You’re reading Fix The News, a weekly roundup of hidden stories of progress. We give away 30% of our subscription fees to charity. Give someone a gift subscription. Get a group subscription for friends, family or your organisation. Listen to our podcast. If you need to unsubscribe, there’s a link at the end.

Black Range Rovers outnumbered yellow cabs on the streets of Manhattan during the last week of September. The UN General Assembly had descended on New York, squeezing the world’s dictators, diplomats and beleaguered aid agencies into a few blocks of Midtown. It was unseasonably hot, and inside hotel ballrooms the recycled air was thick with the density of too many important names in too little space.

On the surface, business as usual. Beneath it everything was breaking, and everyone knew it. There was a slump in people’s shoulders, and empty seats because of the no-fly lists. Fewer high heels, more sneakers. The cynical scheming and brute force of international affairs felt physically present, wedged in throats and suspended in the silences between panels.

“This does feel like a crisis meeting,” Tjada D’Oyen McKenna, CEO of Mercy Corps, told us on Monday morning. Her organisation works on the frontlines of disaster relief, serving around 37 million people in over 40 countries; we connected with them earlier this year when we helped fund a sanitation program in Nigeria in danger of shutting down due to USAID cuts. “When everything feels like it’s on fire it’s still good to come together – to remind you that there’s still so much we need to do.”

The Greek root of crisis, κρίσις, means to sift. And that’s what was happening across those five days in New York. Everything was changing — the old models, the old certainties, the old ways of moving money and measuring impact. It felt like witnessing a page turning in real time, suspended between the end of one global chapter and the beginning of the next.

The two of us had been invited to attend as media for the 20th Clinton Global Initiative, an annual gathering that brings together leaders from philanthropy, business, government and nonprofits. Attendees have to make a Commitment to Action, which can be anything from a small local project to a massive global venture. There’s a perception that events like this are status games for globalists — big names competing to outdo each other. But as we learned last year, CGI is more like a watering hole. Real partnerships form here, and the model has launched some genuinely world-changing initiatives.

This year, they ditched the 20th anniversary celebrations. Instead, the organisers convened working groups — three-hour sessions behind closed doors, no media allowed, putting people who could actually move money and get things built into rooms together. Democracy. Human rights. Crisis response. Climate. Healthcare. Truth and information. Education. With many attendees hunkered down, the reception areas felt less crowded and buzzy than last year, but that was the point.

It was in the public events however, where the full scale of the crisis became clear. During the first few hours, panelists tiptoed around the elephant in the room until, finally, in the first session after lunch, someone said it: the United States is the world’s largest single development aid donor. Under the Trump administration, more than 90% of that funding has been cut.

Not reduced. Cut. The room already knew this, of course. Most of the philanthropists and NGO leaders in attendance had built their entire operating models alongside US-funded foreign aid. They’d structured programs around the assumption that the money would keep flowing. Now a lot of it was gone, and everyone was scrambling to figure out how to survive.

“Not everything’s going to get funded,” said philanthropist Abigail Disney, cutting through the careful diplomacy of the morning. It was the kind of statement that would have felt harsh in previous years, but here it came as a relief, someone finally saying what everyone had been thinking.

WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus admitted that, as he spoke, staff were being given notice due to budget cutbacks — the same people who had worked day and night to get the world through the Covid pandemic. The aid space was being winnowed in real time. Organisations without boots on the ground were packing up. There was talk of hiring more local staff, of buying supplies from local markets instead of importing them. Eventually someone made the obvious point. “Shouldn’t we have done this ten years ago?”

Critiques of foreign aid are legion: it creates dependency, undermines local institutions, props up corrupt governments, crowds out private investment. The debate is not new. William Easterly laid it out in The White Man’s Burden in 2006, and Dambisa Moyo followed in 2009 with Dead Aid, posing a provocative thought experiment: “What if, one by one, African countries each received a phone call, telling them that in exactly five years the aid taps would be shut off—permanently?”

Well, they’d just gotten the call. Except it wasn’t five years. It was five months. USAID has famously been fed to the woodchipper, and Canada, Britain, and Germany are cutting their budgets too. Rajiv Shah, who led USAID for five years, admits that as shocking as the cuts are, the old model was broken. It was designed and controlled by wealthy donor countries, not by the people receiving it. The result was a bureaucratic nightmare: countries like Malawi have to write 50 different strategic plans for funding from 166 different sources for half of their healthcare.

The system did need to change - but it had happened far quicker and more cruelly than anyone expected. Which is why the dominant topic in every room, every panel, every hallway conversation, was money. Not how to get more of it, but what replaces it when it’s gone.

One concept that kept showing up: innovative financing. The idea is deceptively simple. There are vulnerable people who want to help themselves but can’t access capital, and banks who are willing to lend — if they can get assurance that these borrowers aren’t a risk. So, instead of just giving money away, why not use it to de-risk loans in places where banks won’t usually go?

One of our favourite examples of this came from Tonya Allen of the McKnight Foundation, who’s leading Groundbreak, a $5 billion initiative getting loans to underserved communities in the United States. “The guarantee pool is already established so borrowers don’t have to find people to guarantee them,” she explained. The hope is that as businesses succeed, “we get more data that these people are not more risky just because they live in certain zip codes.”

Another striking example came from Colombia. Mercedes Bidart, who runs an organisation called Quipu, explained that around a third of the country’s GDP is made up of unbanked micro-businesses. Many would love a loan to upgrade from the street corner to a shop, but no bank is going to send a risk assessor to talk to a woman selling tamales on a stand.

That’s where Quipu comes in. Bidart and her partners spent years collecting digital and physical footprints of thousands of micro-businesses, and then fed the data to AI. Now micro-business owners can use their phones to show Quipu a video of their business, testimonials, text messages, even social media accounts, and get accepted for a loan.

Another example? Off-grid solar. Since 2020, mini-grids have connected more people to electricity across Africa than national grids. However, the returns on those individual systems are too small to interest institutional investors, despite being life-changing for the people who get them. As Rachel Moré-Oshodi, CEO of ARMHarith, pointed out, when someone says “infrastructure in Africa,” most institutions politely decline. That’s why they’ve started bundling the systems, allowing institutions to put money into 100 or 1,000 mini-grids, allowing for steady, long-term returns while spreading the risk.

The most interesting new funding idea, however, came from the Coalition for Mental Health Investment, launched at CGI last year to bridge the funding gap for mental health — which receives less than 2% of global health funding. When we reconnected with their team this year, they’d found creative workarounds by borrowing a model from conservation.

Over the last five years, debt-for-nature swaps have released billions of dollars for environmental protection. The concept is simple: a country’s debt gets reduced or bought back at a discount, and in exchange, they commit to spending the savings on conservation. Ecuador’s 2023 deal bought back $1.6 billion in debt for $644 million, saving the country around a billion dollars in repayments. In return, they’re spending $18 million a year for 20 years protecting the Galapagos. Belize cut its debt by $250 million and established a conservation trust of US$180 million for marine conservation. The model works.

So the mental health coalition asked: what if we could do the same for brain health? They’re now exploring using debt-for-health swaps and outcome-based financing not just to treat mental illness, but to invest in the upside — cognitive functioning, creativity, resilience. As Erica Coe, Partner and Global Executive Director of the McKinsey Health Institute told us, “A growing number of countries are realising the importance of investing in the brains of their future workforces. When you think about the economic nature of it, this is what will make our society run.”

Shrinking aid budgets weren’t the only things driving change. There was also a sense of impatience this year. Take health. On one panel, Brendan Carr of Mount Sinai surprised everyone when he said “Stop funding hospitals,” He explained that hospitals are big, shiny projects that donors love, but that disproportionately treat diseases that are complex or rare — not the ones killing people everywhere. Vaccines save the most lives, followed by maternal health, followed by training people who can prescribe drugs or do basic medical work. Not overpaid doctors, but hygienists, wound care specialists and nurses.

Or energy access. During a panel on entrepreneurship, Sandra Chukwudozie, the CEO of Salpha Energy, pointed out that that over 600 million people across Africa still don’t have electricity. The impact is profound; families have to navigate late evenings in darkness or by candlelight, local clinics cannot be as effective after sunset and businesses close early because they lack power.

“I’m sitting here in New York and across the river is New Jersey where the first incandescent light bulb was made at commercial scale 146 years ago. Why is this still a problem?” Ten years ago, Sandra left her job at the United Nations, moved back to Nigeria, and founded Salpha Energy. Today, they’ve connected over two million people to solar power while reclaiming the supply chain by building out local assembly to design, manufacture and distribute the kits.

There was a lot of this - moments when you realised that the people closest to the problems had already figured out the solutions, and were just waiting for everyone else to catch up.

Integrate Health was another example. Their team was in Manhattan as part of the UN General Assembly, and we caught up with them around a small table in the back of a heaving cafe near the Rockefeller Centre. Started in 2004 as a collaboration between Peace Corps volunteers and HIV activists, the organisation puts women in Togo and Guinea at the centre of the healthcare system; training them to become community healthcare workers to diagnose and treat malaria, diarrhoea, pneumonia and malnutrition in kids, while also supporting other women through pregnancy and family planning.

“It turns out we can shift a lot of the leading causes of death of children and kids under five,” explained Emily Bensen, who leads their global engagement strategy. “You don’t have to go to medical school for eight years to diagnose and treat these illnesses.” Their model is working too. In Togo, child mortality fell by 30% in just five years, at the cost of just $10 per capita. This approach has been essential, as Western African countries traditionally receive up to 15 times less international development money than Eastern and Southern Africa.

Integrate Health didn’t stop there though. In 2021, they helped convince Togo’s government to make maternal healthcare free, meaning that today, more than 600,000 women receive free high-quality prenatal care and delivery. And now they’re taking what they’ve learned to Guinea with a five-year, $15 million commitment in partnership with Gavi to provide primary care to about 200,000 people in rural areas, and support the rollout of the malaria vaccine.

As the days rolled on, the haze set in. Less sleep, more coffee, ideas piling on ideas until our heads felt thick with it all. That particular tiredness that comes from spending all your daylight hours in windowless rooms, choosing the interview over the food break, notebooks full, too many voices insisting on the urgency of their issue until they all started to sound the same. But somewhere in that blur, something shifted. With every conversation banked, that lump in the throat started to ease.

The people on the frontlines aren’t panicking. They’ve been dealing with “unprecedented crisis” for years. They’ve already figured out that change doesn’t come from outsiders parachuting in with five-year plans and brand new equipment. It comes from training people properly, trusting them to do the work, and staying long enough to see it through. And they weren’t scaling back. In fact, a lot of projects were going bigger and bolder.

The biggest news of the week was the announcement that lenacapavir, the HIV ‘miracle drug,’ will now be affordable and accessible in 120 low- and middle-income countries thanks to the coordinated efforts of the Clinton Health Access Initiative and the Gates Foundation. The twice-yearly injection shows almost 100% efficacy in preventing HIV. In less than a year since its announcement, it has already secured generic licensing, attracted major funders, and is slated to begin rollout in 2026.

It wasn’t all bad news on the funding front either. The Gates Foundation announced a historic $912 million contribution to the next replenishment of the Global Fund. Over the next 20 years, the organisation will commit $200 billion to addressing the world’s greatest inequities, double what they’ve spent in the past 25 years.

“We want to make sure we use the next two decades to really build towards a world that has no child dying of a preventable disease across the world,” Gates Foundation CEO Mark Suzman said. “We think we can potentially end malaria and make HIV and TB fully manageable diseases for people.”

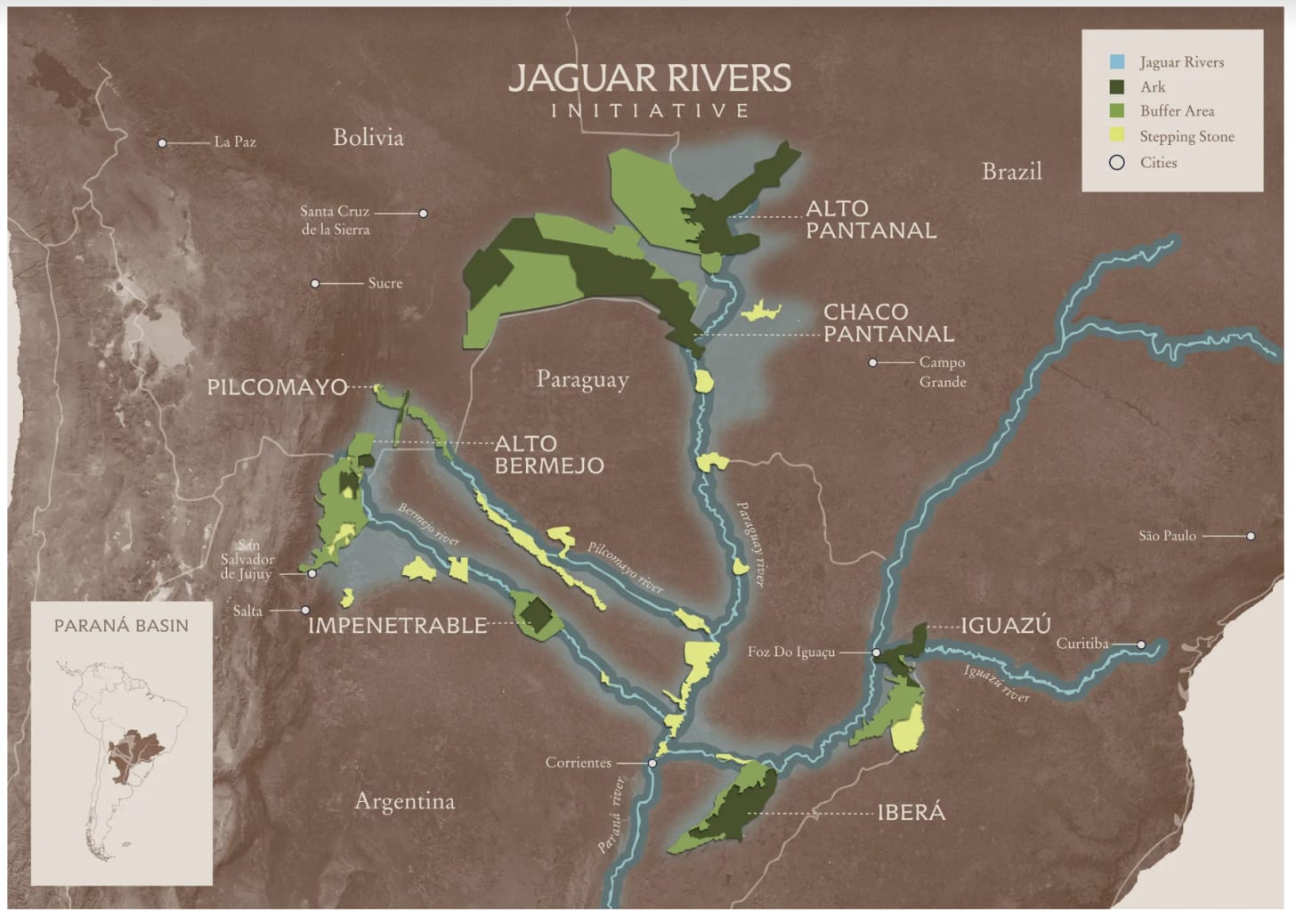

At Climate Week, another announcement took our breath away — the launch of the Jaguar Rivers Initiative, a cross-country collaboration between Rewilding Argentina, Onçafari, Fundación Moisés Bertoni and Nativa, to create a massive wildlife corridor across the heart of South America. Supported by Tompkins Conservation and announced by its president Kris Tompkins, the effort aims to reconnect fragmented ecosystems and restore the jaguar’s historic range. “We all know the urgency of the biodiversity and climate crises,” Tompkins said. “This bold initiative underlines the need for coordinated, large-scale action before it’s too late. I’d call it a lifeline to our planet.”

The week wouldn’t have been complete, of course, without talking about truth and power. As Maria Ressa, the journalist who won the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize, put it “Information integrity is the mother of all battles.” Hillary Clinton warned that, for the first time in 20 years, more of the world is living under autocracy than democracy. The diagnosis was stark. The path forward, less clear.

Then, just as one particularly heavy day was winding down, Audrey Tang, Taiwan’s Minister of Digital Affairs, came onstage and started talking about, of all things, demonstrations in Taiwan against a trade deal with China in 2014. Most mass movements struggle to translate their anger into actionable demands; Tang’s hacker collective .g0v came up with a solution: a digital platform that evolved into something known as vTaiwan.

We hear so much about algorithms dividing us, but this proto-vTaiwan did the opposite: when .g0v opened up a space for protestors to post, an algorithm identified consensus statements on which diverse clusters of protestors agreed. These statements were used to draft demands, and .g0v, now with the government’s help, went on to create vTaiwan, which has since been used to write bills and crowdsource laws, from legalising online sales of alcohol to regulating Uber. It was a glimpse of possibility - AI as an enabler rather than a destroyer of democracy.

And then, in one of the final panels of CGI, the President of Kosovo, Vjosa Osmani-Sadriu, told the story of how, 26 years after the war, her country is the third safest in the world, with one of the highest IT competitiveness rates and a thriving economy. “When the world is facing so many horrible wars and conflicts and so many people are suffering,” she said, “Kosovo is such a great embodiment of what freedom-loving nations can achieve when they don’t turn a blind eye.”

There was a time, not so long ago, when Kosovo was considered a lost cause. And yet there, in the ballroom of the Hilton, we were hearing how that story has been completely re-written. It was a potent reminder that everything changes, and often without us knowing that it’s even happening. You’ll read about the death tolls from a war or disease, but the small cumulative steps of healing and recovery never make headlines — until they reach a tipping point.

Being on the ground for those five days stretches your worldview in a way no op-ed or Zoom call can. It’s the chance meetings in hallways, watching someone’s face change as they tell you about their work, catching an idea that completely reframes how you see things.

Nobody left New York this year on a high. Things were heavier, more uncertain. But we did walk away with something more durable - a deep-seated reassurance that the people fighting for a better world aren’t giving up. They’re just learning to fight smarter. Drought-resistant chickens creating economic empowerment for female farmers in Africa. An LGBTQI+ suicide hotline in Illinois operating despite federal funding cuts. A scientist in Uganda named Krystal Birungi genetically engineering mosquitoes so they no longer carry malaria.

Stepping back into the neon glare of Manhattan on the final night felt surreal. Tourists and theatre-goers crowded around Times Square, completely unaware that all week, behind closed doors, a new world had been taking shape. The old model of rich countries writing cheques and calling the shots is dead. The new one is messier, slower, harder to celebrate. But it’s being built by the people who actually have to live with it.

And that might be what finally makes it work.

.png)