Derek Thompson’s recent essay, “The End of Thinking,” states the problem faced by educators today more clearly than anything else I’ve read.

“I am much more concerned about the decline of today’s thinking people than I am about the rise of tomorrow’s thinking machines,” Thompson writes.

He continues:

The demise of writing matters, because writing is not a second thing that happens after thinking. The act of writing is an act of thinking. This is as true for professionals as it is for students… If reading and writing “rewired” the logic engine of the human brain, the decline of reading and writing are unwiring our cognitive superpower at the very moment that a greater machine appears to be on the horizon.

Thompson’s piece is an essay in the original sense of the term, developing an idea from a standpoint of uncertainty and exploration, and looping in the author’s own life rather than claiming some omniscient perspective.[1] I am assigning it to my students because it’s a model of how I think human-created writing will persist in an age of AI slop: grounded in a personal perspective, concrete, and based in conversations and experience in the world — as well as wide reading in physical books — not just internet searches.

My experiences in the classroom back up the charts Thompson supplies. The shift has been evident to anyone teaching over the past few years: students are massively distracted. Based on my conversations with colleagues, it is now standard practice to scale back the page counts of assigned readings by as much as half when compared to a decade ago.

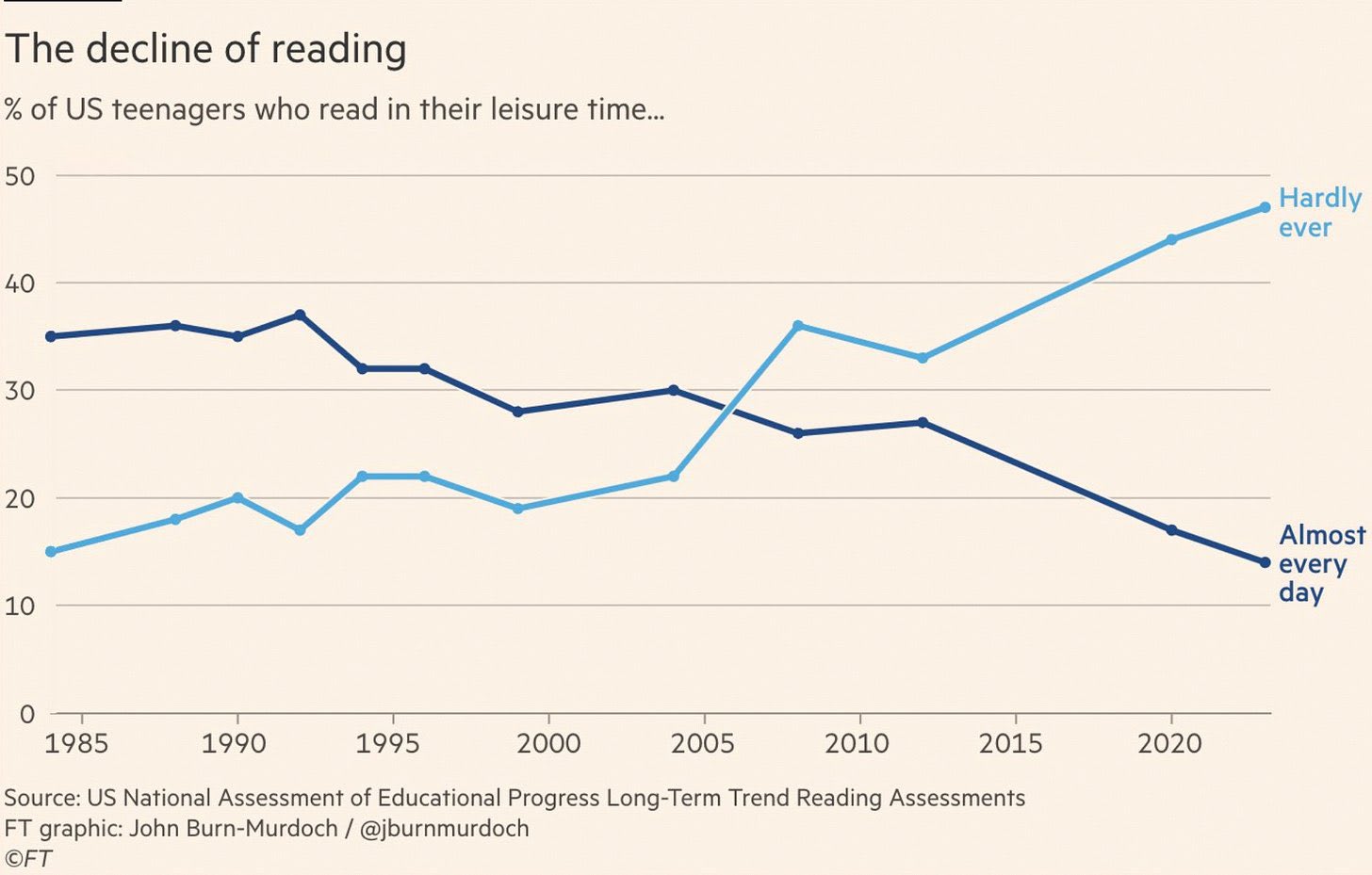

And it’s not just that students are posting lower scores on tests of reading. They are also just reading fewer books in general, both in school and outside of the classroom. The proportion of American teenagers who report “hardly ever” reading for fun is fast approaching 50%, having more than doubled in the past two decades.

As a historian, though, I think there is one big thing missing from discussions of whether we are witnessing the end books — or really, the age of sustained attention on anything.

“Mass market” books and periodicals were, themselves, once assailed as damaging to mental health, to attention, and to society. .

The decline in reading and attention is not only, or even entirely, a problem caused by AI, because it began before the advent of ChatGPT. It seems to me more plausible to blame the phenomenon that my students like to call brainrot. In other words: influencer culture, memes, clickbait social media, short form video, and, in general, the sort of digital content that optimizes for toddler-length attention spans. This can certainly include AI slop — but it is not synonymous with it.

You can see this in the charts: the inflection point for the downturn in test scores is mostly in the 2015-20 period. This was the first generation of young minds fully immersed, from childhood onwards, in data-driven algorithmic feeds intentionally designed to hijack attention. Crucially, it was in this five year period that the algorithmic world fully invaded schools themselves — when students moved from physical books and long-form reading to tablet and Chromebook-based assessments designed not to prioritize long-form reading.

I am not alone in feeling that students who came of age at this time have been harmed, cognitively, by that combination of brainrot outside of school and the loss of a physical connection to classic works of literature in the classroom.

Ironically, however, that very literature was once profoundly controversial. What we now call classic literature was the brainrot of its day — or at least many thought so.

Some examples:

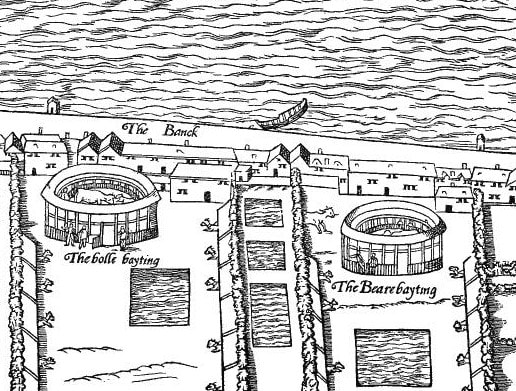

1) The actors and audiences of William Shakespeare’s plays were engaging in an activity that was considered “low-brow” and even unethical by many members of their society. Shakespeare’s theater, The Globe, was ultimately shut down in 1642 in a final win for the long-standing Puritan campaign against drama. One of Shakespeare’s primary competitors, in the battle for Elizabethan attention spans, was the Paris Garden, a rival theater in which bears fought one another to the death, monkeys were strapped to ponies, and fireworks shot money into the crowd. Elizabethan theater, in other words, was decidedly not considered something that was elevating, intellectual, or good for society. It was more like a bad habit.

2) In the 18th century, novels were condemned for harming public morals and intellectual life.

As the literary scholar Gary Kelly writes:

Novel reading was disapproved of in Britain from the seventeenth century at least, but never more so than in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries… The kind of observation found in a book entitled The Evils of Adultery and Prostitution (1792) was not uncommon: “A ... cause of the profligacy of the present age, is that mass of novels and romances which people of all ranks and ages do so greedily devour. This is a new species of entertainment, almost totally unknown to former ages .... The great encouragement given to productions of this kind is a great mark of the frivolousness and effeminacy of the present age.”

The very same novels which are now considered so elevating to young minds — the works of Jane Austen, say, who was 17 when the words above were written — were once bitterly condemned as a cause of societal decline.

They were especially blamed for declining attention spans among young poeple, with regular readers of novels said to be “seldom capable of attending to books where solid instruction is conveyed” and unable “to relish that reading that requires any degree of attention.” Novels were, indeed, a “deadly poison,” especially for young women: “many young girls, from morning to night, hang over this pestiferous reading, to the neglect of industry, health, proper exercise, and to the ruin of body and soul.”

3) By the 1860s and 1870s, women’s literacy, in particular, was being blamed for the technology-induced mental illness epidemic of the day: neurasthenia. We don’t use this word anymore. But in fact, neurasthenia maps rather closely onto the contemporary concept of anxiety and depression induced by social isolation.

What caused it? George Beard, the doctor who coined the term, famously blamed “steam power, the periodical press, the telegraph, the sciences, and the mental activity of women.” Alice James, who suffered from neurasthenia, was urged by her mother to stop reading so much (and keep in mind, she was reading such things as the famously sophisticated novels of her brother, Henry James). Extended reading of any kind was considered detrimental in those who suffered from this malady.

As the above hints at, human nature (and anxiety about human nature) is oddly persistent across the historical record. This is true even in times of massive change in culture, society, and technology. Specific professions, hobbies, and areas of concern rise and fall, of course. But human preoccupations — the sum total of our collective cognition in a given generation or decade — doesn’t seem to me to change much at all. And one of the most recurrent elements of this fixed human nature is the belief in narratives of decline.

In other words: it seems to be in our nature to think that human nature is getting worse. So how do we know when a decline narrative is justified versus when it’s just moral panic?

History suggests we can’t really know — at least not while we’re living through it. What we can control is how we respond.

Thompson ends his essay with a semi-optimistic conclusion, one I agree with:

Culture is backlash, and there is plenty of time for us to resist the undertow of thinking machines and the quiet apocalypse of lazy consumption. I hear the groundswell of this revolution all the time. The most common question I get from parents anxious about the future of their children is: What should my kid study in an age of AI? I don’t know what field any particular student should major in, I say. But I do feel strongly about what skill they should value. It’s the very same skill that I see in decline. It’s the skill of deep thinking.

In fitness, there is a concept called “time under tension.” Take a simple squat, where you hold a weight and lower your hips from a standing position. With the same weight, a person can do a squat in two seconds or ten seconds. The latter is harder but it also builds more muscle. More time is more tension; more pain is more gain.

Thinking benefits from a similar principle of “time under tension.” It is the ability to sit patiently with a group of barely connected or disconnected ideas that allows a thinker to braid them together into something that is combinatorially new.

Culture and technology do not move toward clearly-predictable end points. Instead, they look more like asynchronous pendulum swings. Clearly, the pendulum has swung away from patience, from attention, from sitting with an idea and working hard on it without distractions.

But in the long run, societies don’t simply survive new media technologies passively. They negotiate with them. The eighteenth-century audiences who worried about novels didn’t stop reading them. Instead, they developed new practices for understanding what to get out of them. Eventually, they canonized some novels as “literature” worth sustained attention while consigning most others to oblivion (there are an enormous number of truly bad premodern novels we have all collectively forgotten about).

Likewise, Shakespeare’s plays moved from lowbrow spectacle to classroom staple not because they changed, but because the negative space around them did. The monkeys on ponies rode off into the sunset (or exited, pursued by a bear). Hamlet survived.

My fear today is that in giving in to a sense that this time is different — that this decline is inevitable and irreversible — we will make that prophecy come true.

Our goal must be to deliberately, and flexibly, maintain conditions where sustained attention remains valued. In my classes this year I’m starting with something simple: requiring students to read only physical books, including those which they check out from the library after browsing the shelves on their own. And I’m making an effort to lend them books from my library, whenever they show an interest.

But I’m also allowing them to submit a historically-oriented web app, data visualization, or educational game as an alternative to the traditional history essay at the end of the quarter. I expect most of the submissions will be created with Claude Code and the like, and I’m perfectly fine with that — as long as the code and documentation they submit is motivated by deep thinking about historical events, analysis, and sources.

Is “vibe coding” such things as demanding and instructive as writing essays? Is it a viable alternative to the cognitive labor that goes into traditional research papers? The only honest answer I can give is: we don’t know yet.

People of the past didn’t just survive their new media. They bent it, argued with it, and ultimately made it serve human flourishing. We can do the same.

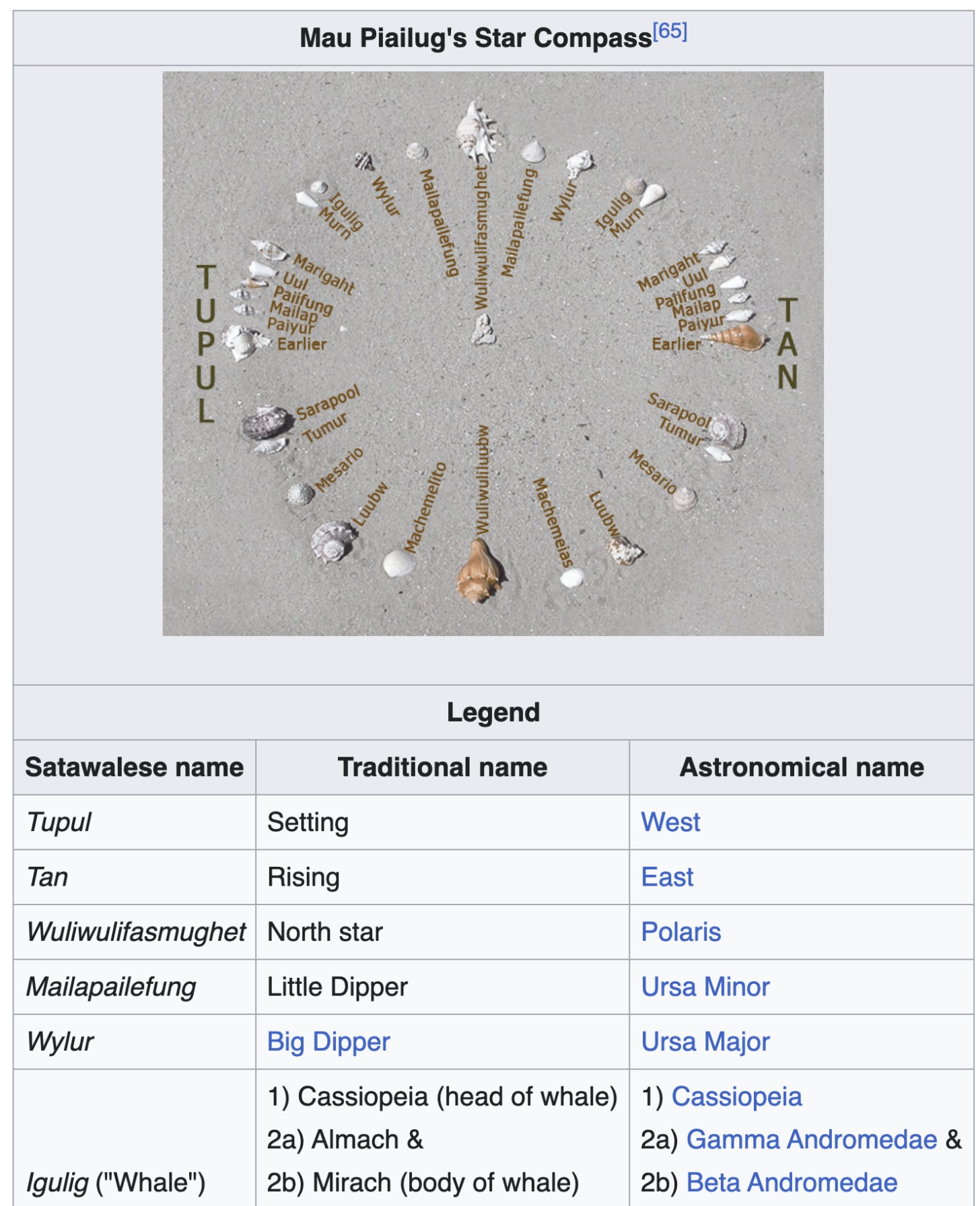

From the Wikipedia page on the traditional Polynesian navigator May Piailug, which is fascinating throughout:

Apart from the bulk of training, which happens at sea, historically boys were taught in the men’s house with pebbles, shells, or pieces of coral, representing stars, laid on the sand in a circular pattern. The bits of shell or coral that are chosen to represent which star or constellation is arbitrary, but generally, larger pieces are used for points of the compass while smaller pieces represent important stars between those points. In Mau’s star compass, these points are not necessarily equidistant. The outer circular formation represents the horizon, with the canoe its center point. The eastern half of the circle depicts reference stars’ rising points on the horizon (tan) while the western half depicts their setting points (tupul). Swell patterns of prevailing trade winds are represented by sticks (not depicted here) overlaying the star compass in the form of a square. All knowledge is retained by memory with the help of dances, chants, and stories, wherein the stars are enumerated as people or characters in the stories.

A fascinating example of non-literate modes of “deep thought.”

Thank you for devoting some of your precious attention to this newsletter. If you’ve made it this far, consider signing up for a paid subscription. This support makes Res Obscura possible.

.png)