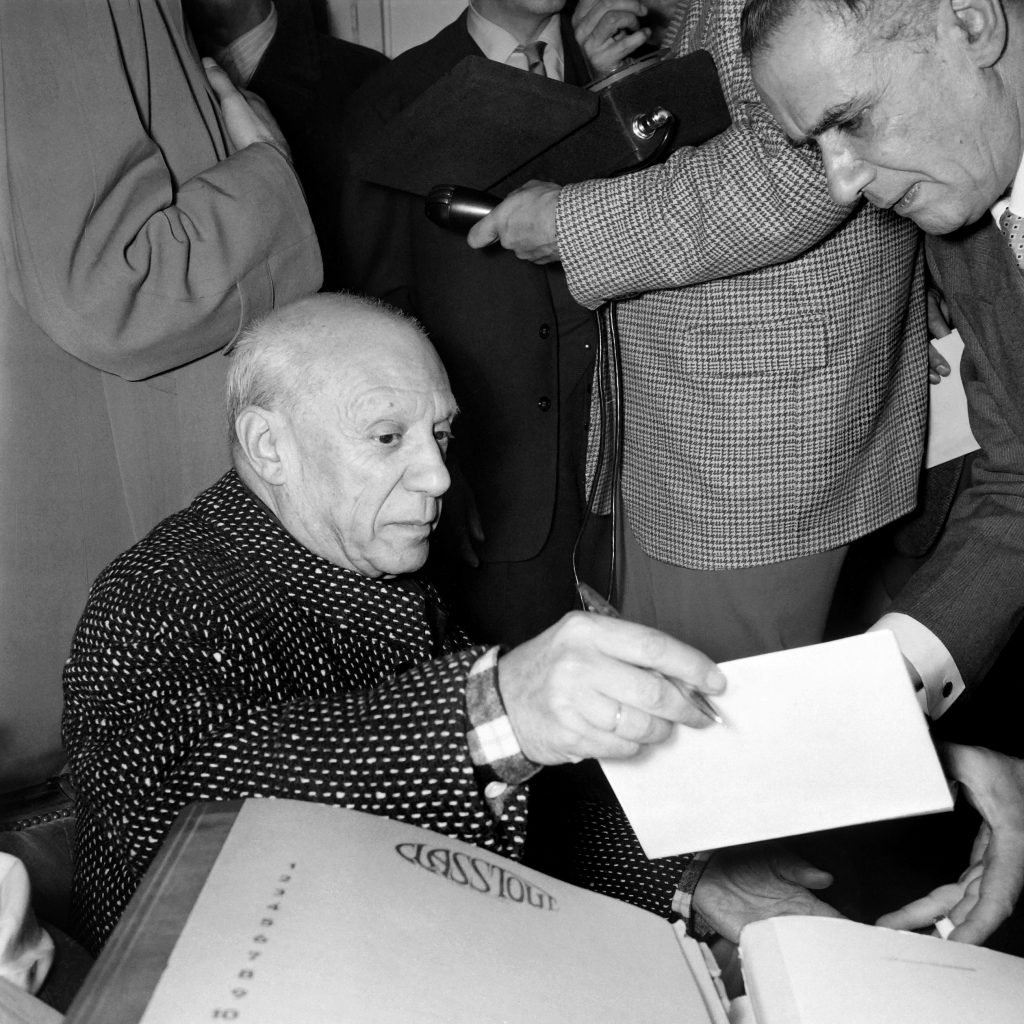

Pablo Picasso signs autographs on December 24, 1956 at the opening of an exhibition. Photo: Pierre Meunier/AFP.

Picasso’s poetry was, in several ways, like his paintings. Firstly, it featured strange metaphorical imagery, like in one excerpt describing a bizarre chain of consumption:

“the street be full of stars

and the prisoners eat doves

and the doves eat cheese

and the cheese eat words

and the words eat bridges

and the bridges eat looks

and the looks eat cups full of kisses in the orchata”

Picasso’s portrait of Dora Maar on view at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia, 2006. Photo: William West / AFP via Getty Images.

Secondly, like his visual art, his poems are often inspired by the women in his life. For example, Her Great Thighs, about his mistress and muse, the artist Dora Maar, begins with a lengthy inventory of body parts:

“Her great thighs

Her breasts

Her hips

Her buttocks

Her arms

Her calves

Her hands

Her eyes

Her cheeks

Her hair

Her nose

Her throat

Her tears”

And lastly, as he did with his Cubist visual artworks, he also sought to change the way the art form was fundamentally structured. Picasso eventually gave up on the use of punctuation altogether, describing it as a “cache-sexe [a G-string] which hides the private parts of literature.”

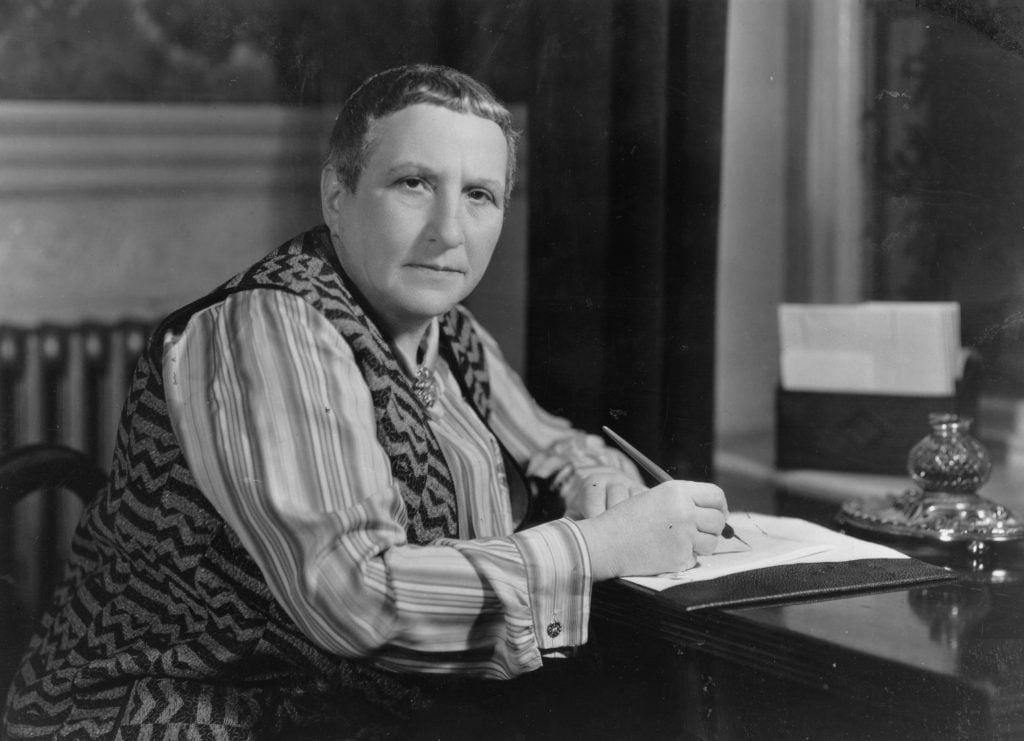

The artist’s efforts at poetry didn’t go down well with all of his critics. In her book Everybody’s Autobiography (1933), writer Gertrude Stein (Picasso’s first patron) recalled, in her distinctively unconventional style, the Spaniard begging her for feedback on the poems he had written while he had been “leading a poet’s life.”

Stein made a damning comparison to the artwork of another of Picasso’s friends, the poet Jean Cocteau: “You see I said continuing to Pablo you can’t stand looking at Jean Cocteau’s drawings, it does something to you, they are more offensive than drawings that are just bad drawings now that’s the way with your poetry it is more offensive than just bad poetry I do not know why but it just is.”

Gertrude Stein, 1936. Photo: Hulton Archive / Getty Images.

When the artist fought back against this critique, she wrote that she told him, while “catching him by the lapels of his coat and shaking him,” that “you are extraordinary within your limits but your limits are extraordinarily there.”

Stein even wrote her own poem about Picasso, If I Told Him, A Completed Portrait of Picasso (1923), in which the author abstractly associates the artist with Napoleon Bonaparte.

Years later, in 1949, Stein’s partner, the writer Alice B. Toklas, would neatly summarize Picasso’s poetry era, writing that “the trouble with Picasso was that he allowed himself to be flattered into believing he was a poet too.”

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history.

.png)