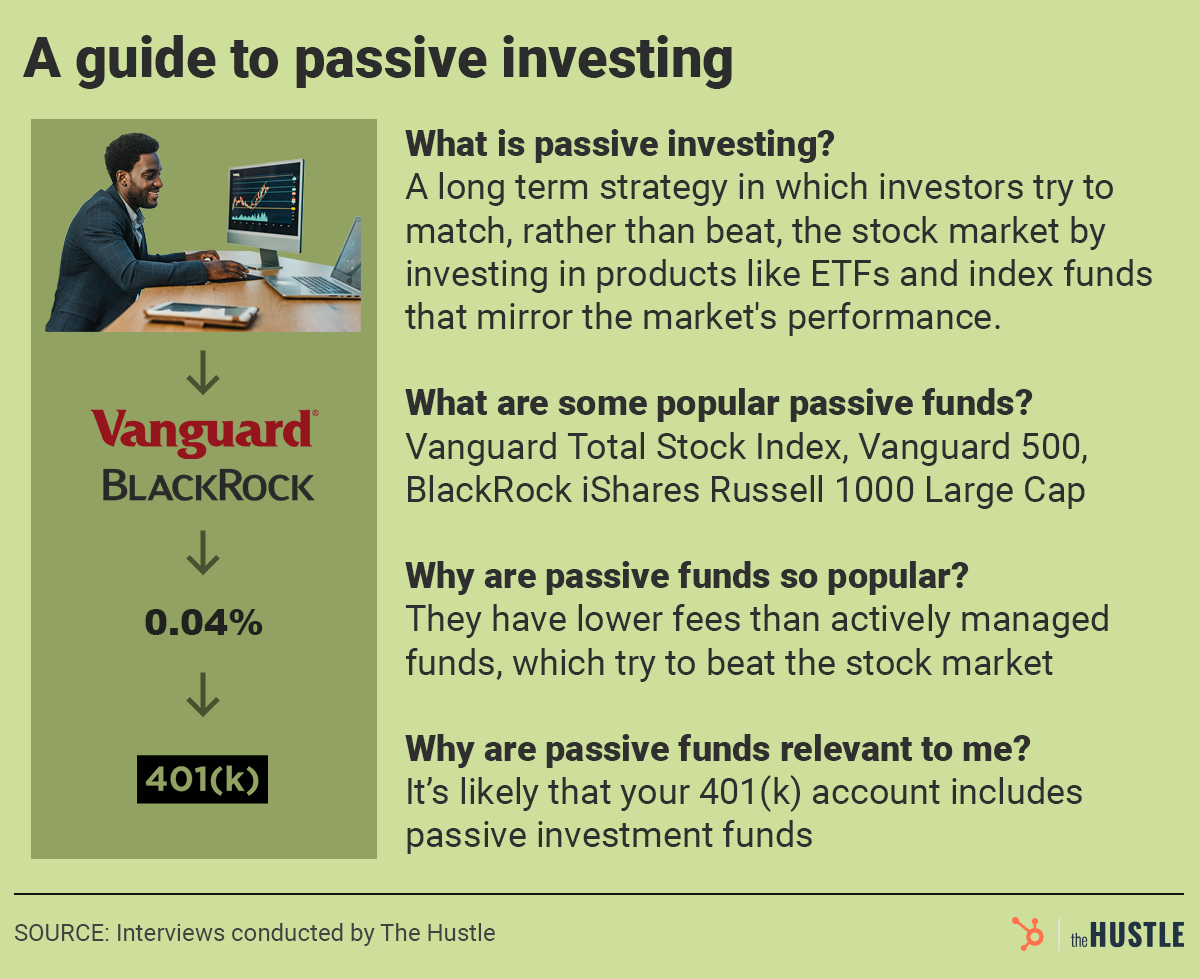

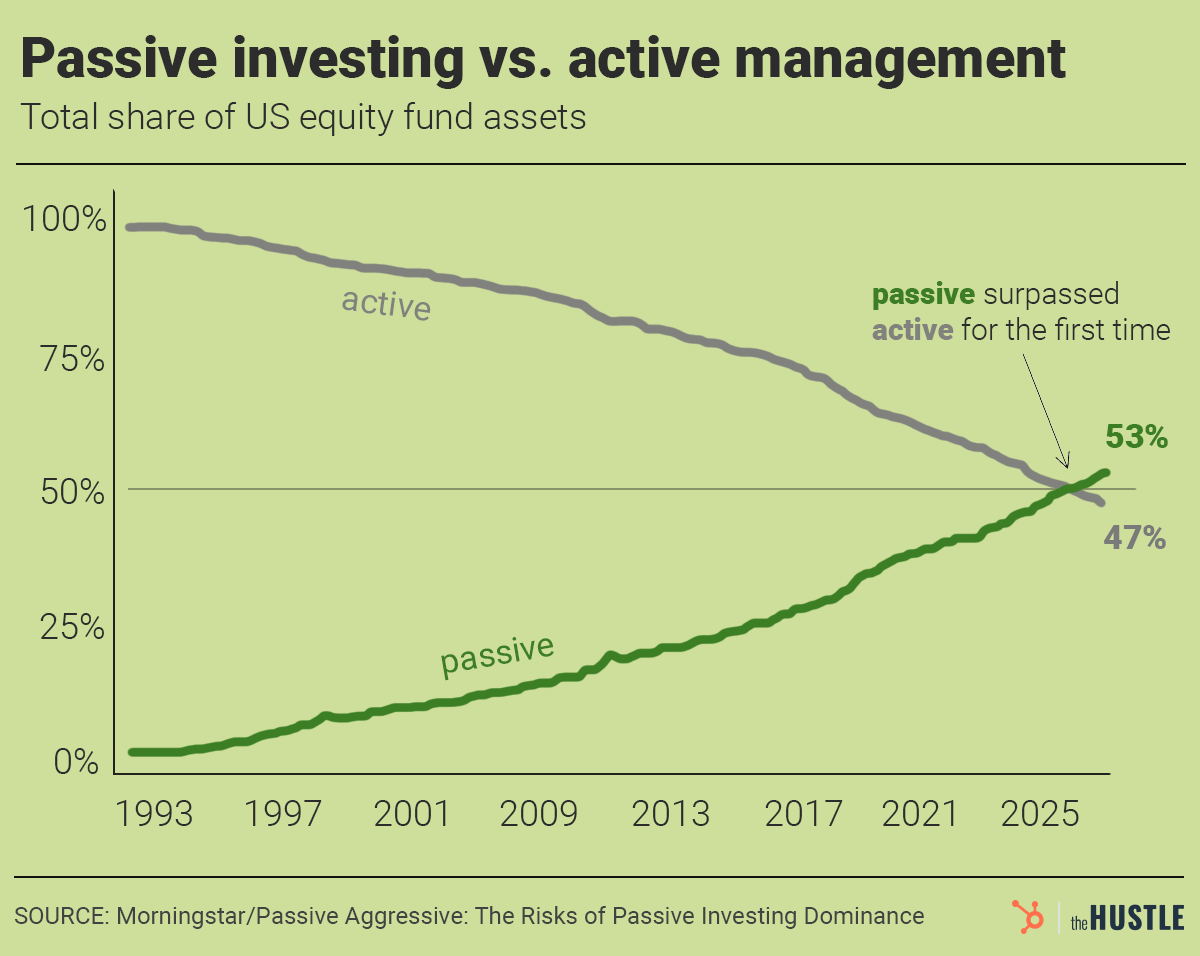

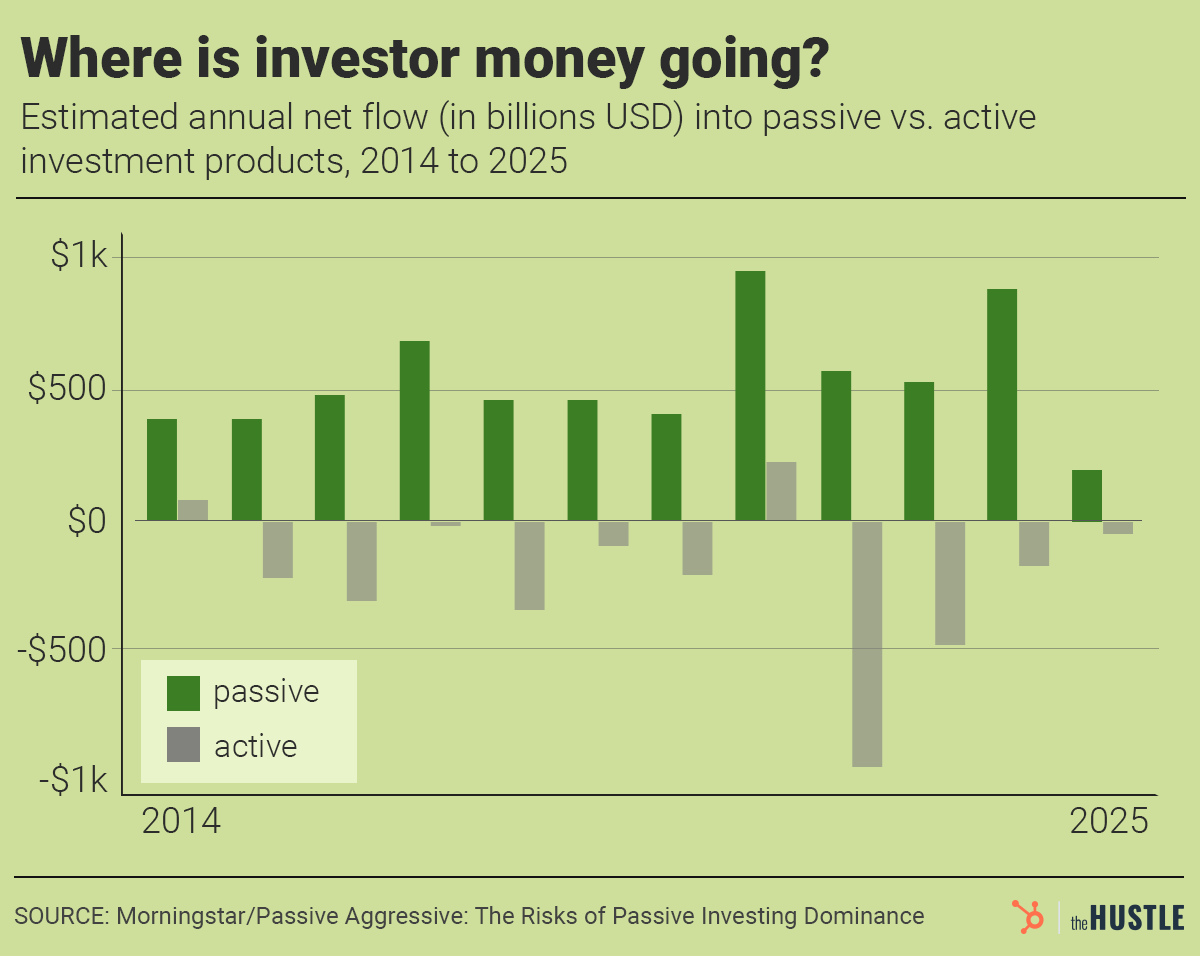

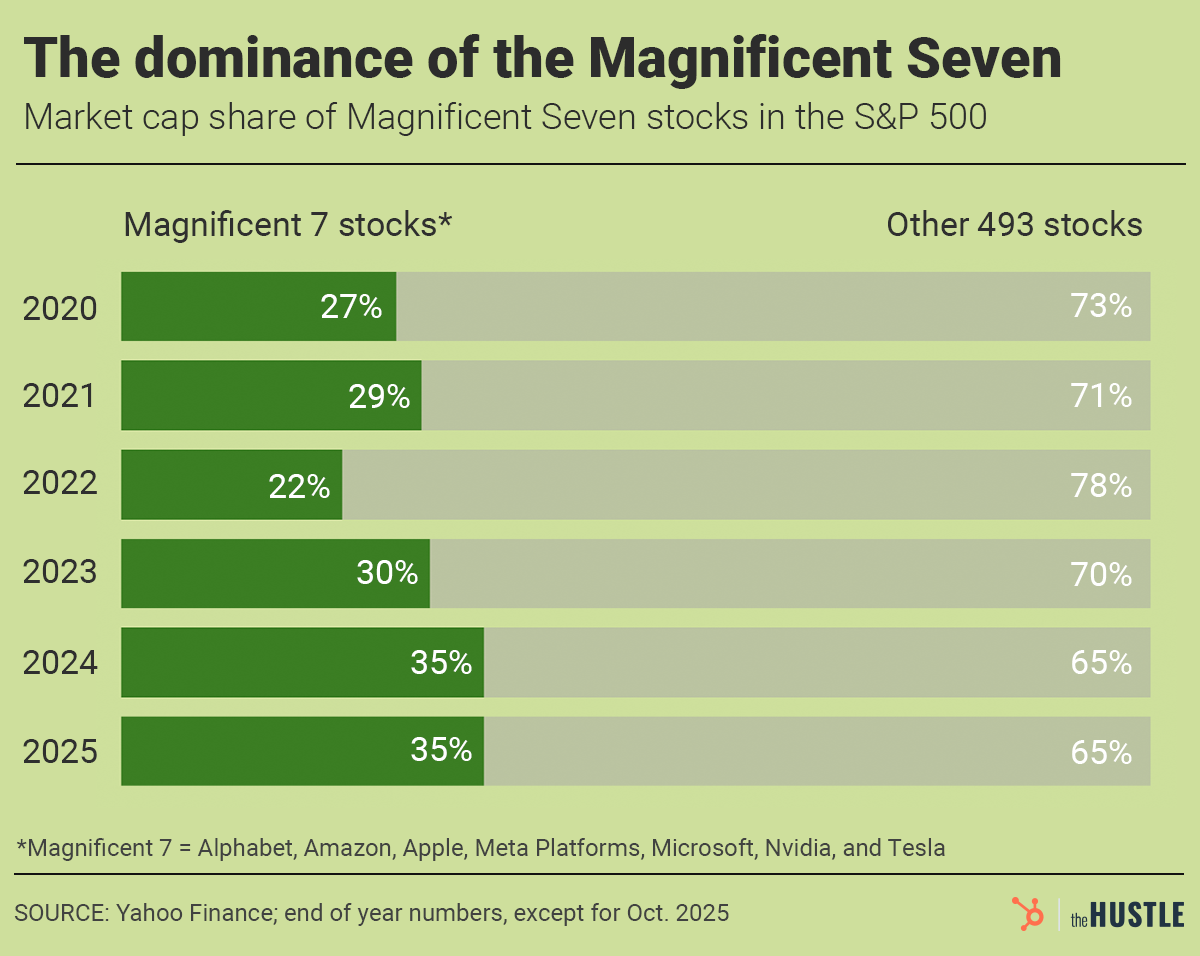

The growth of passive investing, through index funds found in the 401(k) accounts of average Americans, has propped up the stock market while also potentially setting it up for a nasty fall. The stock market just keeps going up. In late October, the S&P 500 reached a record high for the eighth time this year. That came after it reached 13 record highs in 2024 and set multiple records in the 2010s. Although stocks experienced a tough first week of November, they’ve generally risen this year despite: The Hustle Not everything is glum, of course. AI growth (powered by Nvidia), solid corporate earnings reports, trade deals, and interest rate cuts by the Fed have all provided reasons for optimism. But there’s also a scary possibility for why the stock market has done so well for so long: You might be propping it up. Yes, you. The person who doesn’t pay any attention to the stock market. The person who heard you should just put money in an index fund or ETF, or who just contributes 15% of your paycheck into a 401(k) fund that you know nothing about but is, in fact, a target date fund filled with products managed by Vanguard, BlackRock, or State Street. If that sounds like you, you are — like a huge number of Americans — engaged in something called passive investing. The Hustle As of last year, ~53% of all money invested in US equity funds was under passive investment, locked into index funds or similar investment vehicles commonly held in pensions or 401(k) accounts. That’s up from ~4% in 1993, enough to comprise nearly one-fifth of all money invested in the stock market. Some experts believe the total number of assets tied up in passive funds could be 2x higher because many active fund managers have started replicating passive fund strategies. Passive strategies are preferred by 71% of Americans, according to Gallup, and are almost universally recommended. Warren Buffett, one of the world’s great stock pickers, has even said index funds are the best choice for average Americans. As passive investing has grown, so has the overall market, which has continued a bull run that started back in October 2022 and has faced few setbacks since 2010. Several academics and notable investors have credited the rise of passive investing with helping stabilize and inflate the stock market. The only problem: The same passive characteristics fueling the boom could lead to a nastier fall. In 1975, banker John Bogle founded an investment product that would change the world. Bogle introduced the first index fund for everyday investors, a precursor to the Vanguard 500. At first, insiders critiqued the fund as “Bogle’s folly.” A copycat index fund didn’t arrive until nine years later. Eventually, though, passive funds took off. (And Bogle became a legend in the investing world; a “Bogleheads” subreddit has 750k members.) Their use accelerated among people who sought stability after the Great Financial Crisis of 2008. The Hustle The key difference between active and passive investing is: For example, the Vanguard 500 attempts to replicate the S&P 500, a weighted index of the largest 500 stocks by market cap, by selecting stocks based on their prominence within that index. As of late October, Meta ranked as the 5th largest stock, comprising 3.2% of the S&P 500. So Meta made up ~3% of the Vanguard 500. The passive investment fund sees the stock price, “and that’s it,” says Campbell Harvey, a Duke University finance professor who’s researched passive investing. “They don't care about the trend and earnings. They don't care if there's a new CEO. They don't care. It's just the price.” Passive funds are attractive because, with their investment fees typically running ~80% lower than active funds, they’re viewed as a cheaper way to own a diverse assortment of stocks. They’re also easier for people who want to invest money for a long period without thinking about it — a strategy that typically leads to greater returns than trying to time the market. Over the past 10+ years, passive funds have indeed proven to be a smarter investment. The vast majority of actively-managed funds (with their higher fees taken into account) have failed to outperform average index funds, according to Morningstar data. For the last decade, not coincidentally, hundreds of billions of dollars have flowed into passive investment funds every year while hundreds of billions have flowed out of active funds most years (with the withdrawn money often transferred into passive funds). The Hustle So, how has this type of investing warped the stock market? Passive investing leads to the potential overvaluation of stocks, especially large ones. Under passive management, money flows into big stocks like Meta simply because they’re bigger in relation to other stocks, regardless of the overall health or outlook of the company. That makes them even bigger and drives an even greater flow of money in a loop. “Higher returns attract more flows, and more flows push it even higher,” says Hao Jiang, a Michigan State University finance professor and co-author of the 2024 study “Passive Investing and the Rise of Mega-Firms.” That has led to the concentration of investment money among a small number of stocks, those first known as FAANG in the 2010s and now called the Magnificent Seven (Meta, Tesla, Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, Alphabet, Amazon). As of late October, the value of those seven stocks accounted for ~35% of the value of the S&P 500. The Hustle The overall effect has been a rising stock market, "asymmetrically driven” by the Magnificent Seven, Jiang said. Not only that, Jiang’s study found that the flow of money from active funds to passive funds had increased the overall value of the stock market, even though that money wasn’t new and had merely switched from one type of fund to another. In the past, active investment managers could negate overvalued stocks by selling or shorting them. They could elevate undervalued stocks by investing in them. But because the flow of money from passive investment funds has become so significant, it has outweighed the influence of active funds and discouraged active fund managers from betting against the power of passive funds. So, if the stock market is warped in a way that has driven stocks consistently upward, who cares? Isn’t that a good thing? For now, yes. However, as Jiang says, the “long-term tendency of capital markets is not to keep going up.” And, given the high concentration of the Magnificent Seven, a significant decline in their stock prices would have an outsized effect on an average American's passive fund portfolio. Perhaps most importantly, and counterintuitively, passive investing has created a lack of diversity in the stock market: This connective tissue increases the risk of what Harvey calls a “systemic event.” A mass withdrawal of funds — precipitated by, say, a down economy or if a critical mass of Boomer retirees exit their investments in the coming years — would cause much of the market to go down at the same time. John Bogle at the 2002 Money Summit. (Mark Peterson/Corbis via Getty Images) It would also damage stocks that might otherwise be healthy during a downturn simply because they’re tethered to so many other stocks through index funds. Nobody can predict if, or when, such a market correction may occur. Harvey says this with confidence, though: If passive management continues to grow at its current rate, he estimates that its share of overall funds will climb to ~80% a decade from now. He and others concerned by the glut of passive investing and concentration in the market have proposed hybrid alternatives that combine low fees with more selective stock picking. And if the early November market malaise continues, more money could flow into active funds. But, for now, passive investing remains the easy and popular choice for average investors. Among those who’d be worried by its increased dominance? Bogle, the guy who invented it. Months before he died in 2019, he wondered if his innovation had become “too successful for its own good.”

The rise of passive investing

What does this all mean for the market?

.png)