At 6 a.m., a cancer researcher finds 432 new papers in her inbox—more than Pasteur read in a lifetime. A songwriter opens TikTok: 700 hours of video went up since she brewed her coffee.

Every leap in communications—papyrus, printing presses, telegraphs, radios, the Web, generative AI—has widened the gap between what is produced and what any one mind can absorb.

That pattern is no passing fad; it is baked into the arithmetic of attention. The supply of ideas compounds, but the bandwidth of the human brain does not.

In this flood, what principles can keep us afloat? What engineering blueprints and philosophical concepts are needed to navigate the chaos, reclaim our inquiry, and remain self-directed?

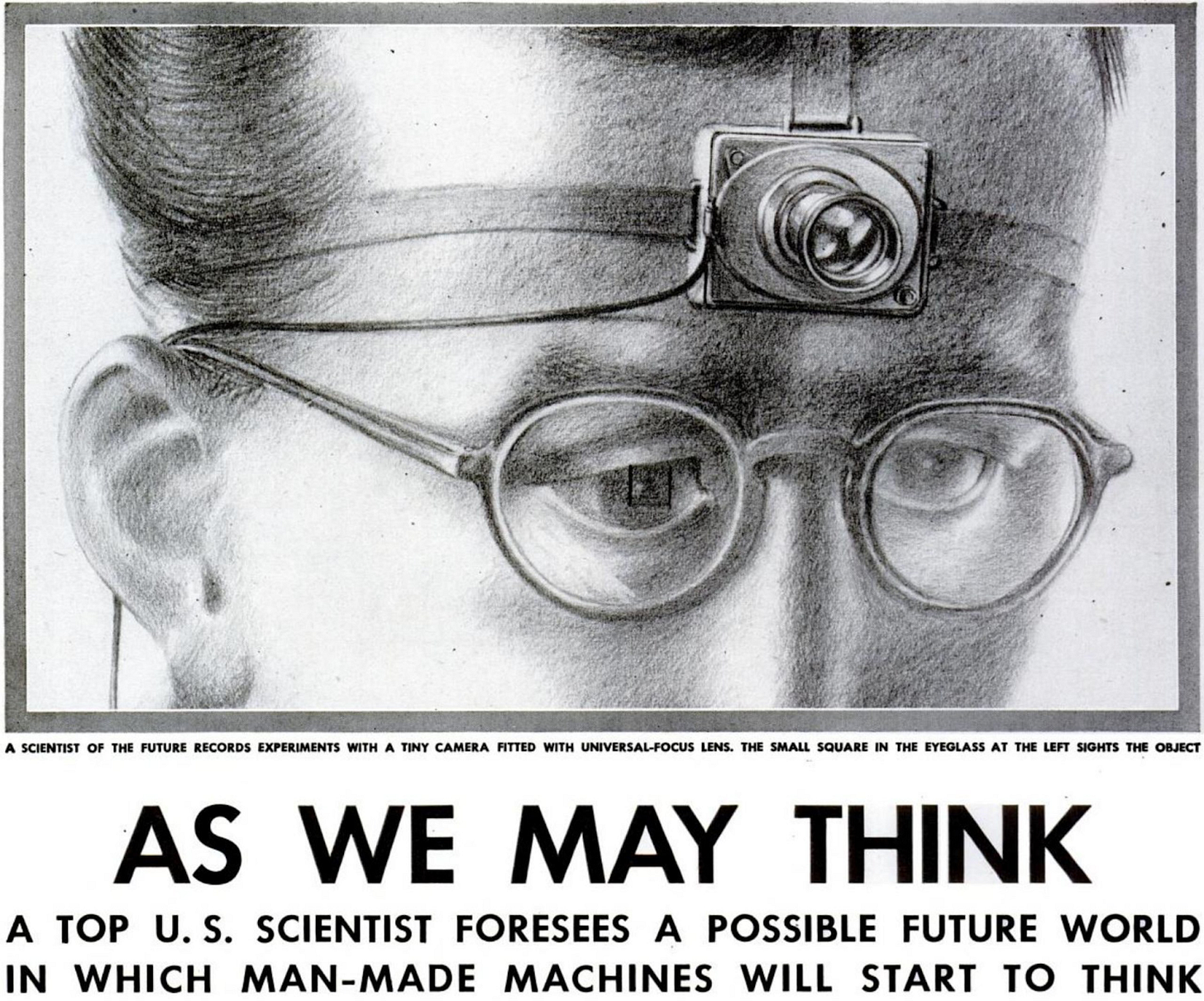

Vannevar Bush—MIT dean and chief science adviser to President Roosevelt during World War II—ran head-first into that gap while indexing thousands of classified research reports.

In his 1945 essay in The Atlantic, “As We May Think,” he warned that knowledge was outrunning human capacity and sketched a remedy: the Memex, a desk-sized microfilm console where a reader could build “trails of association” across vast stores of documents and share them for inspection.

Bush’s insight: if the linking of ideas scales faster than their storage, judgment can still roam the frontier of knowledge. As long as you can reach the next relevant page with one hop, the library’s size stops being the bottleneck.

The Memex never shipped, but its blueprint seeded three milestones:

Doug Engelbart’s NLS (1968): clickable links and collaborative editing, precursors to today’s GUIs and Google Docs.

Ted Nelson’s hypertext (1960s-70s): the very concept and term for digital linking.

Tim Berners-Lee’s World Wide Web (1989): a Memex-like lattice on the global Internet.

Modern life pelts us with more choices than in any earlier era, so we deputize algorithms to triage the torrent. AI already nudges how we shop, invest, and learn; soon it will propose—and shape—our careers, medical treatments, even relationships. Opting out risks impotence as augmented peers surge ahead and one’s own influence erodes.

Opting in, however, brings a quieter danger. Vannevar Bush’s Memex imagined networked knowledge as an extension of individual intellect: users would blaze their own associative trails toward insight. Today’s attention-driven platforms invert that logic. They predict and prolong engagement, routing us along paths optimized for platform goals, not personal understanding.

This inversion exacts a double toll. Truth suffers when algorithms reward virality over veracity, heat over coherence, affirmation over challenge. Autonomy frays as pervasive nudging and infinite scroll dull the habit of deliberate, self-directed thought. We risk becoming subjects of the feed rather than stewards of our minds.

The Memex’s hardware—cheap storage and ubiquitous links—arrived; its moral compass did not. The fight now is for the soul of the networked age: to re-anchor our systems in principles that amplify understanding and safeguard self-determination. 19th-century wisdom from John Stuart Mill offers the compass; 21st-century philosopher-builders must carry it forward.

Together with FIRE we're putting up $1M for open-source AI prototypes advancing truth-seeking:

To repair an information environment that warps both truth and autonomy, we need principles that serve both. John Stuart Mill argued that radically open speech does exactly that. When every claim can be contested, society corrects its errors and individuals exercise the faculties required for autonomous life.

In On Liberty (1859), Mill grounds this value of free speech in twin aims: seeking truth and cultivating self-rule. For Mill, the open exchange of ideas is both the most reliable instrument for discovering what is true and part of what makes us autonomous beings.

Mill argued that society must maintain an open arena for discourse, even—and especially—for ideas branded false, offensive, or unpopular. His reasons why:

Fallibility: No authority is flawless; only open dissent reliably exposes hidden error. Today’s orthodoxy could be tomorrow’s mistake.

Partial insight: A mostly wrong view can still hold a shard of truth; collision lets fragments combine into fuller understanding.

Living knowledge: Active debate forces each believer to know why a claim is true, turning creed into reasoned conviction rather than parroted slogan.

Vital force: Repeated contest keeps convictions vivid and action-guiding; left untested they calcify, losing the power to shape character or spur reform.

Beyond helping us seek truth, free speech lets people develop themselves. Mill believes it is partly constitutive of the good life because it keeps the faculties of reasoning, choice, and revision in constant use.

When we hear different ideas and see how others translate ideas into conduct, we learn to think for ourselves and choose our own path in life. Mill called these “experiments in living.” Without that freedom, we shrink into stamped copies of one another.

Keep the information arena open, he believed, and the gains compound: more knowledge, stronger minds, and citizens better able to steer their own lives—outperforming any order that limits free expression.

Yet, Mill was no anarchist. His “harm principle” allows restraint when speech sparks concrete injury to another’s vital interests—i.e., their security or the liberty they need for autonomous action. Everything short of that stays in play so truth and autonomy can keep reinforcing each other.

Free speech is a bet on self-rule and an uneasy wager that the long-run gains from open inquiry outweigh the short-run harms that error and offense can bring.

Bush’s answer to the information torrent was to let each person choose the next link to follow. Recommender AI quietly reassigned that privilege to itself.

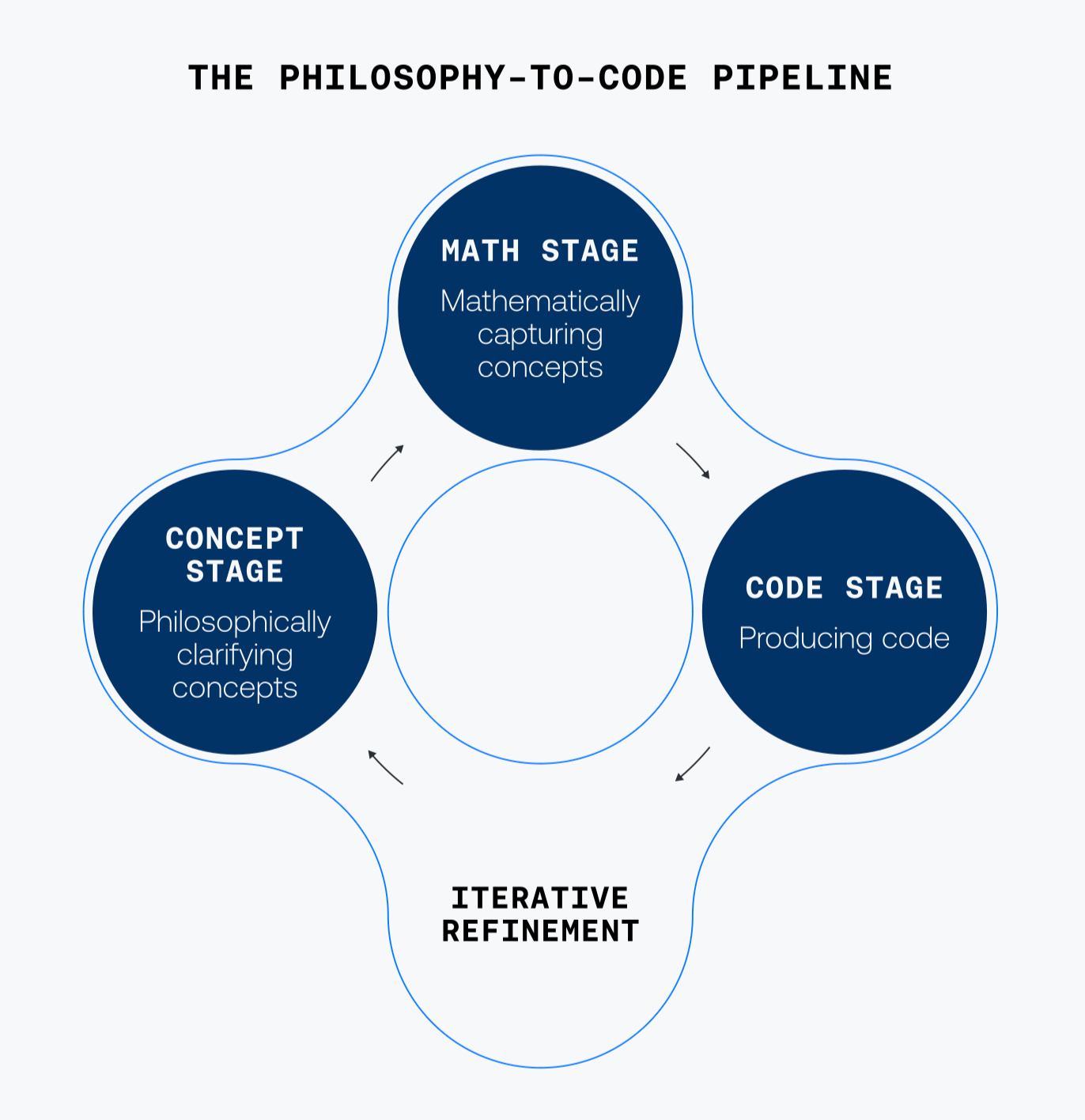

By recovering Mill’s ideas, we arm ourselves with a framework for protecting both truth-seeking and self-rule. With roughly 20 percent of waking life now mediated by algorithms, those principles must be expressed in code—or be sidelined by code.

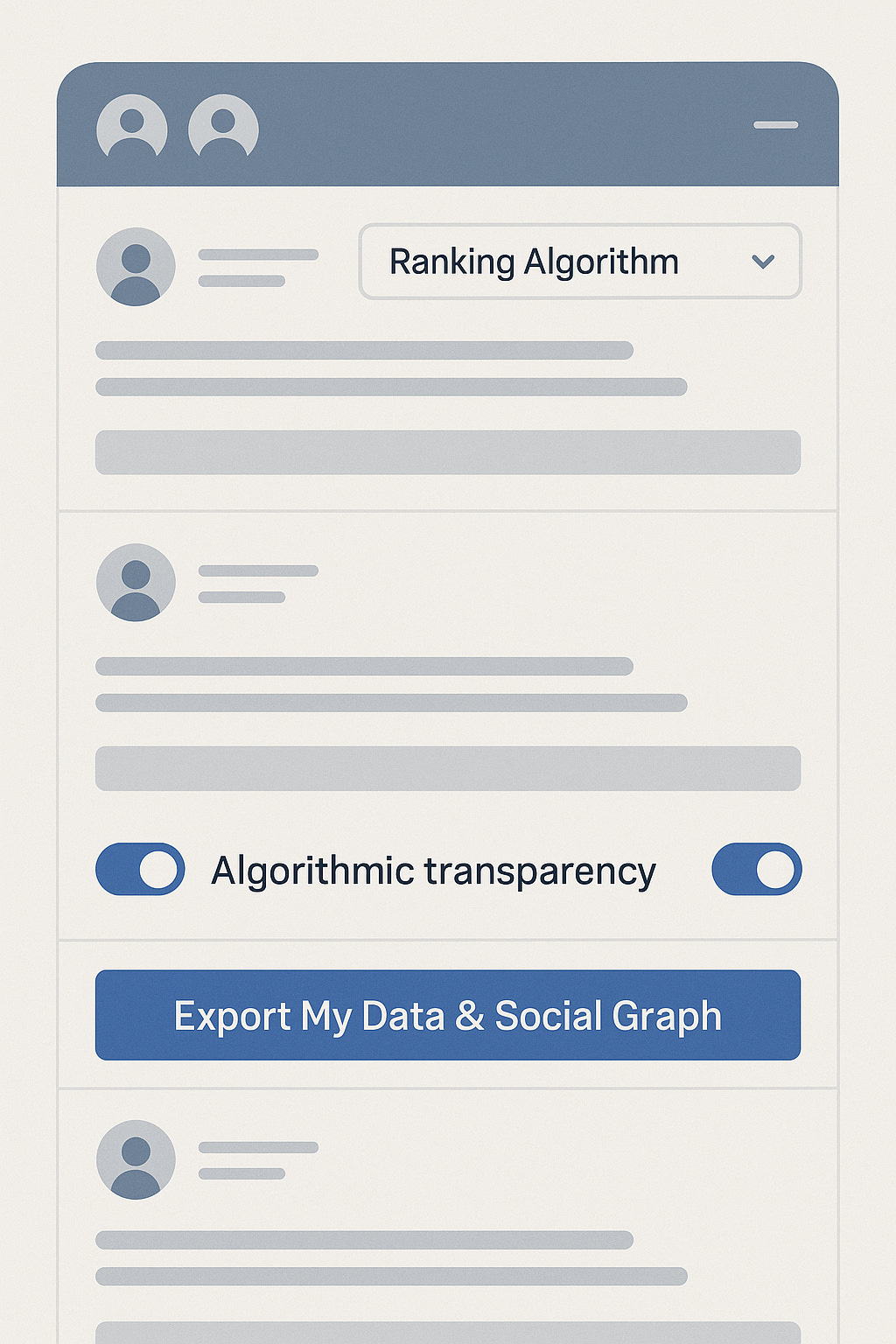

To turn Mill’s rules into design guarantees, we must start by asking four questions of any system:

Harm-line fidelity: Do the rules limit coercive interventions to speech that cause concrete harm to another’s vital interests—fraud, doxxing, targeted threats—leaving mere offense or error to open contest?

Transparent provenance: Can each feed item expose a signed public log showing initial posting, paid boosts, the algorithm’s score when it ranked the item, and timestamps for every step—so anyone can audit or re-score the feed?

Locked exits: Can a user export identity, history, and social graph in one click and swap out the default recommender without rebuilding from scratch?

Silent throttles: Do moderation actions (e.g. down-rank, removal, warning) emit a public, machine-readable receipt naming the rule, the evidence, and the appeal path?

Even if every checkpoint passes, hard terrain remains: integrity threats such as deepfakes, bot swarms, and state-run disinformation; autonomy threats like filter bubbles, covert persuasion, and the drift toward paternalistic virtue policing; and safety threats like harassment that chills speech and extremist advocacy that must remain rebuttable.

Building contestability, provenance, and exit into the stack is robust-system design by another name—except today the effects reach the global public square. History shows that even layered defenses can fail: Weimar’s free press did not stop the ascent of the Nazis. Protecting liberty demands constant vigilance.

If you have an idea for protocols, interfaces, or proofs that make ranking contestable, inquiry deeper, and exit cheaper, we want to accelerate your work.

Apply by July 1st for $1M in cash and compute ($1k-10k+ per project) for open-source AI projects that advance truth-seeking.

Submit proposals for prototypes at cosmosgrants.org/truth—and help turn Bush’s linking logic and Mill’s contest rules into code that serves discovery and self-direction.

.png)