The Roman Philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca (4 BCE-65 CE) had a remarkable intuition when he noted that “growth is sluggish, but ruin is rapid” (in Latin: ‘incrementa lente exeunt, sed festinantur in damnum’). It describes the behavior of complex systems, and we may even see it as a first description of the modern concept of ‘entropy.’ This post shows how common they are in history, with several ones occurring on and near the Chincha Islands, in Peru

I keep finding cases of “Seneca Collapses” in history. That is, of something that grew slowly up to a certain point, then crashed down. It is typical of the exploitation of non-renewable resources, although it is not limited to that. Here is a new example that I recently discovered: the production of guano in the Peruvian Chincha Islands.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the islands were covered with a layer of some 30 mt of guano, bird droppings that had accumulated over centuries. Around 1840, guano started being dug out and sold as fertilizer worldwide. With its high content of nitrogen, it was a bonanza for agriculture in a world whose population was rapidly expanding.

There are not many images of guano mining in the Chincha Islands in the 19th century. This one shows sacks filled with guano by hand. The structure in the background is probably a crane that carries the sacks to boats moored below. The dreary landscape remains a feature of the islands to this day.

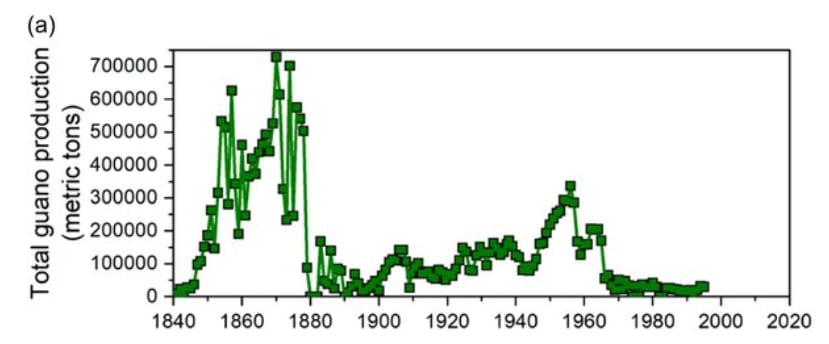

As it always happens with non-renewable resources, growth can’t last forever. The guano was extracted much faster than the birds could regenerate it. The century-old guano deposits were ripped off from the islands, and you see the results in the figure from a recent paper by Riekhof et al.

It is a typical story of overexploitation and collapse: you can see the “Seneca Shape” of the curve that grows relatively slowly up to ca. 1880, then it crashes down.

Remarkably, as described in a 2012 paper by the Mises Institute, the Peruvians of the time understood perfectly well the depletion problem. Unlike most mineral resources, the guano layer was perfectly visible and all located in three small islands; its amount could be easily measured. The engineers of the extraction operation had estimated that the resources wouldn’t allow them more than a few decades of exploitation. And yet, just like in the case of oil and other mineral resources, the guano industry went blithely along the road to the Seneca Cliff by refusing to control and reduce exploitation. Another typical phenomenon in history, it happens when lobbies control the government and fight all attempts to reduce their short-term profits.

In the 1870s, guano production peaked and started declining. The Peruvian economy was heavily dependent on guano revenues, and the Peruvian government worsened the problem by ordering the military to seize the nitrate fields on the border with Chile in an effort to offset the decline. That eventually led to a disastrous war against Chile that started in 1879 and ended with Peru’s defeat. Coupled with “the long depression” that started worldwide in the 1870s, the defeat and the cost of the war bankrupted the Peruvian government and shattered the Peruvian economy which could recover only after several decades. As usual, history rhymes. Just replace “Guano” with “Oil” and we are moving exactly in the same direction, including attempts to seize the remaining resources by military means.

In the 20th century, the Peruvian government attempted to restart guano production and turned the birds of the islands into a state-managed resource. They built walls to protect the islands from wind and eliminated the bird predators. By the mid-1950s, several million birds were counted on the islands. Guano production grew and reached a level of about half that of the golden age of the mid-19th century.

It was another disaster: production soon collapsed, generating a second Seneca Cliff. This crash is normally interpreted as due to the competition with the newly developed Haber-Bosch nitrate factories. That surely had an effect, but it doesn’t completely explain the crash. Guano production required only shovels, and that made it surely cheaper than the nitrates produced by the complex and energy-hungry Haber-Bosch process. As a cheaper fertilizer, guano could have found a niche market. More likely, depletion had played its usual role. With the best of their efforts, the poor birds of the islands couldn’t poop fast enough to keep the production going. It is one of the corollaries of the harsh law of the Seneca Effect: the cliff will be repeated if there is a way to do so.

An image from Google Maps of Isla Norte Chincha. It is the only island that shows modern buildings, a road, and a dock, where ships can probably moor. These structures were probably built in the 1960s and now look mostly abandoned. The land is completely barren and treeless on all the islands.

Today, some guano is still mined in the Chincha Islands, but it is a very small amount. It is reported that a digging campaign is allowed only once every five years, and the last one was in 2024. Nevertheless, with the depletion of fossil resources, fertilizers produced by the Haber Bosch process may soon become too expensive to be used in agriculture. In that case, Guano from the Chincha Islands could again find a market and be subjected to overexploitation. So, we might see a third Seneca Cliff on the islands! Human beings tend to always make the same mistake.

________________________________

The story doesn’t end here: the Chincha Islands are witnessing one more Seneca Cliff: that of the bird population. It is said that at the time of the first guano boom, there were about 40 million birds on the islands. Several million still inhabited the islands during the second boom of the 1950s. The population has now dropped to about 500,000 birds, a loss of some 70% of the population of just a few years ago.

What’s happening to the birds? As usual, when a complex system starts collapsing, several factors collaborate to bring it down. In this case, we have an infection of avian flu, climate factors that disrupted the marine food web, and the overexploitation of the anchoveta fishery by human fishing. The last factor is possibly the most important one, since human beings are removing the main source of food for the birds. The poor creatures are sick and hungry and are dying in large numbers. Another manifestation of the ongoing global ecosystemic collapse.

_____________________________

To finish this post with another Seneca Cliff, let’s look at the fate of the Native Chincha population that lived in the coastal area in front of the islands before the Spanish conquest. Nothing is left of them, except their name. They went through their definitive Seneca Collapse. About the cause of their disappearance, note how Wikipedia describes it,

The Chincha disappeared as a people a few decades after the Spanish conquest of Peru, which began in 1532. Demographers have estimated a 99 percent decline in population in the first 85 years of Spanish rule. They died in large numbers from European diseases and the political chaos which accompanied and followed the Spanish invasion.

It is typical of these reports: they don’t feel happy about writing about how things actually went, and sanitize the story by stating that the Chincha died of “diseases and chaos.” What they call a “decline in population” was, simply, an extermination. The Spanish invaders killed the Chincha people mostly using bullets and lances, in part also helped by diseases and famines. One of the many exterminations that I describe in my book.

____________________________________________________________________________

Note 1: Reikhof et al. model the depletion of Guano using a strange and overcomplicated model they term “to tip or not to tip.” The Seneca model is much simpler and better.

Note 2. If you are Italian, you may have read Emilio Salgari’s novel “La Stella dell’Araucania.” (The Star of Araucania). It takes place mainly in the Southern tip of South America, the Tierra del Fuego. But one memorable scene, which I recall from my childhood when I read the book, takes place at the "guanera del puerto de Stokes," a guano mine where workers labor under grueling conditions, extracting the valuable fertilizer amid the stench and noise of overseers barking orders.

.png)