You’re standing at a specialty coffee shop counter. The barista—probably with an art degree and definitely with opinions about extraction time—slides your latte across reclaimed wood. $4.50. It seems expensive. But to who?

You reach for your card, and here’s the thing: in the three minutes it took to make your drink, that barista just earned more money than the farmer who grew your coffee will make from an entire pound of beans. Not per hour. Not per day. Per pound.

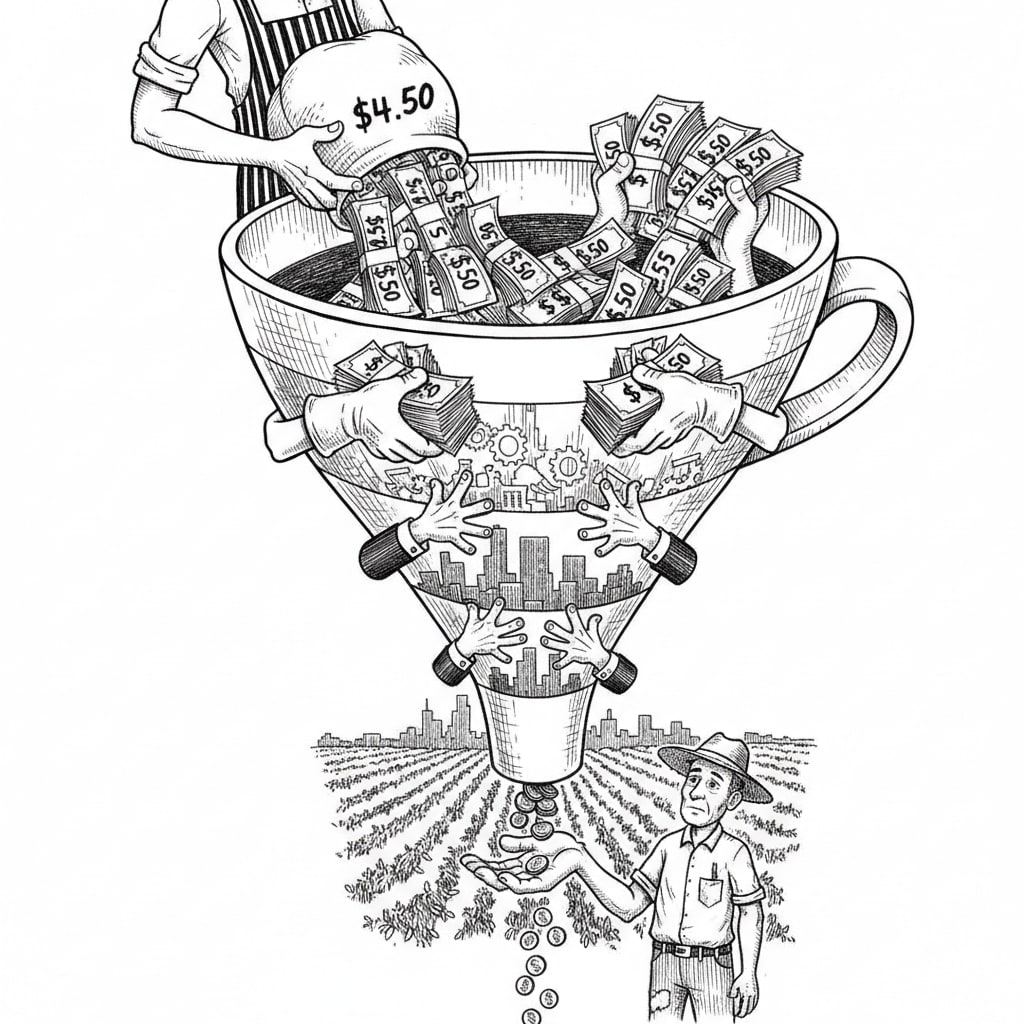

By the end of this, you’ll understand exactly where your money goes, why farmers capture less than 3% of what you just paid, and why that’s not an accident. It’s architecture.

Let me show you the map.

Here’s what most people don’t understand about your local coffee shop: it’s not really selling coffee. It’s selling labor, rent, and milk with a side of caffeine.

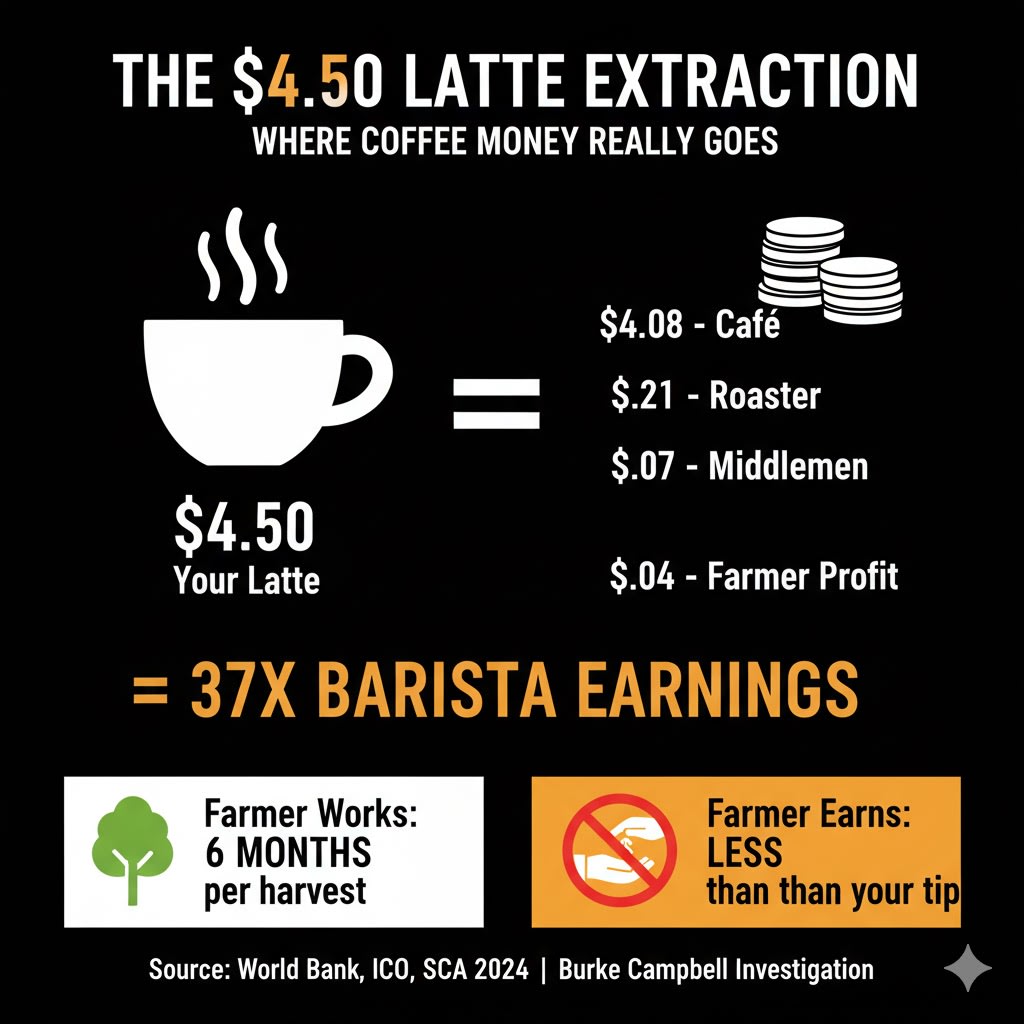

That $4.50 you just paid? Before we even talk about farmers or supply chains, $3.14 of it—70% of your money—never leaves your city. The breakdown is ruthless in its clarity:

Your barista, working at a blended rate of about $20 per hour (wages plus employer costs), just captured $1.00 in direct labor costs for those three minutes of work. Add the tip you hopefully left—let’s say 15%, split among the team—and the barista system pulls another $0.67. Total barista capture: $1.67 per drink.

The café itself needs another $1.90 just to keep the lights on. Rent in any decent urban location runs 10-15% of revenue. Equipment depreciation, insurance, utilities—it adds up fast. The milk in your latte? That costs more than the coffee: $0.36 for the milk versus $0.44 for the actual roasted coffee. The cup, lid, and sleeve run another $0.30.

Here’s the kicker: after all expenses, the café owner clears about $0.54 in actual profit. That’s a 12% margin, which in restaurant terms is actually pretty good. They’re not getting rich—they’re paying rent.

The roaster who sold beans to your café? They charged about $10 per pound wholesale, which works out to $0.44 of roasted coffee in your drink. The roaster keeps about half of that as gross margin—they need it to cover their own equipment, rent, and salaries.

By the time your latte hits the counter, approximately $4.00 of your $4.50 has been captured by operations in your country. We haven’t even talked about the farmer yet.

“Okay,” you’re thinking, “so where does the other fifty cents go?”

Let’s follow it backwards.

Between your local roaster and the farmer exists a supply chain so convoluted it seems designed to confuse. It’s not. It’s designed to extract.

The roaster paid $4.50 per pound for specialty-grade green coffee. Seems reasonable, right? Premium product, premium price. But watch what happens to that money as it moves backward through the chain.

First, the importer takes their cut. Companies like Olam, ECOM, and Volcafe don’t just move coffee—they provide the infrastructure that makes global trade possible. They handle customs, warehouse inventory, manage currency risk, and provide financing. For this, they take about $0.10 per pound. Not much, you think. Until you realize they move billions of pounds. This is wealth accumulation through volume.

Before the importer, there’s the exporter—often the same company, just wearing a different hat at origin. They take 15-25% of what farmers receive. They run the dry mills, manage export licenses, arrange shipping. Another layer, another cut.

The processor who turned coffee cherries into green beans? Add another 5-10%. The cooperative that aggregated small farmer lots into container-sized shipments? There’s 5-15% in “administrative overhead.”

Here’s the devastating math: By the time green coffee reaches your local roaster at $4.50 per pound, the farmer has received somewhere between $2.00 and $2.80. The other $1.70 to $2.50? Absorbed by the supply chain.

But even that $2.80 isn’t profit—it’s gross payment. The farmer’s actual costs—labor, inputs, land—run about $1.80 per pound. Their net profit? Maybe $1.00 per pound. If they’re lucky.

From your $4.50 latte, the farmer’s profit is $0.044.

Four cents. Not four dollars. Four cents.

“Why don’t farmers just bypass the middlemen?”

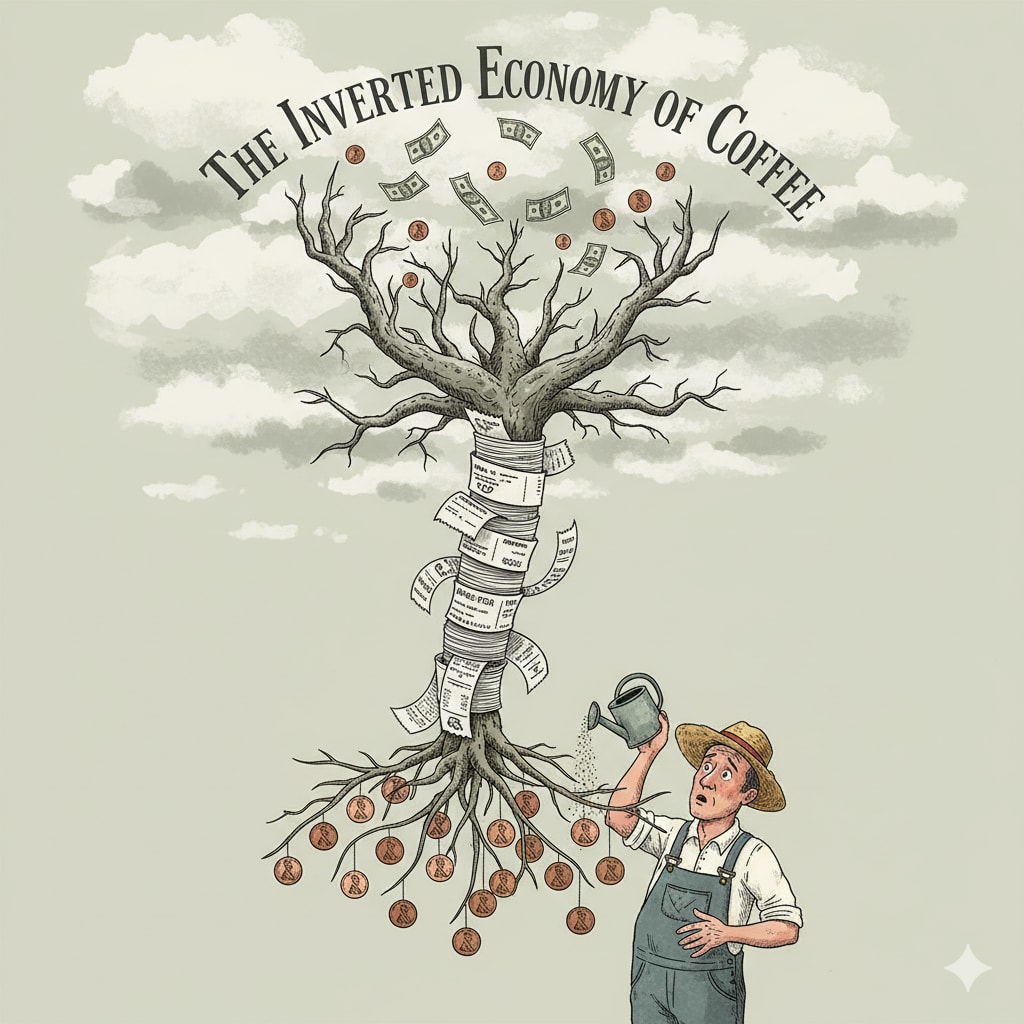

This is where the system reveals its genius. It’s not inefficient. It’s precisely calibrated to prevent farmers from escaping it.

First, infrastructure. A wet mill—the machinery needed to process coffee cherries into beans—starts at $50,000 for basic equipment. Industrial-scale operations run into the hundreds of thousands. A moisture meter for quality control? $2,000. Drying beds? Storage facilities that prevent mold? Cupping lab for quality assessment? The capital requirements stack up fast.

But machinery is just the beginning. The real trap is financing.

Coffee farmers in Honduras, where I’ve worked for 17 years, face interest rates of 18-36% annually for pre-harvest loans. Not 3.6%. Thirty-six percent. Banks won’t lend to smallholders—no collateral beyond the land they can’t afford to lose. So farmers turn to informal lenders or, more commonly, to the very exporters buying their coffee.

Here’s how the trap works: Exporter offers credit at harvest time when farmers are desperate. Farmer takes loan. Farmer now must sell to that exporter at whatever price is offered. The debt cycle becomes the extraction mechanism.

Then there’s scale. A shipping container holds 42,300 pounds of coffee. A typical smallholder produces maybe 2,000 pounds. You need 20 farmers just to fill one container. Someone has to aggregate, coordinate, manage quality consistency across all those farms. That someone is the exporter, and they charge for it.

Export requirements? You need licenses, phytosanitary certificates, International Coffee Organization certificates. Each costs money, requires expertise, demands relationships with government officials. Direct trade sounds nice until you realize it requires navigating bureaucracy in multiple languages across multiple countries.

Payment terms deliver the final blow. Local buyers pay cash immediately. International buyers? 60 to 180 days. Six months. A farmer living harvest to harvest can’t float six months of expenses waiting for payment.

The infrastructure isn’t inadequate. It’s perfectly designed. Every barrier reinforces dependency on intermediaries who extract value at each step.

This isn’t a market. It’s a designed dependency.

Let me show you exactly where your money went:

At the Café:

Barista labor (wages + tips): $1.67 (37.1%)

Non-coffee inputs (milk, cup, syrup): $0.97 (21.6%)

Overhead (rent, utilities): $0.90 (20.0%)

Café profit: $0.54 (11.9%)

Café Total: $4.08 (90.6%)

At the Roaster:

Operations and profit: $0.21 (4.7%)

In the Supply Chain:

Importer logistics: $0.02 (0.5%)

Exporter/processor: $0.05 (1.2%)

At the Farm:

Farmer’s costs: $0.08 (1.8%)

Farmer’s profit: $0.04 (1.0%)

Farmer Total: $0.12 (2.7%)

Read that again. The farmer who grew your coffee for six to nine months captured 2.7% of what you paid. The barista who spent three minutes making your drink captured 37.1%.

Your barista made more from one latte than the farmer made from a pound of coffee.

Actually, let me be more precise: Your barista made 37 times more from your single drink than the farmer netted from the raw material inside it.

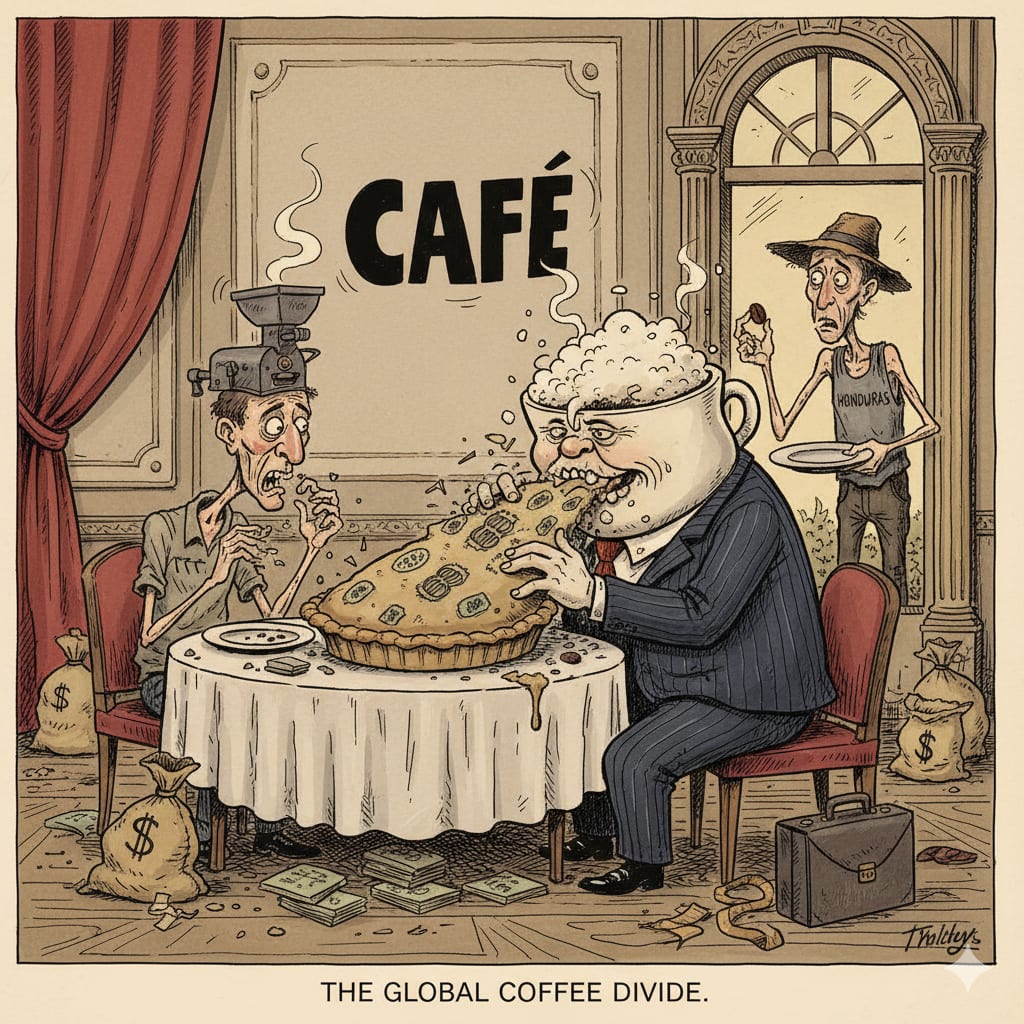

We call this “the market.” We should call it what it is: extraction.

“Just pay farmers more,” people say. “Buy Fair Trade.”

Let me tell you about Fair Trade. The current Fair Trade minimum price is $1.80 per pound, plus a $0.30 premium. Sounds good, right? Here’s what they don’t advertise: administrative costs consume most of that premium. Studies show only “a few percent” of the Fair Trade premium paid by consumers actually reaches farmers. A few percent.

Worse, farmers can only sell 20-42% of their Fair Trade certified coffee at Fair Trade prices. The rest? Goes to the commodity market anyway. They pay for certification, follow all the rules, and still have to sell most of their harvest at regular prices.

Even if farmers could sell everything at premium prices, it wouldn’t solve the structural problem. They still don’t control:

Processing infrastructure (mills, warehouses)

Export logistics (containers, shipping, customs)

Market access (buyers, contracts, payment terms)

Financing (credit, working capital)

Paying farmers more doesn’t change the fact that value is systematically captured by infrastructure owned elsewhere. It’s like giving someone a raise while they’re paying 36% interest on their debt. The raise gets absorbed by the system designed to extract it.

The solution isn’t charity. It’s infrastructure ownership at origin.

What if farmers owned the mills? What if cooperatives could bypass exporters? What if Honduras roasted its own coffee instead of shipping green beans for others to add value?

These aren’t hypothetical questions. Rwanda is building roasting facilities. Ethiopia is developing its own brands. Yemen—where I also work—is creating direct auction systems that bypass traditional exporters entirely.

The extraction architecture isn’t permanent. But dismantling it requires more than consumer choices. It requires producers taking control of the means of production. The real means—the infrastructure that turns crops into commodities into products.

You paid $4.50 for a latte. The farmer got $0.12. This isn’t because your café is evil or your roaster is greedy. It’s because the entire supply chain is structured to ensure value is captured in consuming countries while risk and cost remain at origin.

I’ve spent 17 years watching this system operate from inside Honduras’s coffee industry. I’ve written two books documenting how this extraction engine works. This is not about bad people making selfish choices. This is about infrastructure designed to separate labor from profit.

The map I’ve shown you isn’t a bug in the system. The map IS the system. Every step is precisely calibrated to ensure that those who work the hardest—farmers laboring in mountain fields—capture the least value, while those closest to the point of sale capture the most.

Your barista made $1.67 from your latte. The farmer made $0.04 in profit. That ratio—42 to 1—is the real price of your morning coffee.

This is what we call the free market. But for farmers, nothing about it is free.

Burke Campbell has worked in Honduras’s coffee industry for 17 years and serves as Technical Advisor to Yemen’s Mokha Story auction house. He’s the author of “The Extraction Engine” and “The Extraction Manual,” investigations into the coffee industry’s systematic extraction of value from producing countries. This is what he does—map the architecture of extraction. Subscribe to follow where power actually lives in global supply chains.

.png)