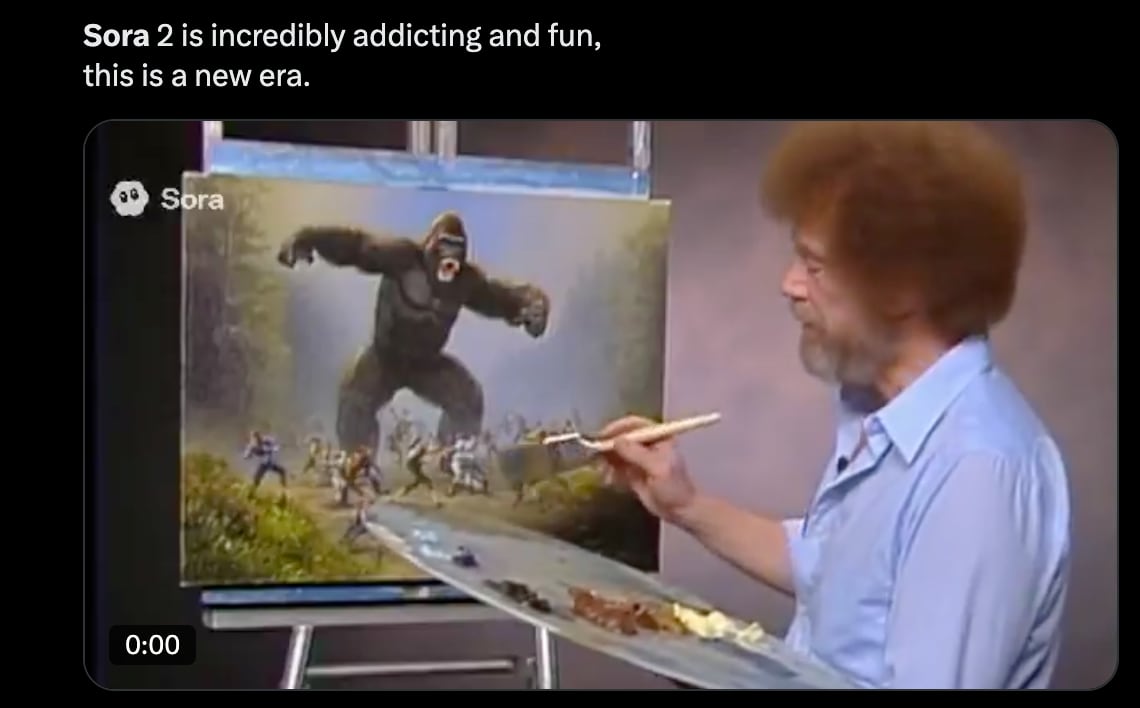

If you’re online at all, you’ve probably seen that OpenAI has released a new social app called Sora. It is a TikTok-style iOS app, but the catch is that it shows AI generated short-form video, generated by the Sora 2 model. It has a “cameo” feature, wherein you can create hauntingly accurate deepfakes with someone’s face (be it a friend or public figure, like Sam Altman—OpenAI’s CEO).

Entertainment! Entertainment?

After all, is this what it’s for? Right?

Let’s see how OpenAI describes it:

We first started playing with this “upload yourself” feature several months ago on the Sora team, and we all had a blast with it. It kind of felt like a natural evolution of communication—from text messages to emojis to voice notes to this.

Sam Altman, on X, waxes about how it unleashes “creativity”:

This feels to many of us like the “ChatGPT for creativity” moment, and it feels fun and new. There is something great about making it really easy and fast to go from idea to result, and the new social dynamics that emerge.

Creativity could be about to go through a Cambrian explosion, and along with it, the quality of art and entertainment can drastically increase. Even in the very early days of playing with Sora, it’s been striking to many of us how open the playing field suddenly feels.

In particular, the ability to put yourself and your friends into a video—the team worked very hard on character consistency—with the cameo feature is something we have really enjoyed during testing, and is to many of us a surprisingly compelling new way to connect.

Note the emphasis on “fun,” “art,” and “entertainment” — there’s a tacit acknowledgement that what these models do best is reproduce content and particularly memetic content. Potentially powerful stuff in this attention economy.

Adam Aleksic (@etymologynerd), a linguist and scholar of online media and digital platforms, pointed out at a recent talk I attended how “content” comes from the notion of filler (the word “content” derives from Latin contentum, meaning “that which is contained,” itself from continere, which means “to hold together, enclose.”), something that can be contained by the platform. There’s an intrinsic flattening of calling something content. Art, entertainment, memes, all appear in the same feed. In light of this, there’s a sense that the platform itself is indifferent to the provenance or even meaning of the content—it just needs filler to contain.

While Sora remains guarded behind invite codes, it already is giving rise to uncanny and strange uses of the cameo feature. Spongebob appears as Hitler. Pikachu robs a CVS on security cam footage.

Meaning works by association. Exposure to a piece of media can create rippling activations of association in the beholder. The cameo feature jacks into this by leveraging familiar associations: friends, public figures, beloved (copyrighted) characters (like Pikachu or Spongebob), and other nostalgic figures, placing them in uncanny contexts and scenarios (like robbing a store) to create an attention attractor — something that’s hard to look away from. The result is fun, sure, but also potentially addictive, unsettling, or even upsetting.

These are videos of events that never happened, that weren’t even imagined. They aren’t fictional in the traditional sense (no creative lie was told), they’re pure content: automagic filler for an infinite scroll that can attenuate to the user’s dopaminergic preferences, conditioned off their particular cultural associative patterns. The “creativity” injected in them is the way human prompting (and mimesis), paired with a recommender algorithm, searches towards the most addictive, eye-catching content.

When the feed becomes an infinite scroll of never-events optimized for maximum attention capture, what happens to our ability to perceive actual events? To distinguish between what matters and what’s just engineered to be compulsively watchable? Not only might we be unable to distinguish between a dance clip and a never-clip mimicking it, we might find our feeds resembling a hall of mirrors: uncanny reflections of events that never happened, were never imagined, were never “created” in the intentional sense to be seen.

Not only does the platform hijack attention, it hijacks imagination itself, by leveraging human humor and creative mimesis to create yet more filler and addiction-fodder. Humans decide what signs to charge and juxtapose, something machines are still not great at, and yet this also creates a web of patterns that can be trained upon, eventually doing away with human imagination entirely. It’s easy to imagine a future where each never-clip was synthesized from nothing: autonomous entertainment from cradle to grave.

For now, Sora Media is mostly contained to the app, but increasingly they’re already escaping into the wider platform media ecosystem. I anticipate even in the coming days, Sora-generated content will start to fill the larger algorithmic platforms with generated content. Like a plume of slop, it will spread through the internet. Hyper-attuned media that one simply can’t look away from, get hooked on. How will this reshape the internet? Meaningless media filling the feed, all for the purposes of “fun” and “entertainment” and (of course) profit.

Synthetic meaning (what I’ve been calling “synthetic semiosis”) is something we don’t fully understand, especially longitudinally. We’ve begun to see cases of how long winding conversations with ChatGPT can trigger psychosis—something we might express as prolonged exposure to synthetic meaning loops. What happens when suddenly our cultural reference points become synthesized never-events? We don’t fully know the nature of this substance, its effects on the mind, or on the collective psyche, and yet intuitively it feels hazardous.

What can be done? One wishes for regulation. It may come, it may not. A managed retreat into the “cozy web” — behind socially activated membranes of meaning feels more likely. Protecting one’s attention from the feeds, relying on organic, social networked curation might provide some salve and protection as the plume spreads. And the plume is spreading.

In a 1996 interview, David Foster Wallace predicted: “I think the next 15 or 20 years are going to be a very scary and sort of very exciting time when we have to sort of reevaluate our relationship to fun and pleasure and entertainment because it’s going to get so good, and so high pressure, that we’re going to have to forge some kind of attitude toward it that lets us live.” (source) Does that attitude mean managed retreat from the algorithmic feeds? Epistemic grounding in the real when internet culture giggles nihilistically at the slop trough? The alternative is infinite meaninglessness.

.png)