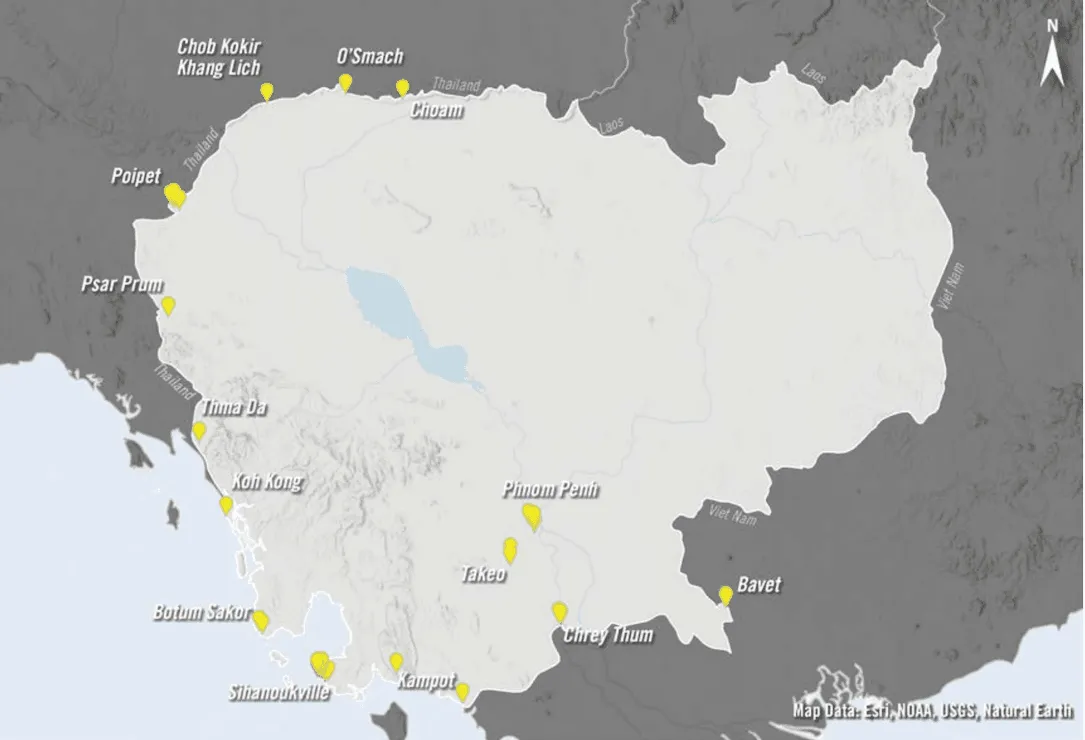

The government of Cambodia’s response to the human rights crisis within the online scamming industry has been “grossly inadequate,” Amnesty International said Thursday, with more than 50 compounds continuing to operate in the country despite purported crackdowns. The international rights watchdog released the results of a nearly two-year study involving interviews with 58 survivors of Cambodia’s scamming compounds and a review of testimony from 365 others trafficked into the industry. The rescued workers were unwittingly ensnared in an industry that has metastasized into a global operation with deep roots in Chinese organized crime. The criminal ecosystem mostly revolves around cryptocurrency investment scams but has evolved to include a range of illicit activities. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, scam centers in Southeast Asia may net around $40 billion annually. The survivors described their experiences of being lured to Cambodia with promises of a job opportunity, only to find themselves trapped in hulking prison-like compounds encircled by razor wire and often with guards carrying electric batons to keep workers in line. Within these compounds the roles for workers varied but coalesced around a single purpose: “to assist in the running of scamming operations.” “In some cases, this meant survivors were given training and a script to directly undertake scamming,” Amnesty International wrote. “In other cases, they were put to work in other jobs at the compound such as administration or food delivery.” Survivors described being photographed and filmed so that their faces could be used to set up bank accounts for money laundering purposes. Some engaged in pig butchering scams — when scammers build up trust through conversations with potential victims before defrauding them — while others described making sham websites to steal information or sell fake products. Locations of the 53 scamming compounds documented by Amnesty International. Amnesty International researchers found 53 compounds in Cambodia where they believe “online scamming or gambling is likely occurring” alongside the trafficking of migrant workers. The organization also identified 45 other “suspicious” locations with security features similar to known scamming compounds, like barbed-wire fencing, security cameras and the presence of guards. The report criticized the efforts of the Cambodian government to curb the industry and in some cases pointed to evidence of potential cooperation between organized criminals and the police. More than one-third of the compounds researchers studied were the site of “interventions” by police or the military, yet abuses continued to occur after visits by authorities, they allege. Another one-third appear to not have been investigated by police despite researchers sharing their findings about them with authorities. Just two of the compounds had been shut down entirely, they wrote. In a letter to Amnesty International, Cambodia’s National Committee to Combat Human Trafficking said from 2024 through early 2025, authorities had received more than 3,500 requests for intervention from “foreigners” involving 6,584 individuals. Just over 3,000 of the foreigners were found, while nearly 800 could not be located. The others “were deemed irregular because they lacked identification for the requester, a specific address, or any contact information for further inquiries.” The agency also claimed to have conducted crackdowns at 28 locations. Such enforcement efforts are being stunted, Amnesty International said, by the fact that the authorities often only rescue specific victims who contact the police or other outside organizations without freeing others who are trapped in a facility. “Even when state-led interventions like police ‘rescues’ took place, they were largely controlled by scamming compound bosses or managers and did not result in the closure of the compound,” they wrote. “In many of the ‘rescues’, instead of entering the compound and investigating, the police would simply meet a boss, manager or security guard at the gate, who would hand them the individual(s) who had requested the rescue.” Survivors told researchers stories that suggested possible collusion between the criminals and police, like being moved to a different facility just before a raid was to take place. After being rescued, they are also often held in immigrant detention centers for weeks at a time in allegedly deplorable conditions and forced to pay for their own meals. In September, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned a tycoon and influential senator within Cambodia’s ruling party for his alleged connections to the industry and to human rights abuses. “Deceived, trafficked and enslaved, the survivors of these scamming compounds describe being trapped in a living nightmare – enlisted in criminal enterprises that are operating with the apparent consent of the Cambodian government,” Amnesty International Secretary General Agnes Callamard said. Cambodia’s endemic scam industry is also stirring up tensions with its neighbors. Amid an escalating border dispute, Thai Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra announced a series of measures purportedly to curb scam operations to the country’s south. “The criminal networks in Myanmar have resettled in Cambodia, so we need tighter measures to prevent Thais being scammed in the future,” Paetongtarn said on Monday. The Thai government banned border crossings to Cambodia across seven provinces and stopped the export of fuel and electricity. The prime minister also announced that authorities would ramp up investigations into “mule” accounts and other financial networks that facilitate transnational crime.

Get more insights with the

Recorded Future

Intelligence Cloud.

No previous article

No new articles

James Reddick

has worked as a journalist around the world, including in Lebanon and in Cambodia, where he was Deputy Managing Editor of The Phnom Penh Post. He is also a radio and podcast producer for outlets like Snap Judgment.

.png)