Last week I participated in a panel discussion on AI as part of a private event in New Zealand. The organizers asked me to kick it off by talking for ten minutes, so I pulled together a few ideas on the topic, which I’m going to present in lightly edited form here. The organizers specifically wanted to think in big-picture terms so as to avoid getting fixated on rapidly changing current events, and I think that this reflects that. The objective was to get participants thinking and talking, so I tried to present one or two notions that might be thought-provoking rather than trying to make some kind of heavy ex cathedra statement—which I’m not really qualified to do anyway.

The event was held under the Chatham House Rule, so I’m free to repeat what I said but not to divulge the identities of other participants or to repeat what they said.

For the average person, AI is synonymous with large language models that have become available in the last couple of years through easy-to-use prompt-based interfaces. These have given non-technical users the ability to generate texts, images, and even movies that would have been beyond their reach before. Or maybe it’s more accurate to say that they’d have had to actually learn how to write, paint, or direct films in order to produce anything of the kind. I see parallels between these and the hydrogen bomb tests that were conducted in your back yard during the 1950s. The advent of nuclear weapons at Hiroshima and Nagasaki came as a complete surprise to the average person. In fact, though, the neutron had been discovered in 1932 and work had been underway for decades to learn more about nuclear processes and find useful applications, some of which had already become available. The eruption onto the scene of nuclear bombs suddenly focused the world’s attention on this hitherto obscure scientific discipline and made physicists into important people with weighty responsibilities. The arms race that followed, in which the United States and the USSR spent billions trying to out-do each other in the obliteration of South Pacific atolls, made it seem as if these spectacular explosions were the only thing one could actually do with nuclear science. But looking at those black-and-white images of mushroom clouds over the Pacific, ordinary people might have reflected that some of the earlier and more mundane applications, such as radium watch dials that enabled you to tell what time it was in the dark, x-rays for diagnosing ailments without surgery, and treatments for cancer, seemed a lot more useful and a lot less threatening. Likewise today a graphic artist who is faced with the prospect of his or her career being obliterated under an AI mushroom cloud might take a dim view of such technologies, without perhaps being aware that AI can be used in less obvious but more beneficial ways.

Maybe a useful way to think about what it would be like to coexist in a world that includes intelligences that aren’t human is to consider the fact that we’ve been doing exactly that for long as we’ve existed, because we live among animals. Animals have intelligences of many different kinds. We’re used to thinking of them as being less intelligent than we are, and that’s usually not wrong, but it might be better to think of them as having different sorts of intelligence, because they’ve evolved to do different things. We know for example that crows and ravens are unbelievably intelligent considering how physically small their brains are compared to ours. Dragonflies have been around for hundreds of millions of years and are exquisitely highly evolved to carry out their primary function of eating other bugs. Sheepdogs can herd sheep better than any human. Bats can do something that we can’t even begin to understand, which is to see with their ears in the dark. And so on.

I can think of three axes along which we might plot these intelligences. One is how much we matter to them. At one extreme we might put dragonflies, which probably don’t even know that we exist. A dragonfly can see a human if one happens to be nearby, but it probably looks to them as a cloud formation in the sky looks to us: something extremely large and slow-moving and usually too far away to matter. Creatures that live in the deep ocean, even if they’re highly intelligent, such as octopi, probably go their whole lives without coming within miles of a human being. Midway along this axis would be wild animals, such as crows and ravens, who are obviously capable of recognizing humans, not just as a species but as individuals, and seem to know something about us. Moving on from there we have domesticated animals. We matter a lot to cows and sheep since they depend on us for food and protection. Nevertheless, they don’t live with us, and some of them, such as horses, can actually survive in the wild after jumping the fence. Some breeds of of dogs can also survive without us if they have to. Finally we have obligate domestic animals such as lapdogs that wouldn’t survive for ten minutes in the wild.

A second axis is to what degree these animals have a theory of the human mind. How much do they know about what is going on in our minds? Consider for example wolves vs. domesticated dogs. These are almost identical in terms of their DNA and have many social behaviors in common, but wolves don’t understand humans as anything other than edible but potentially dangerous animals. Dogs understand us quite well however, and some breeds, particularly once they’ve been trained, can be almost painfully tuned in to the emotional states and the desires of humans.

The third axis is how dangerous they are. What kind of agency does the animal have to inflict harm on human beings? Big predators are obviously capable of killing humans with little difficulty. But it’s not all about fangs and claws. A horse for example can inadvertently maim or kill by smashing a human against a wall or a tree trunk, just because it’s very big and strong. Swarming animals can kill by inflicting small amounts of damage in large numbers.

It hasn’t always been a cakewalk, but we’ve been able to establish a stable position in the ecosystem despite sharing it with all of these different kinds of intelligences. Perhaps this can provide us with a framework for imagining what a future might look like in which we co-exist with AIs. Until now, most people’s interactions with AIs have been through text-based models such as ChatGPT, which are similar to lapdogs in that they are acutely tuned in to humans and basically exist to make life easier for us. Within the last week one such model has come under heavy criticism for being nauseatingly sycophantic towards its users. In my opinion as someone who currently uses various AI-enhanced software packages in an active project, these are the least interesting AIs. More interesting and more important in the long run will be AIs that are like sheepdogs, in that they do useful things for us that we can’t do ourselves. But I think that we’ll also have AIs that are like ravens, in that they are aware of us but basically don’t care about us, and ones like dragonflies that don’t even know we exist. What people worry about is that we’ll somehow end up with AIs that can hurt us, perhaps inadvertently like horses, or deliberately like bears, or without even knowing we exist, like hornets driven by pheromones into a stinging frenzy.

I am hoping that even in the case of such dangerous AIs we can still derive some hope from the natural world, where competition prevents any one species from establishing complete dominance. Even T. Rex had to worry about getting gored in the belly by Triceratops, and probably had to contend with all kinds of parasites, infections, and resource shortages. By training AIs to fight and defeat other AIs we can perhaps preserve a healthy balance in the new ecosystem. If I had time to do it and if I knew more about how AIs work, I’d be putting my energies into building AIs whose sole purpose was to predate upon existing AI models by using every conceivable strategy to feed bogus data into them, interrupt their power supplies, discourage investors, and otherwise interfere with their operations. Not out of malicious intent per se but just from a general belief that everything should have to compete, and that competition within a diverse ecosystem produces a healthier result in the long run than raising a potential superpredator in a hermetically sealed petri dish where its every need is catered to.

That’s probably not a strategy that can be implemented by anyone in this room, however. What are some practical steps that could be taken by policy makers in the near term?

Speaking of the effects of technology on individuals and society as a whole, Marshall McLuhan wrote that every augmentation is also an amputation. I first heard that quote twenty years ago from a computer scientist at Stanford who was addressing a room full of colleagues—all highly educated, technically proficient, motivated experts who well understood the import of McLuhan’s warning and who probably thought about it often, as I have done, whenever they subsequently adopted some new labor-saving technology. Today, quite suddenly, billions of people have access to AI systems that provide augmentations, and inflict amputations, far more substantial than anything McLuhan could have imagined. This is the main thing I worry about currently as far as AI is concerned. I follow conversations among professional educators who all report the same phenomenon, which is that their students use ChatGPT for everything, and in consequence learn nothing. We may end up with at least one generation of people who are like the Eloi in H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine, in that they are mental weaklings utterly dependent on technologies that they don’t understand and that they could never rebuild from scratch were they to break down. Earlier I spoke somewhat derisively of lapdogs. We might ask ourselves who is really the lapdog in a world full of powerful AIs.

To me this seems like a downside of AI that is easy to understand, easy to measure, with immediate effects, that could be counteracted tomorrow through simple interventions such as requiring students to take examinations in supervised classrooms, writing answers out by hand on blank paper. We know this is possible because it’s how all examinations used to be taken. No new technology is required, nothing stands in the way of implementation other than institutional inertia, and, I’m afraid, the unwillingness of parents to see their children seriously challenged. In the scenario I mentioned before, where humans become part of a stable but competitive ecosystem populated by intelligences of various kinds, one thing we humans must do is become fit competitors ourselves. And when the competition is in the realm of intelligence, that means preserving and advancing our own intelligence by holding at arms length seductive augmentations in order to avoid suffering the amputations that are their price.

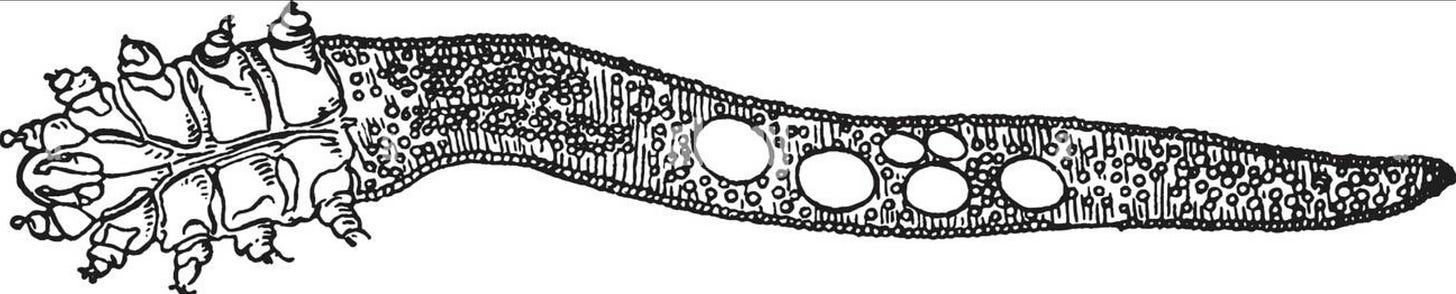

During the panel discussion that followed I don’t think I contributed anything earth-shaking. One remark that seemed to get people’s attention was a little digression into the topic of eyelash mites. You might not be aware of it, but you have little mites living at the base of your eyelashes. They live off of dead skin cells. As such they generally don’t inflict any damage, and might have slightly beneficial effects. Most people don’t even know that they exist—which is part of the point I was trying to make. The mites, for their part, don’t know that humans exist. They just “know” that food, in the form of dead skin, just magically shows up in their environment all the time. All they have to do is eat it and continue living their best lives as eyelash mites. Presumably all of this came about as the end result of millions of years’ natural selection. The ancestors of these eyelash mites must have been independent organisms at some point in the distant past. Now the mites and the humans have found a modus vivendi that works so well for both of them that neither is even aware of the other’s existence. If AIs are all they’re cracked up to be by their most fervent believers, this seems like a possible model for where humans might end up: not just subsisting, but thriving, on byproducts produced and discarded in microscopic quantities as part of the routine operations of infinitely smarter and more powerful AIs.

.png)