Skunkworks (n.): an unofficial project developed by a small team working outside the usual rules and red tape

My training was in light combat, my official title was Inventory Clerk, but my actual job was a coder.

In the IDF, draft is compulsory at 18 and ends at 20 for women and 21 for men. Healthy men get sent to combat units by default. If, as a teenager, you have ambitions and you make an effort, you're offered chances to try out for, be interviewed and selected to specialised units, this is true for both combat and non-combat roles.

But this was not me; no ambitions, little effort and definitely not fulfilling my potential in high school, where I excelled only in the subjects that truly interested me. So come the summer of 2005, 18.5 years old, I was drafted by default into anti-aircraft. I call it light combat because it's more intensive than non-combat basic training, but not as intensive as say infantry training. A common question is why anti-aircraft troops need to learn to fight, given they operate behind the lines. The answer is straightforward: in war, your lines might be breached, and your position might come under attack. And that's how I found myself running through the southern Israeli desert, throwing grenades and firing heavy machine guns, playing out every 10 year old’s military fantasy.

I hated every minute of it because I felt so out of place. My heart would sink every time I passed by an on-base IT department, or saw another soldier with the insignia of a well known tech unit. Cursing myself for not making a bigger upfront investment into my future. I knew I'd be a better fit and of better use with a computer. This was totally on me, by the way. I had the opportunity to try out but I didn't really give a fuck at the time and so I effectively jumped head first into the cracks of the system.

After 2 months and towards the end of my training, just as I was about to give up, get with the program and accept my fate for the next 3 years, I was called in to the CO's office where he gave me the news that I'm unfit to operate heavy weapons systems such as in the AA, and that I would be sent back to the drafting base for a new assignment. This, by the way, was also totally on me. I did not make any effort to become a useful and reliable combat soldier.

Think of the drafting base like Amazon's sorting facility, most recruits coming in already have assignments, but when you come in without an assignment, you're basically like an undelivered package. The military is hierarchical. Both in terms of rank, and in terms of prestige. So when you get reassigned, you can only stoop lower in prestige. You would never get re-assigned to something better, more important or more prestigious; only less, because you're an undelivered package. This is how I got re-assigned from the Air Force to the Ordnance Corps.

After arriving at the new base, the corps' training base, weeks were spent just sitting and waiting with a bunch of other randos, until we were to be sorted to our new training and assignments. I finally got to meet with another selection committee that was to decide what my further training and deployment would be. I must've looked and sounded out of place because it seemed like they were surprised to be speaking to me at all. After a few minutes of interviewing the head of the committee said "We might have something for you. We'll call you back. Dismissed". and so I was sent back to purgatory to sit and wait.

Later that evening some guy came to where we were hanging out, and told me he was from a small programming team here on the base. They were a small homegrown team, which normally included 3 people, and I lucked out because I arrived on base just as another member ended his duty. They needed a new team member, and they proposed that I try out for it.

"Do you know how to code?"

"Sure I do!"

Now while I messed around with coding websites, meddling with Javascript and building small apps using Visual Basic 6, I was definitely not on their level. Both of them graduated uni with a CS degree while studying in high school and found themselves in the Ordnance Corps, again through the cracks.

But damn fucking sure I was gonna try out for it, this was the chance I was waiting for.

And so I was brought into their office, shown to a vacant desktop computer, handed a copy of Deitel & Deitel's Java How to Program, and was given a test to build a calculator with Swing GUI.

I was one leg out of purgatory, and while I could spend the day in the office, at the end of day I would have to go back and hang out with the other undelivered packages who were waiting for their assignment. The uncertainty of whether I would be accepted or not killed me.

I must've made a good enough impression because by the end of the week I was accepted to the team! Funnily enough I also got cold feet at that point, doubting whether I really wanted this, or should I seek a different assignment. To this day I don't know why I had this moment of self doubt. I was young, shocked, way out of my comfort zone and cringe as hell. My team-mate, cementing himself as a true romantic (he really is to this day), took me to the canteen, bought me a treat and convinced me to stay.

As it turns out, the team had existed for almost 10 years prior to my coming on the scene. It started out as a project by our then young and intrepid commander, as an effort to computerise the management of soldiers coming through the base, an HR/HCM (Human Capital Management) system if you will. It was one of the largest training bases in the IDF, handling thousands of soldiers a year. Back then, while the army-wide HR was computerised to the point where they had a high level view of each soldier and their assignment, the resolution stopped at that high level. Within the base, tracking a soldier's journey and training was done with either paper, or ad hoc spreadsheets.

Our commander decided to utilise his resources as a head of training development to create a small Excel + Access DB system to help manage soldiers and their training journey in his department. This proved to be a success because that system graduated to be a fully fledged Java application, spreading out through the department, then the branch, to the entire base, to satellite bases and finally to a bunch of major training centres throughout the army. Looking back, he was also one of my first entrepreneur role models. He had a relentless work ethic (first in, last out), held everyone to high standards (quality above all), was extremely professional to brass while hustling and bending the rules to keep us working, and somehow saw potential in misfits like me.

Because this wasn't a sanctioned programming team, there needed to be some way to keep me in the base. In the eyes of the system, I was sent to the base for training and deployment, not to hang around. I'm not quite sure how, but our commander, ever the champion hustler, made an arrangement that team members would undergo a short and arbitrary Ordnance training, and be kept on base under the guise of that job. My training was to be an inventory clerk. It was quite surreal to go from basic combat training, waiting, programming for a month, train as an inventory clerk, then go back to programming. But if that's what kept me there, so be it.

And so we had to be scrappy, make do with what resources we could get our hands on and hustle favours from IT departments and the official tech branches. Existence was weird. Our colleagues were commanders and guides that went through cohort after cohort of trainees, using our software everyday, and we existed in between that. The bunch of nerds that shouldn't be there but somehow were.

"Why didn't you give us a heads up?" they shouted over the phone, "We're drowning in support tickets!".

When I joined the team, we were using Java 1.4, and the application was served by us, hosting an instance of the server in the IT server room.

Endpoints that needed access to our system had the Java client app installed on the desktop, and the client app spoke to our server using RMI (Remote Method Invocation), Java’s way of making calls between 2 applications over the network.

While this setup is pretty straightforward, we couldn't expect the layperson to be able to perform net new installations and version updates on their own; i.e., going to a destination site, downloading a jar file, saving it somewhere, creating a shortcut that executes that jar file using the local Java runtime, etc. So every one of those cases required a ticket and the attention of the IT department, which for the users, was a pain.

They'd call us on the phone to report a bug, then we'd be like "yeah, we fixed this with the update last week. You gotta upgrade"; our permissions were limited and so we couldn't help them do it, so we had to redirect them to the IT department where hopefully, the new version would sort the bug out. What should've been a simple version update, became an issue for a couple of hours, and work would be blocked.

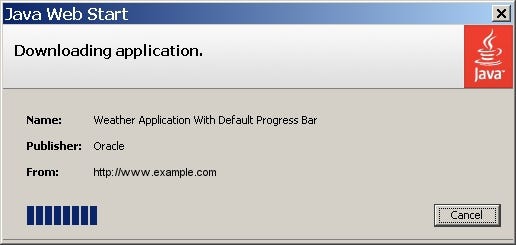

I figured out that there surely must be a better way to provision and update so I made my way to the IT department office, who had the only internet connected terminal on base, and after some googling I discovered the wonderful features known as Java Web Start and the Java Network Launch Protocol, which turned out to be exactly what we needed. Instead of installing via all the manual steps described above, the user would go to the internal destination site, the destination site would redirect them to the JNLP file which was a manifest that described what files the application needs, where to get them, and how to install them. The JNLP also had its own mime type, which meant that when the user downloads and opens the file, it would trigger an installation wizard using the local Java runtime; this process would automate the download and installation of the application. The cherry on top was that it was also able to automatically manage updates. So whenever a new version was published, it would automatically be downloaded the next time the user opened the app. Magic a-la 2005!

I looked up what changes we had to make and all we needed to do was just upgrade from Java 1.4, to Java 1.5. Oops. Do we even have Java 1.5? Did IT HQ approve it and distribute it? After some digging around on the intranet I found out that, yes! fistbump. Java 1.5 is available. I grabbed it off the intranet, ran tests, simulated different scenarios and by the end of the week, the feature was ready. I couldn't wait to ship it.

We normally spent the entire week at the base, and visited home on the weekends, so we arrived on base by 9 on a Sunday and left for home by 4 on a Thursday. At first I didn't understand why and I hated it (boring, I miss my gaming desktop), but after an adjustment period I grew to appreciate it for what it could give like camaraderie, responsibility, independence and more time to focus on work. This environment also taught us to work better as a team on a shared mission, mentoring new programmers who joined us, and building friendships beyond the daily work, which in turn made it more bearable. Come to think of it, it felt almost like founders who live and work out of the same flat.

Being my enthusiastic self I was sometimes so caught up with the work that I would occasionally cut my leave short and return to base on Saturday evening so that I could get some focused work done.

And so it was on that Saturday that I decided to come back to base and deploy the new version. I was truly excited for this major improvement.

Come Sunday morning, there's no joy and gratitude, just chaos. Staff have arrived on base for a new work week, tried to open up our application but couldn't. “What the fuck is this thing about a JNLP file?” Users were exclaiming.

Turns out Java 1.5 was not widely distributed and was not in our IT department's endpoint installation image. No one could work. The phone was constantly ringing, and again I had to redirect the users to the IT department, because only they had the permissions to install the new version of Java, and everyone on base needed this to happen right now.

As it turns out, the update I shipped kept almost the entire IT department busy for the whole day, leaving no resources for any other issues. Luckily the memory of this stunt didn't last too long, and the update did in fact reduce overall the number of tickets just by eliminating installation and updates.

During our service, the bubble would occasionally burst and we would get a surreal reminder that we are still in the army. For example, we would periodically be sent into full-time guard duty for a set period of time. It would range from a 24 hour duty in our own base, to a full week in a totally different base.

It's very strange to be plucked out of your team and your routine, to a temporary rag tag team of strangers.

Imagine you’re a Google SWE, crushing it in the Mountain View campus, then one Monday morning your boss pops by and says “Yo, Dave. One of the guards in the Ohio data centre is out sick. You’re up!”, and so you pack your shit and off to Ohio you go.

For a person like myself who always has to be doing something, guard duty is torture. You guard for 4 hours and during that time you aren’t allowed to do anything else. You can then rest for the next 8 hours but there's nothing else to do.

This one time I got sent to guard a hill inside an Ordnance testing facility on the shore. We were dumped into a caravan in the middle of the dunes overlooking the sea. Around us was nothing but sand, the watchtower and a few old garages. Just me, a car mechanic and a warehouse inventory clerk. Supplies would be brought to us once a day and patrols would check in with us every now and then to make sure we didn’t go AWOL and/or insane.

A couple of weeks prior to being sent on duty I bought (not pirated) O’Reilly’s Head First Servlets & JSP, and decided to bring it with me to help pass the time. This coupled with a book about the networking stack quickly earned me the nickname "The professor" from my new mates.

Days passed by slowly. In the distance you could hear screams from an amusement park on the outskirts of the most nearby city. An occasional shell would be fired out onto the sea. I carve my girlfriend's and my name = ❤️ into the tower wall. A chopper passes by and does target practice on a truck.

And just like that it was over. Back to the office, back to Java, back to my real job that didn’t exist.

I had an assignment to add more email capabilities to our Java app. The military used Microsoft AD for identity and Exchange for email. In these days connecting Java to Exchange could be done using some core libraries or a special Win32 DLL, but that only gave capabilities to send emails, not handle receiving emails. My task was to find a way to receive them.

I found on the internet this niche proprietary library which promised to do that, and it cost something like $100. Being a poor 19 year old in a skunkworks unit I did not have that kind of money, nor could I expense it (we didn't exist), so what would any enthusiastic Millennial do? Pirate of course! But bringing in outside material into the military network was not straightforward.

The army obviously has strict rules about information security, but you know what it's like, individuals with enough curiosity and motivation will always find a way. It was a period when rules were strict but not all that strict as the internet and mobile phones were only starting to bring in their changes. InfoSec HQ was reducing risk by hardening all endpoints using automatic Windows scripts, disabling external storage media, auto-installing anti-virus and so on. Not only were the computers hardened but they were also set up to alert on any operation like inserting a USB key, or trying to tamper with the hardening. So even inserting a CD-ROM would get you InfoSec-fucked.

Obviously people had the need for inserting material from the outside world, just like we did, and so you had special IT departments spread out across the country, which would have a procedure for taking your material, filtering it through different checks, and if it was clean, they'd allow you to insert it into the network and email it to you. And it was a pain in the ass. You had to make an appointment with them, then you'd have to take a bus (or ask your commander for a favour and have him drive you with a military vehicle), hope the person on the station wasn't on leave or out on a long lunch, then hang around for a few hours while they work and hope they don't miss any files. Even more so a pain in the ass for a team that wanted and needed to be agile, move fast and keep up to date with the latest developments.

And so through the different generations of our team (because a person's service lasts 3 years and by my joining the team already existed for technically 3 generations), we had built up an intimate relationship with the on-base IT team. Many times they would turn a blind eye to our hijinks. One of the people on the onsite IT team was this guy Yuri who was a computer whiz kid, at age 19, already with a CS degree and an industry job under his belt. He was totally wasted on the mundane IT job he was assigned. He could have easily joined a prestigious computing unit, but declined as most of them compel you to serve for longer in exchange for the specialisation. But Yuri wanted to be done as soon as possible, so that's how he became a plain old IT dude and he didn't give a fuck.

Anyway, he developed a set of Windows registry tweaks that removed all of InfoSec's scripts and limitations, effectively un-hardening the endpoint. Given our special relationship, we managed to squabble from Yuri an unhardened endpoint we kept secret in the office. Whenever we wanted to insert external material needed for work (books, new software libraries), and couldn't be arsed to make the pilgrimage to InfoSec mecca, we would thoroughly scan the material using an antivirus, insert it into the unhardened computer, connect the computer to the network so that we can transfer the files to the NFS, and then disconnect the endpoint again. Voila, you've got the latest version of a logging library.

This time I was careless and I fucked up. As I inserted my pirated Exchange integration library to the endpoint, the antivirus immediately popped up. I quickly disconnected it from the internet, removed the file and hoped that I was quick enough. My heart was racing. I was sure I was gonna get a phone call the next morning. Being careless and 19 also meant I was more worried about myself than about compromising InfoSec.

The next morning came and there was nothing. And the next, and the next. And after about a week I thought that I was in the clear and sort of forgotten about it.

About a month after the incident I got called in to the IT office, and there on the table was a report from InfoSec HQ with my stupid mug on it. This is also when I had to come clean to my commander, who lucky for me gave me his full support.

I was brought to a military tribunal and faced a prison sentence. Due to my track record and my commander’s support, I was shown leniency, and was instead sentenced to a year on parole. That meant I could get sent to prison for absolutely anything. Even if military police catch me jay walking, or not having the right pass for leave.

But worse than that, it tainted our relationship with the IT team. It raised many questions such as where did we get this endpoint, how was the hardening removed, and they were forced to open an internal inquiry. We lost their trust. They remained helpful and friendly, but were no longer willing to bend the rules for us.

This is the point where I would say that from there on I watched every step. But that would be a lie.

Also, I never managed to get the email receiving feature to work.

I consider this my first startup experience. Our CO was an incredible leader/hustler/product person. He kept us on a tight leash, a tight schedule, but gave us freedom of movement and whatever support & resources he could. He encouraged us to push boundaries, maintain a high standard and think of the customer.

On the other end, the team had its own ethos (lore of previous generations and their escapades), mutual high standard expectations of professionalism and accountability.

I believe that this planted the startup bug in my brain. It's the only way I wanted to work. And it was right after being discharged from the army, that I got the opportunity to join JFrog as a founding engineer. An experience that would also prove to be immensely valuable and maybe fit for another post.

Looking back I am truly grateful for this opportunity and experience, given the circumstances.

.png)