In 1985, a small team of Sony engineers came together to launch one of the most daring and unconventional chapters in the company’s computing history. It had nothing to do with music, movies, or gaming at the time. But the decisions made during this quiet internal effort would ripple through Sony’s future, shaping the mindset, architecture, and engineering approach that would eventually help make the PlayStation possible.

In the early 1980s, Japan was investing heavily in its technological future through a series of national initiatives designed to advance computing. The most ambitious of these was the Fifth Generation Computer Systems (FGCS) project, which aimed to develop machines using parallel processing and logic programming to support scientific research and industrial innovation. Major players like Fujitsu, NEC, and Hitachi aligned themselves closely with this government-backed vision. Sony, however, stood somewhat apart. Unlike those companies, which had deep roots in computing and enterprise systems, Sony was still primarily known for consumer electronics. It had begun exploring computing through ventures like the SMC-70 and SMC-777, which introduced the 3.5 inch floppy disk and targeted both business and hobbyist users, but these efforts failed to make a significant impact in the computing space. The company had also joined the MSX consortium, a standard for home computers, which found success in Japan and parts of Europe but never positioned Sony as a computing powerhouse.

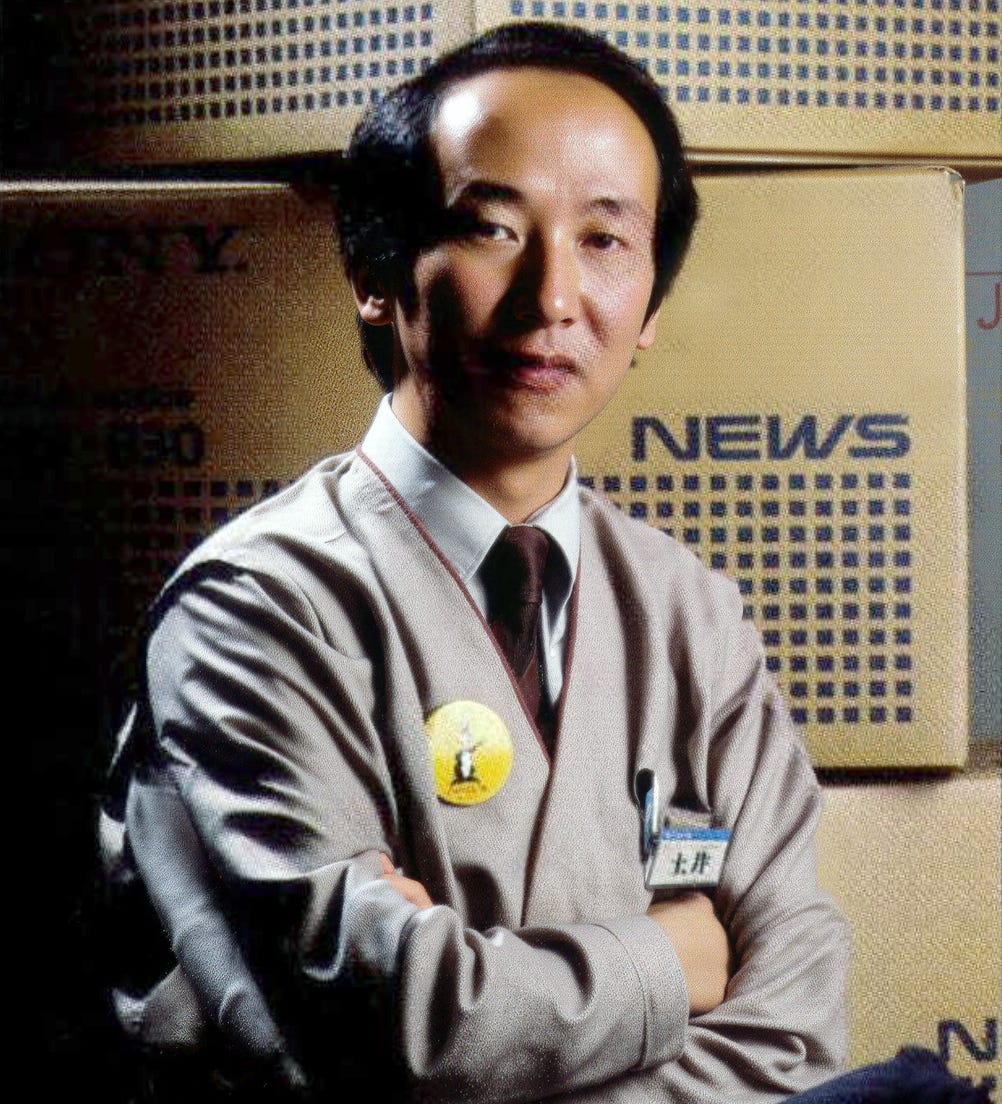

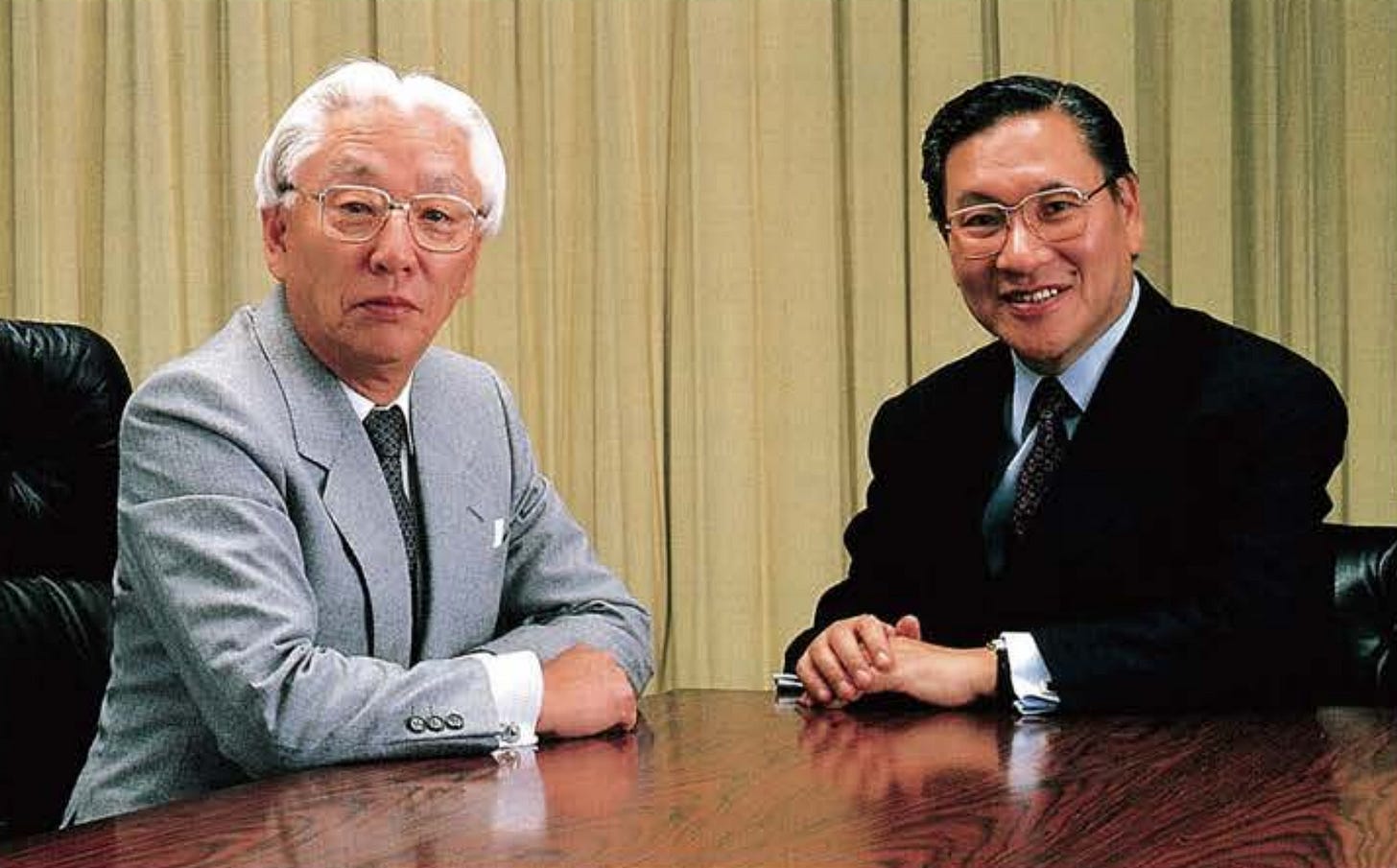

One engineer inside Sony believed it could be more. Tadashi Doi had already helped pioneer Pulse Code Modulation, the foundation for digital audio recording, and co-developed the Compact Disc. He knew firsthand the kind of tools engineers needed. He envisioned a powerful UNIX based machine that Japanese developers could actually use, one that could rival offerings from Sun and DEC, but with Sony’s design DNA. Sony had already made several attempts to enter the computer market but had struggled to gain meaningful ground. Internally, many still viewed computing as a sideline at best and an unprofitable distraction at worst. But Doi was undeterred. When his proposal was shot down by senior management, he bypassed the chain of command and went directly to then president Norio Ohga. To his surprise, Ohga approved the plan on one condition: the project would be treated as a self contained internal venture, separate from Sony’s core operations.

Akio Morita, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer (left), and Norio Ohga, President and Chief Operating Officer.

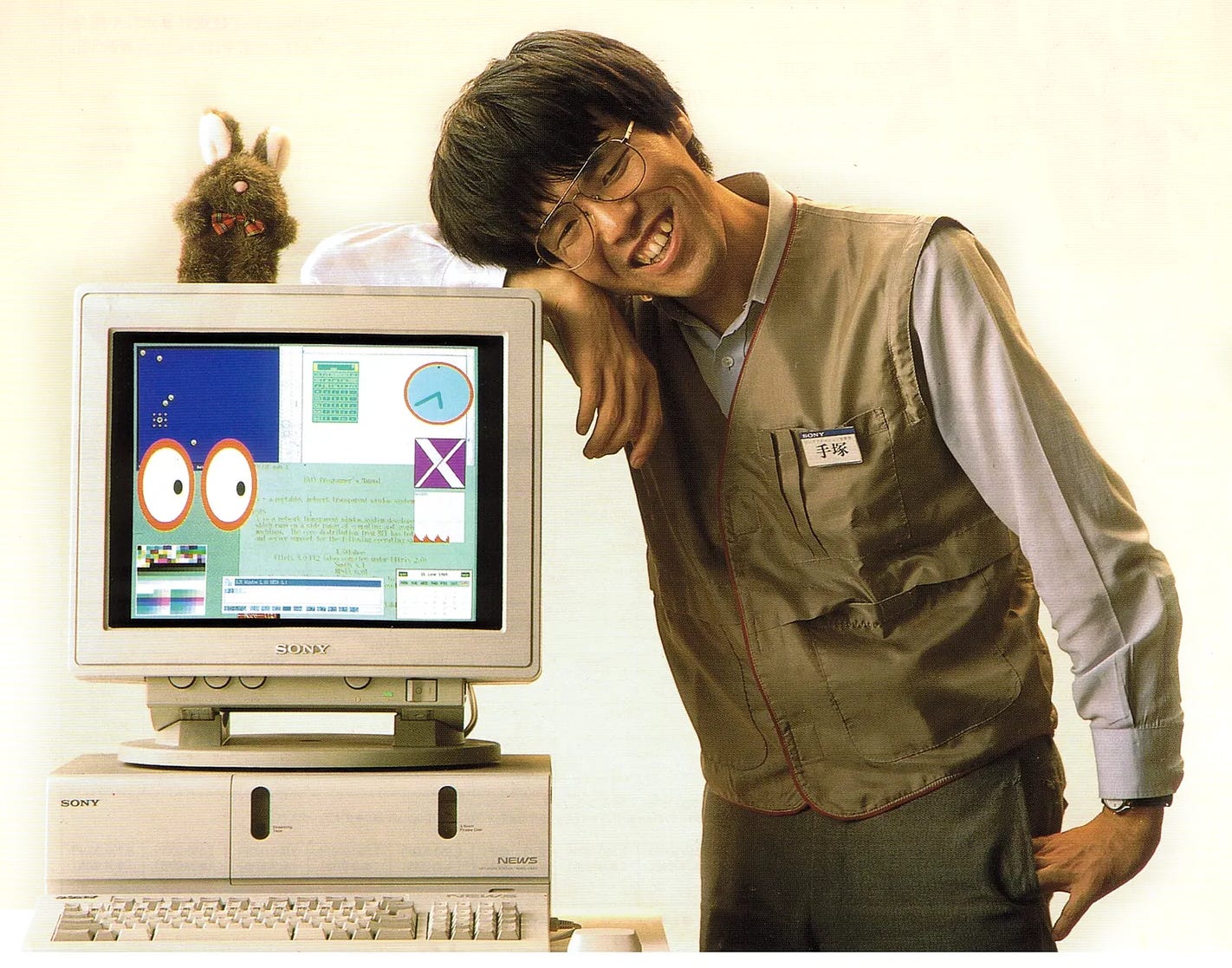

With the green light, Doi assembled a group of 11 engineers, four from his MIPS division and seven from Sony’s Development Institute. The team started work in September 1985 under the internal code name “ICKI” (イッキ). Whether a play on the Japanese word for uprising or simply a catchy label, it captured the team’s determination to break from convention. Their goal was to create the kind of machine they wished they had themselves: smart, open, powerful, and untethered to legacy systems. It was, in a way, a computer built by engineers for engineers.

Initially, Doi had imagined a continuation of Sony’s efforts in office automation (OA), particularly building on the legacy of the SMC-70, a business oriented computer introduced years before. But the team had other ideas. They wanted to build a UNIX workstation that could replace the DEC VAX systems they relied on daily. These were room sized computers developed by Digital Equipment Corporation, commonly used in universities and research labs throughout the 1980s. The engineers envisioned something more scalable and affordable, a machine that could deliver similar performance on a developer’s own desk. Doi quickly recognized the opportunity. If Sony could produce a high performance workstation at a fraction of the usual cost, it would not only be a great tool for engineers but might open up an entirely new market for the company.

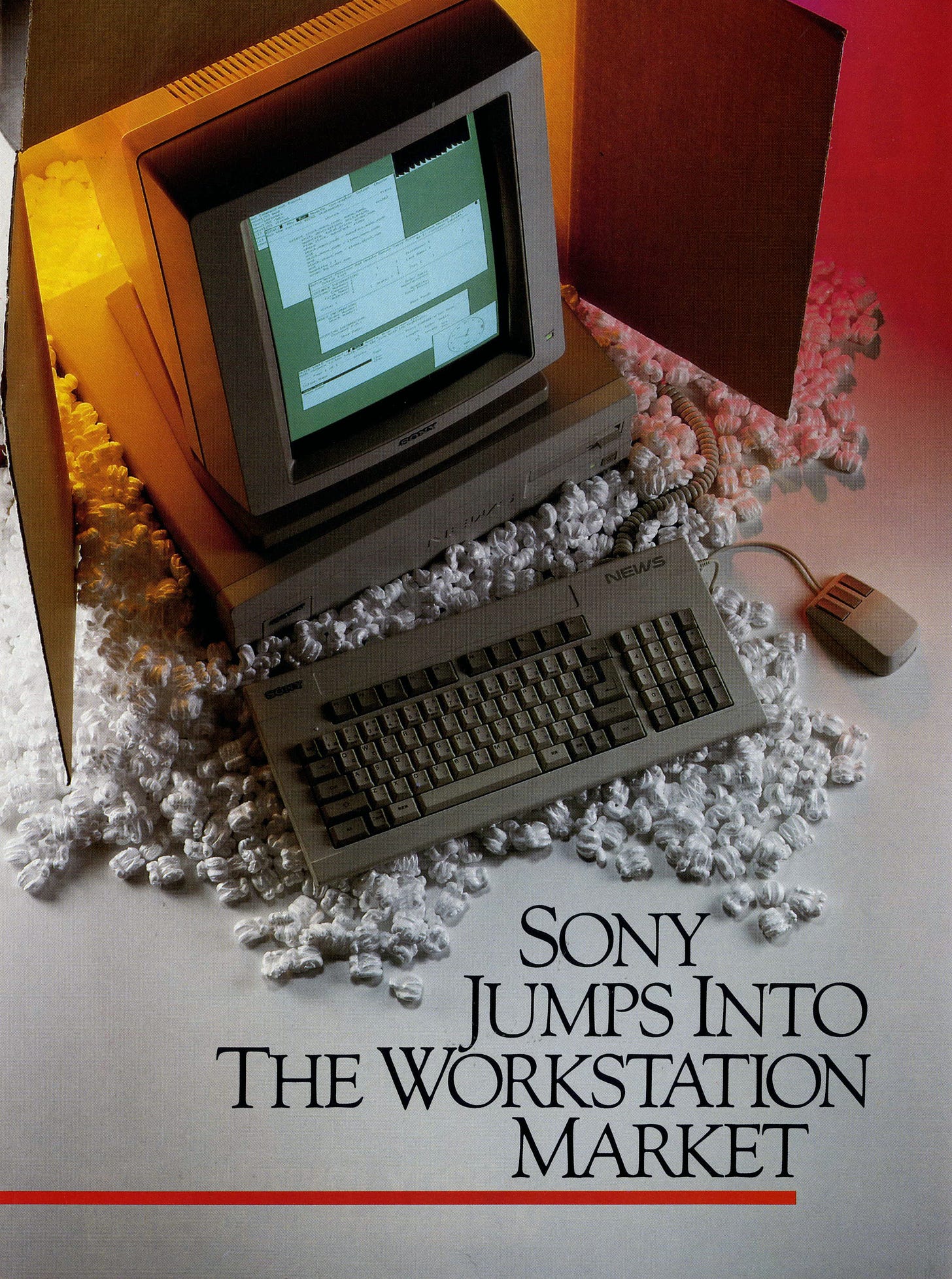

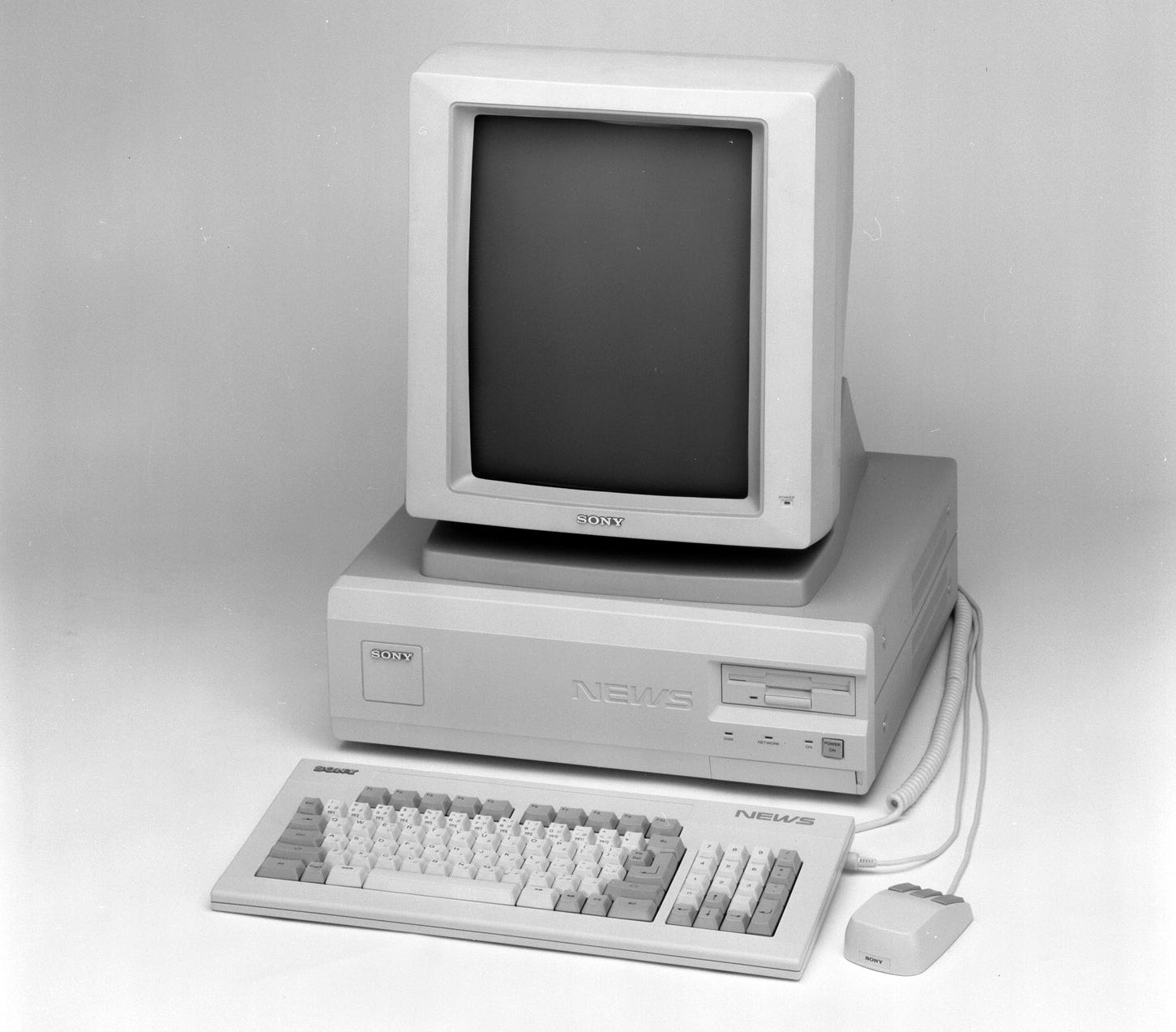

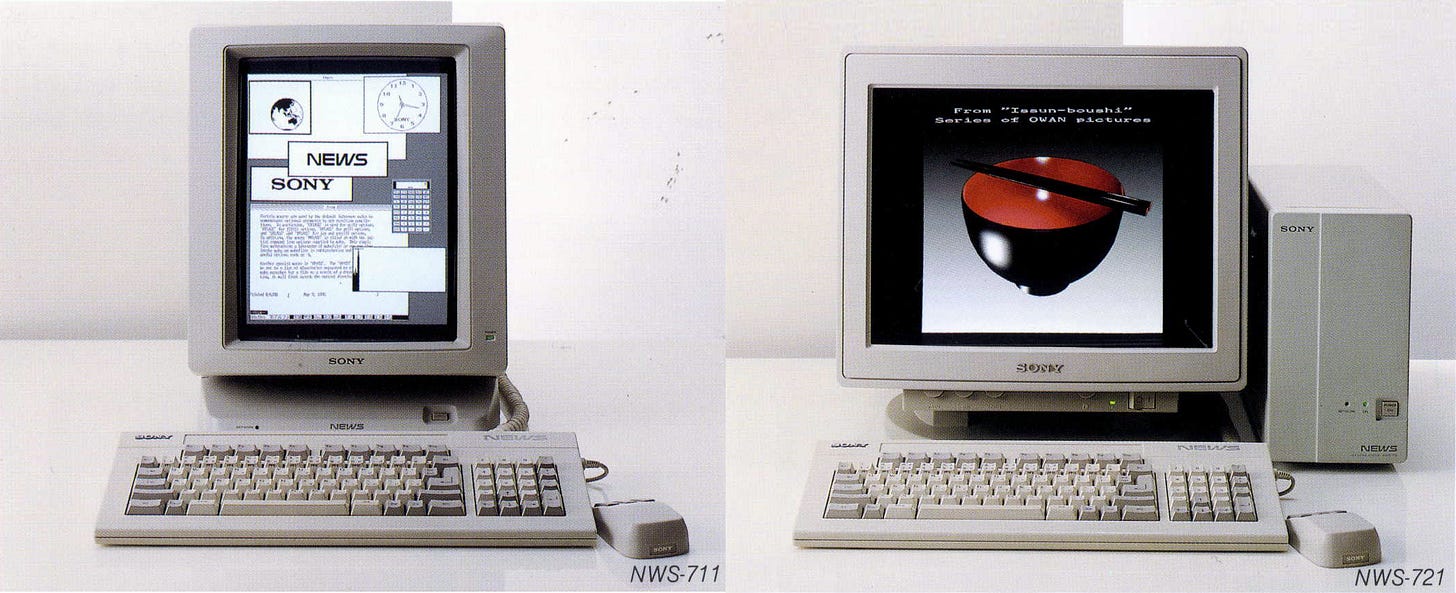

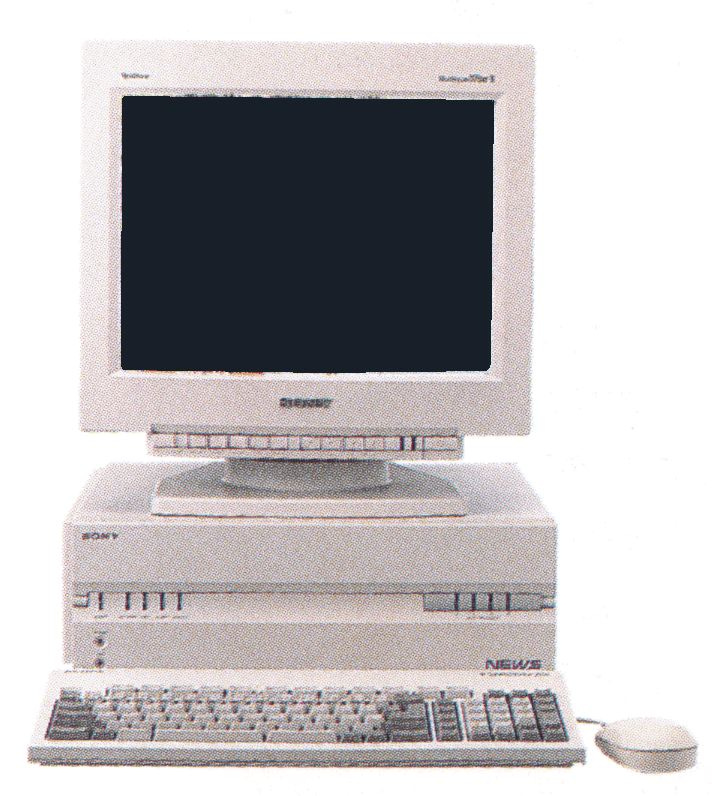

The first prototype was ready in just six months. By October 1986, the project was announced, and in January 1987, the first NEWS workstation, the NWS 800 series, officially launched. It ran 4.2BSD UNIX and featured a Motorola 68020 CPU. Its performance rivaled that of traditional super minicomputers, but with a dramatically lower price point ranging from ¥950,000 to ¥2.75 million (approximately $6,555 to $18,975 USD in 1987). Competing UNIX workstations typically cost closer to ¥10 million (around $69,000 USD). NEWS caught on quickly in universities and R&D labs, where cost sensitive researchers needed real performance. The venture team had invested ¥400 million into development (about $2.76 million USD), and remarkably, they recouped those costs within just two months of launch.

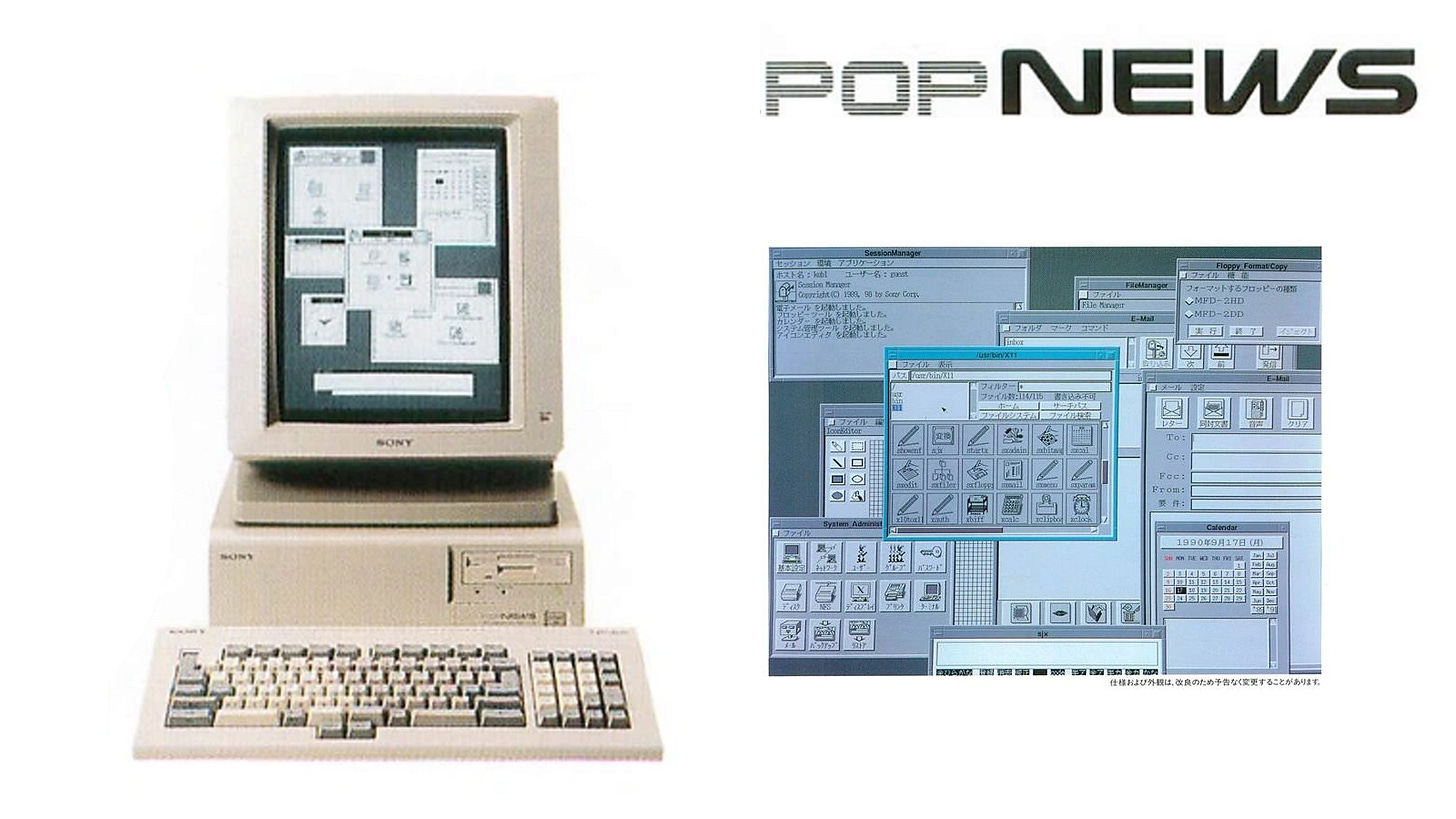

That same year, Sony introduced a lower cost version called POP NEWS (PWS 1550). With a GUI shell named NEWS Desk, a document sharing format called CDFF (Common Document File Format), and a focus on Japanese language desktop publishing, PopNEWS aimed to make UNIX more accessible to general business users. Targeted at the Desktop Publishing market, it showed Sony’s desire to bridge consumer and professional segments in ways no other UNIX vendor was trying at the time.

In 1988, Sony upgraded to the NWS 1850, which used the Motorola 68030 processor running at 25 megahertz. The workstation gained speed and efficiency, but even as these Motorola based systems improved, the computing landscape was beginning to shift. That same year, Sun Microsystems moved to its new SPARC architecture, signaling that the future belonged to RISC. Sony, too, began preparing for a transition. It was no longer just about making better workstations. It was about aligning with where the industry was headed.

By the end of 1989, Sony introduced the NWS 3860, its first NEWS model powered by a MIPS R3000 processor. The move to MIPS architecture was a major turning point. While Motorola chips had served them well, MIPS offered a simpler and more scalable design philosophy. It also came with a practical benefit: Sony’s own semiconductor division could license and build on MIPS technology in-house. This shift not only modernized the NEWS lineup but quietly laid the technological foundation that would later power the original PlayStation. What started as an internal decision about workstations would soon ripple far beyond the UNIX world.

During this same period, Sony also began experimenting with more network focused computing. The company introduced diskless workstations and X terminals that booted over Ethernet, reducing the need for local storage and moving toward centralized computing. These ideas anticipated the thin client and cloud computing models that would gain popularity decades later. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, this kind of thinking was rare. For Sony, it reflected a willingness to rethink not just the machine, but how people used it.

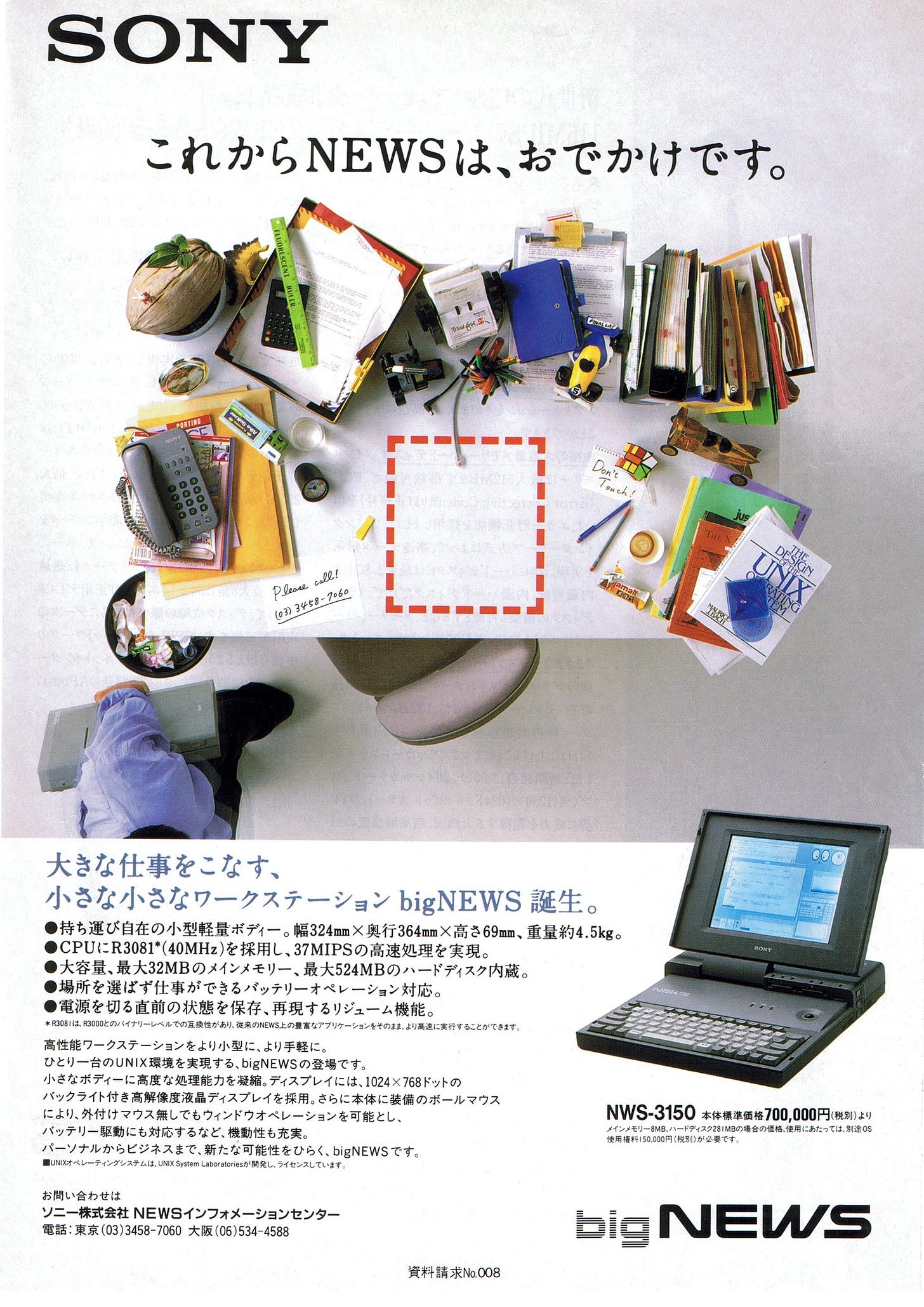

Sony’s foray into portable UNIX machines also began during this time. In 1990, the company released the NWS 1250, a heavy but movable workstation equipped with a 68030 CPU. Two years later, it followed with BigNEWS, model NWS 3150, which used a MIPS R3000 running at 40 megahertz. Without widespread access to the internet, these machines were better suited for engineers and developers who needed computing mobility within a single office or campus. They were not true remote work devices, but they pointed to a future where powerful tools would not be limited to desks or server rooms.

In 1992, Sony made another important change by shifting its operating system from BSD to System V Release 4. This was a strategic alignment. As the UNIX world became more fragmented, vendors were looking for ways to standardize. Sun had already moved from BSD to Solaris, and others were following. For Sony, adopting System V was a way to keep NEWS compatible with the broader enterprise environment and signal that its machines were serious contenders for professional deployment.

In 1995, Sony released the NWS 7000. It was a technical powerhouse, featuring four MIPS R10000 processors running at 200 megahertz with full 64 bit processing. On paper, it was one of the most capable UNIX workstations ever built by a Japanese company. But the timing was off. That same year, President Norio Ohga stepped down, and new leadership shifted focus away from enterprise workstations toward multimedia and consumer PCs. Tadashi Doi, the visionary behind the project, was reassigned and eventually left the company. He would later turn his attention to robotics and help develop AIBO, Sony’s robotic dog, before departing Sony entirely.

The NEWS series ran from 1987 to 1995. In that short span, Sony not only entered the UNIX workstation space but left a mark on it. NEWS connected the dots between high end development tools and multimedia experimentation. It showed what Sony’s engineering teams could accomplish when given room to explore and build for themselves.

The same MIPS architecture adopted during the NEWS era would later power the original PlayStation. More importantly, the culture behind it, with small teams working independently on bold ideas, helped shape how Sony entered gaming. NEWS did not transform the workstation market, but it quietly helped shape the future of one of the most iconic consoles ever made.

If you enjoy Obsolete Sony and want to support the work I’m doing, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your support helps me keep researching, writing, and sharing exclusive content. It makes a real difference and gives you early access to new projects, behind-the-scenes updates, and subscriber-only content. Thanks for being part of this!

.png)