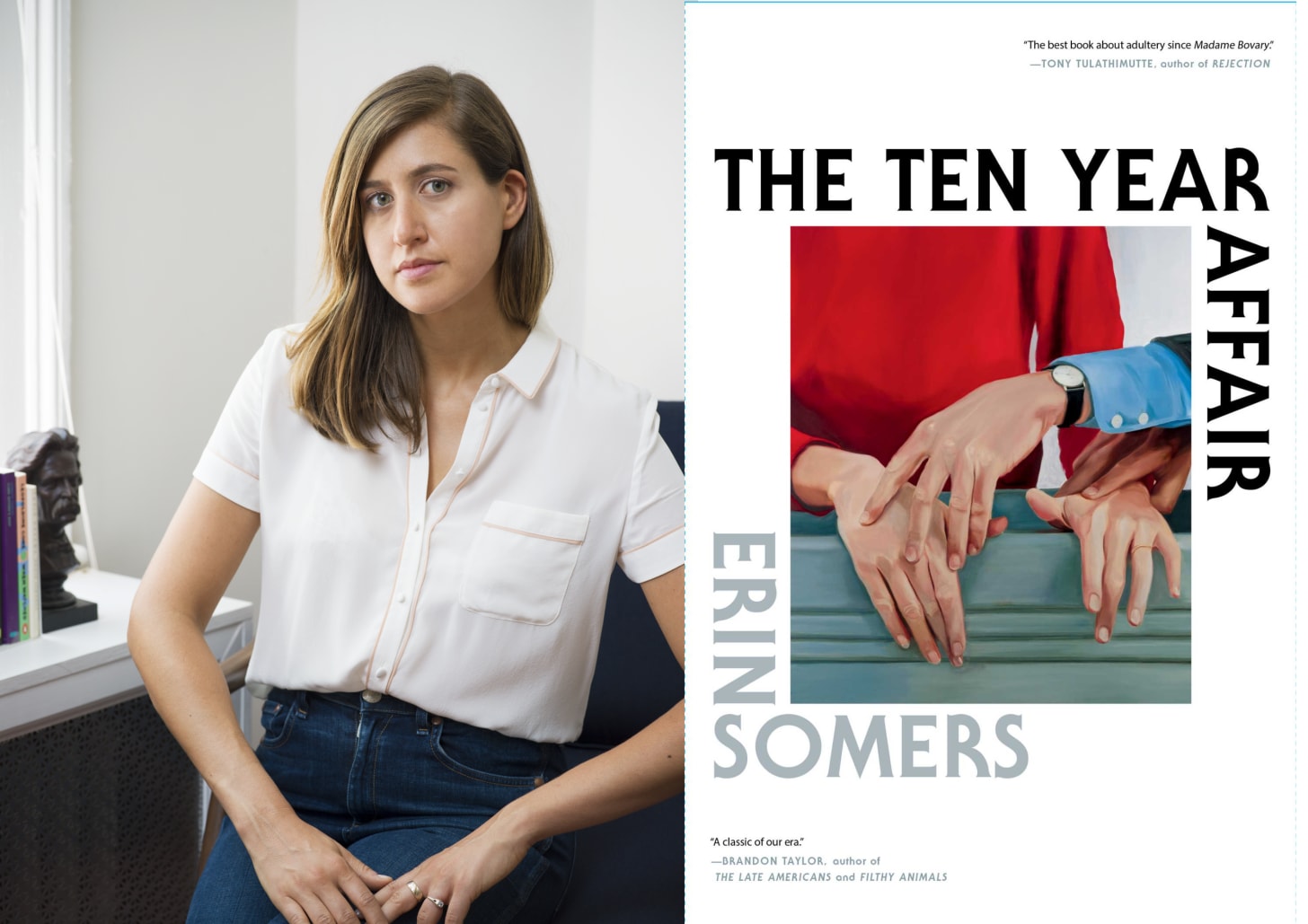

Processing is Counter Craft’s semi-regular interview series where I talk to authors about the craft and writing process behind their work. You can find previous entries here. This week, I’m excited to be talking to Erin Somers about her hilarious and poignant novel The Ten Year Affair. I first encountered Somers’s work over a decade ago when she entered and won the first (and only) fiction contest that the literary magazine I co-founded, Gigantic, ever held. Since then, Somers has published two sharply written and very funny novels: Staying Up Late with Hugo Best and now The Ten Year Affair. The latter follows Cora, a somewhat directionless millennial woman living in upstate New York with her husband and two children, who begins to live a second fantasy life where she has an affair with another local parent. Through this lens, the novel looks at millennial malaise, infidelity, modern love, and the paths we take and don’t take in life.

I talked to Somers over email about comic writing, not outlining (“too boring”), reading drafts aloud, and being “lower than a worm” while writing

The Ten Year Affair began life as a short story. It can be tricky to expand a narrative from a few pages to a few hundred pages, and you pull it off here. Can you talk about your process in expanding the story? How much of the narrative did you have to change and were there any tools (e.g., outlining) that helped you expand?

The story is about thirteen pages long, so there was a lot to do. The first thing I tried was keeping the story’s same beats and just filling it out a lot, inventing more, letting scenes go on longer. No dice. This did not work. A playful thing about the short story, the joke at the heart of it, is that the two main characters do not sleep together. At thirteen pages, that’s fine. At 300 pages it’s impossible. My agent in particular was like, “There must be sex in this novel. Please put sex in this novel!”

So then I rethought it. I don’t ever outline: too boring. I have to feel unfettered when I’m drafting instead of feeling like I’m hitting obligatory plot beats. My version of outlining is to make the structure really tight. So with this book I was like, “okay, 10 years, 10 chapters of roughly equal length.” Each chapter represents the passing of a year but it does not have to be literal, meaning, a chapter could take place over the course of twelve months, or a week, or one day (as one of them does), but then the following chapter still jumps to the next year. I also knew something structural had to happen at the end of chapter seven, the peak of Freytag’s Pyramid, if I wanted to scratch the traditional narrative itch in people’s minds. So that was the roadmap of the draft that eventually succeeded. And then the process was just making the world a lot bigger.

As an author of both stories and novels, how is your approach to those two forms similar and different?

Short story is the one true form, in my opinion. You can get a short story a lot closer to perfect than a novel. A novel is going to be flawed, and even as I know this, it sort of drives me crazy. With short story writing, if things are going well and an idea has legs, I draft a story in four or five extended sittings. Just really focused and fast. I try to draft them as clean as possible as I go. Then I’ll revise and edit over a few weeks. I don’t like to over-revise the short fiction. I try not to kill what is loose about the form, or gestural, with lengthy explanation or backstory.

With novel writing, on the other hand, I revise endlessly. Some sections take me five to eight drafts. Some I never get exactly right. In the drafting phase, I work through a novel in chronological order and write 500 words a day. That’s a number I can hit, and often exceed, even if I have work or life obligations on a certain day.

In both cases, I work best from a place of zero ego and zero hope. I call this state being “lower than a worm.” A feeling that nothing will ever come of what I’m working on is crucial. A feeling of my smallness in relation to the world. I gotta be below the dirt. I am nothing and nobody. That frees me up. Who cares what a worm thinks, you know?

The novel follows Cora, a millennial living in upstate New York with her husband and children, who imagines having an affair with another man. The parallel affair story is woven in and out of the real world narrative, intersecting and diverging in hilarious and poignant ways. How did you approach the balance of the real and “technically fictional” (as the narrator puts it) affair story? E.g., how much page space to devote to it and when to bring it back into the “real” narrative?

The way I conceptualized the second timeline was as an extension of Cora’s interiority. So whereas in a book with a more typical structure, you might have a long section of reflection, in this novel, that’s where we jump to the other world. The reflection takes place in the form of prolonged fantasy and we learn what she is thinking and feeling through what she wishes she was doing instead. The book is upfront about the second timeline being purely imagined, which made it really useful. A way to reveal what she’s thinking in any given moment without saying “Cora thought about xyz.” And the fact that it is imagined–and the reader is in on this–had a lot of comic potential, such as when Cora notes about the other world “her hair looked better over there too.”

Still, I didn’t want to overdo it with the other timeline, because I had a sense that the imagined world probably feels low stakes. So this is what I’m talking about with the five to eight drafts. I found the balance in revision. At one point, notably, I let Cora and Sam be in France for too long in the imagined world (lol) and my editor was like “cut this back??” I love being edited and my editor on this novel was the best of the best. Just so precise and brilliant and fun to collaborate with. There’s no better note than “cut this back??” Gladly!

The Ten Year Affair is a very funny book, and funny at the level of word choice and grammar. For example, the deployment of the phrase I just quoted between commas here: The other was her affair with Sam, technically fictional, its lies and illicit meetings, the racing pulse of information. Or to quote another passage:

“Now are you all still working with American toilets?” he asked her.

“Working with?”

“Using.”

“We’re using the toilets the house came with, if that’s what you mean.”

I’d love to know how you approach humor in general and at the level of syntax.

Humor in fiction comes from a few places: character, timing, and as you noted, syntax. The last two could maybe be lumped together under “sound.” I read my draft out loud, not just a single time, but every time I read through a section. My kids hear me up in my office talking to myself. If you’re trying to write something comedic, read it out loud. The ear knows what’s funny a little better than the mind.

On the syntax level, my constant exhortation to myself is, “Push for a better word.” Precision is key. Specific language works better than vague language. A word that is unexpected or particular to a certain character works better than a throw-away word. If I can surprise the reader, great. That’s the aim. Cliche is permissible only in dialogue and only if I’m sending up the character for using a cliche.

Do you take comedic inspiration from other artforms, like stand-up comedy or sketch shows?

My first book was about a comedian, and researching it, I burned out on comedy completely. I just can’t watch it. It feels like homework. The shows that remain funny to me are Strangers with Candy, Arrested Development, and 30 Rock. Those I don’t tire of. But they are different rhythmically from what I’m doing, in that they’re joke-dense and absurd. My own style I would characterize as very dry.

The art form that most inspires me outside of books is cinema. With art, I find myself chasing the feeling of reading books, where I’m absorbed but a little challenged, and the next best thing is movies. I’m inspired by, for instance, the work of Mike Leigh, who makes these small, wrenching, hilarious movies about ordinary people. I recently watched his latest movie Hard Truths. It’s so good. Exquisitely acted and understated and funny. I’ll watch a film and feel energized by how aesthetically cohesive it is. I’d like to make something that hangs together perfectly like that.

I think you’d probably agree with me that humor is often undervalued in literary fiction, at least in America. Funny books rarely win awards for example. (James winning the Pulitzer is an exception that proves the rule.) If you agree, why do you think Americans feel the comedic can’t be serious?

I was so happy to see a comedic novel on a winning streak last year. It felt like one for the home team. I think establishments earnestly want to award books that seem weighty. Nothing malicious behind it, just an over-emphasis on “importance.” I don’t even necessarily think this is wrong-headed–prizes should try to select something meaningful. Where they get into trouble is when they conflate “important topic” with “good.”

The other thing the apparatus likes to reward is the appearance of effort. If a comedic work is successful, you probably can’t see the effort. If it’s very successful, it will seem almost off-the-cuff, like it was created that moment. This is why a lot of ponderous books end up over-praised. The multi-generational saga and so on. But a light touch is hard to achieve. My thought on all this is… oh well. Important writers win prizes but funny writers get to be funny. The laugh is the reward and that’s plenty.

Since these are craft-focused interviews, I thought it might be interesting to ask about very specific craft techniques. In this novel, I noticed you often summarize dialogue mid-scene sans quotations and then throw us back into the scene with a quoted reply. To pick a favorite example, here is a part when Cora is asking her husband Eliot about an accident he had in the woods:

He glanced down at his torn sweatpants. “Oh, shit.”

He’d slightly fallen. No big deal. He’d caught himself. It was not that dark out. It was not like being locked in a trunk. It wasn’t as dark as one’s eternal grave.

“Why those comparisons?” she said.

“Just painting a picture. I could see, is my point. For the most part.”

I think this stood out to me first because it is quite funny. But also because I’ve noticed students are often hesitant to summarize in general and to summarize dialogue specifically. (I have my theories why.) Can you talk about the advantages of summary in fiction?

In certain exchanges, dialogue works better summarized. I think what happened in this specific example is I found it hard to sell Eliot saying “one’s eternal grave.” It just sounded false to me (the ear knows!). Maybe he’d say “your eternal grave,” but the formality of “one” struck me as funnier. It’s possible to sell less-than-realistic dialogue by stepping back and adding the filter of POV. The summary here is mediated by Cora, who we’re following in close third, and this helps for some reason. Maybe because it suggests the possibility that it’s not verbatim and that “one” is Cora’s own addition?

I use this technique a lot. Summary is a great tool, and rather than drudgery, I wish students could come to think of it this way. Mediation can make a scene funnier or allow you to say more. Interiority is the crux of the thing. I think you’re right about the aversion to “telling” being related to the consumption of visual media, especially streaming TV. I try to keep in mind while writing fiction to play to the medium’s strengths. Otherwise, why a novel and a sonata? Why a novel and not a painting?

There was a period when everyone was dreading an imagined onslaught of “COVID novels,” which was then followed by discourse about how COVID had been instead erased from novels and movies all together. The Ten Year Affair isn’t a “COVID novel” but does deal with COVID in ways that rang very true to me. Were you worried about including the pandemic in the novel?

It hit me at a certain point that if the book was set in our world over the course of the last 10 years I would have to include Covid. Writing around it would have been a dodge. Contemporary novels in a realistic mode have to grapple with the world as it is. So there is a short Covid section, but I tried to integrate it into the conceit. The main character gets Covid briefly and we see what this does to her imaginary life.

The hand-wringing about Covid novels is a symptom of something I see a lot, which is thinking about books as written for the month or year they are published and that’s it. But actually, someone could pick a book up in two years, or five or, if you’re lucky, 20, and the debate about whether it’s too soon to talk about whatever topic will be moot. If you read a book written about the Spanish Flu now, you wouldn’t be like “how tedious,” you’d probably feel neutral about it. So I’d rather err on the side of reflecting what happened to everyone on Earth than contort myself in an effort to avoid it.

Lastly, any advice for people who are living half their life in fantasy?

Put it to use and write a book. I’m not kidding. It’s the most gratifying thing in the world.

My new novel Metallic Realms is out in stores! Reviews have called the book “brilliant” (Esquire), “riveting” (Publishers Weekly), “hilariously clever” (Elle), “a total blast” (Chicago Tribune), “unrelentingly smart and inventive” (Locus), and “just plain wonderful” (Booklist). My previous books are the science fiction noir novel The Body Scout and the genre-bending story collection Upright Beasts. If you enjoy this newsletter, perhaps you’ll enjoy one or more of those books too.

.png)