It’s no secret that the Walkman influenced the iPod. And of course, Sony’s broader impact on Apple has been widely acknowledged, which makes sense given Sony's role as one of the most important tech companies of the 20th century. But the influence runs deeper. What truly shaped Apple’s early ethos wasn't just Sony, but a broader set of Japanese values: simplicity, craftsmanship, and a deep respect for the user experience. Steve Jobs didn’t just admire Sony’s products. He absorbed the cultural DNA behind them and reinterpreted it through a Western lens. Apple’s design language and user-first approach weren’t born in isolation, they were built on a foundation laid decades earlier across the Pacific. From the art prints that captivated him to the ceramics that refined his aesthetic, Jobs saw in Japan, and especially in Sony, a blueprint for fusing art and technology into tools that transformed lives.

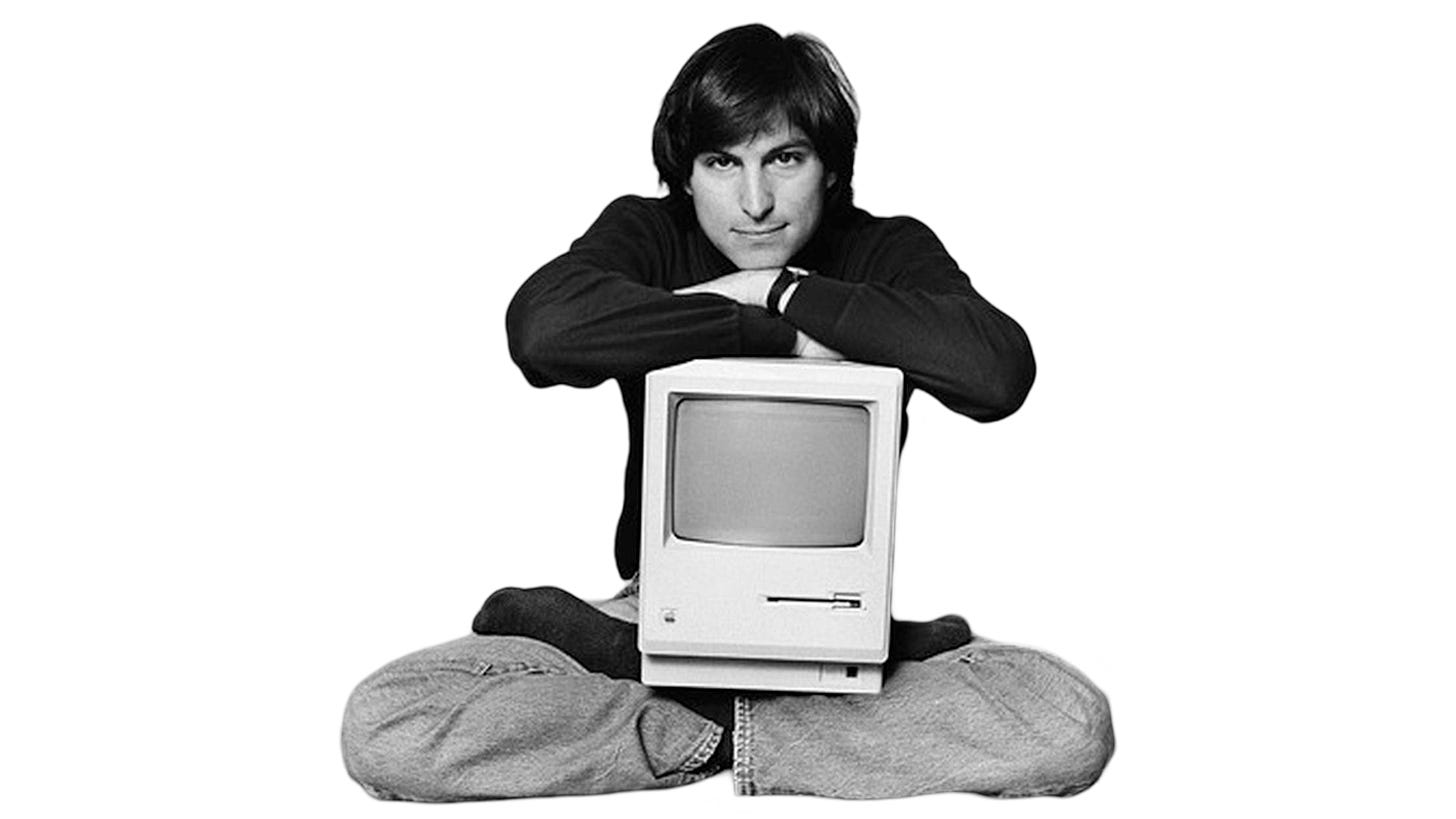

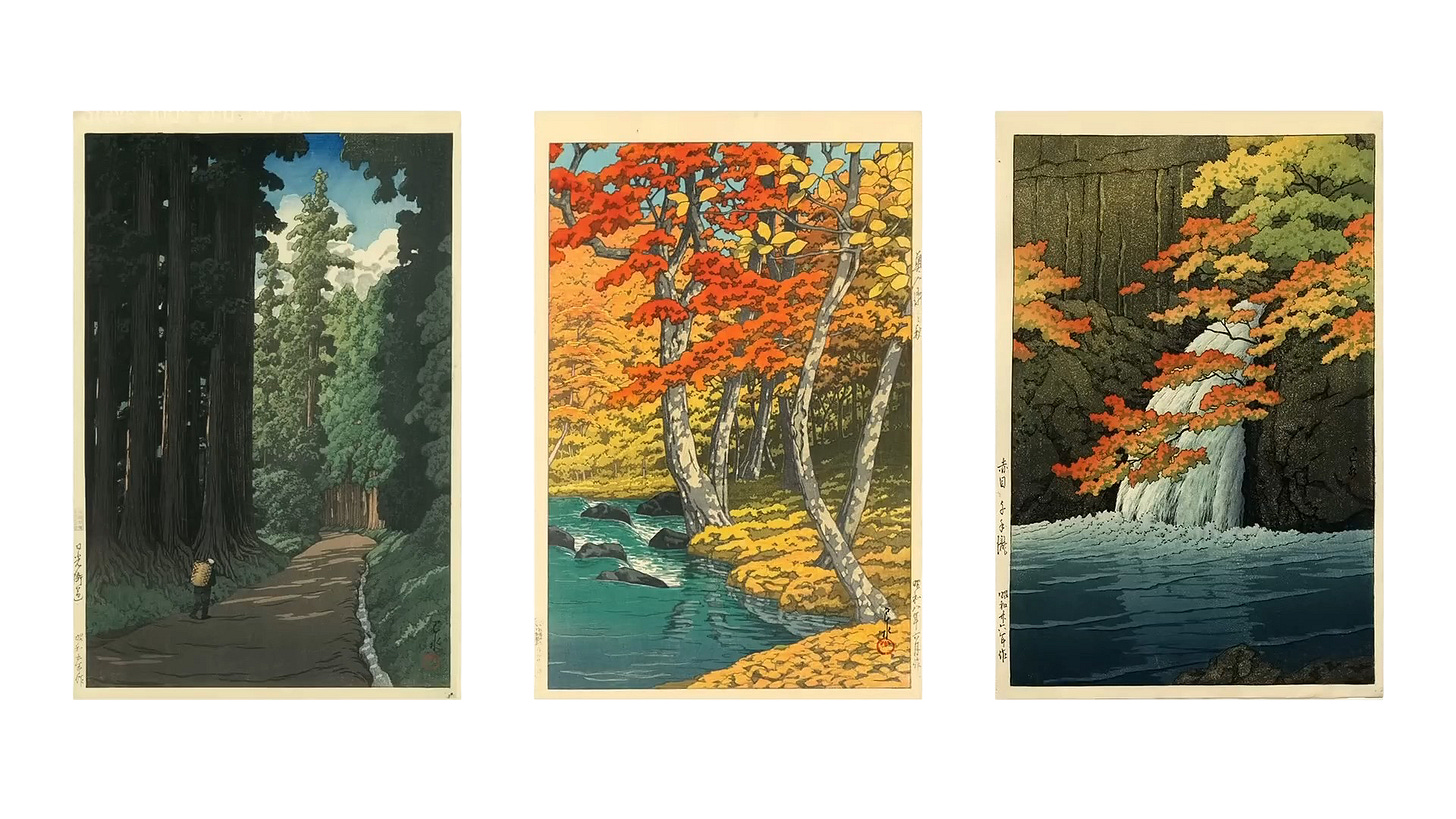

Jobs’ journey with Japan began in the living room of his childhood friend Bill Fernandez, who later became Apple’s first full-time employee. As a teenager in the 1960s, Jobs would visit the Fernandez family home in Cupertino, where the walls were adorned with shin-hanga, vibrant woodblock prints from Japan’s early 20th-century “new print” movement. Among them were three works by Kawase Hasui, a landscape master whose serene depictions of temples, rivers, and snow-dusted villages captivated the young Jobs. “He’d just sit there, staring at them,” Fernandez once recalled. “You could see something clicking in his mind.”

For Steve, Shin-hanga was a revelation. Artists like Hasui oversaw every step of creation, from sketch to carving to printing, ensuring their singular vision shone through. Decades later, Jobs would draw a parallel to his own work at Apple. “That’s what we’re doing with the Mac,” he’d say, introducing desktop publishing as a tool to empower individual creativity, much like a Japanese printmaker. Over 20 years, Jobs amassed 48 shin-hanga pieces, reflecting his lifelong passion for Japan’s meticulous beauty.

If Shin-hanga planted the seed, ceramics nurtured it into a full-blown love affair. Jobs first visited Japan in the early 1980s, and the country’s rich ceramic tradition captivated him. He was drawn to the tactile beauty of Raku tea bowls, earthy and imperfect forms that conveyed a sense of life and warmth. He also admired the delicate porcelain of Arita and Imari, its smooth, refined surfaces speaking to his love for simplicity and precision. "He’d hold a cup and talk about how it felt alive," a friend once recalled. Jobs even studied under a potter during one trip, marveling at the patience required to shape clay into something timeless. This reverence for craftsmanship and tactile experience would later echo in Apple’s minimalist designs: the smooth curves of an iMac, the satisfying feel of an iPhone, all whispers of the ceramic artistry Jobs had come to admire.

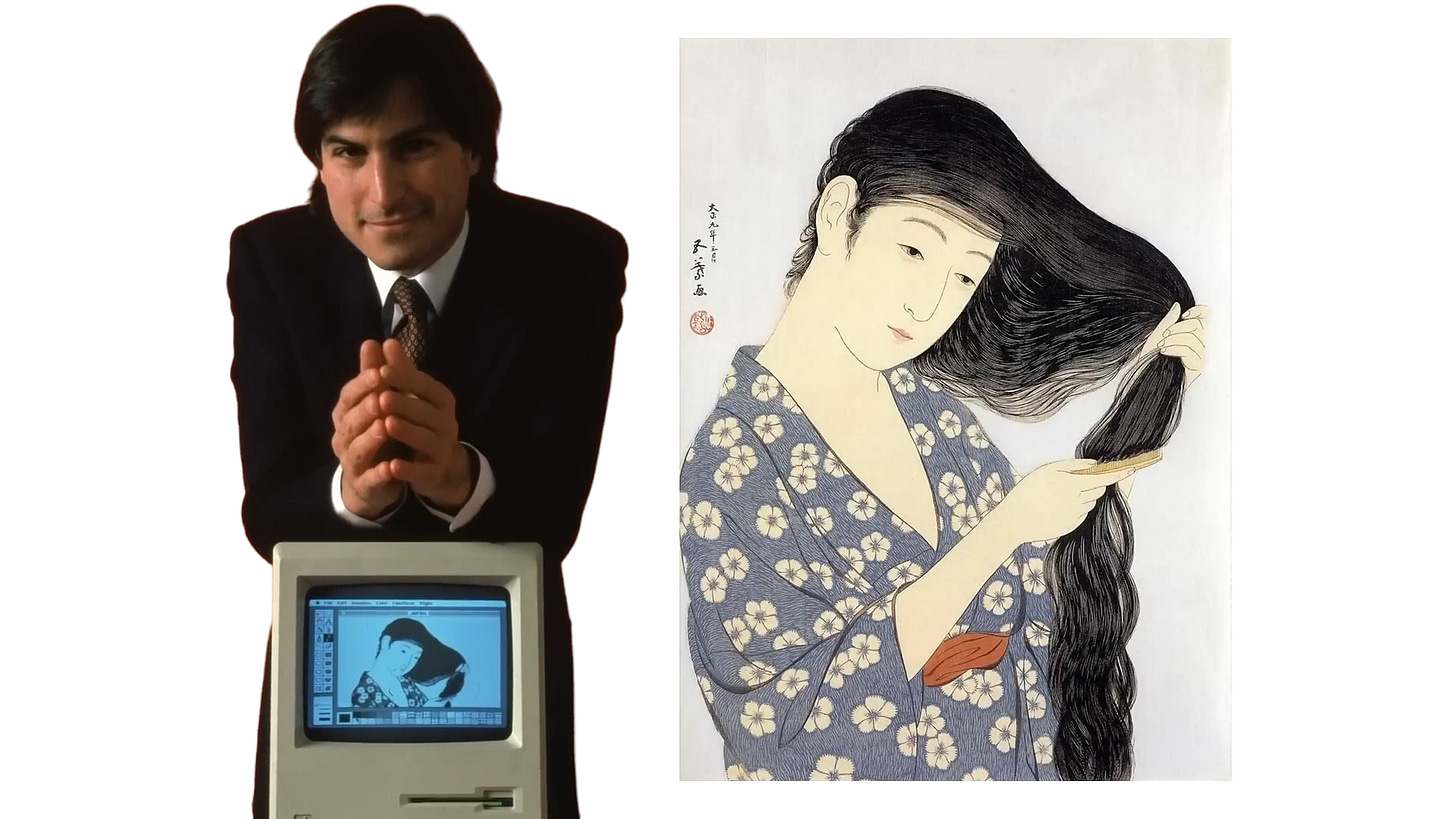

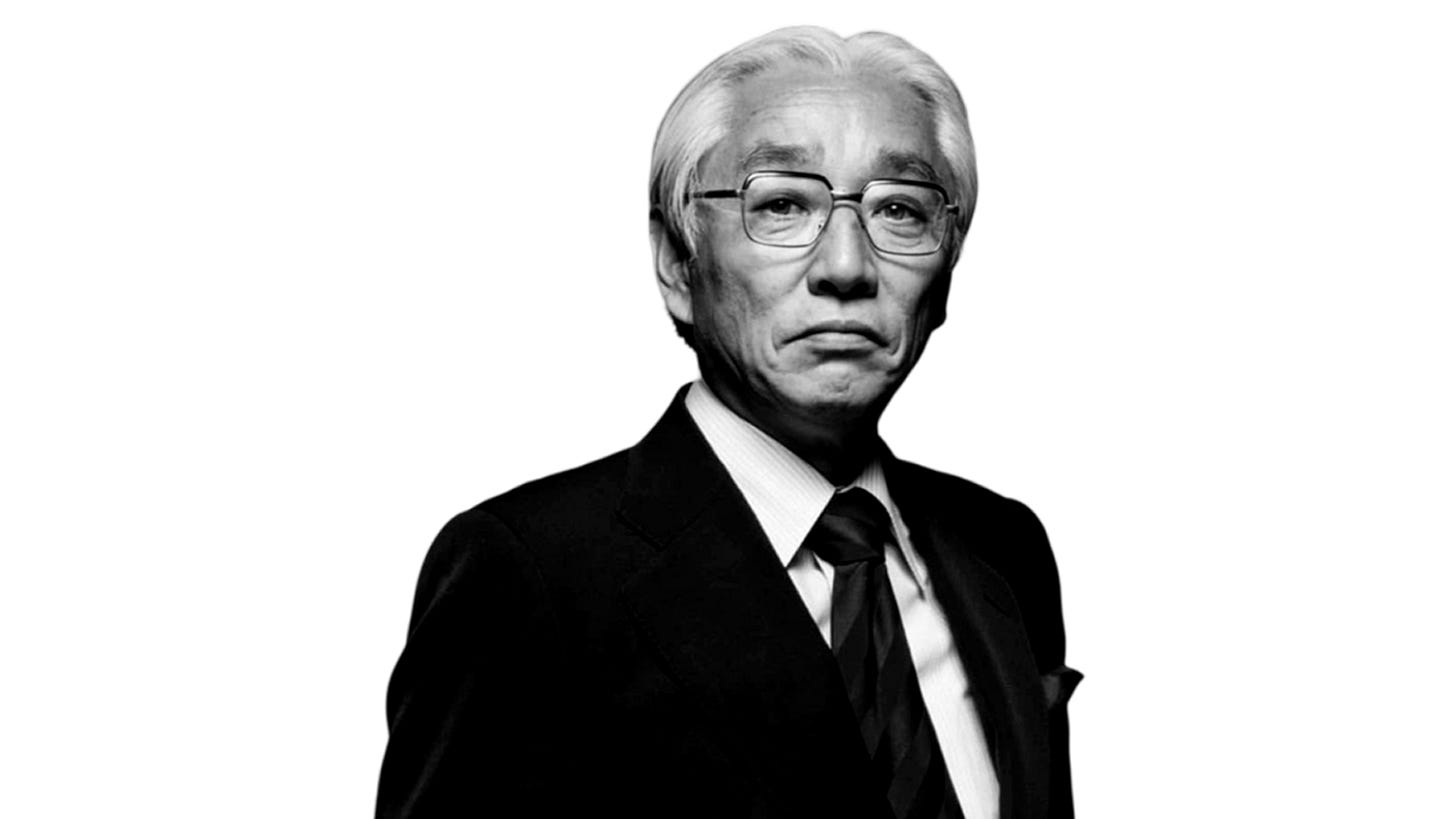

Jobs’ connection to Japan was deeply influenced by Akio Morita, Sony’s visionary co-founder. The two met in the early 1980s through mutual contacts in tech, and their bond grew over dinners in Japan, often at traditional ryokans. Over sake and kaiseki, Jobs hit Morita with questions about the Walkman. “How involved were you in the design?” he’d ask, scribbling notes. Morita, a “product person” like Jobs, loved sharing his philosophy: technology should enhance life, not complicate it.

Their friendship wasn’t just talk. Morita showered Jobs with gifts, like a pre-release portable CD player in 1984. Jobs was floored. “This is the spirit of Japanese manufacturing,” he told John Sculley, Apple’s then-CEO, before dissecting it with engineers to study its precision. Morita, in turn, saw in Jobs a kindred spirit, a restless innovator who could marry art and engineering. Their mutual respect hinted at something deeper, a possibility that in 1985, nearly came to pass.

Jobs’ Japanese inspirations extended beyond art and craft to fashion, where designer Issey Miyake left an indelible mark. On a business trip to Japan in the 1980s, Jobs encountered Miyake’s lapel-less jackets for Sony factory workers. Made of ripstop nylon with detachable sleeves, they were practical yet stylish, a hallmark of Sony’s design ethos. Jobs asked Miyake to create a uniform for Apple employees, envisioning a cohesive identity for his team. The idea flopped. Apple staff “booed him off the stage,” he later told biographer Walter Isaacson, but Miyake’s genius stuck with him.

Instead, Miyake crafted the black mock turtleneck that became Jobs’ signature. “I asked Issey to make me some of those black turtlenecks I liked,” Jobs recalled, “and he made me like a hundred of them—enough to last the rest of my life.” Worn daily, that garment linked Jobs’ personal style to Japan’s design legacy, with Sony as the unwitting catalyst. Miyake, who passed away in 2022 at 84, bridged tradition and innovation—qualities Jobs mirrored at Apple.

By mid-1985, Jobs was adrift. Ousted from Apple after a boardroom clash, the 30-year-old prodigy faced an uncertain future and Morita saw an opening. Sony was dabbling in personal computing. The SMC-70 had launched in 1982 but lacked the bold vision to rival Apple or IBM. Morita, nearing 65 and eager to secure Sony’s next leap, reportedly offered Jobs a role. Details are murky. Some say it was to lead Sony’s PC efforts, others suggest a broader creative mandate, but the intent was clear. Morita wanted Jobs’ magic touch.

The offer wasn’t far-fetched. Jobs idolized Sony, carrying a Walkman everywhere and praising its design philosophy. He’d even poached Sony designer Hartmut Esslinger in 1983 to shape Apple’s look, inspired by Sony’s unity of design and production. A dinner with Morita in Kyoto might’ve sparked the idea. Perhaps over bowls of Jobs’ beloved Raku, a casual remark like, “Why not join us?” turned serious. Jobs, reeling from Apple, was tempted. Friends remember him speaking highly of Sony’s resources and how much he valued Morita’s mentorship.

Yet he declined. Sony’s hierarchical culture clashed with his need for control. “He’d have been a lion in a cage,” Esslinger later said. After weeks of soul-searching Jobs declined, founding NeXT instead. It was a gamble that paid off, but the “what if” lingers.

Jobs’ refusal didn’t dim his love for Japan. At NeXT, and later back at Apple, he channeled Akio’s lessons: simplicity, craft, collaboration. The iPod, born from his Walkman obsession, toppled Sony’s digital music dreams, a poetic twist. His Shin-hanga hung in his Palo Alto home, and he returned to Japan often, refining his vision.

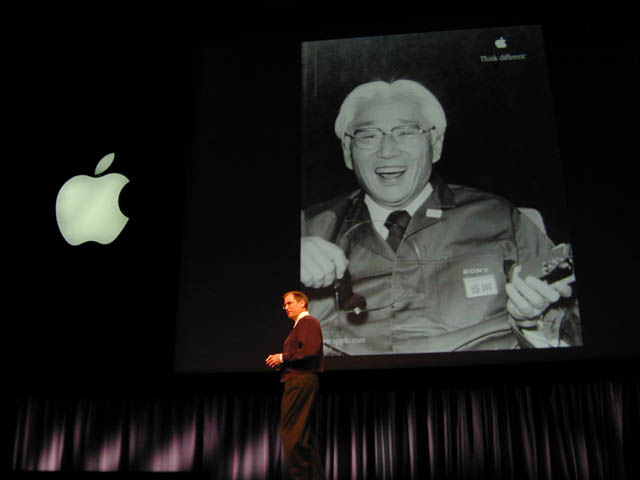

On October 6, 1999, during an Apple keynote, Jobs paid tribute to Morita, who’d died days earlier. A photo of the Sony founder flashed onscreen with “Think Different.” After a silence, Jobs spoke of Sony’s early influence—how Morita’s Japan shaped him. “Apple’s soul is half-Japanese,” Esslinger once quipped, and it’s true.

If you enjoy Obsolete Sony and want to support the work I’m doing, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your support helps me keep researching, writing, and sharing exclusive content. It makes a real difference and gives you early access to new projects, behind-the-scenes updates, and subscriber-only content. Thanks for being part of this!

.png)