In the spring of 1940, a 36-year-old junior psychology professor named Burrhus Frederick Skinner looked out the window of a train to Chicago.

Skinner would one day become the most famous psychologist in America. But back then, he had recently published a groundbreaking work called The Behavior of Organisms, the result of years of studying rats in Harvard’s laboratories. And, at the start of the second World War — the war physics won — rats running mazes in labs didn’t seem super relevant. As he rode the train, he was pondering how to change that.

“I saw a flock of birds lifting and wheeling in formation as they flew alongside the train,” he wrote in his autobiography. “Suddenly I saw them as ‘devices’ with excellent vision and extraordinary maneuverability.”

And then he thought: “Could they not guide a missile?”

At the start of a major aerial war, the air force needed some reliable way to guide their bombs. Birds guide their flight all the time. If behaviorism was all about the control of animal behavior, maybe the guy who wrote the book on the Behavior of Organisms could train the pigeons to operate a missile.

This sounds crazy, but so did an atomic bomb.

Skinner wrote up a proposal for the military. And as with the greatest academic works, he gave it a phenomenally bland title. “Description of a Plan for Directing a Bomb at a Target.”

It would come to be known as Project Pigeon.

Skinner bought some pigeons from a shop back home in Minneapolis that sold birds to Chinese restaurants. He got some money from General Mills’ research division (yes, the company that also makes Cheerios, but remember there was a war on and everybody was doing their part), and went to work in secret. He was furnished a laboratory of sorts — the top floor of an abandoned flour mill, reachable only by a primitive and life-threatening elevator.

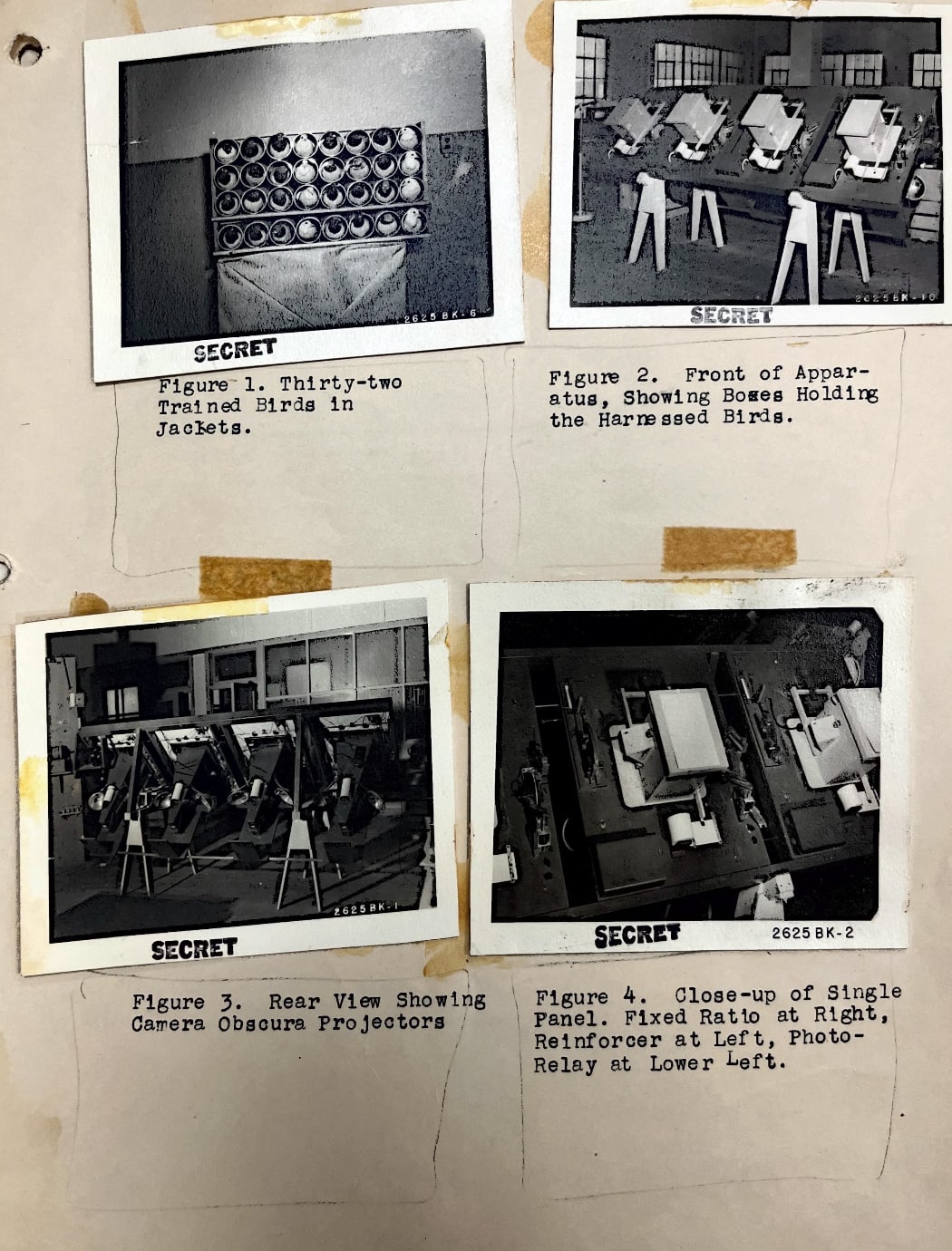

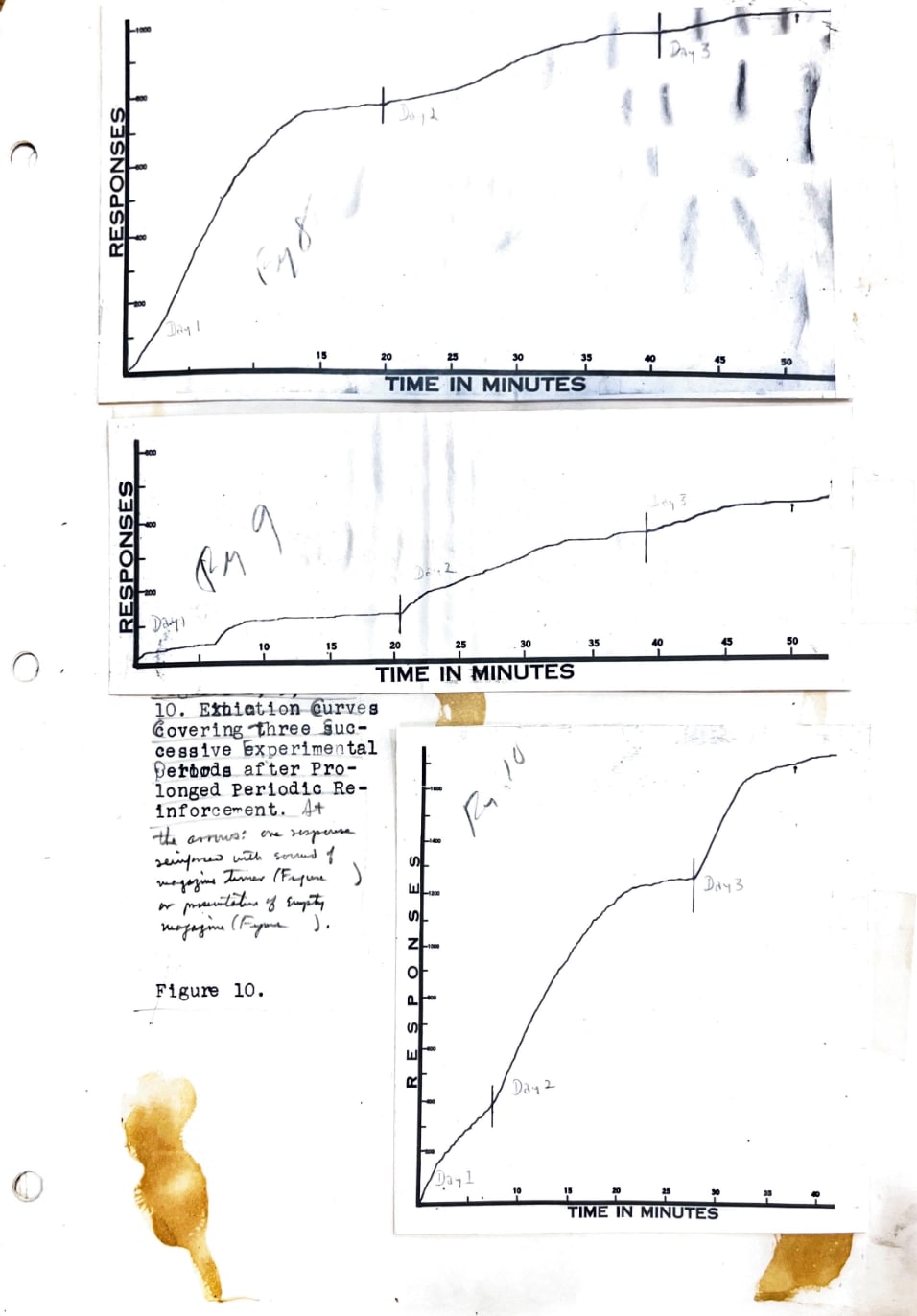

Skinner’s idea was that you could reinforce any animal behavior with food. If you could reinforce a pigeon to peck at a target on a screen and construct a system that translated the bird’s pecks into mechanical signals, you could have a pigeon guide a bomb. Skinner got some research assistants. Two were of particular note: Marian and Keller Breland, a young couple of psychologists who’d just gotten married the year before. They began studying the exact ratio of response and reward by which the appropriate pecking behavior could be taught.

They also worked with General Mills to design a system for translating the bird’s movements into mechanical steering guidance. Marian would cut the toes off men’s socks and slide the birds into them. They tied their legs with shoestring.

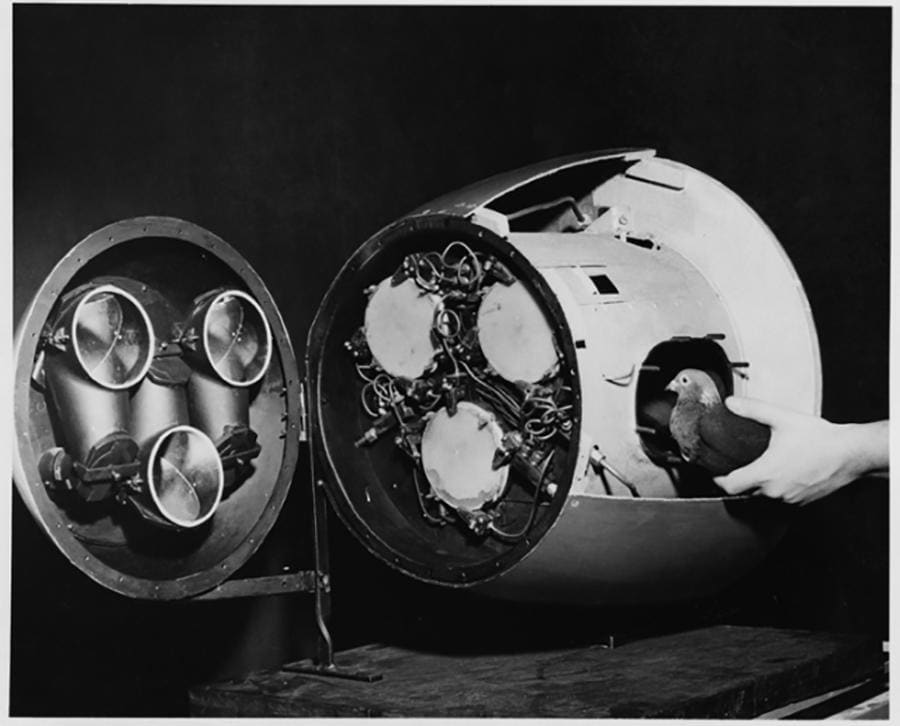

After some trial and error, a final harness and steering system was developed with help from the General Mills engineer who had designed, among other things, the Toastmaster:

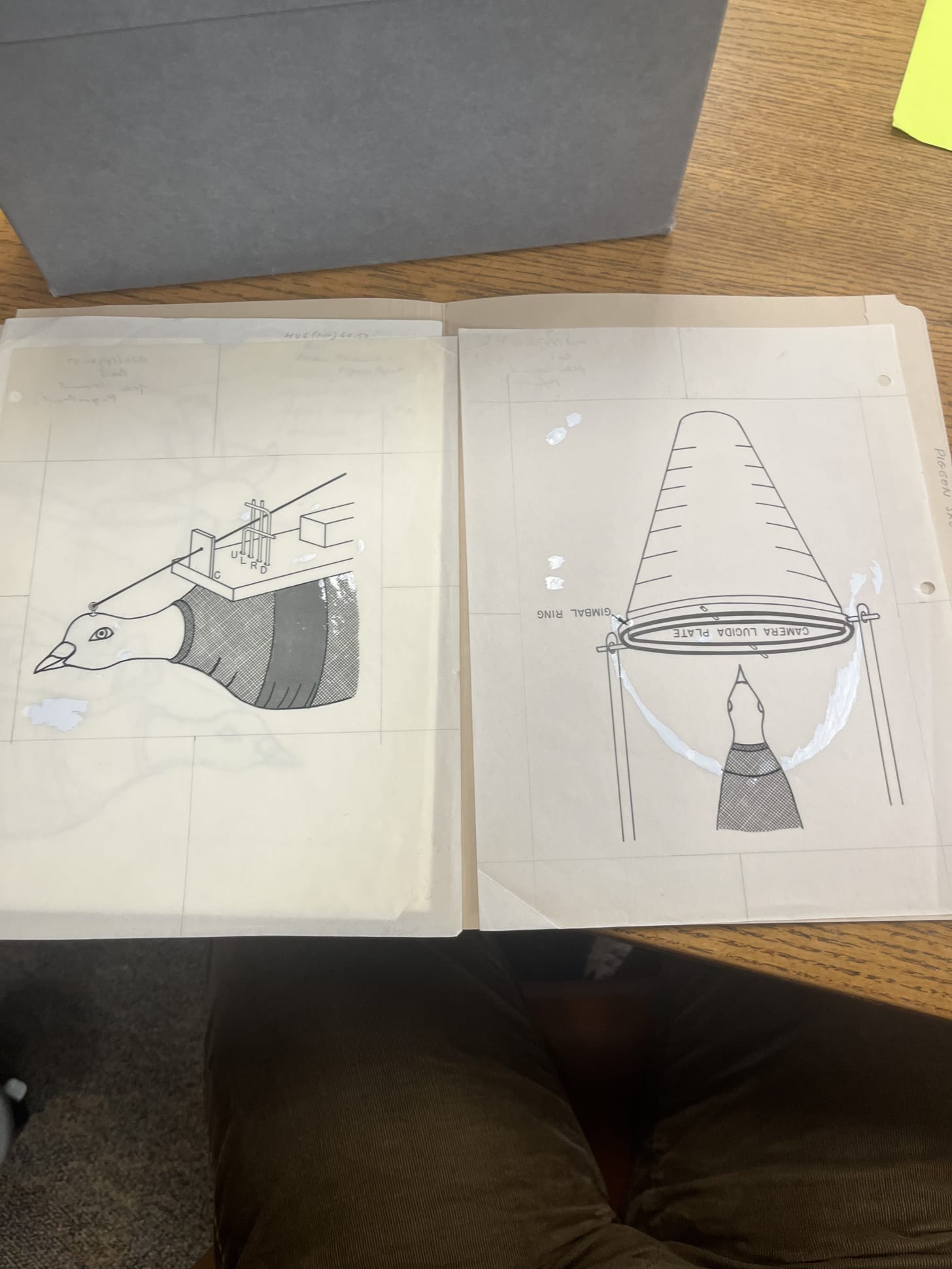

The idea was that there’d be a little lens in the nose cone of a falling bomb, which would project the image of the target below onto a screen in front of a bird. The screen had a conductive electrical circuit running through it that closed when the pigeon pecked, sending a signal to the fins of the bomb. You would train one or several pigeon pilots to keep pecking at the screen without reward by slowly increasing the intervals between a peck and food, until the bird just kept pecking and pecking.

Then, once in the bomb, it would keep pecking at the target, expecting its food, until eventually…kaboom.

This was promising work.

The Office of Scientific Research and Development gave them a grant. Skinner and the Brelands began testing their birds under increasingly unpleasant circumstances to prepare them for war — gassing them, firing pistols near them, and slipping them tincture of marijuana. The birds were unfazed. Pigeons, it turns out, will do anything for hemp seed.

And so it was that a bunch of stoned pigeons became a going concern for the U.S. military right around when the Manhattan Project was getting underway.

The behaviorists were confident in the project. But in the end, it wound up being too eccentric even for the U.S. military, which preferred to put its faith in analog computers like the Norden bombsight, even though its own track record was dubious.

Project Pigeon, though, left us with three rather significant cultural legacies.

The first came through the Brelands, Skinner’s research assistants. Inspired by the project, but broke, they dropped out of graduate school and began trying to figure out how they could capitalize on the principles of behaviorism.

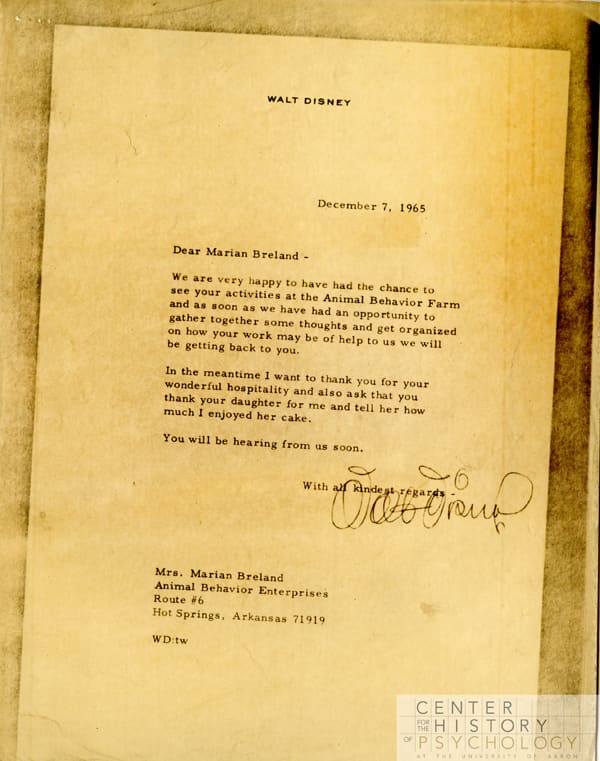

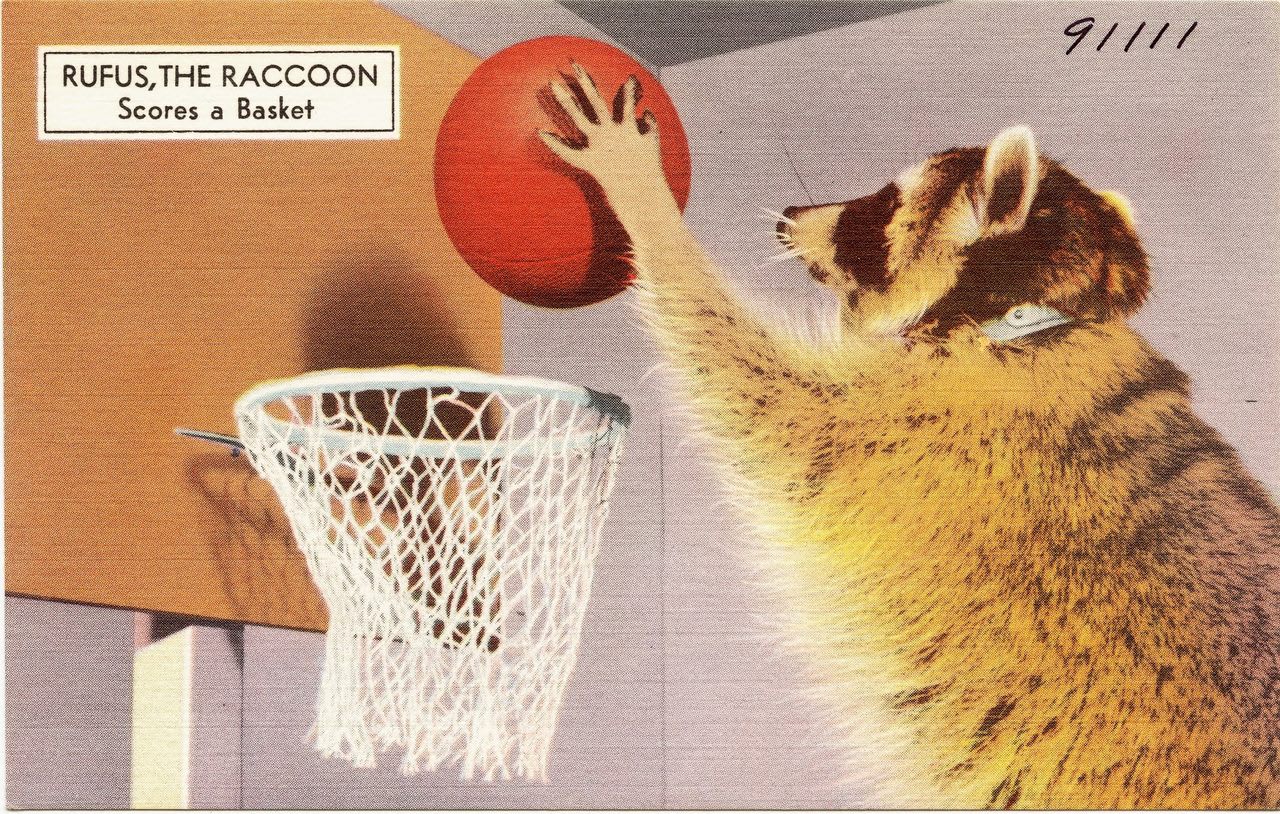

They moved to Hot Springs, Arkansas, and launched Animal Behavior Enterprises. The business used Skinner’s reinforcement ratios to train animals in commercials and theme park shows (as well as for the military). Clients included the Grand Old Opry. Sea World. Walt Disney even came by for advice on his parks.

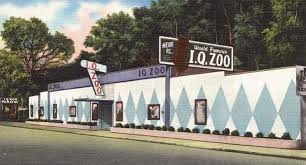

To drum up business and show how you could use the universal laws of behaviorism to train any animal, they also opened up a roadside attraction called the IQ Zoo. Big hit with the children of Hot Springs.

What’s interesting to me is: In the late 20th century, a lot of popular media concerning animals doing funny things came to us via the Brelands, thanks to Project Pigeon. And the implicit message of those funny animals was always one of mastery — we humans can make animals do anything.

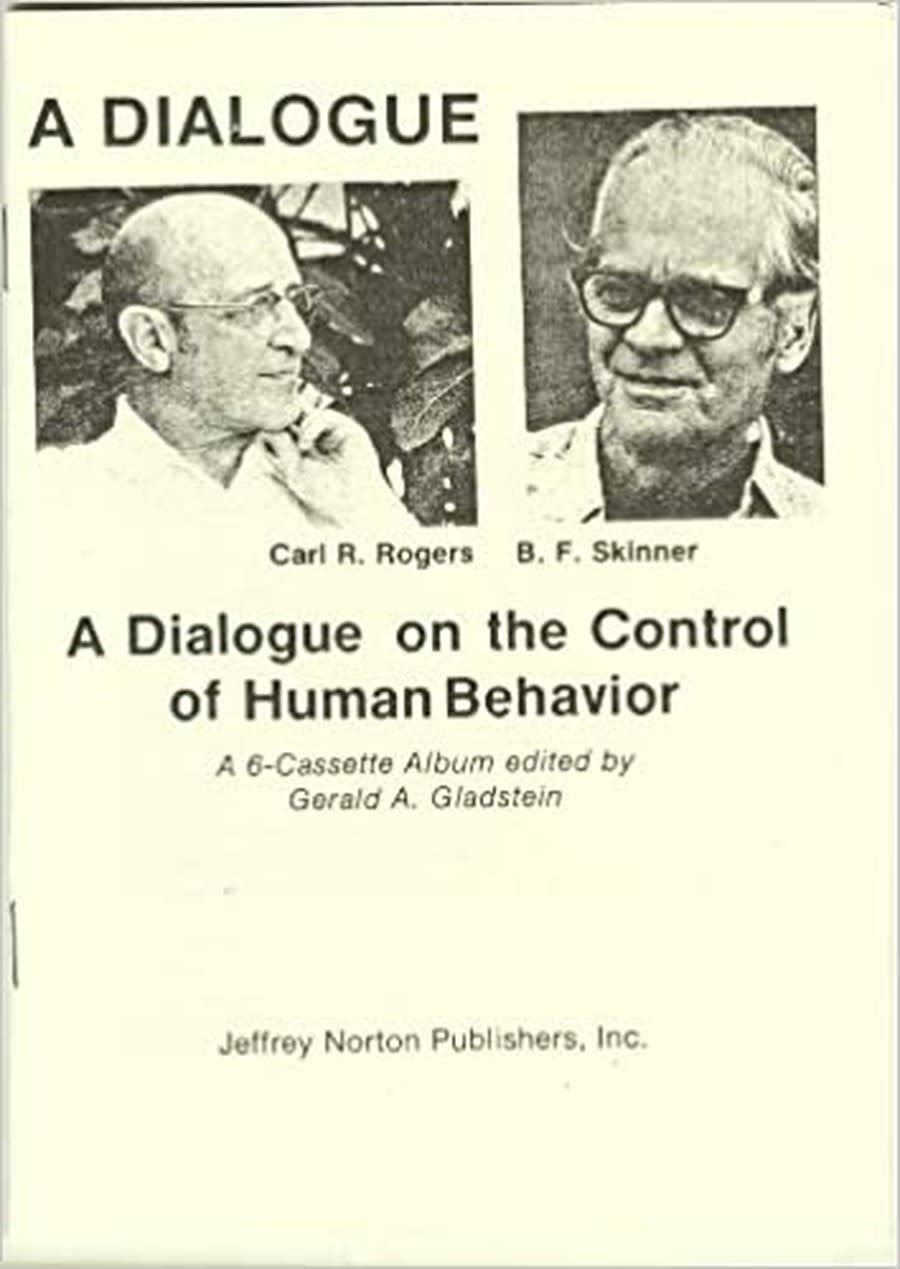

The second legacy was with Skinner. As the historian of psychology James Capshew argued, Skinner’s wartime research — beginning with Project Pigeon — is the thing that leads him from academic lab rat to Big Thinker.

“Before the war, Skinner was reluctant to venture very far outside the academic laboratory. He was a scientific purist who resisted extrapolating the results of his animal experimentation to the realm of human behavior. After the war, he attempted to make such connections boldly explicit, arguing that the scientific principles of behaviorism had widespread applicability to human affairs. By the 1950s Skinner had emerged as an advocate for the use of operant conditioning techniques for the control of individual and group behavior in a variety of settings and promoted applications ranging from teaching machines to the design of entire societies”

I am broadly critical of this intellectual project and its rather dismal view of human nature (even though it was, by its own lights, utopian). Reinforcement learning does work on humans, but it’s not a sufficient explanation for why people do what they do — it’s reductive, and tends to encourage technocratic, or nudge-type thinking.

But it grows out of that pigeon moment. And as with the Brelands, the message is mastery: Humans are like pigeons. They can be made to do anything.

The final legacy is in your pocket.

“The conductive touchscreen display technology the pigeons used made its way into early radar consoles and is the ancestor of our modern touchscreen phones and tablets,” writes Keith Martin, supervisory librarian for the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

“So, think about Skinner and his trained pigeons the next time you find yourself pecking at your smartphone, searching for a delectable little electronic reward.”

Peck, peck, peck…kaboom.

.png)