Yesterday I won some bets that I made almost five years ago. These weren’t simple bets like “a different party will hold the Presidency” or “The CCP will be governing China in 2025”. Rather, I made a stack of nineteen bets on America’s pharmaceutical and biotech future with a few friends of mine and I got the first bet on the money with only a few months to spare. If you’ve been paying attention to the news, you may have heard that Regeneron bought 23andMe. As predicted:

Caveat: Not all of my proposed bets were accepted and there are some below these in another comment that I’m less likely to win. Whatever! That’s neither here nor there. What I really want to say is this:

When someone predicts something unusual five years ahead of time, you should wonder why.

In mid-2015, Matthew Nelson and colleagues published a groundbreaking paper. They found that when the mechanisms of different drugs were also implicated in genetic studies, the odds that those drugs would be approved were doubled (OR = 2.1).

This is very large given the domain. In general, only about 10% of all drugs subjected to the trial process eventually receive FDA approval. Going from just under 10% approvals to nearly 20% is a huge change for the industry given the enormous cost and complexity of trials. Per the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), clinical trials comprise a little over two-thirds of out-of-pocket R&D expenditures, averaging $117.4 million per drug brought to market.

More critically, the HHS’ report found that, after accounting for capital and failures, the average drug brought to market costs $879.3 million. The importance of prioritizing drug targets that are likely to be approved should make financial sense given these figures: the better the prioritization before trials commence, the higher the savings and the more likely the company investing their precious R&D time and dollars stays afloat.

“Precious” is perhaps an understatement given the sad state of pharmaceutical R&D:

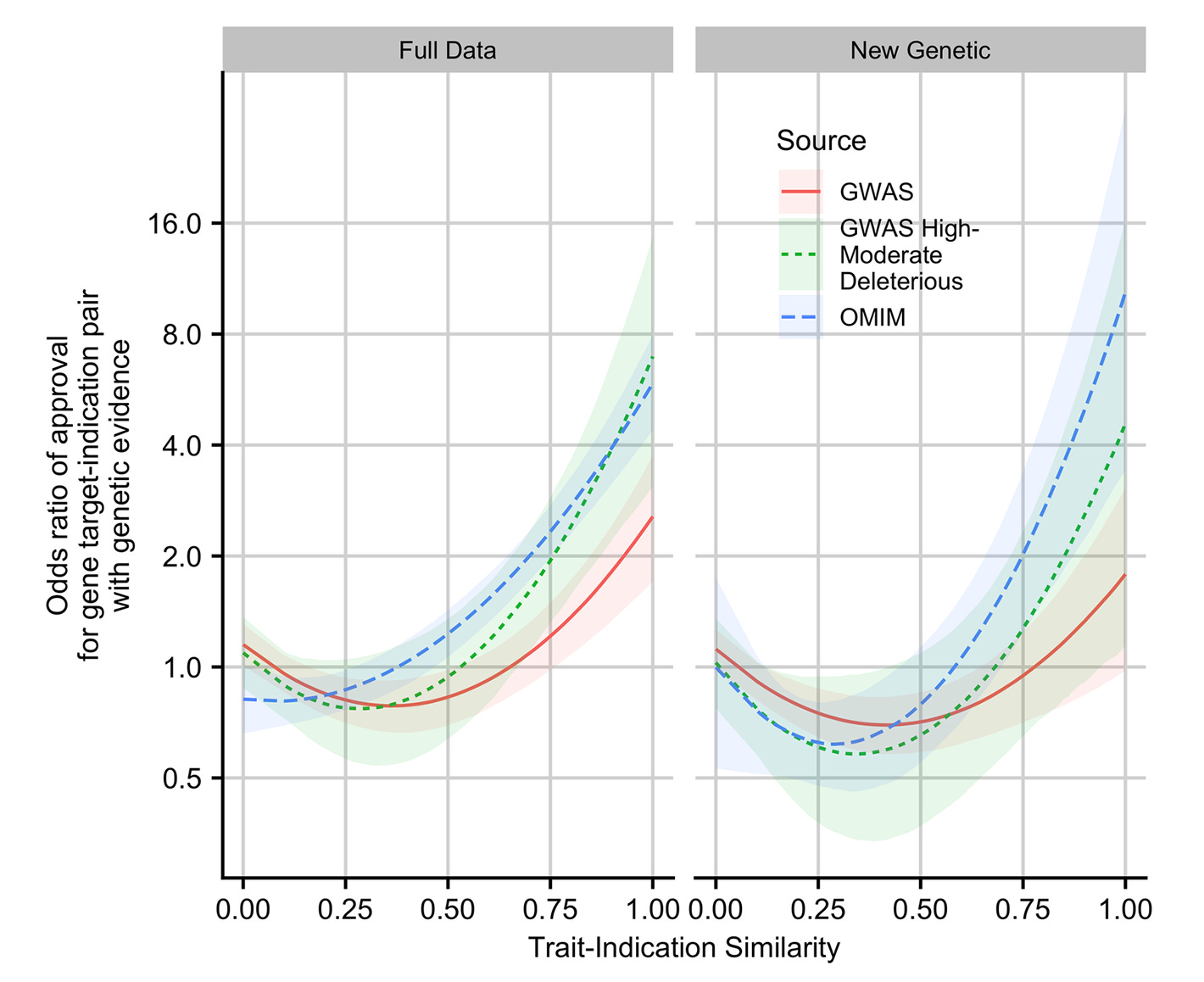

This is why the 2019 follow-up by King, Davis and Degner is so important. In that study, they updated the data from Nelson et al. and extended their methods. New data in hand, genetic support was even more strongly related to the likelihood of an approval. This was particularly true when the genetic evidence concerned Mendelian traits and when GWAS associations were linked to coding variants. Furthermore, the more similar the drug was to its genetic counterpart, the greater the odds the drug would be approved, up to a nearly nine-times improvement in approval odds.

In 2024, Vallabh Minikel et al. added even more data, finding that genetic evidence was associated 2.6-times higher odds of approval. This is an especially powerful finding because so much genetic evidence had been produced by this point from GWASs. At baseline, a huge number of drug targets should have already been incidentally supported for this reason, and indeed, that is something they found. Adding to the other studies, Vallabh Minikel et al. found that genetic evidence could even affect the odds of moving from preclinical studies to real clinical trials.

Shortly after Vallabh Minikel et al.’s study, the 23andMe Research Team published their own report on the matter. Was this an attempt to salvage the buying price for 23andMe with bankruptcy looming? Was it the Research Team crying out about mismanagement? Even people within the Team are torn on the motivation for this study, at least when I’ve asked them. Regardless, their findings are substantial because of how they differed from earlier results.

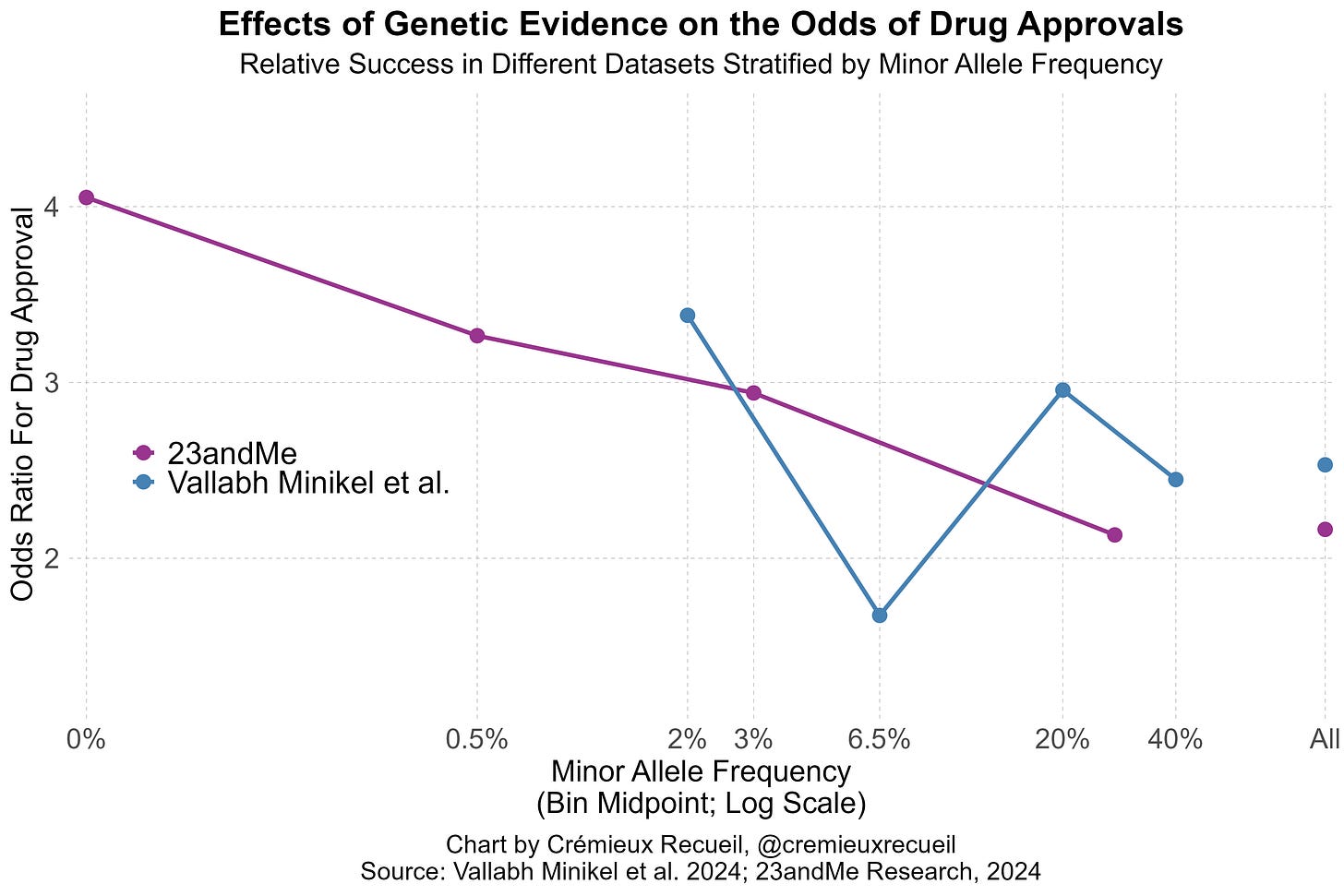

Vallabh Minikel et al. had lots of data and produced up-to-date estimates of the impacts of genetic evidence on clinical success. Their paper was no small feat, but it revealed a major weakness: the data they had access to did not leave them with enough statistical power to detect the positive association between the effect sizes of different variants or the inverse of their minor allele frequencies and the odds of clinical success.

In 23andMe’s data, they provided evidence that both of these factors influenced drug approval odds. Both factors are predicted to do so based on strongly supported genetic theory; the larger the effects and the rarer the variants, the more likely those variants are to be causal and to discretely disrupt a target-relevant function, but Vallabh Minikel et al. still failed to find those effects.

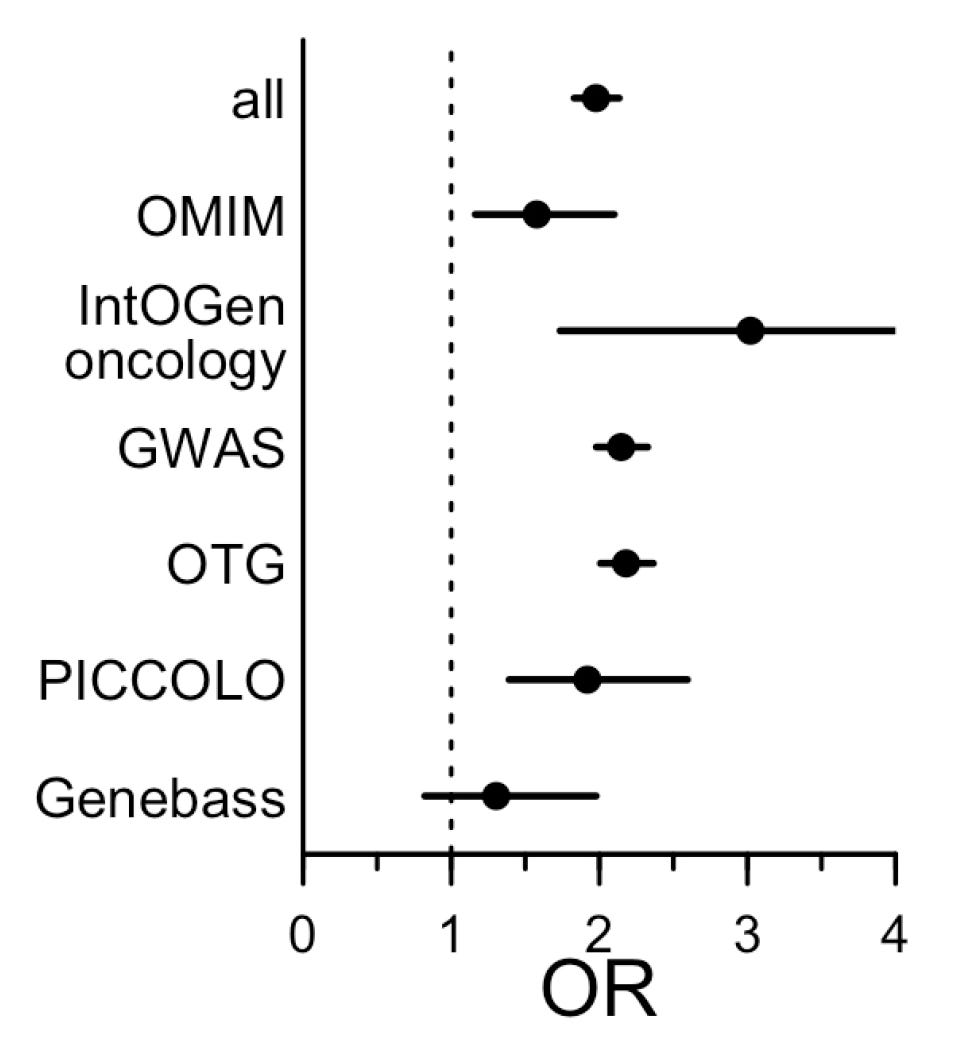

I’ve illustrated the comparative results stratified by minor allele frequency like so:

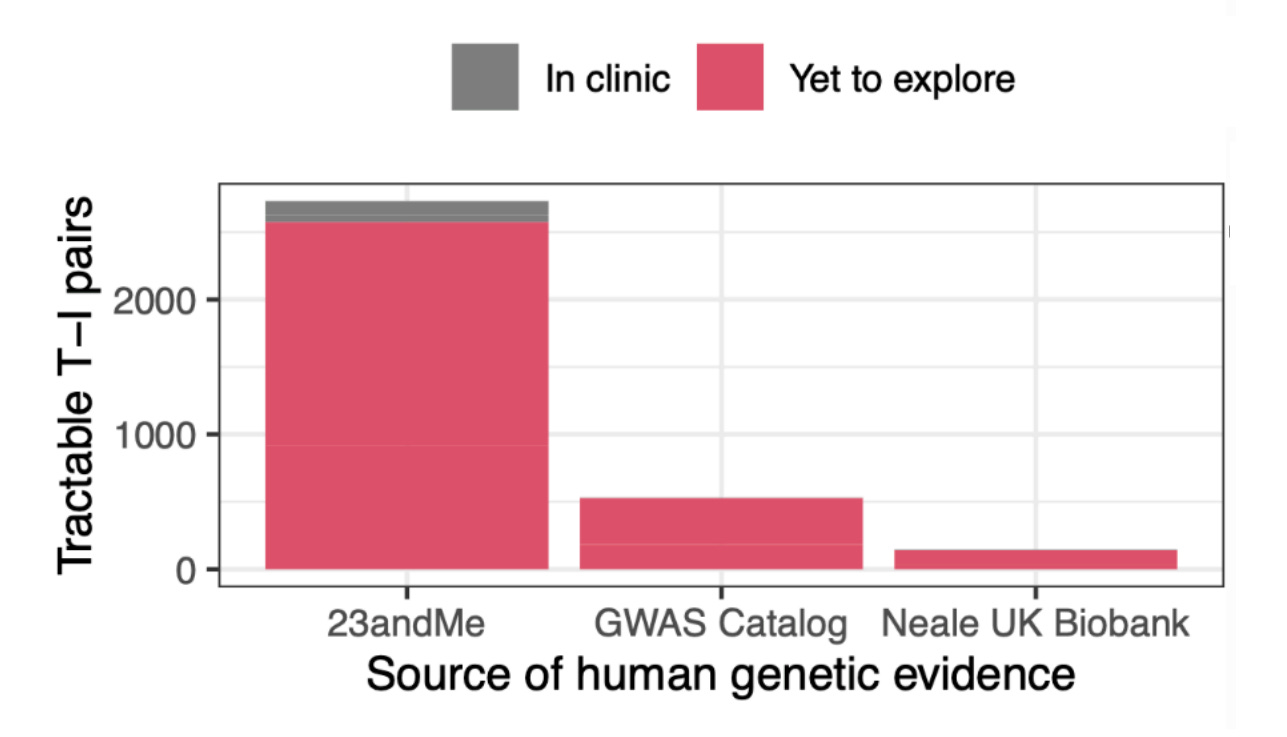

What these findings indicate is simple and elegant: even today’s massive public datasets are not enough. 23andMe is that much larger, and they deliver results that are better predicted by theory. Because of this fact, 23andMe’s data is also more amenable to predicting success. The Research Team knew this and they provided a lot of talk about power in their paper. Moreover, they went on to show that their large dataset allowed for better indication of whether variants were causal—a key predictor of approval. Not only that, but their power showed up in terms of numbers of findings:

23andMe has won by virtue of size, but they’ve also won by virtue of another of the paper’s findings: self-reported data works fine! With that finding in hand, the true value of the 23andMe platform should be clearer. Not only does 23andMe have a lot of data and not only have they already done a lot of phenotyping of their customers, but they also have a platform that will let them go further, letting them do far more extensive phenotyping of tons of traits. They could even request people go out and get and report medical results to them. That’s legal!

To review (I), Regeneron’s purchase has provided them with the motherlode of data to prioritize drug targets. This greatly increases the odds of success picking drugs that will work when they go to trial. With further growth in and use of the platform, that’ll only become more true. This supersedes their existing sequencing efforts.

But prioritization is not discovery. Actually discovering novel drug targets is more difficult than prioritizing existing ones to focus on as a vetting step before proceeding to clinical trials. Most datasets and biobanks are not set up for doing that, but 23andMe is exceptional. Recall that 23andMe is a platform that allows gathering more data and also that most of the people who use 23andMe have agreed to supply their data for research purposes. Not only that, but many of them would like to supply more data.

By leveraging its data collection capabilities, it’s possible to validate and seek out new drug targets through expansive phenotyping, to provide more support for drug target causality through little-used but highly-informative methods following from things like family-based genotyping, and to contact the roughly 10% of 23andMe customers who have rare diseases and other unusual conditions for outright target discovery.

Most examples of prospective genetically-assisted drug target discovery are based on the identification of people who are unusual.

For example, PCSK9, a gene that regulates cholesterol metabolism, was discovered as a viable drug target shortly after two gain-of-function mutations were found in a pair of French families that had clinical diagnoses of autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia (high cholesterol) without any mutations in the LDLR or apoB100 genes. After the discovery of PCSK9’s involvement in cholesterol levels, it was then discovered that two loss-of-function mutations in African Americans (Y142X and C679X) came with major reductions in LDL levels and heart disease risk. Additionally, the R46L loss-of-function mutation found among White people was associated with a somewhat smaller reduction in LDL levels and heart disease risk.

These genetic discoveries led to work on figuring out how to inhibit PCSK9 in humans. That work resulted in PCSK9 inhibitors, which are a successful alternative to statins, with pronounced benefits for those who cannot tolerate statins. I will return to people like these later.

To review (II), Regeneron has acquired the ability to do target discovery better than anyone else is currently capable of doing. There is precedent for these methods working, but few have had the requisite data and collection platforms to make this possible at scale. Regeneron got those things and we know they want to use them.

Pharmaceutical companies aim to go beyond improving target selection to reduce failure rates—the main source of costs in drug discovery—due to drugs lacking efficacy, to also predict their side effect profiles. About half of trials fail due to efficacy problems, a further quarter fail due to safety issues, and a bit under 5% of drugs are also eventually withdrawn from the market. By predicting which drugs will fail for safety reasons, companies can prevent lawsuits and costly mistakes introducing compounds to market or trials.

The ability to and utility of profiling side effects from genetic data has been demonstrated in numerous ways. For example, Nguyen et al. found that “the existence of a genetic association between a drug’s target(s) and phenotypes in a given organ system increases the probability that a side effect will be observed in that organ system during clinical trials.” Moreover, they found that genetic data can be used to predict side effects in off-indication organs and—even more importantly—that when there was genetic support for a drug’s target affecting other phenotypes but not a particular interrogated phenotype, the rate of side effects observed in the interrogated phenotype is reduced. In other words, “human genetics provides evidence that can be used to de-risk targets.”

More recently, “[side effects] were 2.0 times more likely to occur for drugs whose target possessed human genetic evidence for a trait similar to the [side effect].” One especially useful finding was that genetic evidence was more powerful when side effects were more common among patients and when they were more severe.

As with predicting drug trial success, the results were augmented by similarity, this time between the side effect and the trait. Armed with this knowledge and the ability to do extensive phenotyping with ease, Regeneron can get a lot more out of side effect prediction than anyone else. But predicting side effect profiles is not all they’re going to be more capable of than peer companies. They’ll also be able to better ascertain carcinogenicity and they can leverage genetic information to conduct cost-effective safety studies and improve monitoring.

To make the possibility and utility of side effect profiling clearer, consider a concrete example: the claim that ezetimibe—a statin alternative based on Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1 (NPC1L1) protein rather than the HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR) enzyme targeted by statins—causes cancer. To figure this out, you might need a very large trial with a sample monitored for a long time, or you could use the natural genetic variation in LDL levels provided by individual differences in the NPC1L1 gene.

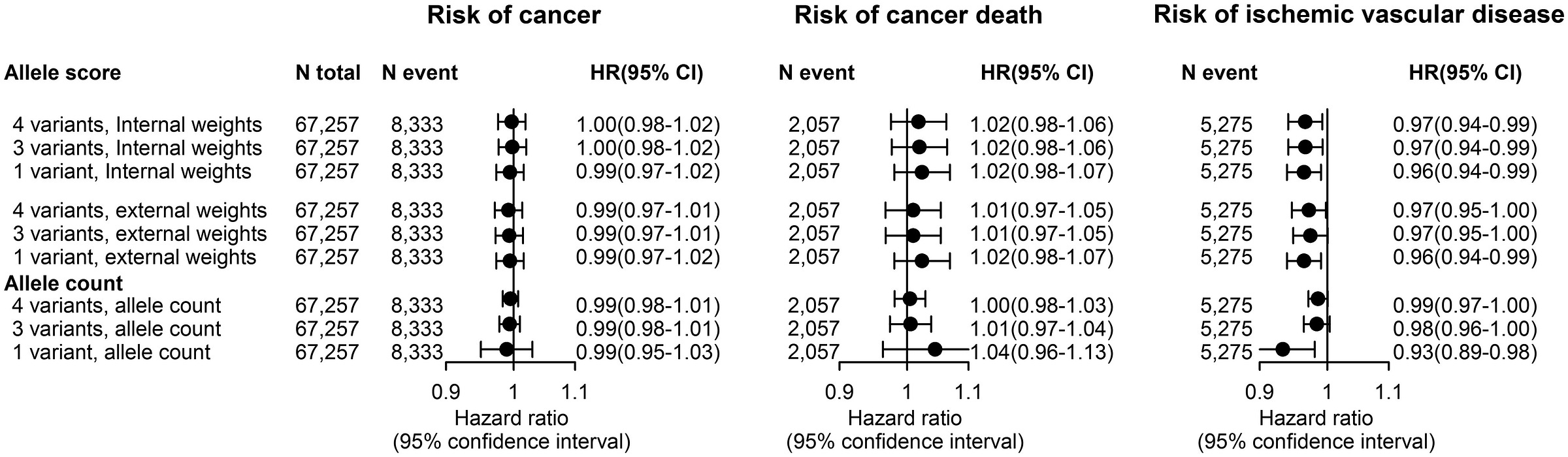

Differences in NPC1L1 index differences in lifetime LDL levels in a way that’s equivalent to the lifetime effect of taking ezetimibe at different doses. With data on people with different variants affecting the effect of NPC1L1, we can see that there’s no cancer risk from the drug:

With that concern out of the way, there’s still the question: what if ezetimibe is harmful in some other way? One could argue that statins are better studied and so we know they’re safe, whereas ezetimibe’s safety is a more open question. To answer it, turn first to studies of statins. The metabolic changes associated with starting statin therapy are indistinguishable from the effects associated with variation in the HMGCR gene:

The genetic and the pharmacological effects of statins are effectively identical. It is likely that characterizing the effects of one characterizes the effects of the other. The effects of statins—which are based on HMGCR—and variations in PCSK9 are also highly, but somewhat less, similar. To bring the third major LDL-lowering option, ezetimibe (NCP1L1), back into this picture, we can compare it to statins. As it turns out, the metabolomic profile of genetic variation in NCP1L1 is effectively identical to the metabolomic profile of genetic variation in HMGCR.

The important things this exercise suggests are that the side effect profile of gene dosage is similar to the side effect profile of corresponding drugs, and that these particular drugs should be broadly similar. For most purposes, it’s likely that you’ll be able to safely generalize from conclusions made about one drug to the others in this class. Regeneron can straightforwardly create this sort of profile or a map of other correlates for many drug targets. From this, they’ll be better equipped to handle pretrial safety considerations than anyone else.

To review (III), Regeneron has acquired the data and platform that, when used properly, will allow them to upend the traditional process of drug development, letting them do it more effectively and cheaply, while avoiding costly missteps. They’ll also be able to ascertain whether most side effect reports are real or erroneous, allowing them to provide cover for their drugs when the public inevitably overreacts to potentially false information, like that GLP-1RAs cause higher bodyfat percentages or that ezetimibe causes cancer.

The other big thing that will become available to Regeneron right away is the data required to reliably do repurposing. To use a recent example, Novo Nordisk’s Ozempic is approved for the management of chronic kidney disease. Anyone working on GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) could’ve known to pursue this if they leveraged genetic data. Why? Because variation in the GLP1R gene causes lower rates of chronic kidney disease and the effects of variation in GLP1R are similar to the effects of GLP-1RAs.

Seeing a sizable effect through genetic evidence and knowing that variation in GLP1R or even that GLP-1RAs themselves are safe, running a trial for a costly condition becomes a gambit with a high expected value. Indeed, it’s likely that Ozempic makes a ton on being prescribed for chronic kidney disease, since it is common and costly and Ozempic helps to treat it while appealing to patients on other dimensions like providing diabetes and weight management.

The possibility of doing genetically-guided repurposing is problem one of the most readily accessed ways to bring a drug to market for a new indication. There are many techniques available for doing this, the missing link for doing this at scale has always just been data. Guess who now has data and a platform to collect it?

To review (IV), Regeneron has positioned themselves in an opportune way to start taking existing drugs and getting them approved for alternative indications that can be highly lucrative to pursue. They can also use this sort of data to provide off-label prescription indications and vetting for doctors and other providers, if they so wish. Doing that can lead to very large increases in prescriptions, as will likely be the case when GLP-1RA generics arrive for diabetes and get prescribed off-label for obesity.

Turn back to statins. They’re commonly prescribed and they’ve saved countless lives, but they were once feared: their story almost tragically ended before it could begin. In their first administration, the Japanese scientists who discovered them got very unlucky by testing them on one of the roughly one-third of people who experience myopathy—muscular weakness—when they’re given. Not only that, but they administered the drug to a woman who was in the even smaller minority for whom the myopathy was severe. She eventually became unable to walk while on the drugs, and statin tests were officially stopped. Luckily, they continued in secret and the discoverers found that they could reliably lower cholesterol levels at low doses, safely and effectively for most people.

A few decades later, two teams of researchers may have stumbled upon the mechanism behind statin-induced myopathy. The first team may have found the answer through investigating nine people with serious muscular dystrophy, all but one of whom was discovered to carry missense mutations in the HMGCR gene. That team’s work was done on unrelated people, but the second team’s research was done on an inbred Bedouin Arab family in Israel. In this family, several of the individuals suffered from the same condition seen by the first team, both phenotypically and seemingly genetically.

In both studies, the responsible mutations were likely the ones in HMGCR, implicating a critical component of how statins function. Statins operate by inhibiting HMGCR from converting to HMG-CoA to mevalonolactone, and these mutations cut off the conversion to HMG-CoA. The team working with the bedu family decided to act on this information. They started administering one of the affected people a weekly dose of mevalonolactone, the product of HMGCR.

Within three weeks, she had clearly begun to recover muscular function. She did so without any noticeable bump in cholesterol levels. This experiment was repeated in a mouse model of statin-induced myopathy and it was found that supplementing mevalonolactone had the same effect for mice as it did for their human test subject: no myopathy! The mice that were just given statins couldn’t hold onto a wire for very long, but the mice who were given the statins and the mevalonolactone were just as strong as they were before therapy began:

By looking at unusual people and their families, these researchers may have found a treatment for a common side effect of statin use. This could become a standard treatment for people who take statins and suffer from myopathy, potentially helping millions globally to lower their cholesterol safely.

To review (V), Regeneron is now set up to replicate this scenario for tons of different drugs, many of which do not have alternatives like statins do. Selling the cure for a bad side effect could be extremely lucrative. To find more things like this, Regeneron just has to leverage their ability to contact people effectively. They could even provide people with free sequencing for their families when they’re using them to potentially make medical discoveries like this one. This paves the way for simple N-of-1 therapies and therapeutic discoveries for the masses based on rare disease findings.

Now is the right time for a 23andMe purchase. The new Presidential administration has explicitly ordered that regulators deprioritize enforcement actions that stand in the way of technological advances and Regeneron is poised to make many technological advances. At the same time, the administration is pursuing deregulation and reform, and they’ve signaled an interest in significant overhauls to how clinical trials and cGMP are done in the U.S. These reforms would make trials far less costly.

Tearing down barriers to patient contact and recruitment alone would put Regeneron in a very good position, because they can now use their platform to find people for trials at a larger scale and more effectively than practically anyone. Recall again just how willing 23andMe participants are to supply medical information, participate in surveys, and so on. No doubt some number of them would even be willing to take part in trials, potentially reducing the compensation issues clinical trials face through selection.

If America widens its acceptance of overseas data—as its anti-animal testing plans indicate it should—then Regeneron will even be able to run trials or trial segments abroad quite cheaply. This is advantageous for them more than for so many others simply because of the number of plausible targets they have available. These vetting tools turn into relatively sure bets and enable fast progress coupled with the changes that are soon to arrive to the regulatory ecosystem.

All of this is really just the beginning, too. Regeneron is, for many reasons, in a very fortuitous position because of who’s in office.

Recall that report on the cost of trials cited by the HHS. It includes a section on estimates of how different strategies and tools can impact the costs and time spent in drug development.

Where surrogate endpoints are viable, Regeneron can save money with them because their data gathering is simplified and expedited through their platform, and they may have or be able to obtain pre-existing measurements for many things as well. The report estimated using these could save 1-5% on costs and 1-3% on duration depending on trial phase. Having access to and leveraging electronic health records was estimated to save 1-15% on costs and 1-13% on duration, while patient registries were estimated to save between 4 and 8% of costs and 5-8% on time.

Tech Regeneron has access to now could make their trials and their preclinical work much less costly than the work done by other companies and groups. While these edges may not be huge on their own, they are something, and when we’re talking proportions of trial costs, these small improvements translate to very meaningful sums in the millions of dollars.

Regeneron could even provide access to their data and profit from the discoveries that others make for them, if they so desired. Scholars are, after all, more after status than they are money, and for many of them, being able to say they made a discovery is more valuable than the sums they might be able to receive if they were the discovery’s owner.

Let’s go over a sliver of what Regeneron gains from this deal.

Regeneron gains drug target prioritization capabilities, drug discovery resources, and a phenotyping platform. These are highly sought after prizes in the field, and they are even being pursued by other companies that are less forward-thinking than Regeneron.

Regeneron gains drug target toxicity prediction capabilities, drug repurposing capabilities, and a side effect treatment discovery modality. Regeneron also gains the ability to directly lower costs associated with preclinical and clinical work in other ways thanks to the acquisition of their new data collection platform and all the attached data.

In short, Regeneron gains exclusive access to tools for pharmaceutical R&D acceleration at an opportune time. These tools are key parts of the future of pharmaceutical R&D and the industry already knows it. If Regeneron uses them well, they will quickly become the most valuable pharmaceutical company.

Though I’ve skipped over a lot of detail and I’ve left most of my thesis unsaid, I hope that what I’ve provided you here is enough for you to understand why I predicted that Regeneron would buy 23andMe some five odd years ago.

When someone picks up low-hanging fruit, someone else will come along and ask: if it was so obvious, why wasn’t anyone already doing it? The answer to this is not always that actions are only obvious in hindsight, because often enough, people genuinely do see what to do long before it’s actually done.

The history of the discovery of various drugs is a testament to this: so many advances, from RNA vaccines to GLP-1s, languished in obscurity for a long time. Sometimes drugs were dismissed on the basis of poor negative evidence, and other times, the possibilities for various drugs weren’t ever going to be reached with a given indication, but another one was sitting there waiting to be used. (The Roivant business model is all about that.) There really is a lot of low-hanging fruit.

The truth is, lots of people have been trying to do what Regeneron is going to do with 23andMe. You can see this in the form of various pharmaceutical companies contributing to sequencing charities and other efforts—often for rare diseases, but sometimes for common conditions, too. They contribute funds and occasionally manpower and they get back data, but it’s still hard to develop the whole pipeline for and from that data, which is gathered slowly, to get a product that makes a return.

But 23andMe solves this issue by being dual-use. People sign up for 23andMe to access generally vague health information, to learn about their ancestry, and to connect with their family members. Great! We can use their data obtained for that reason to do so much more. 23andMe’s dual-use nature has resulted in them gathering far more than all other industry genotyping and sequencing efforts.

That data will be used. 23andMe’s low-hanging fruit will be harvested, by Regeneron.

.png)