The following post is an excerpt from Chapter 8 of Writing for Developers: Blogs That Get Read.

The book explores seven popular engineering blog post patterns:

The bug hunt

We rewrote it in X

How we built it

Lessons learned

Thoughts on trends

Non-markety product perspectives

Benchmarks and test results

The “Bug Hunt” blog post pattern is the programming world’s equivalent of a detective story. It has a theme, a main plot, side plots, a protagonist (you), an antagonist (usually also you, having introduced the bug two weeks ago in the first place). It’s captivating, keeps readers in suspense, and ends with a satisfying plot twist, or a tactical cliffhanger. And the best part is…it’s even more fun to write than to read!

Writing a bug hunting article serves a few purposes, depending on the success of the hunt, where the fault ultimately fell, and a few other factors. Let's tackle the potential purposes one by one.

The fact that a bug appeared and was fixed is undeniably important. But what's way more important is reducing the chance that it happens again – and knowing what to do if it does. While hunting for a bug, it's likely you encountered the following:

A few dead ends

A very convincing red herring

A tool that looked helpful at first, but ended up being unrelated

Another tool that proved immensely useful

Some blog post from 2014 that led you to discover the root cause

All those steps are incredibly useful for the future debugger of another similar issue (likely you again, two weeks older). Awareness of the past dead ends and distractions is especially helpful here. Quick identification of a known red herring can save the future debugger (you) a few hours of unproductive research. You can treat bug hunting blog posts as scrolls of ancient knowledge (two weeks or older), created by your predecessors (you) to pass it on to future generations (also you).

It's give-back-to-the-community time! Chances are, the bug that you fixed doesn't uniquely apply to your project. Instead, it was caused by a sneaky pitfall in your language of choice, one of the libraries, or specific hardware. Your article can genuinely inspire others to think "Huh, we do have exactly the same setup – makes me wonder…" It might also motivate the team behind that technology to consider ways to stop others from making the same mistake.

As a result, writing a story about how you fixed an interesting bug may cause a few other bugs of the same category to be fixed worldwide. It's a superpower! This purpose is especially important if the bug is related to:

Bleeding edge software

Novel hardware

A young open-source community

Those tend to develop dynamically and have very little test coverage compared to industry standards simply because they are too young to be implemented in a critical mass of projects. You can think of this purpose as an external version of the previously described "knowledge dump" – it’s a knowledge dump that you write for everyone, not just for yourself or your team.

Set aside the negative connotation of the “bragging” word. Tech world bragging – at the right dosage – is good for you and your peers. Bragging about doing something interesting, like hunting and resolving a bug, helps you as well as your readers:

It's educational. Your audience can presumably learn something by reading how you achieved your goal.

It broadens your professional network. People intrigued by similar technologies and challenges will likely reach out to you as we outlined in Chapter 1.

It feels good. There’s no shame in acknowledging that attention is one of the benefits of telling the world that you did something.

It yields free criticism – hopefully constructive criticism, but valuable either way. The (often illusory) sense of anonymity on the Internet makes it easy to criticize others, so you can count on lots of comments and nitpicks after your article goes public. But after filtering out the vitriol, you can often learn something new, or even revisit your whole approach to the problem.

Bug hunting is a technical topic, and the audience for bug hunting blog posts is inherently just as technical. Categories of interested readers include:

People with a similar background (which means they are potentially susceptible to introducing or suffering from similar bugs in their systems)

People whose job is finding and fixing production bugs

People in the midst of a similar bug hunt

People who might be able to prevent this class of bug from recurring (those behind the technology where the bug occurred or working on defect prevention tools)

Detective fiction aficionados

Your colleagues

Professional Internet critics specialized in unsolicited advice

It's safe to assume that the audience is someone who:

Already has sufficient professional background to understand the technical terms and idioms you use in the article

If not, is willing to look them up and learn

If not, is absolutely fine with just pretending that they understand it

Therefore, it's fine to treat a bug hunting blog post as one addressed to "intermediate level" (or above) readers and not "newcomers." Advanced technical terms are fine because you're not trying to make the article accessible to the wider public. Just expand any arcane acronyms as you see fit and provide hyperlinks as needed.

Since bugs can occur anywhere, so can bug hunting blog posts. In the wild, you can find bug hunting posts published across a variety of blogs: Big Tech, unicorn, startup, and personal blogs. In general, bug hunting posts published by large high-profile companies are unsurprisingly less common (and more guarded) than those by startups as well as individual contributors writing about open-source contributions and weekend projects.

Here are some prime examples of blog posts that apply the “Bug Hunt” pattern, along with Piotr’s commentary on each.

Author: Michał Chojnowski

Source: ScyllaDB Blog (https://www.scylladb.com/2021/09/28/hunting-a-numa-performance-bug/)

The article describes a performance regression happening on modern hardware with NUMA (Non-Uniform Memory Access) design. The regression seemed to occur randomly on half of the runs, which made it much harder to pinpoint. The article shares a few failed (but nonetheless skillful and impressive) attempts to diagnose the problem. Then, one of the observations leads straight to a breakthrough and a surprisingly small fix – measured with lines of code.

This is the pinnacle of bug hunting blog posts. It’s deeply technical, but at the same time simple to follow. The less experienced readers can skip some of the nitty-gritty details and still learn a lot. All of the failed attempts to diagnose the issue are educational, and surely usable in future debugging.

The casual expertise that the author shows while editing executable binaries directly as if they were text files makes the blog post an extremely enjoyable read. The solution to the problem is also very satisfactory, especially to a programmer’s mind: just one seemingly innocent line of code changed, and all the performance regressions are eliminated.

Author: Amos Wenger

Source: fasterthanlime Blog (https://fasterthanli.me/articles/why-is-my-rust-build-so-slow)

This extensive blog post investigates compilation time issues for a Rust project. It shows multiple techniques for how to profile the compiler itself, decompose the compilation process into manageable pieces, and measure how long each piece takes and why. It's full of images, code snippets, and descriptions of concrete tools you can use. The article's conclusion is not really any single breakthrough, but rather honest advice to apply all the extensive techniques above if you're unsatisfied with your Rust build times.

Compared to an average technical blog post, this one is a hog – in a purely positive sense! It can easily take a skilled reader half an hour to read through it, and it's probably a good idea to digest it in three or four parts, taking breaks from the screen to avoid dizziness and diplopia.

This is a positive trait because it makes the article stand out. Many tech articles try to squeeze as much information as possible into 4 to 6 minutes of reading. And that’s fair, considering the average attention span of a human being raised on smartphones rather than playing outside all day with occasional cartoon breaks. Yet, a long article will appeal to the old school folks who were once capable of reading a book in a single sitting.

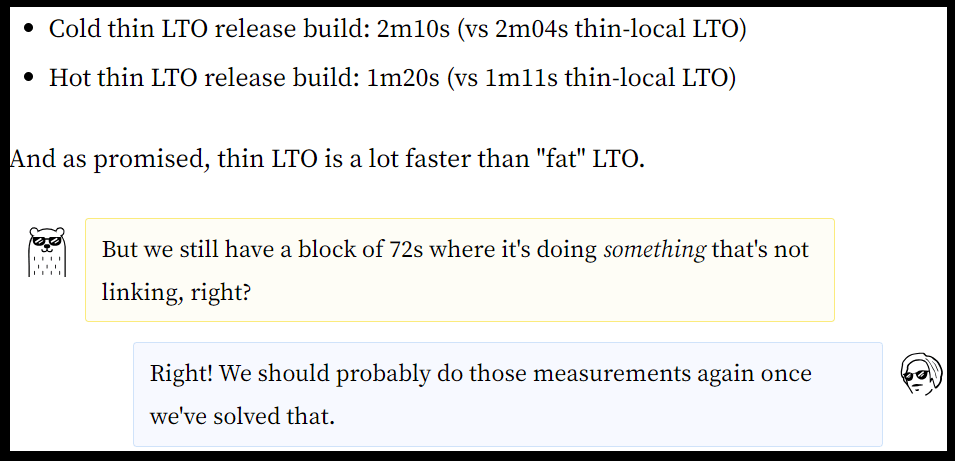

The article has a unique style featuring the author's alter ego, Cool Bear, who regularly adds short humorous comments – keeping the reader engaged throughout the (lengthy) reading process.

Figure 8.1 This article highlights insights from the author’s alter ego, Cool Bear – sometimes in dialog with the author’s own interior monologue.

This type of a bug hunting blog post also serves as an encyclopedia of techniques for debugging the Rust compiler. I have it bookmarked, just in case I ever need to refresh my knowledge of how to measure linking times in my projects. The conclusion is also quite unconventional: instead of building tension and finally presenting readers with a surprise solution, it's simply an honest summary with encouragement to reach out.

Author: Piotr Kołaczkowski

Source: Piotr Kołaczkowski’s Blog (https://pkolaczk.github.io/server-slower-than-a-laptop/)

The blog post describes how local benchmarks detected a bottleneck on machines with lots of CPU cores. The author shares a performance analysis, performs some profiling, then offers a few explanations of how modern CPUs work under the hood and how the processor caches manage memory. The suggested fix is a natural consequence of the conclusions reached earlier in the article: minimizing the amount of state shared between processor units eliminates the bottleneck.

This is another stellar example of a bug hunting blog post. Its title is a little clickbaity, but still elegant enough to avoid being rejected by the average ad-blocking software. The technical details are much more universally understood than the ones in Chojnowski’s NUMA blog post (described earlier in this section).

The article is sneakily educational, digressing on things like "How many nanoseconds does L3 cache access take on average on Intel Xeon." That's great practice; it leaves those details imprinted in readers' minds without them realizing it. Who knows – maybe one day that tucked-away tip might help fix a performance bug in another project. Overall, the article leaves readers satisfied with the result, and also a tiny bit smarter in the field of CPU architecture and performance.

Author: Sanchay Javeria

Source: Pinterest Engineering Blog (https://medium.com/pinterest-engineering/lessons-from-debugging-a-tricky-direct-memory-leak-f638c722d9f2)

Pinterest's development team shares their experience hunting a stream processing code memory leak that led to cascading failures in their distributed system. It goes over debugging techniques for the Java environment and then finally pinpoints a bug in application code that caused the memory leak.

This is a classic bug hunting article – so much so that it could be used as a blog post template for hunting down almost any issue in Java code. It contains the customary investigation steps, along with screenshots from observability tools. Also following custom, the culmination paragraph is called "The Fix." It explains that the culprit was yet another memory leak issue caused indirectly by garbage collection mechanisms in Java. Hint: It always is!

In this context, the conclusion isn't really an earth-shattering breakthrough, but it definitely meets the readers' expectations. I bet the majority of the readers think "Ah, I knew it from the start" right after learning the root cause.

Author: Brendan Gregg

Source: Brendan Gregg’s Blog (https://www.brendangregg.com/blog/2021-09-06/zfs-is-mysteriously-eating-my-cpu.html)

The blog post describes a hunt for the cause of mysterious higher-than-expected CPU usage. It shows how to narrow the candidates down to a single function call with analysis tools and concludes with a surprising performance bug in ZFS – a file system implementation.

The title itself is captivating, but then something in the URL jumps out at you: it's by Brendan Gregg, the flame graph inventor! This is a prime example of why personal brand matters so much. When I see “Brendan Gregg,” I immediately assume that the article is interesting … and I wasn't mistaken in the slightest.

Given Gregg’s expertise, the problem analysis naturally involved flame graphs. The root cause is quite a surprise, and Gregg described it in a very informal and funny manner. The blog post is also very concise: a three-minute read, even if you reserve some time upfront to look at the flame graph screenshots. It clearly shows that you don't need to write thousands of words to squeeze in lots of knowledge, tips, and interesting technical details.

Bug Hunt blog posts can vary as wildly as the actual bug hunts – but they tend to share the following characteristics:

They recount the story chronologically, from the moment the evil bug manifested itself, to when it was pronounced dead

They focus primarily on the thrill (and pain) of the hunt

They freely share the evidence collected along the hunt so readers can put on their detective hats and play along

They’re largely geared to experienced developers who know the technologies being discussed (or are ready to learn as they go)

They offer technical nuggets that could be interesting now, lifesaving later

Let’s examine each in turn.

Bug hunting blog posts often follow a specific structure since they are the technological equivalent of detective stories. (If you want an intro or refresher on the structure of a detective story, generative AI does a decent job here). The introduction paragraph does not reveal too many details and certainly does not provide a spoiler on the solution. Often, they just elaborate on the (properly mysterious) title with a few more words.

Once the problem is defined, the hunt begins, usually with a few failed (but educational) attempts. The tension builds until the author reaches their aha moment, which is followed by the fix description (and that section is customarily titled "The Fix"). After the solution is revealed, the blog post concludes by describing preventive measures to stop this bug from recurring – and often a concise apology to any affected users.

The meatiest part of the article is the path towards identifying the issue. Spending around 80% of the post explaining the investigation process is a good rule of thumb. For example, here’s how much time each of the example blog posts above spent on the investigation (based on word count):

Chojnowski: 85% hunt

Wenger: 83% hunt

Kołaczkowski: 83% hunt

Javeria: 82% hunt

Gregg: 93% hunt

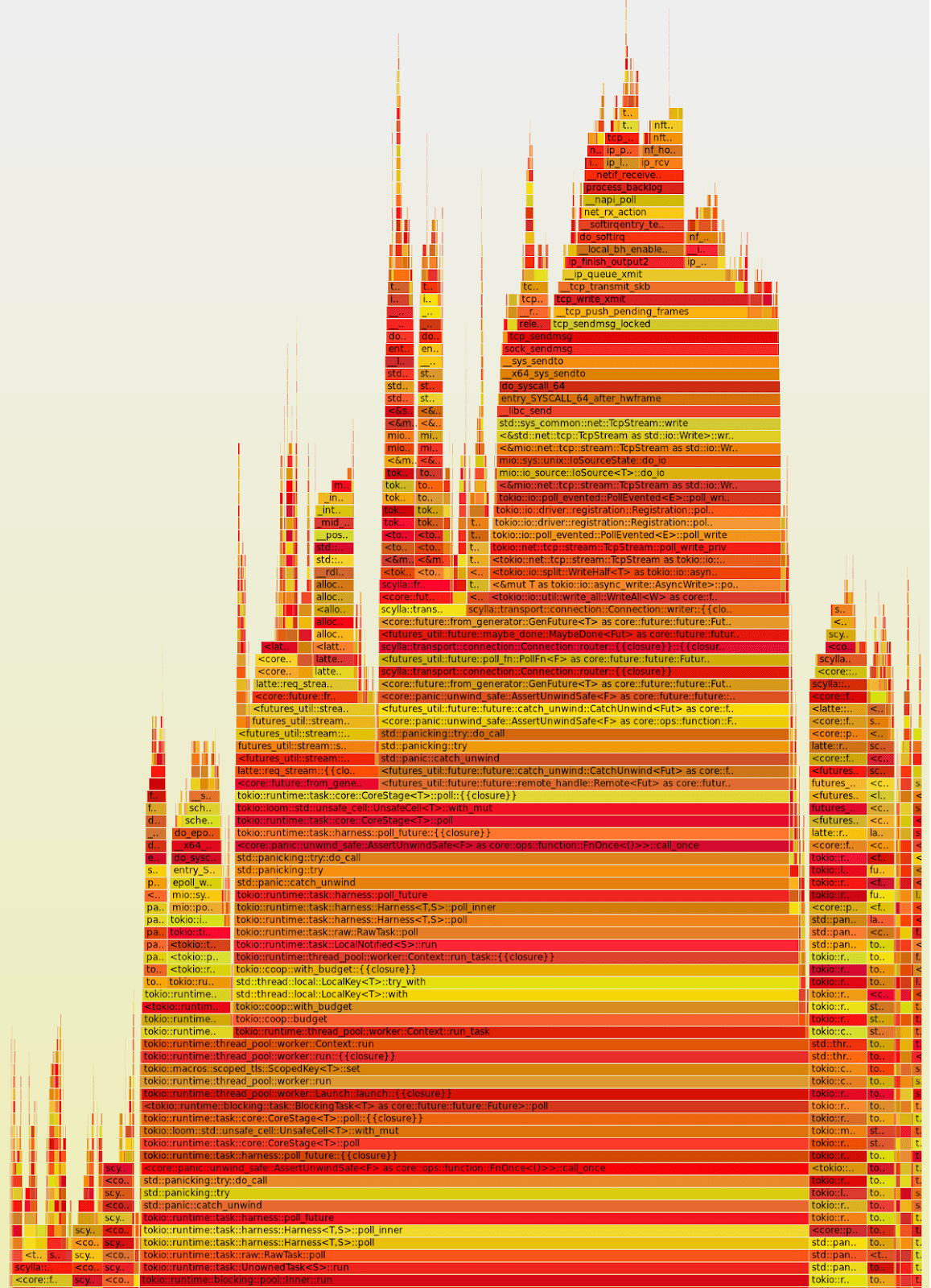

Bug hunt blog posts are usually full of forensic evidence. Readers want to see flame graphs, numbers, charts, scripts, and code samples. This lets them step into your detective shoes and try to figure out the riddle before the big reveal.

For example, here’s some of the evidence shown in the example blog posts:

Chojnowski: Database monitoring graphs (writes per shard), network and disk performance graphs, CPU stats, flame graphs and instruction-level breakdowns, the CPU’s performance measuring monitoring unit (PMU) events, and a variety of attempted code fixes

Wenger: Cargo build timings, a timeline of compilation units, CPU usage and concurrency graphs, debug information, flame graphs, tracing through Chromium and Perfetto, attempted code fixes, dependency graphs

Kołaczkowski: A look at the benchmarking tool’s design, throughput results (on his 4-core laptop vs. a 24-core server), flame graphs

Javeria: Out-of-memory error details, backpressure tests, and multiple forays into memory monitoring

Gregg: Flame graphs (of course!), ZFS mount details, arcstats, and all the source code, via a GitHub link

Figure 8.2 Example of an eye-catching flame graph. You can interact with this flame graph at https://scyllabook.sarna.dev/perf/fg-before.svg

Flame graphs are particularly common across bug hunting blog posts. They offer a great way to visualize your debugging and performance profiling process. And they’re interactive – users can zoom in to the interesting parts, filter out only the events that match a particular regular expression, and much more. Flame graphs can be created from the output of popular tools, such as Linux's perf profiler or Rust's cargo flame graph command.

Bug hunting articles tend to be expert friendly. The author usually assumes that the audience is proficient (or at least familiar) with the technological stack used in the article. Code samples and scripts shared in the article are typically targeted to readers who are familiar with the programming languages used. These types of posts aren’t conducive to basic explanations of core language concepts; if the reader doesn’t “get it,” they might need to soldier through it or just move on.

This is distinctly different than in other blog post patterns, such as “We Rewrote It in X” (discussed in Chapter 9). Blog posts in that pattern are more appropriate for those just getting started with the given technology and often include an “Introduction to the New Language” section.

Blog posts following this pattern can be quite educational for developers beyond the impacted team. The meaty part, bug identification, is abundant in details about how to inspect similar issues. Even more importantly, these sections are abundant in reproducible details: ones that are likely to be useful for solving all kinds of similar problems that readers might face in the future. The blog post serves its purpose if it leaves the reader equipped with a few more tricks they can apply, just in case they ever encounter a similar bug at some point in their life.

For example, here’s a high-level view of what readers could learn from each of our example blog posts:

Chojnowski: The kinds of issues you might encounter with complex memory architecture (NUMA), especially with ARM processors

Wenger: Ways to improve your Rust build times

Kołaczkowski: How modern CPUs work under the hood and how the processor caches manage memory

Javeria: Java is evil

Gregg: How to apply analysis tools like an absolute expert

The best blog posts are born from the most torturous bug hunts. Driven by the glorious feeling of finally solving the mystery, strike while the iron is hot. Write your impressions before the high of the hunt wears off and help your peers solve their next case faster.

Here are some tips for writing your own Bug Hunt blog post.

This is especially important if you hunted a bug that had a notable impact on users – or if the disclosure of this bug could negatively impact your company’s reputation and/or the all-important stock price. Open-source or source-available projects usually don’t impose any legal considerations (except maybe trying to avoid getting your code infected with one of the GPL licenses and its "copyleft" terms). Not all code is open-source though.

Before you publish code snippets of your heavily guarded corporate secrets, make sure that your boss and any interested parties are fine with it. Even if you skip the code, your superiors still may be averse to making certain information public, especially if the bug was related to security, or ended with an unfortunate data leak. Use this rule of thumb: Ask first, write and publish later.

Technical details are a must in any, well, technical blog post. If your article lacks details like code samples, specs on the exact technology used, step-by-step instructions, etc., many readers will leave unsatisfied. Even worse, they might doubt your integrity. Perhaps the inconvenient bits were deliberately omitted to make the product look better? If you worry that you might be adding too many technical details, err on the side of more. Readers can always skip over them if they don't find them interesting.

Bug hunting blog posts are especially expected to be loaded with tips, tricks, code, benchmark results, as well as links to open-source repositories and documentation. Otherwise, you rob readers of the fun opportunity to draw their own conclusions from the copious evidence. As noted earlier, it's fine to be expert-friendly here. You can assume that the audience is either already familiar with the technology described, or willing to catch up (with the help of your blog post).

Your failures and misery provide readers with the cathartic effect that brought them to your blog post in the first place! They also give rise to the most educational aspect of bug hunting articles. After all, it's great to learn from mistakes, but it's even better to learn from somebody else's mistakes first.

Bug hunting blog posts are usually written after the root cause has been identified and the bug fixed. The more pain and suffering are described in the first paragraphs, the better the final breakthrough looks. Readers who struggle with similar issues are going to actively search the Internet for descriptions of similar problems, so all the sorrowful keywords like "broken," "fault," or "FUBAR" serve dual purposes – they're an emotional outlet for the author's frustration, plus they also make the blog post easier to find online.

Don't try to convey a perfect, pristine bug hunt. Dead ends and failed attempts bring in tons of educational value. Programmers (which is of course a synonym for “great minds”) think alike. That means some readers could get stuck in the same dead ends – unless they read your cautionary tale first.

Benchmark results, metrics, and all kinds of numbers are the equivalent of clues and proofs from the detective fiction world. Bug hunting blog posts look less legit if they use vague phrasing like "our system is now much faster." Readers will immediately think "Yeah, but how much faster?" followed by "Dear author, if you were really proud of the results, then you would have posted them…" Screenshots from your metrics (or even better, interactive figures like flame graphs) catch readers' eyes, making the article both more credible and more enjoyable to read.

For most blog posts, we recommend sharing the TL;DR early on so readers can quickly decide if they want to continue. Not here! With bug hunt blog posts, avoid spoilers at all costs! The tension should be patiently built until the aha moment occurs, and the fix is revealed. This is key for allowing readers (those not in a hurry, at least) to vicariously experience the thrill of the hunt, with all its twists and turns. They probably already suspect that the article concludes with a happy ending, because otherwise it wouldn't be published. But aren't most detective stories like that anyway?

That being said, some readers will get impatient. Maybe they drew their own conclusion after just a few paragraphs and want the immediate gratification of confirming that they got it right, right away, unlike silly old you. Maybe this is the twelfth Java bug hunting blog post they’ve come across this month and they want to see if this is yet another one where the garbage collector is ultimately to blame. Be kind and mark “the fix” with a nice prominent heading so they can skip ahead to the smoking gun.

As a bonus, having a clearly labeled fix is also helpful to those who are returning to your blog post because they’re now suffering a similar problem. Back when they were reading this for fun, they enjoyed following along with the thrill of your hunt. But now that the tables have turned, they want to go straight to your fix and see if it will save them in their own moment of despair.

Bug hunt articles can get long, especially if you’re covering every little twist and turn (as you absolutely should!) If you end up writing a blog post that will take over 20 minutes or so to read, consider adding a few clear breaking points for readers, in case they opt to consume your article in more than one sitting.

For example, you could provide a short recap of the progress of the investigation so far. You might add an explicit note that the steps described above led to a dead end, leading to a new thesis. Or you could simply use subheadings like “Phase 3,” subliminally suggesting to the reader that it's fine to take a short coffee break here without losing context.

Readers aren't here to read an official failure report. The captivating bits are the personal story, the struggle, and the final joy of figuring out what was wrong. The best bug hunting blog posts use an informal conversational tone, and anecdotes are very much welcome.

Narrate it from your personal point of view. Don’t hesitate to share what was going through your mind as the mystery unfolded. Also, rants are borderline mandatory and expected – in reasonable doses, of course. Deep down, most humans enjoy reading about other people’s frustrations and feeling the indirect relief that it didn't happen to them (yet).

The “building tension” and “providing full access to clues” approaches detailed above are two fundamental ways to keep readers engaged (yes, they are shamelessly stolen from real detective stories). In addition, you might want to:

Write in an extremely casual tone, sacrificing “proper” grammar as needed to keep it conversational

Create a faux dialog with the reader: ask them questions so they’re encouraged to step back and form their own hypotheses (which you will proceed to confirm or disprove)

Write as if you’re in the thick of the hunt (e.g., “Let’s see if …” vs. “Then we checked if…’’)

Share exactly what popped into your head (no matter how silly it seems in retrospect) as you encountered each new piece of information

Explicitly call out critical moments like “plot twist,” “dead end,” and “the aha moment” to ensure readers are in the right mindset at every point

The most important reason for publicly acknowledging your collaborators is pure kindness. Bug hunts are among the most infuriating parts of computer programming, and misery loves company. Your collaborators probably made the pain a bit less excruciating; if you appreciate that at all, do thank them here. For the not-so-empathetic folks, there are also pragmatic (read: selfish) reasons for thanking your collaborators. Your acknowledgment could make them more likely to assist in the next bug hunt. Also, if you name someone in a blog post, you can pretty much guarantee that they will read it – and maybe they will even share it. And perhaps someone they know will be the person to start it trending on Hacker News.

Feel free to extrapolate from specific errors (e.g., "Our Rust code had a bug") into more general issues (e.g., "Rust standard library makes it easy to deadlock in this particular use case.") Bug hunting blog posts are also opportunities to shine some light on pain points you have with a particular technology. You’ve managed to attract a captive audience, interested in what you have to say. Why not take advantage of that? If you noted something particularly problematic with the language or library you used, bite the bullet and suggest that something should be fixed upstream. Programming language and library maintainers appreciate constructive criticism that helps improve their projects.

Writing a bug hunting article serves to share knowledge, raise awareness about bugs you encountered, and showcase your achievements

A bug hunting blog post targets a technical audience, from experts to enthusiasts, usually assuming (at least) intermediate knowledge of the terminology

Bug hunting blog posts are typically heavy on investigative details, showcasing technical evidence in the form of numbers, benchmarks, results, and graphs

Top tips:

Check for transparency issues

Do a technical deep dive

Be brutally honest

Include numbers and benchmarks

Avoid spoilers

Clearly mark “the fix”

Make it personal

Thank your collaborators

***

You can preview more of the book on the Manning site (don’t miss the foreword by Bryan Cantrill and afterword by Scott Hanselman). Please note that the words get scrambled at some seemingly arbitrary point beyond our control. Sorry! ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

.png)