Welcome to Combat Threads! After far too long, we are back. This, of course, has everything to do with Avery Trufelman’s new season of Articles of Interest, all about military uniforms and outdoor gear. I had the absolute privilege of consulting on the season and made a few appearances. This week’s Chapter covered a story that is very near and dear to me: the creation of the field jacket. This invention was revolutionary and not without controversy – a story that Avery does a superb job in weaving together. But here at Combat Threads, we wanted to focus on just one aspect of this story: What makes the field jacket and its design uniquely American. To help tell this story, I teamed up with Joshiua M. Kerner (who is heavily featured in this season AOI) and Tom Kelly, two longtime friends, research companions, and historians whose voices you cannot tell the story of the field jacket without.

* * *

The official history of the field jacket, produced by the US Army, was titled Designed For Combat. There could be no truer statement. This garment and the idea that soldiers should wear uniforms explicitly and solely designed for fighting may both seem mundane and common sense to us. But, during World War II, it was a revolutionary approach to the design of military clothing.

Uniforms, at their core, are a practical invention. They must protect and serve the wearer as well as identify them – tell the postman from the milkman, your friend from your enemy. In the case of military uniforms, they have also held a very symbolic meaning. The symbolism of the uniform has arguably been the predominant purpose of uniforms through the ages, including most of the 20th century, when the uniforms soldiers wore into combat were the same ones they wore on the parade ground. Thus, uniforms, while projecting power and acting as a signifier of place, failed in most cases to be utilitarian for the soldiers.

The development of the first military field jacket began in late 1939 when the War Department Uniform Board was directed to develop “some type of windbreaker or lumberjacket for field service.” The job of designing such a jacket was taken up by Major General J. K. Parsons. Gen. Parsons envisioned that, instead of soldiers going to war in their service coats—woolen jackets with brass buttons, better suited for dress but customarily worn in the field as well—they should wear a jacket specifically for field wear. He settled on a lightweight cotton jacket with a wool-shirting lining, about waist-length, largely based on golf jackets of the period. The result was what would become the M-1941 field jacket.

At the end of 1942, the Quartermaster Corps decided not only to improve the field jacket but also to simplify its own supply by developing a more universal garment to replace the plethora of specialty garments such as those for parachutists and tank crewmen. Stepping into the breach was the head of the Quartermaster Corps’ research and development: Georges Doirot. A French immigrant, World War I veteran, and economics professor from Harvard.

As head of research and development, Doriot brought an outsider’s perspective desperately needed in the Quartermaster Corps. He not only heavily solicited the outdoor clothing industry for advice, but he also proceeded to do the first scientific testing of the garments to try and remove bias and other problems endemic to earlier uniform designs. As a 1944 Quartermaster Corps publication put it, “immediately upon enactment of the first conscription law, almost the entire roster of American scientists, explorers, and manufacturers were called upon to cooperate with the Office of the Quartermaster General in development of clothing and equipment.” Now these scientists, explorers, and manufacturers worked to develop the M-1943 field jacket.

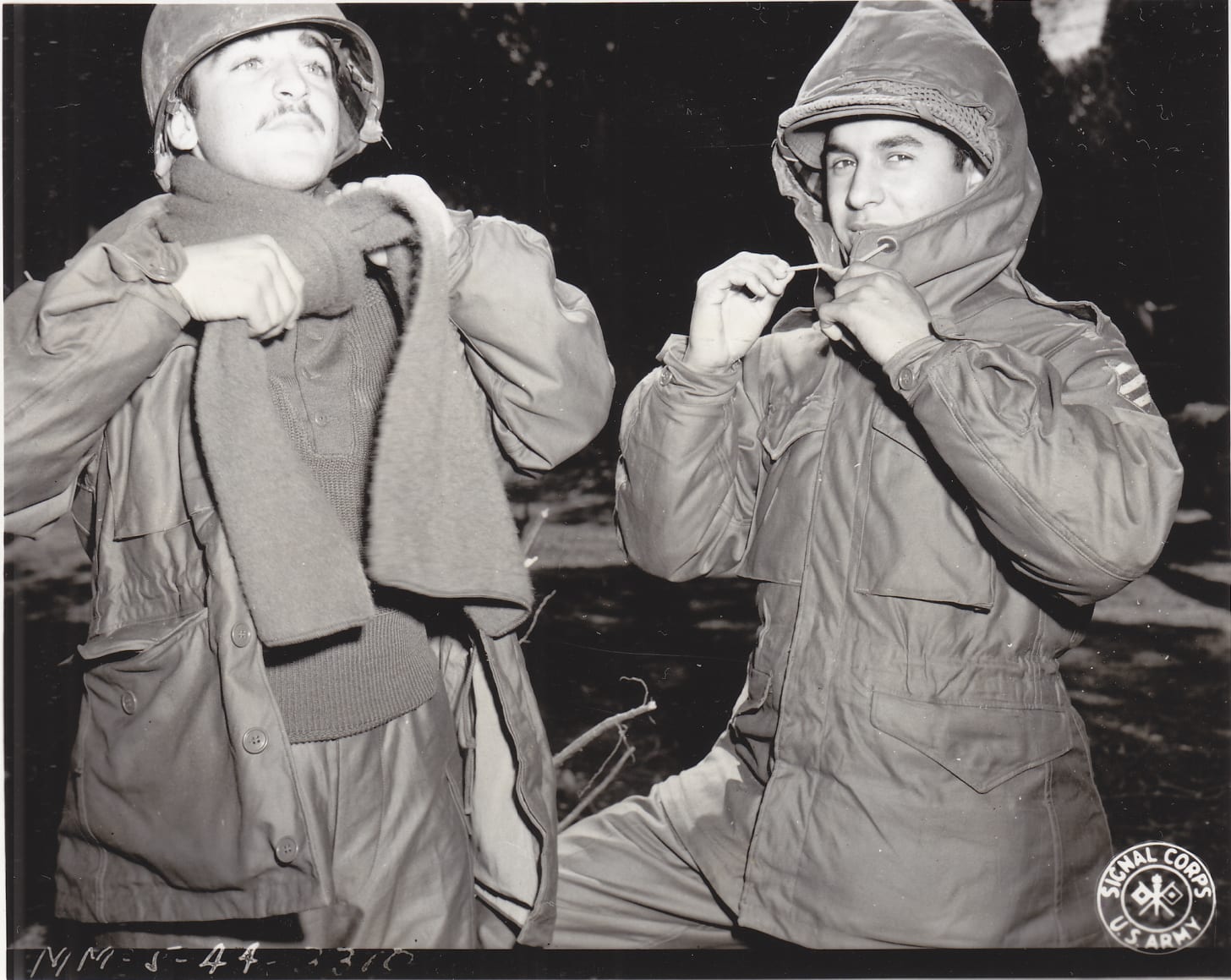

This research and testing resulted in the M-1943 Field Jacket. The new jacket, designed by Israel Freedman, Max Udell, and Lou Weitz—all of the Office of the Quartermaster General and former garment manufacturers—was made from a 9 oz. olive drab sateen shell with a 5 oz poplin lining. The jacket was meant to fit loosely, allowing multiple layers to be worn below, and featured a drawstring waist that could be cinched or loosened depending on the layers and weather. It reached down to the hip and featured four large pockets. The two chest pockets were bellowed and designed to hold soldiers’ equipment like rations and hand grenades. The lower pockets, below the waist, were internal, much larger, and had internal suspension, meant for soldiers to store ammunition and other personal items. The jacket featured a button-front closure and pocket flaps, all covered to prevent snagging.

Much has been made of the utilitarian nature of the M-1943 field jacket. Of course, in designing a garment purely for field use, utility was a major consideration, but there was form as well as function. The new jacket reflected both the American soldier as a citizen and a consumer. As one handbook put it, “The American man, accustomed to decently fitting clothes in civilian life, should definitely be happier wearing a jacket styled in light of his sense of what looks right as well as its ability to take punishment.”

The design of the jacket reflected an American attitude towards combat and clothing. In the words of one infantryman, “killing is a dirty business, and to me, it seemed immoral for professional killers to look too clean.” Like that other bastion of American style—jeans—the field jacket was designed as workwear.

The collection of people brought together to design the jacket, from physiologists to pattern cutters, reflected the immense human potential that was promised by the diverse and inclusive vision of the United States. A society that could, when prompted, bring together WASP explorers, immigrant businessmen, and Jewish garment workers to create a jacket that could help beat back fascism.

The military that wore the field jacket was just as diverse as the team that designed it and the workers who produced it into the millions. Production of the field jacket was contracted to firms across the United States, but as with many of the Army’s uniforms, manufacturing was largely centered in the Northeast. Companies like Sigmund Eisner Co. Inc. (Red Bank, New Jersey), The Navytone Co. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), The Monarch Coat Co. Inc. (Boston, Massachusetts), and many others produced almost 17.5 million field jackets between 1943-1945.

The development and ultimate success of the M-1943 field jacket embodied the core strengths of the American way of war, a method that mastered practicality and logistics on a scale that none of the other combatant nations ever rivaled. At the same time, Britain’s soldiers were clad almost entirely in the same manner as when the war began, and German forces were equipped in a logistically haphazard manner and with uniforms repurposed from defeated foes.

In stressing function over form and results over tradition, the United States accomplished the most meaningful developments of military garments in recent history by simply asking, “What does the soldier want?” Made all the more impressive by being perhaps the only time in military history that a standard issue garment was made more complicated, not less, by the end of the war, compared to the beginning.

Designed with the well-being of the soldier at the forefront, in a truly astonishing array of sizes, the jacket was meant for Americans of all shapes and sizes. An egalitarian military based on democratic principles, the defeated Nazi’s were struck by how American soldiers looked. “The impression GIs have made on Germans is naturally mixed,” a postwar book laid out, with some staunch Nazi’s pointing out the “sloppiness” of Americans with their hands in their pockets and baggy field jackets unbuttoned. Others were impressed “that the officers’ field uniform is identical to that of the men.” One German driver put it succinctly, “The American soldier is sloppy. The German soldier is very stiff. But the American soldier, he seems to always win.”

Those jackets, made by a wartime workforce of men and women of all creeds and ethnicities, became the literal mantle of American victory in the Second World War. While still segregated, American fighting men came from all corners of the country and globe, of every possible ethnic, racial, and religious makeup. It was the M-1943 field jacket that adorned the majority of American soldiers who crushed Nazi forces in Northwest Europe and Italy, and the soldiers and Marines who occupied Japan. After the war, the field jacket would continue to be improved upon and become a staple of military uniform design in the US and around the world well into the 21st Century.

Till next time,

C.W.M., J.M.K, & T.H.K.

* * *

.png)