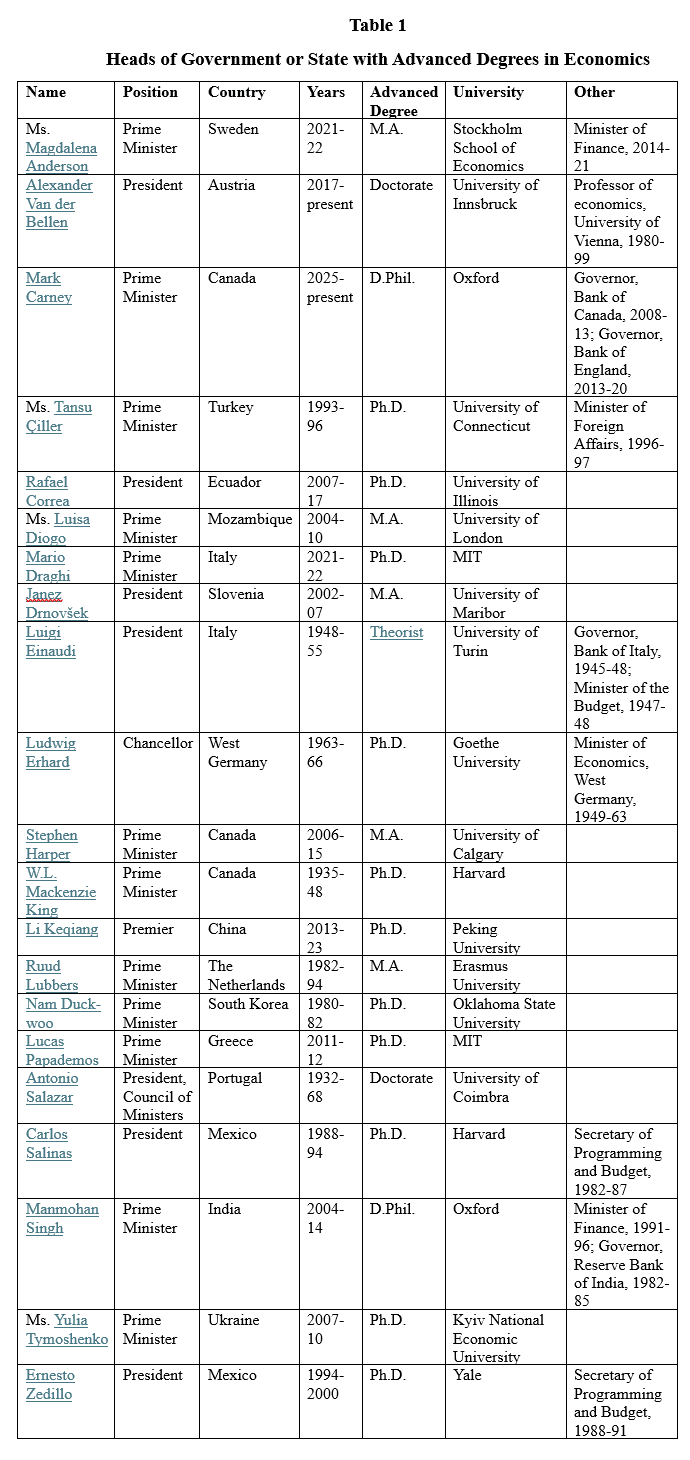

The election of Mark Carney, who holds a D.Phil. in economics from Oxford, as Prime Minister of Canada in early 2025 made me wonder whether any other professional economists had held such a position. The answer is yes. In fact, two other Canadian Prime Ministers, W.L. Mackenzie King and Stephen Harper, also had advanced degrees in economics.

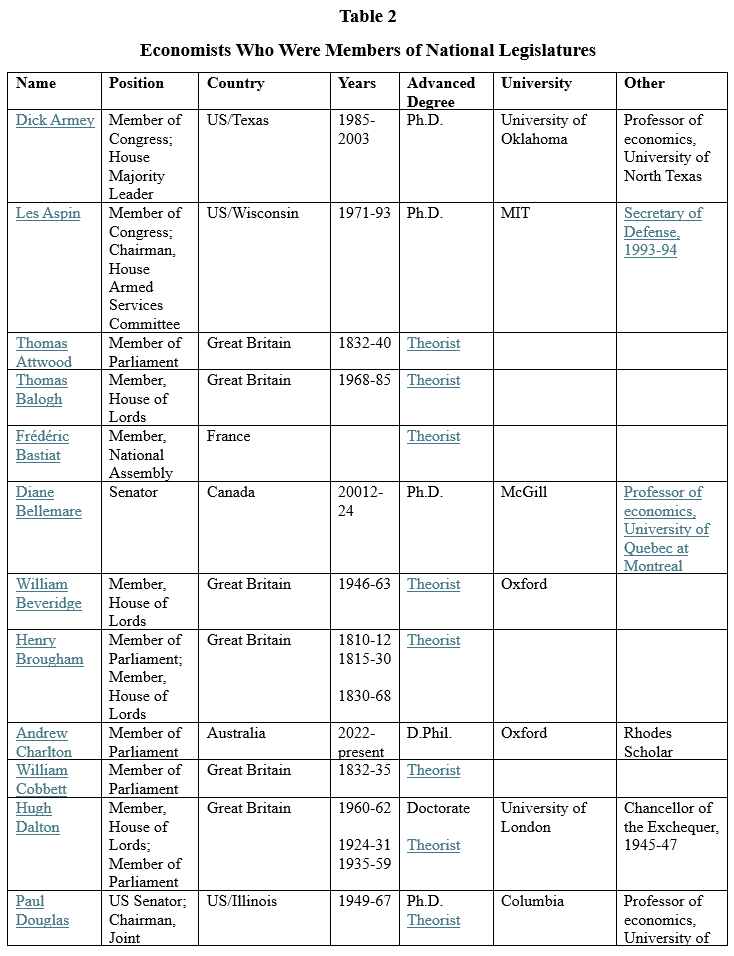

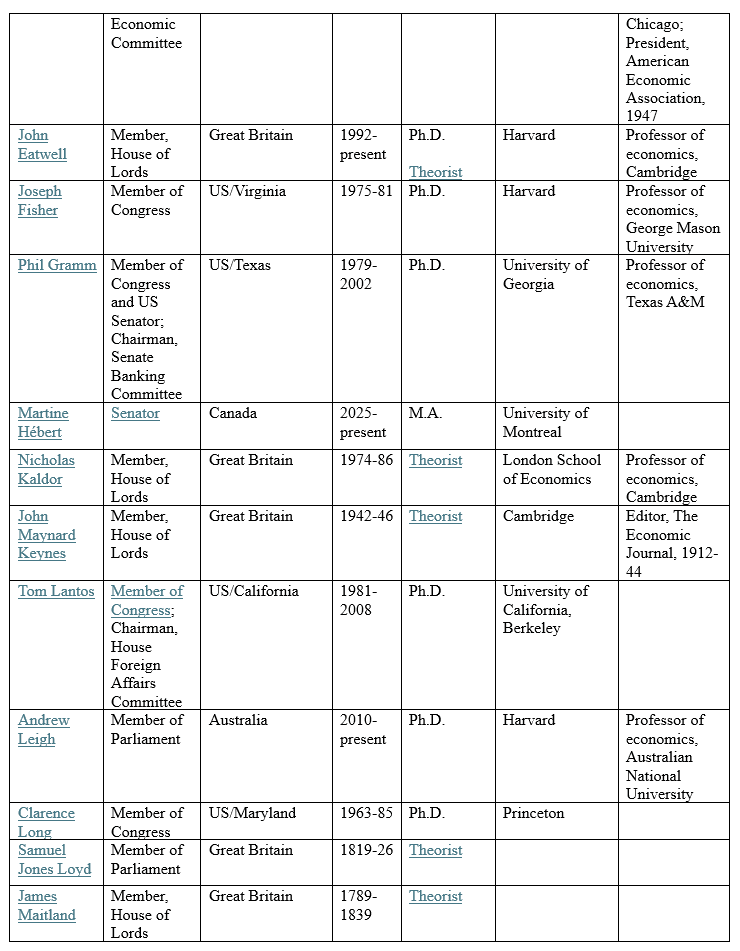

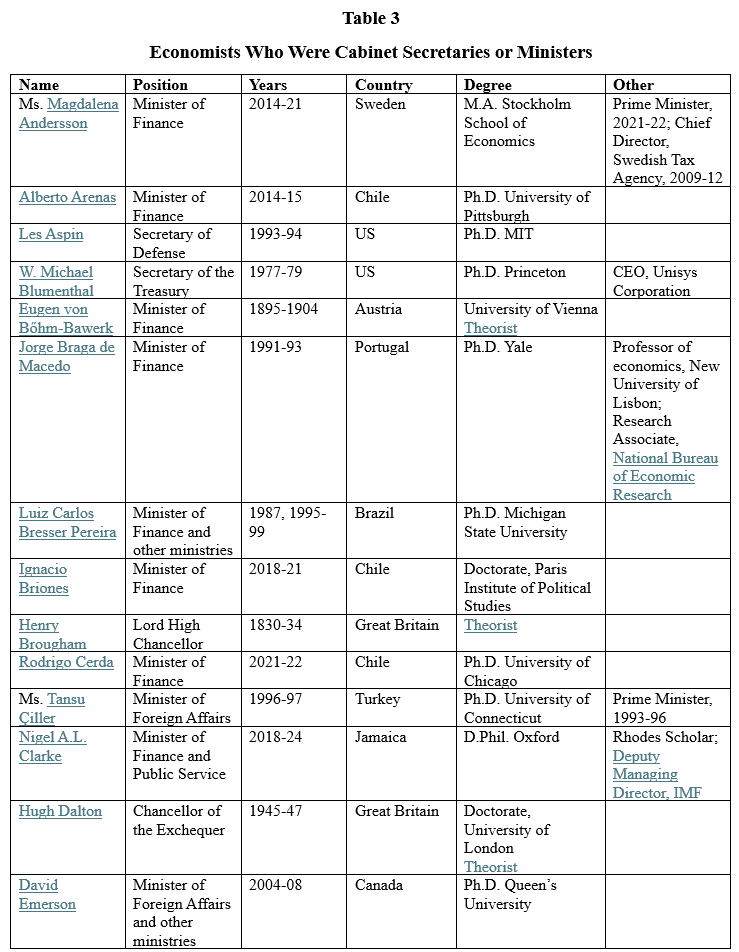

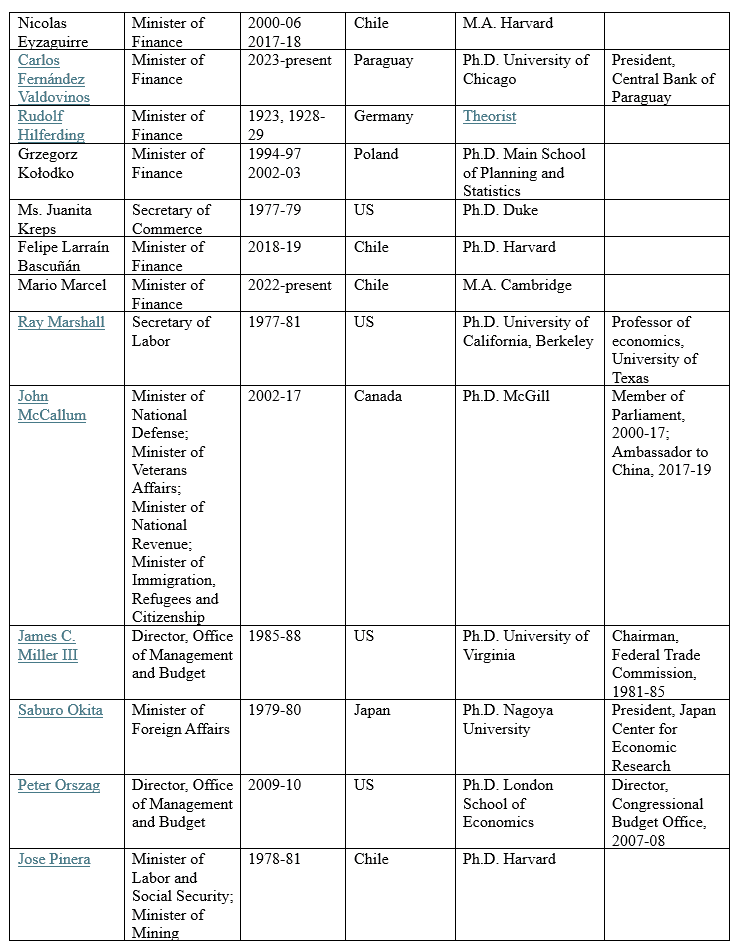

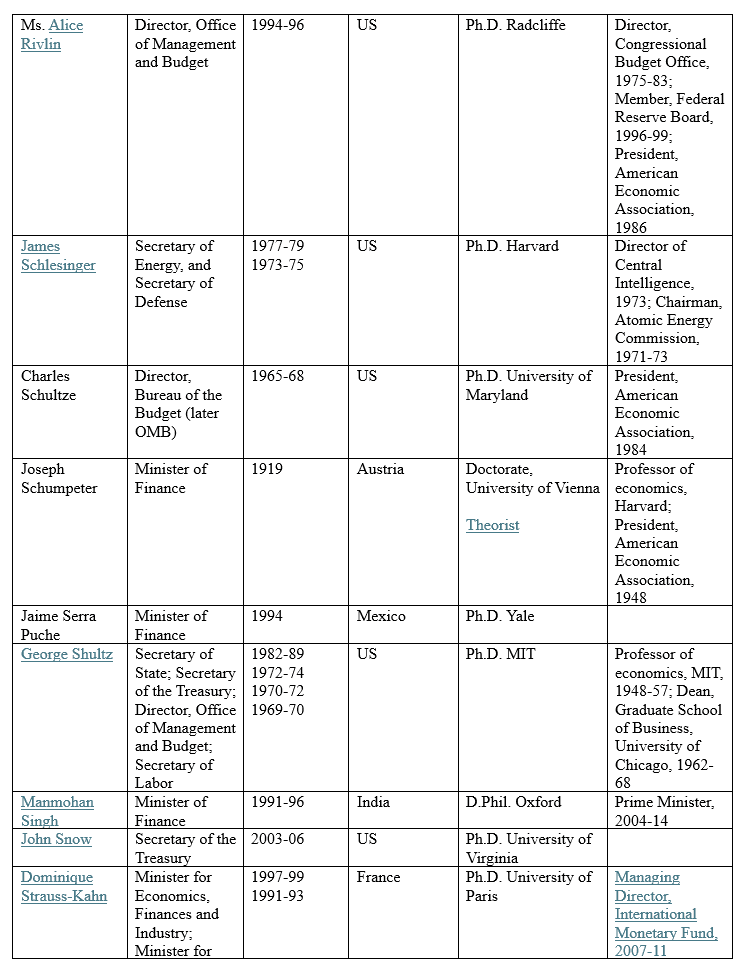

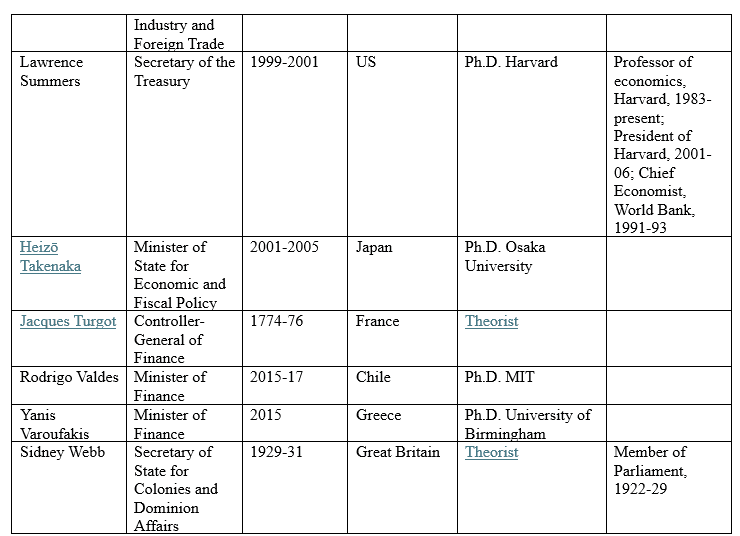

When I began this investigation, I just assumed that someone had compiled a list of economists who had held high level positions in government outside central banks or the usual economic advisory roles, such as chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers in the U.S.

What I was looking for wasn’t those holding purely advisory positions, but those wielding real political power. I had thought that an investigation of their lives in office might yield some insights into whether technical expertise in economics yielded better or worse policies than those implemented by the usual lawyers, businessmen, military men, or professional politicians.

Unfortunately, my list of economists in office grew too large for easy analysis. Although some members of my lists are very well known, both as economists and as policymakers, others are very obscure indeed. Beyond what is available on Wikipedia, a very uneven source, I could find almost nothing.

Of course, a few economist are quite famous. In Britain, both David Ricardo and John Stuart Mill served in Parliament. In Austria, both Joseph Schumpeter and Eugen von Bohm-Bawerk served as Minister of Finance. In Germany, Ludwig Erhard, architect of the postwar economic recovery, served as Chancellor after many years as Economic Minister. In Italy, Luigi Einaudi served as president after the war. In the United States, several professional economists have served as secretary of the Treasury, as head of the Office of Management, or in Congress. Two standouts are Lawrence Summers, who continues to contribute to economic debate in academia and popular debate, and Paul Douglas, co-originator of the famous Cobb-Douglas Production Function.

One problem I had from the beginning was determining who was an economist. Obviously, a Ph.D. or M.A. would be a sufficient criteria, but before World War II they weren’t required even to teach at the highest levels. John Maynard Keynes, for example, never got an advanced degree, yet dominated economic theory for 50 years or more. I utilized the so-called duck-test: if it looks like a duck, walks like a duck, talks like duck etc., it’s probably a duck. Thus, I included Carlos Salinas, president of Mexico, even though his Ph.D. is not in economics but public policy.

For those without advanced degrees but substantial accomplishments as economists, I relied heavily on the History of Economic Thought website maintained by the Institute for New Economic Thinking. All links to those labeled “theorist” are to this site.

Finally, I would emphasize that I relied largely on anecdotal evidence to find these names, and I’m sure I missed some. I am hoping that those with knowledge will contact me if they have suggested additions. I can be reached at [email protected].

I’m also looking for good biographical material about anyone on these lists. A few have full-length biographies, but few have looked deeply into their public service. At the end I have listed a few publications indicating the sorts of materials I would like to find more of before proceeding further.

I would just mention in passing that I was for some years executive director of the Joint Economic Committee of Congress and I served in senior staff positions in the White House and at the Treasury Department. In these capacities I got to know personally a number of those on these lists.

Just to repeat—this is a preliminary investigation motivated by Mark Carney’s election as Prime Minister of Canada. I am posting it now in hopes of getting feedback and finding additional names of people I may have missed.

Addendum

I missed Herbert Grubel, a Member of Parliament in Canada, 1993-97. He has a Ph.D. in economics from Yale and taught at Simon Fraser University for many years.

I also missed David Brat, a Member of Congress from 2014-2019. He holds a Ph.D. in economics from American University.

Ed Balls was a Member of Parliament in Britain from 2005-2010; and Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families from 2007-2010. He has an MPA from Harvard.

Bertil Ohlin was a member of Parliament in Sweden from 1938-1970, and Minister of Commerce and Industry, 1944-45. He shared the Nobel Prize in economics in 1977.

Ohlin’s daughter, Anne Wibble served as Minister of Finance in Sweden, 1991-94. She had a M.A. in economics from Stanford.

Gunnar Myrdal also served as Minister of Commerce and Industry in Sweden from 1945 to 1947. He shared the Nobel Prize in economics in 1974.

Select Bibliography

Alexiadou, Despina, William Spaniel, and Hakan Gunaydin. 2022. “When Technocratic Appointments Signal Credibility.” Comparative Political Studies, 55:3 (March): 386-419.

Augello, Massimo M., and Marco E.L. Guidi. 2005. Economists in Parliament in the Liberal Age (1848-1920). New York: Routledge.

Bartlett, Bruce. 2015. “The Joint Economic Committee in the Early 1980s: Keynesians versus Supply-Siders,” Journal of Policy History, 27:11 (Winter): 184-95.

Carnes, Nicholas, and Noam Lupu. 2023. “The Economic Backgrounds of Politicians.” Annual Review of Political Science, 26, pp. 253-70.

Einaudi, Luigi. 1962. “Politicians and Economists.” Il Politico, 27:2 (June): 253-63.

Fetter, Frank W. 1975. “The Influence of Economists in Parliament on British Legislation from Ricardo to John Stuart Mill.” Journal of Political Economy, 83:5 (October): 1051-64.

Grampp, William D. 1982. “Economists and Politicians: Some Cautionary History.” Review of Social Economy, 40:1 (April): 13-29.

Hallerberg, Mark, and Joachim Wehner. 2012. “The Educational Competence of Economic Policymakers in the EU.” Global Policy, 3, supp. 1 (December): 9-15.

Hallerberg, Mark, and Joachim Wehner. 2020. “When Do You Get Economists as Policy Makers?” British Journal of Political Science, 50:3 (July): 1193-1205.

Lőnnroth, Johan. 2013. “Who Came First: Politicians or Academic Economists?” History of Economic Thought and Policy, 1 (August): 121-40.

Markoff, John, and Verónica Montecinos. 1993. “The Ubiquitous Rise of Economists.” Journal of Public Policy, 13:1 (January-March): 37-68.

Mierzejewski, Alfred C. 2004. Ludwig Erhard: A Biography. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Nelson, Robert H. 1987. “The Economics Profession and the Making of Public Policy.” Journal of Economic Literature, 25:1 (March): 49-91.

Niskanen, William A. 1986. “Economists and Politicians.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 5:2 (Winter): 234-44.

Patel, Josh. 2023. “The Puzzle of Lionel Robbins: How a Neoliberal Economist Expanded Public University Education in 1960s Britain.” Twentieth Century British History, 34:2 (June): 220-45.

Pavanelli, Giovanni, and Giulia Bianchi. 2020. “The Italian Economists as Legislators and Policymakers During the Fascist Regime.” An Institutional History of Italian Economics in the Interwar Period. Vol. 2. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 143-77.

Potrafke, Niklas. 2025. “The Economic Consequences of Businesspeople in Politics: A Survey.” European Journal of Political Economy, 86 (January): 1-18.

Schultze, Charles L. 1982. “The Role and Responsibilities of the Economist in Government.” American Economic Review, 72:2 (May): 62-66.

Silvestri, Paolo. 2008. “On Einaudi’s Liberal Heritage.” History of Economic Ideas, 16:1/2, pp. 245-52.

Stolper, Wolfgang F. 1994. Joseph Alois Schumpeter: The Public Life of a Private Man. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Swedberg, Richard. 1991. Schumpeter: A Biography. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Wehner, Joachim, and Mark Hallerberg. 2013. “The Technical Competence of Economic Policymakers.” VoxEU (February 14).

Whitaker, Reginald. 1977. “The Liberal Corporatist Ideas of Mackenzie King.” Labour/Le Travail, 2, pp. 137-69.

.png)

![The Violators by Censor Design – C64 2025 [video]](https://www.youtube.com/img/desktop/supported_browsers/chrome.png)