Here’s a secret nobody seems ready to admit: growth as we knew it is dead. Not dying, not slowing—flatlined. For decades, investors have made easy money riding an expanding population wave. More people meant more workers, more buyers, more borrowers, and a reliable tailwind for basically everything. Economists, businesses, and politicians built their entire careers (and forecasts) on the assumption that this growth would never stop. Surprise! It stopped.

We’ve hit peak babies. Birth rates are collapsing faster than politicians’ promises, people are living way longer, and societies everywhere are graying at warp speed. For the first time in modern history, the global population pyramid—that comforting, broad-based triangle packed with kids at the bottom—is flipping upside down into something that looks suspiciously like a coffin.

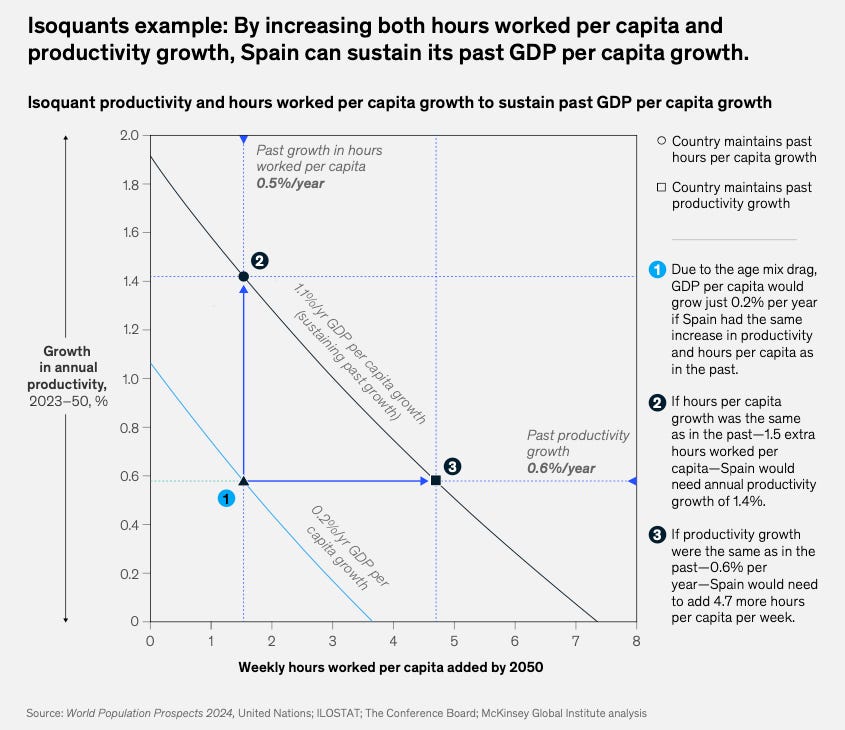

McKinsey recently published a thoughtful, carefully-worded report on what they politely call a “new demographic reality.” Let’s translate: we’re screwed. Unlike McKinsey, I don’t have consulting clients to please, so let’s be blunt: no babies equals no growth. No growth equals an economy where one person’s gain comes at another’s direct expense. Suddenly, the game isn’t about making the pie bigger—it’s about grabbing your slice before someone else does.

Welcome to the zero-sum economy.

For investors, this changes everything. Passive indexing built on endless GDP expansion? Dead strategy walking. Real estate booming forever because, well, everyone needs homes? Tell that to Japan’s ghost towns. Commodities riding a never-ending wave of consumption? Good luck when fewer people means fewer things built, fewer things bought, and fewer mouths to feed.

In short, the investing playbook of the past century just expired. And if you’re still playing by those old rules, you're effectively betting your retirement on the assumption that everyone will suddenly decide to start having kids again—or, better yet, live forever.

Welcome to Edelweiss Capital Research! If you are new here, join us to receive investment analyses, economic pills, and investing frameworks by subscribing below:

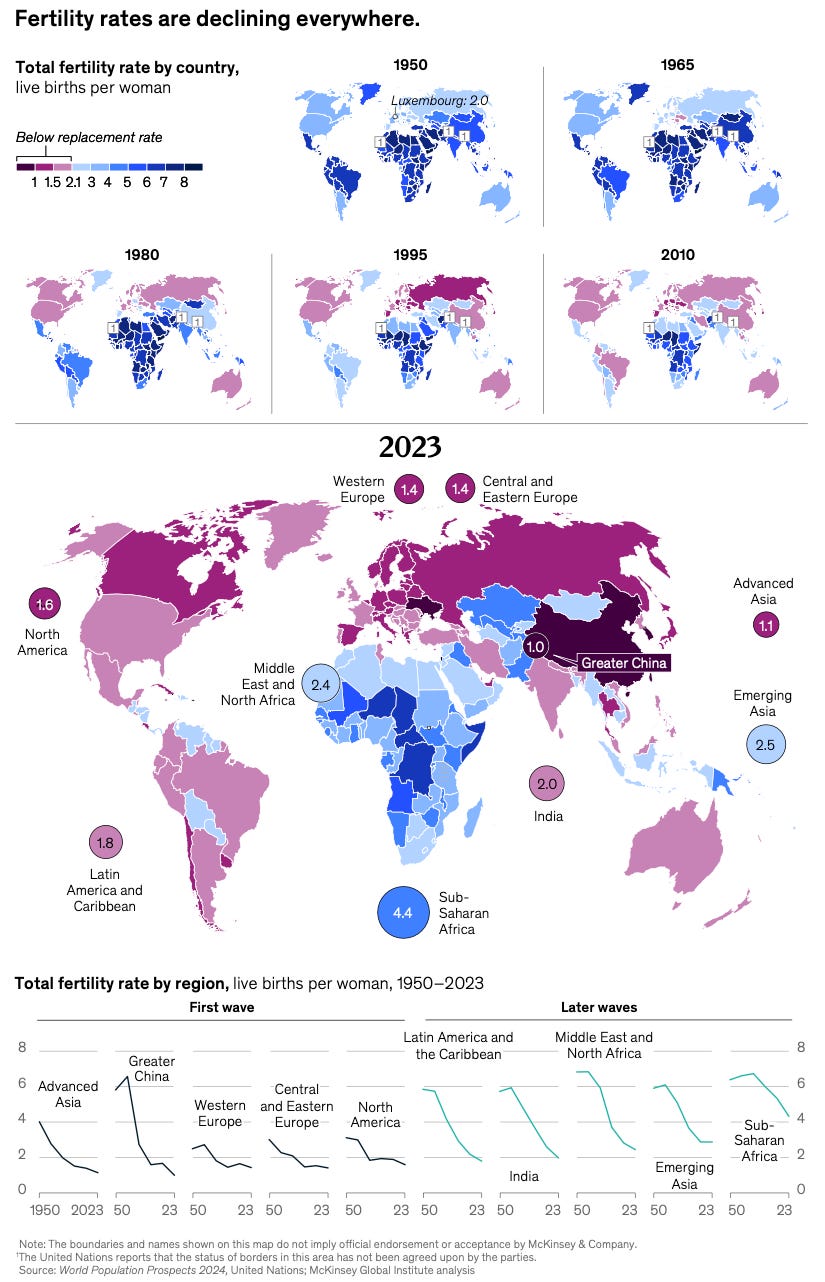

Let’s kick off with something that should terrify any investor paying attention: humanity has basically decided it can’t be bothered making babies anymore. Forget what your grandparents told you—kids aren’t happening, at least not at scale. Two-thirds of humanity now lives in countries where fertility rates have dropped below the magic 2.1 babies per woman needed to maintain the population. Not grow, mind you—just keep things steady. If people were stocks, we'd call this one a screaming short.

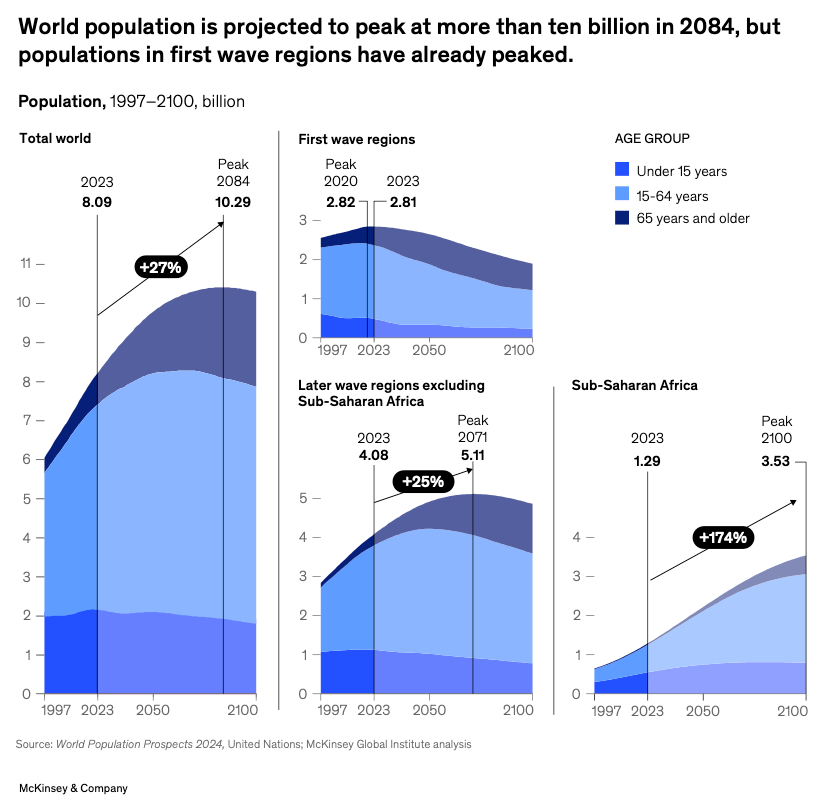

Japan, the global leader in things we don’t want to emulate, peaked years ago and now loses hundreds of thousands of people annually. China, the economic miracle that made all investors dream of infinite growth, finally hit its demographic iceberg in 2022. Its population shrank for the first time since Mao was still on the posters. Europe? Been shrinking for years, just politely quiet about it.

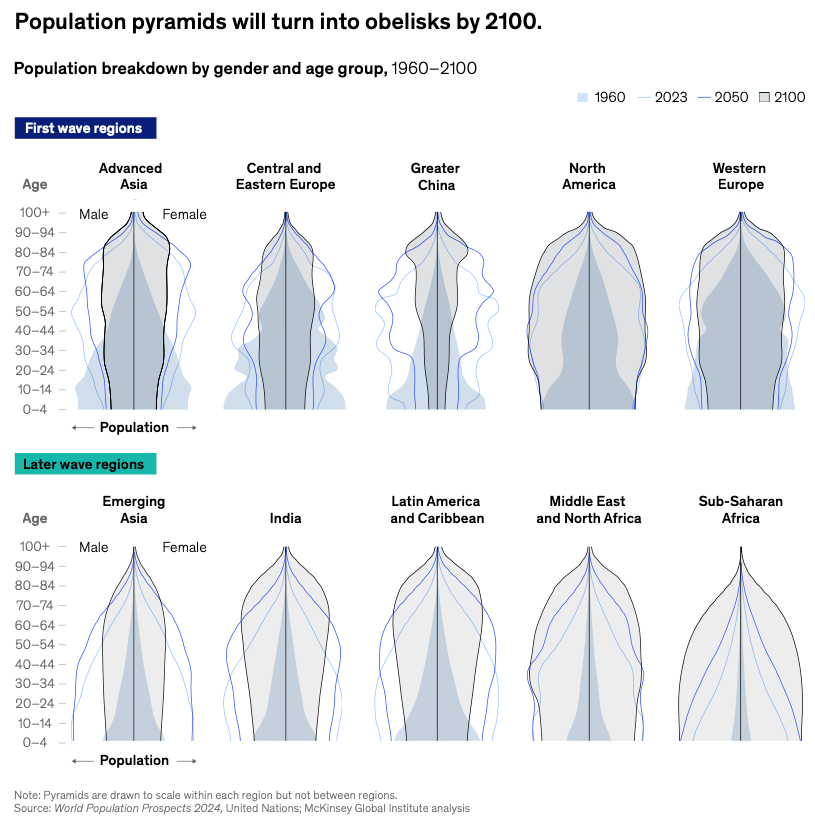

The result isn’t subtle. Remember those neat population pyramids from your high school textbook, fat at the bottom with kids, thinning at the top? Flip that upside down. We’re now building what McKinsey politely calls “obelisks.” Let’s be honest—they look like tombstones. Instead of having lots of young workers funding pensions and healthcare for the elderly, now we have lots of elderly expecting pensions and healthcare from an ever-shrinking pool of workers. It’s the demographic equivalent of a Ponzi scheme running out of new recruits.

Consider these fun numbers: In advanced economies plus China, the share of working-age people (aged 15–64) is already down to 67%. By 2050, it plummets further to 59%. Worldwide, there used to be about 9 workers per retiree in the late ’90s; today it’s closer to 6.5. By mid-century, we’re looking at fewer than 4 workers per retiree globally. In places like Japan or Italy, it’s heading toward 2 workers per retiree. Think about that: two working people to support every retiree’s healthcare, pensions, and social services. If that sounds like a sustainable model to you, I’ve got some Japanese real estate to sell you.

Regions are hitting this demographic wall at different speeds. Japan and Europe are the reluctant trendsetters, but nearly everyone else is headed down the same path. Even India and Latin America—today’s “young” markets—are seeing birth rates plummet, just later and from a higher level. Sub-Saharan Africa might dodge the bullet for a while, but betting your portfolio on Africa’s demographic dividend paying your pension feels... optimistic.

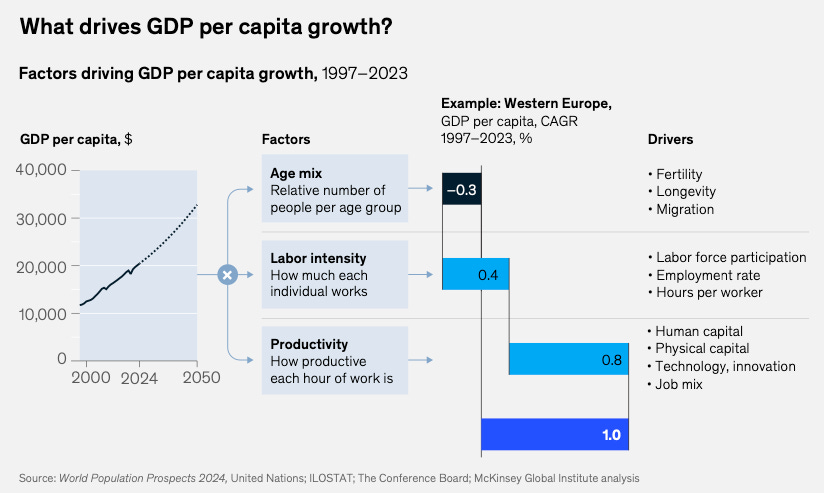

Why does this matter for investors? Simple. Our entire economic system—business forecasts, government budgets, investment returns—is predicated on population growth. More people have always meant more consumers, more production, more GDP. It was practically automatic. But now the baby-making machine has broken down, and population growth isn’t a given—it’s over. If productivity doesn’t skyrocket, growth stalls out. And without growth, the economy stops being a positive-sum game where everyone can win. Suddenly it’s zero-sum: my gain becomes your loss.

Welcome to the new economic reality, investors. The demographic boom is done, and nobody’s really figured out what comes next. But at least we’re all getting older together.

If demographics were a horror movie, government bonds would be the naïve teenager who goes downstairs alone to investigate a strange noise. Bonds depend on governments being able to reliably tax a steadily growing workforce to fund pensions, healthcare, and the thousand other goodies aging voters demand. But guess what? That workforce is vanishing. Fewer workers, fewer taxpayers, ballooning healthcare bills. You can probably see where this is headed.

If you want a preview, look at Japan—once again, our grim glimpse of everyone else’s future. A quarter of Japan’s citizens are over 65, and that number is rising faster than a Bitcoin meme-stock combo. Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio now hovers comfortably above 250%. And remember: Japan has had years of near-zero rates and deflation—imagine what happens if inflation ever does kick in (as it is happening right now).

Other developed countries are on the same road. Europe? Same demographic doom-loop, just behind Japan by a few years. The US? Slightly younger, but the entitlement spending train has left the station and it’s not coming back empty-handed.

How does this play out? Maybe governments just borrow forever, hoping investors stay gullible indefinitely. Maybe they print money like there’s no tomorrow (because there might not be, at least fiscally speaking). Or maybe austerity hits and elderly voters who still show up at the polls make life politically impossible. In weaker economies, it might even mean defaults or severe haircuts for bondholders. Good luck betting your portfolio on that stability.

Of course, bond bulls comfort themselves with dreams of eternally low inflation and near-zero interest rates. But betting that governments can issue infinite amounts of debt forever without markets waking up one day and deciding it’s too risky—that’s not investing. That’s wishful thinking.

Real estate investors have enjoyed one hell of a ride. The assumption was simple: populations grow, people need homes, prices go up. Repeat. But what if the people part suddenly disappears?

Take another look at Japan. There are now roughly 9 million empty homes—14% of all houses—scattered across towns slowly turning into ghost villages. You can literally get houses for free, provided you promise to actually live there.

Japan isn’t unique. Southern and Eastern Europe have towns where more cats than kids roam the streets. Even places that are still vibrant today, like parts of Germany or Italy, face a bleak future where fewer young families mean fewer homebuyers. Who’s left to buy the suburban three-bedroom houses when there aren’t any young couples moving out of the city?

What we’ll likely see is a deep split in real estate markets. Urban cores and trendy cities—where jobs, healthcare, and culture cluster—will probably hold and increase even more in value. Apartments and condos designed for older singles or couples will become far more attractive than sprawling McMansions with unused bedrooms. At the same time, suburbs and rural areas will be increasingly abandoned or heavily discounted.

Real estate won’t die everywhere, but the "rising tide lifts all boats" era is done. Now, picking property means figuring out not just what’s attractive today, but who will even be around to want it tomorrow.

Commodities, those raw building blocks of modern civilization, had an easy sell for decades: more people, more stuff, more demand. Easy math. But what if the people don’t show up?

When fewer babies mean fewer people building homes, driving cars, or buying consumer goods, the demand curve doesn’t just flatten—it reverses. Energy, steel, copper, cement—these are materials that feed on growth. Shrinking populations mean less construction, less infrastructure investment, fewer appliances sold, and fewer cars hitting the road.

Sure, you’ll still have cycles and short-term spikes, driven by geopolitics, short-term bottlenecks, or random OPEC tantrums. But structurally? The long-term picture for commodities tied closely to economic expansion looks bleak.

Of course, it won’t be a blanket disaster. Some niche commodities might thrive. Anything catering to seniors—think lithium for medical devices, pharmaceuticals, advanced healthcare products—could actually grow. Higher-end agriculture, like premium foods or supplements favored by an aging population, might hold steady.

But if your commodity strategy was simply “more people means more stuff means higher prices,” it's time to recalibrate. Growth isn’t guaranteed when the world is filling with retirees rather than new consumers. This isn’t the end of commodities altogether—just the end of easy money betting blindly on perpetual population-driven booms.

Here’s a nasty little secret hiding behind decades of comfortable equity returns: companies never needed to be especially brilliant to keep growing. For most businesses, it was enough that populations kept expanding, wages rose steadily, and more consumers appeared year after year, eager to buy whatever they were selling. Management could basically coast—some did, and their stock prices still went up. Good times.

But that autopilot era is done. If your customer base isn’t growing, neither are your revenues, and if your revenues aren’t growing, margins get squeezed. No amount of financial engineering or buybacks can hide that reality forever. The result? A bitter new reality where companies start cannibalizing each other’s market share to survive. Welcome to the zero-sum market.

Passive indexing—the great lazy miracle of the last decade—also hits a wall. You can’t buy the whole market if half of that market is structurally doomed. Indexes packed with legacy companies in shrinking sectors are going to start looking more like value traps than wealth builders. This isn’t the end of investing in equities, but it might be the end of investing without thinking.

Some sectors aren’t just going to suffer—they’re about to walk headfirst into a demographic buzzsaw.

First-order losers are the easy ones. Consumer discretionary companies, built on endless demand from eager, youthful spenders, will find their audience vanishing. Think trendy clothes, impulse gadgets, or anything marketed as “cool.” Bad news: retirees don’t really care what’s cool. They want comfortable, practical, or medically beneficial. Good luck pivoting from selling the latest streetwear to orthopedic shoes.

The education industry is another obvious casualty. Fewer kids means fewer schools, fewer textbooks (is anyone even reading textbooks anymore?), and fewer after-school anything. Japan already has schools shutting down by the hundreds. South Korea’s universities are begging for students. If your portfolio is heavy on education stocks, it might be time to start hedging with funeral homes. Baby diapers are already being outsold by adult ones in Japan. That’s not a stat—it’s a punchline.

And let’s spare a thought for traditional homebuilders. Their entire business model assumes perpetual suburban sprawl. But when young families vanish, so does the sprawl. That shiny new subdivision? It’s tomorrow’s ghost town. Builders will have to pivot to retrofitting aging homes, urban infill, or senior living. None of those scale like cul-de-sacs did in the ‘90s. And the margins? Don’t ask.

Second-order losers are those caught in the blast radius. Retail banks, for instance. No young people means fewer mortgages, fewer car loans, fewer credit cards. Loan books don’t grow when the population doesn’t. Add to that falling household formation, and banks end up fighting over a shrinking pool of creditworthy customers. Spoiler: the customers are winning.

Same goes for parts of the consumer and logistics supply chains that lived off the backs of the above sectors. If people aren’t moving, furnishing new homes, or shipping impulse buys, those warehouses and trucking firms start looking less like infrastructure plays and more like stranded assets.

Third-order losers get trickier. Take marketing agencies. For decades, they thrived by being the middlemen between brands and consumers. But now? The big dogs—Google, Meta—are going direct. AI tools are replacing creative teams and planners at scale. You don’t need an agency when a machine can write ten versions of your ad and target them better than a 20-person team ever could. Add shrinking ad budgets (thanks to stagnant consumer demand), and you’ve got a whole tier of the economy quietly becoming obsolete.

Media? Also under pressure—but not necessarily dying. In fact, it might just morph. An aging population with more free time might still consume plenty of content—but what kind? Fewer superhero reboots, more documentaries about knee replacements. Productivity gains might free up time, yes—but attention is still a finite resource. Those who adapt (and target seniors well) could thrive. Those who keep making TikToks for a disappearing audience of 18-year-olds? Not so much.

And of course, this is all just the demographic lens. It’s not fate. Great companies will adapt their services, innovate, and stay relevant. But it won’t be easy. These are structural headwinds, not passing trends. Pivoting an entire product line—or an industry—takes time, capital, and a lot of pain. Not everyone makes it through the turn.

It’s not all doom and gloom. Companies smart enough to pivot their strategies toward aging demographics can still thrive. Healthcare and eldercare companies will do incredibly well—it’s hard to lose money when your customer base grows daily and is highly motivated (i.e., desperate) to stay healthy. Biotech, pharma, orthopedics (think hip replacements, joint implants), dementia care—these are your new growth stocks. It might not be glamorous, but let’s face it: aging is one industry with guaranteed repeat customers. The markets aren’t stupid—we’ve already seen how healthcare names command rich valuations, even after the post-COVID hangover.

Second-order winners start with everything that enables these sectors to scale. Diagnostics, medical equipment suppliers, health IT systems. If hospitals and eldercare facilities are the picks, these are the shovels. Even adjacent players—think real estate companies building medical office space or assisted living developments—could quietly outperform.

Automation, AI, and robotics also win big. With fewer workers and rising wages, robots become the cheapest employees in town. Companies providing automation solutions—warehouse robots, automated customer service, AI-driven software—will have customers knocking down their doors, desperate to solve the labor shortage problem that won't magically disappear. Bonus points for anyone selling robots that can lift a person out of a bathtub or deliver meds without getting sick.

Productivity tools, enterprise software, and advanced manufacturing tech also stand to gain. When growth slows, productivity matters more. Companies will throw money at anything that helps squeeze more out of fewer workers. Think less “foosball-table-in-the-office” tech, and more “software-that-replaces-three-employees” tech. Again, look at the enablers—cloud infrastructure, cybersecurity, and companies that train the workforce to use these tools (or just replace the workforce altogether).

And don’t underestimate senior-targeted finance and housing. Life insurers shifting from selling policies to offering retirement income products (annuities, reverse mortgages) suddenly have a captive audience. Hello to the Apollos, Brookfields, and KKRs of the world—retirement is their next frontier. Second-order boost? Asset managers pivoting toward drawdown products and long-duration fixed income—this is where the capital flows will go.

Likewise, travel companies targeting older retirees with disposable income (and endless free time) could see booming demand. Cruise ships and senior resorts are about to get very busy—assuming anyone is left to staff them. Third-order winners? Logistics firms servicing those resorts, specialty healthcare providers offering on-board medical care, and insurance companies selling travel health coverage to the 75+ crowd who still believe Machu Picchu is a good idea.

The point is: there’s still plenty of money to be made. You just have to follow the grey hair—and the incentives.

The demographic mess is playing out unevenly across the globe. Developed markets—Europe, the US, Japan—are in the deepest trouble. Their populations are oldest, their fertility rates lowest, and their growth prospects most constrained. If your portfolio is mostly exposed to developed-market indices, you’re effectively betting on sectors and economies facing demographic headwinds strong enough to blow down houses.

Emerging markets are a mixed bag. India, Indonesia, parts of Latin America, and Africa still have young, expanding populations—for now. The consumer growth story is still credible here, at least temporarily. But don’t get too comfortable: fertility rates are plummeting even faster in emerging markets than they once did in developed countries. China’s workforce is already shrinking; Brazil’s fertility rate is already below replacement; India’s dropping too.

The takeaway? The emerging market consumer story isn’t dead yet, but you’ll need to pick your spots carefully. Simply buying into the narrative of "young countries equal growth" is a lazy bet with a looming expiration date.

The easy days of investing are done. Passive indexing built on endless population growth and automatic economic expansion has officially expired. If you’re still cruising on autopilot, relying on those old assumptions, your returns are about to get painfully real. Welcome back to reality, where alpha matters again—good news for stock pickers, tough luck for everyone else.

Here’s your new investing mantra: re-check every DCF, question every growth assumption, and kill the notion that demographics will magically save your portfolio. If your valuations depend on continuous revenue expansion because of a growing customer base, well, welcome to the real-life version of musical chairs—and guess what, the music just stopped.

But let’s be clear: this isn’t just about gloom. Active investing is about to enjoy a genuine renaissance. Stock picking, disciplined valuation, and nuanced understanding of sectors and markets will regain the prominence they deserve. Rather than passively floating upwards with the tide, investors now have a chance to actually demonstrate skill and insight—assuming they have any.

There’s hope here, too. Human beings are extraordinarily good at adapting. Businesses that recognize demographic shifts early and pivot accordingly will flourish. Companies leveraging innovation, AI, automation, and productivity improvements—rather than endless market expansion—will thrive. Even shrinking markets present powerful opportunities if you're disciplined enough to spot the pockets of growth. Japan’s small caps, for instance, are quietly entering a new growth era by doing exactly that: solving real problems in a stagnant world. You just have to be paying attention.

The companies that lean into these challenges—those that understand aging populations, invest smartly in automation, or deliver healthcare and services seniors genuinely need—can deliver returns that eclipse the lazy boom-era beta we've all gotten used to.

In short, don’t bet on demographics. Bet on adaptation. Bet on innovation. Bet on the human capacity to solve big, uncomfortable problems. The boom is over, sure. But for investors who embrace reality and think clearly, there’s real money to be made in the aftershock.

If you enjoyed this piece, please give it a like and share!

Thanks for reading Edelweiss Capital Research! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support our work.

If you want to stay in touch with more frequent economic/investing-related content, give us a follow on Twitter @Edelweiss_Cap. We are happy to receive suggestions on how we can improve our work.

Sources:

McKinsey Global Institute – Dependency and Depopulation? Confronting the consequences of a new demographic reality, January 2025 mckinsey.commckinsey.commckinsey.com.

McKinsey Global Institute – demographic data and projections (UN data cited) mckinsey.commckinsey.commckinsey.com.

Western Asset Management – Aging Populations and Public Debt, June 2024 westernasset.comwesternasset.com.

Investopedia – How Demographic Trends Could Affect Your Portfolio investopedia.cominvestopedia.com.

Business Insider – Japan’s property market and abandoned homes businessinsider.combusinessinsider.com.

Shipping & Commodity Academy – Commodity Trading in a World of Shrinking Population shippingandcommodityacademy.comshippingandcommodityacademy.com.

Reuters – Japan’s diaper makers look to adult market as births fall, 2023 reuters.com.

Reuters – School closures spread in ageing Japan as births tumble, 2023 buddhikaweerasinghe.com.

Goldman Sachs – projection of emerging vs developed market cap share goldmansachs.com.

.png)