Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. This edition is for everyone, but please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to fully unlock this essay and 200+ others from the archive. Your subscriptions make my writing sustainable for the future. Alternatively, you could check out my book: FLUKE: Chance, Chaos, and Why Everything We Do Matters.

When I was a kid, I could rattle off telephone numbers. Landlines. Clunky, oversized cell phones, bricks in purses. I knew the digits by heart. I still do.

My best friend down the street. My parents. The girl I had a crush on (well, okay, her parents’ house). I used to know street names, too. Grids and lines, meandering through my head, a 12 year-old human MapQuest. You could learn a place in those days with 1990s GPS technology: Go Play Somewhere.

Then, I got a cell phone. For digits and coordinates, that part of my brain was siphoned off into the little flip phone. It never recovered. I don’t know any new phone numbers. Street names are passé. What3Words is the future. It’s now easy to ignore the surrounding environment. After all, you can always just look it up. You got lost? How? Did you forget to charge it?

But this isn’t about phone numbers or navigation. It’s about how technology clearly changes our minds. And there is a risk that today’s siphoning of young brains into phones and laptops isn’t just happening with maps and digits, but with critical thinking and complex language.

Every piece of technology can either make us more human or less human. It can liberate us from the mundane to unleash creativity and connection, or it can shackle us to mindless robotic drudgery of isolated meaninglessness.

Contrary to popular opinion, the latter option is not inevitable. We get to choose whether—and how—we adopt technology that can eviscerate our humanity.

When artificial intelligence is used to diagnose cancer or automate soul-crushing tasks that require vapid toiling, it makes us more human and should be celebrated. But when it sucks out the core process of advanced cognition, cutting-edge tools can become an existential peril. In the formative stages of education, we are now at risk of stripping away the core competency that makes our species thrive: learning not what to think, but how to think.

What makes us unique among other species? It is not merely our social complexity—ants, meerkats, and naked mole rats exhibit eusociality like us. Instead, we are set apart by traits that exist nowhere else in nature: profoundly self-aware consciousness, sophisticated culture made possible by unparalleled linguistic complexity, and, above all, our peerless cognition.

Our minds make us human—and language provides the social architecture of our thoughts.

Artificial intelligence is already killing off important parts of the human experience. But one of its most consequential murders—so far—is the demise of a longstanding rite of passage for students worldwide: an attempt to synthesize complex information and condense it into compelling analytical prose. It’s a training ground for the most quintessentially human aptitudes, combining how to think with how to use language to communicate.

If you want to know what you think about a topic, write about it. Writing has a way of ruthlessly exposing unclear thoughts and imprecision. This is part of what is lost by ChatGPT, the mistaken belief that the spat out string of words in a reasonable order is the only goal, when it’s often the cognitive act of producing the string of words that matters most.

Alas, with this melancholic eulogy, it is time to sign the death certificate. Here lies the student essay—RIP, old friend—slain by OpenAI.

I personally conducted a rigorous post-mortem over the past several weeks while grading 95 student essays. Many were wonderful: a pleasure to read, original and interesting, pockmarked with a few typos, but with clear evidence of a curious, thoughtful mind.

But, for others, something has changed.

Miraculously, in the last year, mistakes of spelling and grammar have mostly disappeared—poof!—revealing sparkling error-free prose, even from students who speak English as a second or third language. The writing is getting better. The ideas are getting worse. There’s a new genre of essay that other academics reading this will instantly recognize, a clumsy collaboration between students and Silicon Valley. I call it glittering sludge.

At the same time, in a totally unrelated development, some students have adopted a bold academic strategy: citing books and articles that do not exist.

(In one particularly amusing example, a student cited me in an essay, drawing from my book, Fluke. The only problem: the alleged author of the cited text in the bibliography was not listed as Brian Klaas, but one “Benjamin Fluke.” Right title, wrong author, wrong publisher, wrong year. Well played, ChatGPT).

The death of the student essay is not merely an academic concern. It is not just a problem for young people hoping to get good grades, nor is it only relegated to the realm of my fellow elbow-patched nerds. Instead, the rapidly improving ability to impressively mimic human language poses an existential threat to traditional methods of crafting smarter minds—which thereby challenges the future of human cognition.

In Dune, Frank Herbert features an exchange in which individuals are tested for their humanity.

“Why do you test for humans?” he asked.

“To set you free.”

“Free?”

“Once, men turned their thinking over to machines in the hope that this would set them free. But that only permitted other men with machines to enslave them.”

Despite the obvious risks of ChatGPT and its more obscure cousins, we need not retreat into the well-trodden trenches of luddites vs. tech bros. There’s a smarter way of understanding the rise of LLMs while preserving our critical thinking, all while shining a crucial, easily overshadowed light on how our ability to reason with language is the essence of humanity.

And it starts with student essays.

On the first day of my Global Politics class, I level with the students: I’m going to help you better understand the world, but that’s not what this class is really about. In twenty years, the world will be different. In 2045, you won’t get a pop quiz on the provisions of NATO’s Article 5. My goal is to help equip you to understand an ever-changing world. And that’s not about what you know, but how one comes to know things. Developing that mental tool through education will allow you to build a more fulfilling life.

There is a difference between intelligence and knowledge. As I explained in a previous essay on octopuses and intelligence, the core concept of intelligence is that it makes additional information useful. Without intelligence, knowledge can never be fully used, a tragic curse—like being illiterate in the Library of Alexandria.

Now, in the age of the internet—when the Library of Alexandria could fit on a medium-sized USB stick and the collected wisdom of humanity is available with a click—we’re engaged in a rather large, depressingly inept social experiment of downloading endless knowledge while offloading intelligence to machines. (Look around to see how it’s going).

That’s why convincing students that intelligence is a skill they must cultivate through hard work—no shortcuts—has become one of the core functions of education.

As Troy Jollimore puts it:

There are always students who are willing but who feel an automatic resistance to any effort to help them learn. They need, to some degree, to be dragged along. But in the process of completing the assigned coursework, some of them start to feel it. They begin to grasp that thinking well, and in an informed manner, really is different from thinking poorly and from a position of ignorance.

That moment, when you start to understand the power of clear thinking, is crucial. The trouble with generative AI is that it short-circuits that process entirely. One begins to suspect that a great many students wanted this all along: to make it through college unaltered, unscathed. To be precisely the same person at graduation, and after, as they were on the first day they arrived on campus. As if the whole experience had never really happened at all.

Previously, there was a tight coupling between essay quality and underlying knowledge assembled with careful intelligence. The end goal (the final draft) was a good proxy for the actual point of the exercise (evaluating critical thinking). That’s no longer true.

For technical reasons that I won’t get into, detecting the cheats is a losing battle. There’s no surefire way to catch someone using AI tools and the technology is evolving so rapidly that agentic models, which basically can operate autonomously and follow the exact process a student would use in researching and writing an essay—just much faster—will soon make AI-written essays impossible to catch.

Aware of my inability to detect AI use with certainty, I implored the students: please don’t use AI. It’s terrible for you. It’s terrible for me, a dystopian experience of spending weeks giving detailed constructive feedback to a machine. I strongly suspect—but can’t prove—that many didn’t listen.

Nonetheless, I have caught students using ChatGPT, but mostly because of adjustments the students made—or didn’t make—to citations. There were the so-called hallucinations, in which ChatGPT invented a fake source; other times, the source was real but the quote was not; and then there were the essays that cited literally zero course readings even though engagement with them was required, a bright crimson red flag.

More than once, a student quite clearly used ChatGPT, but to try to cover their tracks, they peppered citations for course readings—completely at random—throughout the text. For example, after a claim about an event in 2024 in Bangladesh, there was a citation for a book written ten years earlier—about the Arab Spring. “Rather impressive time machine they must have had,” I commented.

After a career working to develop expertise, countless hours teaching, and my best attempts to instill a love of learning in young minds, I had been reduced to the citation police.

Worse, it meant that my ability to assess students—a precursor to helping them improve—is completely kneecapped, as though a doctor is asked to diagnose a patient while not knowing whether the blood for the test came from their body or someone else’s. And the value of those assessments for others—as proxies for future hiring decisions, for example—becomes worthless if it’s unclear who wrote the work.

Next year, my courses will be assessed with in-person exams.

Language is humanity’s superpower. Without it, culture, cultural evolution, global cooperation, and the accumulation of knowledge across generations would be impossible. Through linguistic offshoots, such as writing, we are able to practice a unique phenomenon: exbodiment, in which byproducts of our cognition can be captured, stored, shared, and passed through generations.

Chimpanzees and crows and octopuses may be clever, but the impossibility of an eight-tentacle Shakespeare provides a ceiling to intelligence and incremental technological progress in other species. Our brains, capable of sophisticated communication through the most complex language on Earth, are an evolutionary miracle—one that has seemingly happened just once. Why would we seek to jettison our superpower? Turning language over to machines is the equivalent of a bird clipping its own wings.

Even for those in the harder sciences, the necessity of becoming competent in social thinking and philosophical reasoning has never been more urgent. We live in an era of unprecedented tools—the first generation with the ability to fundamentally change what it means to be us—and those with the technological know-how also need to know why.

We can. The more difficult question is whether we should. The correct answer to that harder question can never be provided by an algorithm or a machine learning model.

For now, much of the focus on ChatGPT’s capacity to disrupt is economic: will it lay waste to entire industries while putting poets and painters on the streets? Those concerns are real and important.

But the secondary consequence of that impending economic disruption is more abstract: does the value of a text depend on its creator being human? (I, for one, plan to never read an AI-generated novel, though I suspect that ChatGPT is already seeping into writing that we unknowingly consume as a human-tech hybrid. I have never used AI-generated text in my writing).

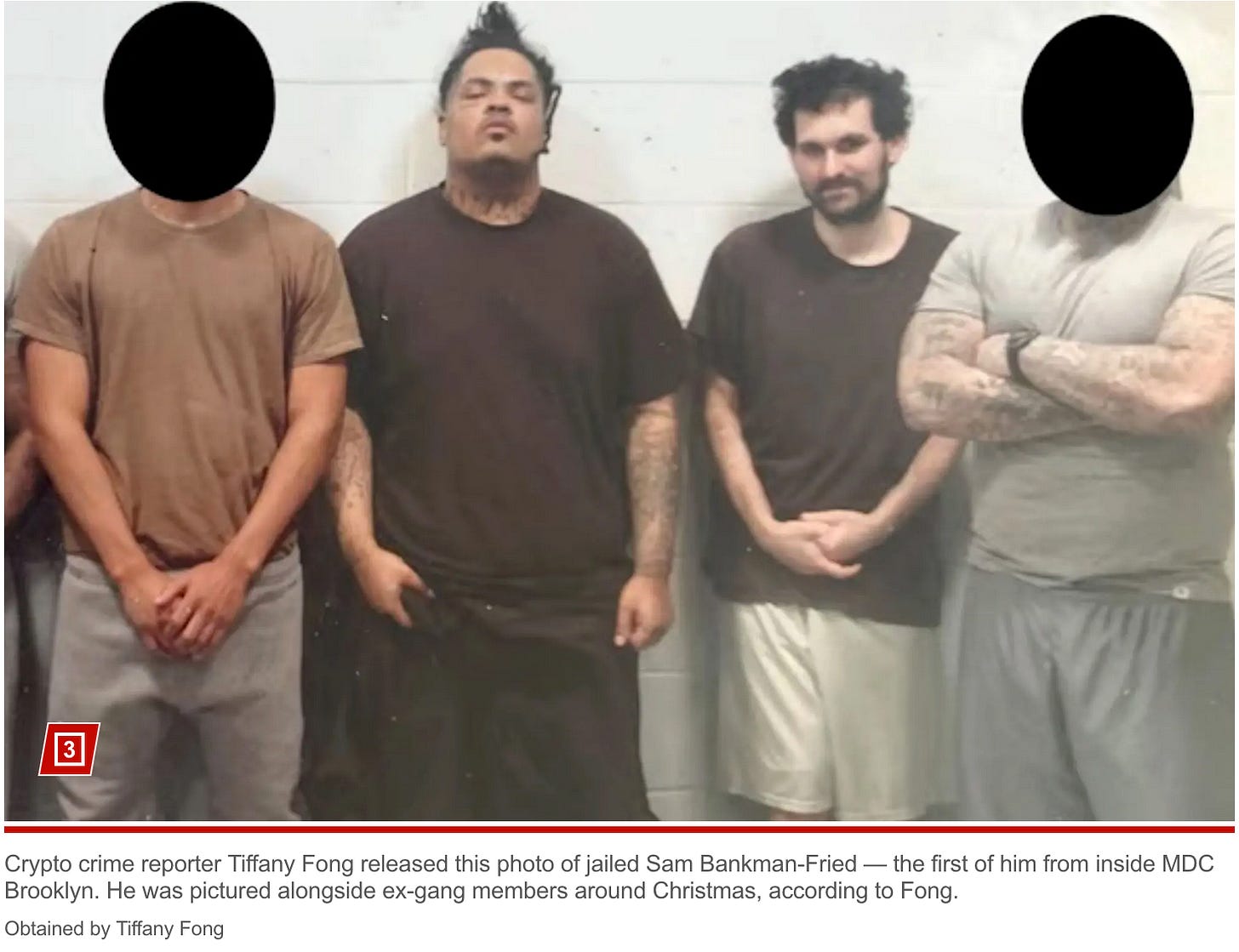

Alas, there is a group of people—let’s call them, hm, how about “fools”—who believe there is no important distinction between an AI-generated summary of a book and the book itself. Disgraced cryptocurrency swindler Sam Bankman-Fried, for example, once told an interviewer the following, thereby helpfully outing himself as an idiot.

“I would never read a book…I’m very skeptical of books. I don’t want to say no book is ever worth reading, but I actually do believe something pretty close to that. I think, if you wrote a book, you fucked up, and it should have been a six-paragraph blog post.”

Extend his prison sentence.

But in all seriousness, this attitude is indicative of the less discussed, but arguably far more important, disruption of new technology such as ChatGPT. By mistaking language as merely a tool that’s a means to an end—little different from a spatula—too many people have lost sight of the fact that understanding language provides the basis of smart thinking. If you offload it to machines, future generations will never develop their own superpowers, leading to a net loss of critical thinking ability among our species.

This isn’t to say that AI is uniformly bad—it’s clearly not—but that we must not fall into the trap of mistaking the outputs of writing (which are increasingly substitutable through technology) from the value of the cognitive process of writing (which hones mental development and cannot be substituted by a machine).

It would be a catastrophically unwise decision for humanity to abandon a key step in training young brains simply because they can now clack a few keys and produce something that sounds intelligent even as they never become intelligent.

Above all, however, my eulogy for the student essay is a lamentation for what could be lost. Many of the greatest joys of my life have been unleashed inside my own head, from childhood nights devouring an entire book to the unrivalled feeling of intellectual discovery through the slow, contemplative process of exploring the ideas of countless people I’ll never meet.

Lisa Lieberman captured this ethos in a 2024 essay about her experiences as a college student—and what she fears for her students in the nascent AI age:

As I lay there reading the writer’s words, they came to life — as if the author were whispering in my ear. And when I scribbled my notes, and wrote my essays, I was talking back to the author. It was a special and deep relationship — between reader and writer. It felt like magic.

This is the kind of magic so many college students will never feel. They’ll never feel the sun on their faces as they lie in the grass, reading words from writers hundreds of years ago. They won’t know the excitement and joy of truly interacting with texts one-on-one and coming up with new ideas all by themselves, without the aid of a computer. They will have no idea what they’re missing.

I love feeling like I’m part of the collective human experiment, in which my brain is, quite literally, architecturally reshaped, down to the neuron, by ideas unleashed by thousands of other minds across time and space. That thrilling feeling was made possible by the hard toil of education, which gave me better opportunities for an intellectually enriching life well-lived.

The death of the student essay is not a tragedy because of a lost assessment tool. Instead, it is a warning: that if we get dazzled by new-fangled tools to the extent that we fail to understand the importance of language and cognitive development, we risk destroying the essence of what makes us special. Without due care, our most beautiful aptitude could be stripped bare to a soulless output, unable to be fully appreciated by untrained minds.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. If you value my work, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to support it. Your support makes this possible—and costs only $4/month. And please share this article far and wide—on social media or with friends, family, mortal enemies, etc.

.png)