🎮Game ♟️Strategy 🏁Chess 🤖Algorithm 💻Game Dev

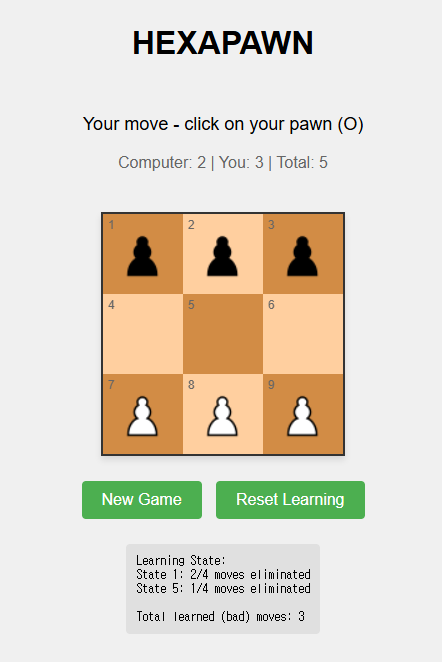

Want to try the game first? Play the JavaScript version here. Source code available here.

From my teenage years until now, I’ve kept an old BASIC book. It’s a translated version of “BASIC Computer Games” written by David H. Ahl. BASIC (Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) is an old programming language designed to be easy for beginners to use. It was probably easier to use than assembler or C. I remember later creating a text-based game where seven countries fought each other in turn-based combat. It was my first game that I was quite proud of, but I’ve since lost the source code.

The reason this is labeled as Volume 1 is that it doesn’t include all the games from the original that I recently looked up out of nostalgia. Perhaps the editorial team omitted some games during the translation into my native language. No Yahtzee! However, they seem to have faithfully transcribed the source code without typos. Since someone has uploaded these to GitHub, I was saved the trouble of retyping the source code for this review.

Opening this book brought back an old mystery from the depths of my memory. It was the source code for a game called Hexapawn. While other programs were difficult enough for me to understand, this one was particularly challenging.

Let’s first understand what this game is about. It’s a type of minichess. Minichess is a chess variant played on a board smaller than the standard 8x8 chessboard, usually with fewer pieces. The game becomes simpler and more concise than regular chess, and is often used for educational purposes or as a proof of concept. I recently created a minichess game with three different game modes.

As the name suggests, this game features 6 pawns, with two players each having 3. The goal is to either eliminate all of the opponent’s pieces or reach the end of the board (the opponent’s starting line) before they do.

The complete source code for Hexapawn from BASIC Computer Games can be found here. In this blog post, I won’t review the entire code, but will focus on the parts that interest me.

DATA - Board, Actions

The most difficult part of the source code was lines 900 through 970:

The DATA command appears, followed by a series of meaningless numbers. -1, 0, 1 appear, then suddenly two-digit numbers appear with 0s, and it abruptly ends. It feels like listening to Radiohead’s music after their 4th album, which I still can’t follow. Can you understand the frustration I felt as a child trying to understand this source code?

So what is this source code? And what is DATA? When I asked my friend Claude.ai, I got the answer.

First, unlike modern programming languages, BASIC requires you to write line numbers directly for each line, followed by a space before the actual command. Line numbers don’t have to be sequential, but they’re usually arranged in ascending order. This is because readability makes maintenance and reuse more convenient. When I learned it in the old days, I used line numbers in increments of 10 like 10, 20, 30. This was because you might need to insert other line numbers like 15 in between.

For example, a BASIC code that receives a value A and immediately prints it would look like this:

In BASIC syntax, DATA is a command that pre-stores constant values to be used during program execution. During execution, these data can be read sequentially through the READ command.

READ searches for DATA globally. It reads from top to bottom and reads the first values it encounters. While modern languages like JavaScript and C prefer to define variables first before using them, BASIC was designed for learning and emphasized simplicity and implicit operations. Even if a student learning programming forgets to define DATA at the beginning and defines it later, they can still read the first values encountered with READ. Therefore, the above program outputs 100, 200.

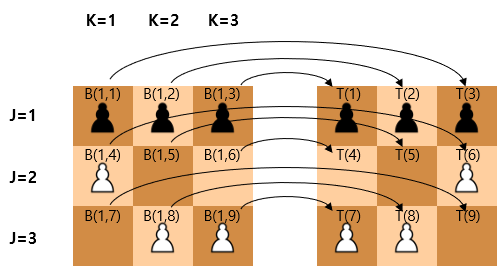

The code stores the board in B as a two-dimensional array:

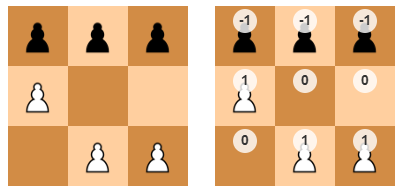

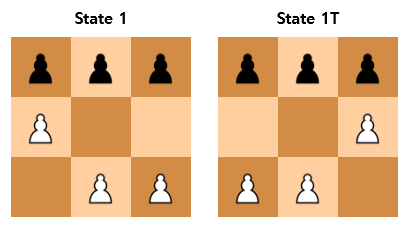

The 19 possible game states stored in lines 900-945 are saved in B(1,1) through B(19,9). For example, line 900 contains 2 game boards, and the first 9 numbers -1,-1,-1,1,0,0,0,1,1 are stored as B(1,1) through B(1,9), which can be represented on a 3x3 board as follows:

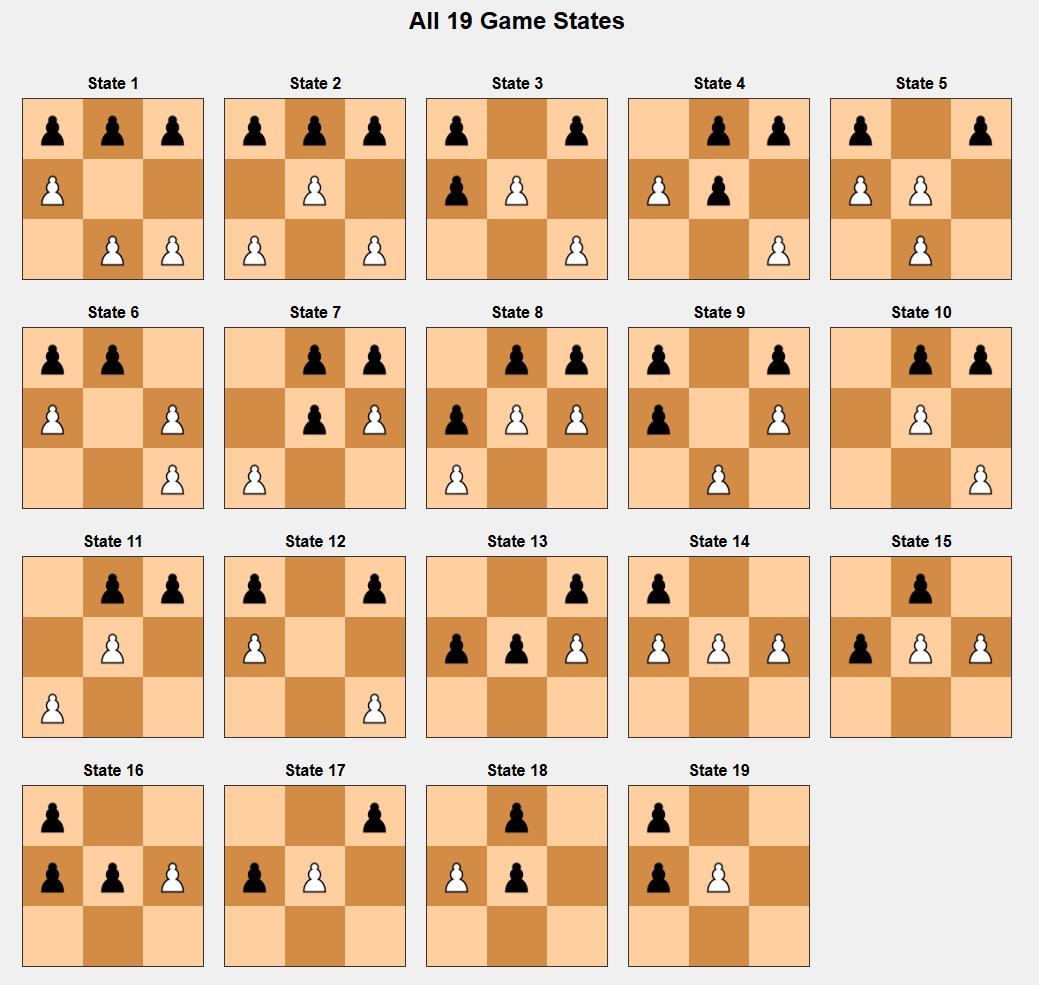

When all the data from lines 900-945 are represented as boards:

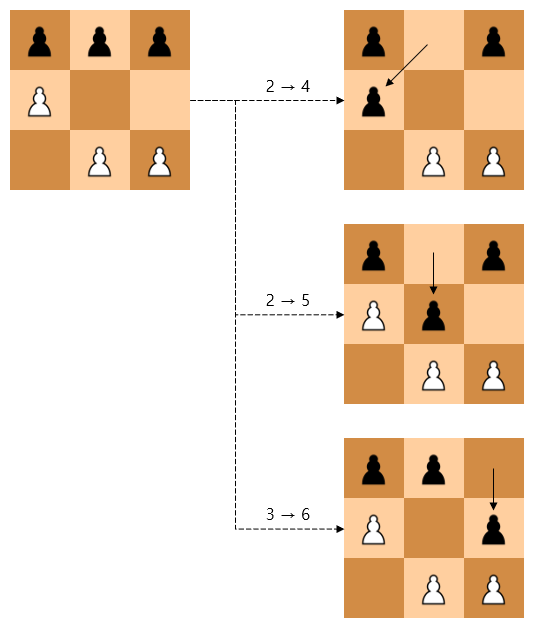

Now let’s see what lines 950-970 mean. These are about state transitions. Each square on the 3x3 board can be represented as 1-9 from top to bottom.

This defines the actions the computer can take. For example, state 1 is -1,-1,-1,1,0,0,0,1,1 as shown above, where the computer (black) can move pawns at positions 2 and 3. Pawn 2 can capture the white pawn at position 4 or move to position 5, and pawn 3 can move to position 6. Since there are no other actions, the remaining action slots (up to 4 maximum) are filled with 0. This is represented by the first four numbers in line 950: 24,25,36,0.

Did you notice that the states shown here are not in lines 900-945? The computer doesn’t need to have these states. For states resulting from the computer’s actions, the human will respond with some action, and the computer only needs to have the results - that is, the states the computer can face. The states the computer can encounter on its turn are only the 19 states in lines 900-945.

However, horizontally flipped states are not stored here. For example, State 1T, which is the flip of State 1, is not included. But since these states can naturally occur in the game, the code directly flips them horizontally using an array called T to find them.

The code stores actions in M as a two-dimensional array like B:

Board Matching

Now we need to match these defined boards with the current game board state. After all, we need to select one of the predetermined actions. The code for matching boards is here. Since there’s a triple FOR loop, I’ve added indentation not present in the original to aid understanding:

Here, I loops through the 19 states in the outermost loop. In the first inner FOR loop, the original board array B(I,1~9) is horizontally flipped and stored in T(1~9). J is the row and K is the column.

The second inner FOR loop checks if all values of the current game state S and the board B being traversed are the same. <> is the not-equal operator, which can still be found in Excel, VBA, and SQL today. If all 9 values of S and B are the same, it sets R=0 and sends program execution to line 540 using the GOTO statement. The GOTO statement was commonly used in programming languages in the past, and here it’s used to exit the entire loop immediately without going through the next loop after the inner loop ends. In modern languages, something like a break statement would be similar.

If a difference is found between the current game state S and the board B being traversed, it moves to line 460 to execute the third inner loop. Here it checks if all values of the current game state S and the flipped board T are the same. If all 9 values are the same, this time it sets R=1 and also goes to line 540. Here R is a switch for whether it’s a horizontally flipped board, and when selecting an action, if R is 1, it performs an action appropriate for the flipped board.

As an aside, line 511 is entered when it fails to find matching values with the current game state for all 19 boards and flipped boards. It seems like it was originally intended to be a comment using the REM command like 511 REM REMEMBER THE TERMINATION OF THIS LOOP IS IMPOSSIBLE, but perhaps that part was omitted during editing, so it just starts with REMEMBER.

Action Selection

Now when we get to line 540, the index of the selected board is stored in X, I is used again as a FOR loop index, and it looks for non-zero values among the possible actions M(X). Non-zero values are possible actions, so if it finds such a value, it goes to line 600 and exits the loop. If it can’t exit the loop, meaning all values are 0, the AI has no moves to make and resigns.

In lines 600 and 601, the AI uses the RND() function to return a random value between 0 and 1, multiplies it by 4, adds 1, and converts it to an integer to store one of the values 1, 2, 3, 4 in Y. This is repeated until the action value M(X,Y) is not 0.

Line 610 sends to line 630 if R=1 (flipped board), otherwise it performs the move in lines 620, 622, 623. Here the FNM function is probably an abbreviation for FuNction Modulo. The FNM function appears in line 30 and extracts only the ones digit from a two-digit number through modulo 10 operation. And INT(M(X,Y)/10) extracts the tens digit, so we can see it defines the starting and ending points of the action.

In the current game state S, the value at the pawn’s starting point is changed to 0, and the value at the destination is changed to -1 so that a black pawn arrives at the destination regardless of what’s there. If there’s a white pawn there, it will be captured in this process.

After the move is complete, it goes to line 640 and uses GOSUB to go to line 1000. Unlike GOTO, GOSUB can return to the line after the original position using RETURN. The code starting at line 1000 outputs the current game state.

Actions on a flipped board are a bit more complex, using a function called FNR and the FNS function it calls. These are probably abbreviations for FuNction Reverse and FuNction Same.

To understand this code, you need to know what values BASIC calculates for true and false in conditional expressions. In modern programming languages like Python, C, and JavaScript, True is usually 1 and False is 0. But in BASIC, True is -1 and False is 0 (I’ll skip the detailed explanation for this as it seems beyond the scope of this blog).

Knowing this, if we think about the calculated value of -3*(X=1), when X=1 it’s True so it becomes 3, and when X=0 it’s False so it becomes 0. In the same way, we can see that 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9 all maintain their values only when they’re equal, and become 0 when different.

So what is FNS? As the name suggests, it preserves the same value when it comes in. When X is one of 2, 5, or 8, it satisfies (X=2 OR X=5 OR X=8) so this entire value becomes True, i.e., -1, and when multiplied by -X, 2, 5, 8 come out as they are.

In summary, the code from lines 630 to 633 performs the action on the original board with flipped values for the starting and ending points. That is, if it’s 2->4, it becomes 2->6.

Learning

The explanation at the beginning of this book’s source code says this. I remember not believing this when I saw it as a child. Is that possible with such short code?

As the game progresses, the computer improves its weaknesses and learns tricks…. If the computer loses a game, that method is eliminated.

But in conclusion, it is possible.

What the source code initially provides is all possible actions from all states. Summarizing the above, the AI selects a random action among them. Such an AI doesn’t seem like it would be strong.

As a result of the game, the AI can win or lose. If a human reaches the top row, the human wins, and conversely, if the computer reaches the bottom row, the computer wins.

When the computer wins - that is, at line 870, it doesn’t take any special action other than increasing W, which represents the number of wins, but at line 830 following line 820, it erases the action. The action erased here is the action the AI just performed. In other words, it deletes the last action that was the direct cause of the behavior leading to defeat.

This is the secret of AI learning. The AI gets stronger and stronger. So how strong does it get? According to Martin Gardner, who first proposed this game, it plays perfectly after losing 11 out of 36 games. In fact, this is a solved game where black, who moves later, always wins, and if both play perfectly, black always wins in 3 moves. In the original article, Martin Gardner said that this method would be possible for mini-checkers with 2 checker pieces each on a 4x4 board, but minichess would be too complex to be possible. In fact, Martin Gardner introduced Donald Michie’s MENACE (Matchbox Educable Noughts And Crosses Engine) as the origin of Matchbox learning machines. Created in 1960, MENACE was a machine that learned tic-tac-toe with 304 matchboxes.

MENACE’s operating principle is similar to HEXAPAWN:

- Each matchbox represents one game state.

- Inside the matchboxes are colored beads, and each color represents a possible move.

- If you win the game, you add more beads of the same color used, and if you lose, you remove them.

- Over time, beads for good moves increase and beads for bad moves disappear.

Interestingly, MENACE hardly loses after about 80 games, and even ‘learns’ to exploit human mistakes. This shows that the core principles of reinforcement learning can be implemented with just simple beads and matchboxes.

While HEXAPAWN is sufficient with 19 states, tic-tac-toe requires 304 matchboxes because there are more unique states even considering the game’s symmetry. Nevertheless, the fact that both can be implemented with physical boxes stands in stark contrast to today’s neural networks with billions of parameters.

These early experiments played an important role in introducing the concept of “learning machines” to the general public and can be seen as laying the philosophical foundation for modern AI.

Now let’s actually play this game. I’ve implemented this game in JavaScript here. The source code is available here, so feel free to use it. You can actually see that once the AI learns about 7-8 wrong moves, it hardly loses.

So far, I’ve solved an old mystery that has been bothering me in a corner of my mind since childhood. While adding comments and explanations to the code, I briefly thought, “If someone had taught me this back then, couldn’t I have done more things faster?” Anyway, thank you for following me on this long journey, and I’ll continue to strive to write good articles.

.png)