Most of us imagine the microcomputer revolution as small groups of nerdy kids working in garages and bedrooms to build technology that would change the world. It is less known that much of the early software for the micros was developed on powerful mainframes and minicomputers, often on Digital Equipment Corporation’s PDP-10, a 36-bit mainframe designed for timesharing.

Some important early microcomputer software products were developed or prototyped on the PDP-10:

Digital Research’s CP/M - the first commercial operating system for microcomputers.

Microsoft’s early products, including the Altair BASIC.

VisiCalc - the first spreadsheet application for personal computers.

In 1973, Dr. Gary Kildall worked full-time as an assistant professor at Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) at Monterey, California, and part-time as a consultant for Intel. He wrote simulators and cross-assemblers for Intel’s early microprocessors: the 4004, 8008, and 8080.

Kildall proposed developing a high‑level language for those microprocessors, called PL/M. Convincing Intel took some effort as even Intel’s cofounder and coinventor of the integrated circuit Bob Noyce did not see microprocessors as viable general-purpose CPUs at that time.

The plan was to first develop a cross-compiler for Intel’s microprocessors on a PDP-10 mainframe in FORTRAN and then use it to bootstrap a compiler that would run on the Intellec-8 development system. The cross-compiler was done successfully, but hosting the compiler on the Intellec-8 faced a serious problem: lack of reliable and fast storage.

Fortunately, a new storage device called floppy disk was getting cheaper, and Shugart Associates donated one to Kildall. He still wasn’t able to actually use it, as he lacked a disk controller, so he returned to the PDP-10 and used his cross-compiler and simulators to develop a small operating system for 8080-based machines which he called CP/M.

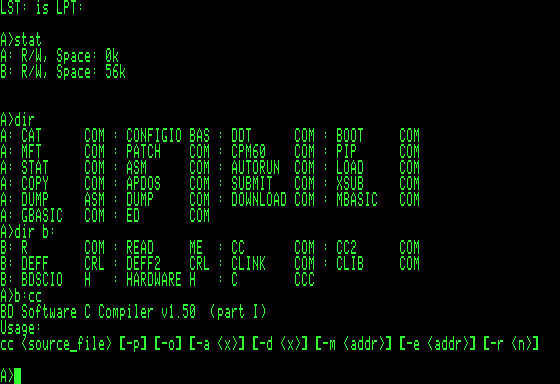

CP/M was minimalistic, as it was designed to run with very limited amount of memory, but it is clear that it was influenced by the PDP-10 operating system TOPS-10. It used three-letter file extensions, including standard ones like EXE and TXT. Some CP/M commands were directly ported from TOPS-10.

Gary Kildall was a visionary, innovator, and educator, but not a businessman. He wanted to sell CP/M to Intel for $20,000 and continue teaching at NPS. Intel declined the offer, but soon the first commercial microcomputers appeared and they needed an operating system. Gary’s wife Dorothy saw a business opportunity and the Kildalls formed a company - Digital Research Inc. (DRI).

CP/M became an industry standard for 8-bit business computers. Although IBM PC clones that ran Microsoft’s MS DOS operating system (itself a CP/M lookalike) took over by the mid-1980s, CP/M and its successors such as DR-DOS remained viable alternatives until the rise of Windows.

In October 1968 a group of University of Washington employees and graduate students founded a timesharing startup called The Computer Center Corporation, nick-named C-Cubed.

C-Cubed leased a PDP-10 computer from DEC - serial number 36. The deal with DEC included reduced fees in exchange for testing their operating system TOPS-10. The company started looking for testers, and it just turned out that a computer course in a local private school - Lakeside had run out of money. C-Cubed offered the students free time on their terminals in return for reporting bugs. Among the students who took up the offer were Paul Allen and Bill Gates.

They loved the computer, learned programming in PDP-10 assembly and continued using it until C-Cubed went out of business in early 1970. That was only the beginning. In November 1970 they secured a gig with Information Services Inc. to help write a payroll program in COBOL, and in late 1972 they joined a TRW Inc project to develop a real-time operating and dispatch system, (RODS) for the Bonneville Power Administration’s electrical grid. The project did not progress well, but Allen and Gates were allowed to work on their own project off hours.

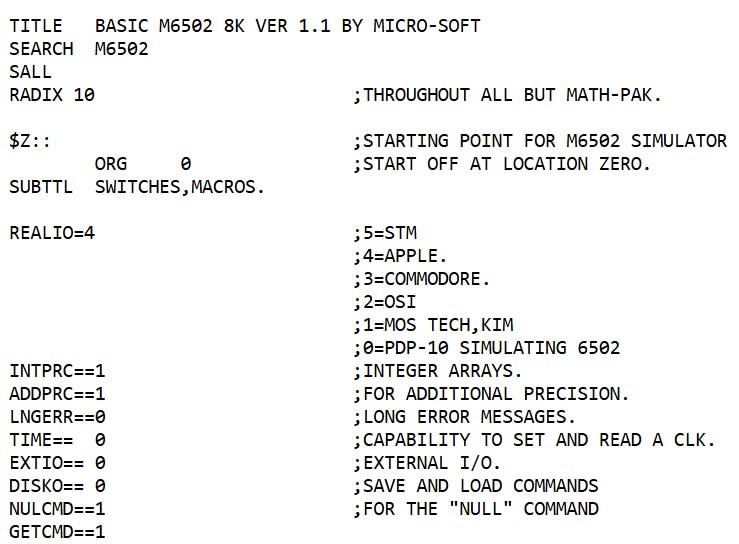

They had an idea to build a traffic control application based on Intel’s first 8-bit microprocessor: 8008. Allen built a set of tools to develop code for 8008 on PDP-10, including a simulator, cross-assembler and debugger. They eventually completed the system, called it Traf-O-Data and even sold it to three customers. The money they earned was not worth the effort, but the experience and tools they built in the process were.

In December 1974, Paul Allen bought an issue of Popular Electronics with a new computer called the Altair 8800 on the front page. By then the two friends lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts - Allen was working for Honeywell and Gates attended Harvard University. They saw an opportunity and offered to write a BASIC interpreter for the new microcomputer. The old development tools for the 8008 were adjusted to the new 8080 processor and they went to work.

They used a PDP-10 computer at Harvard’s Aiken Computation Lab, called Harv-10, on which they completed the interpreter by late February. Allen flew to New Mexico, demonstrated the software to MITS (producers of Altair), and soon after the two friends moved to Albuquerque to work on their new project full time. They started a company and called it Micro-Soft, later renamed to Microsoft.

Microsoft continued using various PDP-10 computers as their primary development machines into the 1980s until microcomputers finally became powerful enough to host productive development environments.

In June 1973 Dan Bricklin graduated from MIT with a Bachelor of Science in electrical engineering and computer science. His grades were not good enough to get him into graduate programs he was interested in, and he began looking for a job. He interviewed with Digital Equipment Corp. (DEC) and accepted a position with a group that was developing a computerized typesetter system.

The first product Bricklin worked on within DEC was TYPESET-10, a typesetting system that ran on DEC’s PDP-10 mainframes. Later he worked on a word processing system called WPS-8 that ran on DEC’s low-end PDP-8 minicomputer.

In 1976, DEC moved Bricklin’s office to New Hampshire, and he started working at a producer of cash registers called Fasfax where he led the programming department and used Forth and assembly on microcomputers.

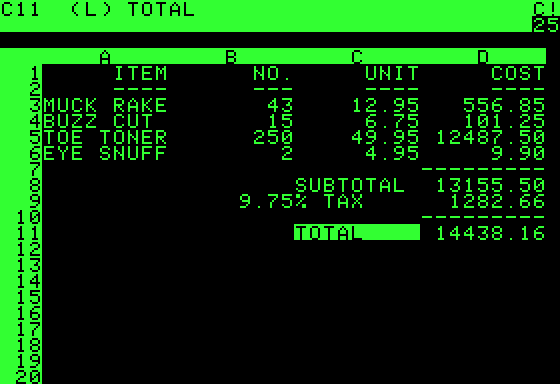

In 1977, Dan Bricklin decided to go back to school and earn an MBA from Harvard. At one lesson, in the spring of 1978, in his own words he started “daydreaming” of a calculator that could be moved around like a mouse. He decided to prototype a software version of his calculator. For that, he used Harvard’s PDP-10 timesharing computer to which he was connected via a DEC VT05 terminal and wrote the prototype in BASIC. During the development of that first prototype he decided to organize the numbers into named rows and columns.

The second prototype followed a few months later on a borrowed Apple II computer with a game paddle acting as a mouse.

The production version of VisiCalc was coded by Bricklin’s friend Bob Frankston. He did not use a PDP-10, but a similar mainframe timesharing system: MIT’s Honeywell 6180 running Multics. The main reason was that Frankston had learned how to cross-develop code for 6502 microprocessors on Multics while consulting with a small company named ECD Corporation. He worked at night when compute time was cheaper, sharing the computer with Honeywell developers who worked on the Ada programming language.

VisiCalc became the “killer app” for Apple II and the model for every spreadsheet application that followed.

.png)