You think you’re done, don’t you?

Not done done—not six-feet-under, wrapped-in-a-shroud done. But done enough. You’ve finally got it mostly figured out. Your tastes are dialed in, your values are stable, your Spotify algorithm is basically clairvoyant. You’ve reached the summit of You.

And yet... if past-you could see current-you, they’d probably cringe.

That’s the paradox psychologists Quoidbach, Gilbert, and Wilson formalized in 2013 when they coined the term The End-of-History Illusion—the cognitive quirk that convinces you you’ve reached your final form, right now, at this very moment in your life.

Despite mountains of evidence that you’ve changed dramatically over the years, you still underestimate how much you’ll continue to change. Your beliefs, your preferences, your habits—they all feel like fixtures. Until they don’t.

It’s the human tendency to look backward and see growth, then look forward and see a mirror.

And once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

So what’s going on here?

Let’s chop it up with a few big cleavers: evolutionary biology, psychology, and economics. Because when you start poking at illusions this big, you need tools sharp enough to cut through the layers.

Evolution doesn’t care if you self-actualize. It doesn’t care if you find your purpose or change careers at 40 or discover you suddenly like anchovies. It cares about survival and reproduction. In that order.

So it built you to optimize for the near term. It gave you a brain that trades in short-term risks and immediate payoffs, because that’s what worked on the savanna. Long-term strategic forecasting? That was a luxury for the few hominids who didn’t die of infection or saber-tooth trauma.

From an evolutionary perspective, your future self is someone else’s problem. Predicting that you might want different things a decade from now is cognitively expensive and reproductively irrelevant. So we don’t do it.

The result? A kind of evolutionary presentism—we assume the way we feel today is more or less how we’ll always feel. And we plan accordingly. (Spoiler: this rarely ends well.)

Let’s go deeper. The mind is a master illusionist. And one of its favorite tricks is consistency bias—the tendency to warp your memory so that your past beliefs, choices, and values appear to align perfectly with your current ones. It’s a bit like an internal PR campaign: “See? You’ve always been this wise, this refined, this consistent!”

Then there’s projection bias: the belief that your current preferences are durable—etched in stone rather than scribbled in sand. You assume your future self will want the same job, the same partner, the same routines, the same political opinions, the same flavor of yogurt.

And if that weren’t enough, we reinforce these illusions with identity. We craft a story about who we are, then defend that narrative like it’s a castle. Any hint that future-you might radically disagree with present-you? That’s a threat to the plot.

So we double down. We declare our current self the final edit. The published version. No more rewrites.

But your psyche? It’s still drafting.

Zoom out. If the End-of-History Illusion is warping our sense of self, it’s also warping our systems.

Because if people don’t believe they’ll change, they won’t plan for change. And if they don’t plan for change, they make decisions that are woefully misaligned with their future needs.

They don’t save enough for retirement.

They underestimate future healthcare needs.

They assume their current job will still be relevant in 20 years.

They don’t invest in learning new skills—because they already know who they are.

And this isn’t just a personal issue—it ripples outward. When millions of people behave like this, entire economies drift. Public policy calcifies. Innovation lags. Cultures get brittle.

It’s the economic equivalent of trying to steer a ship by looking only at where it is—not where it’s going.

So what do we do with this illusion?

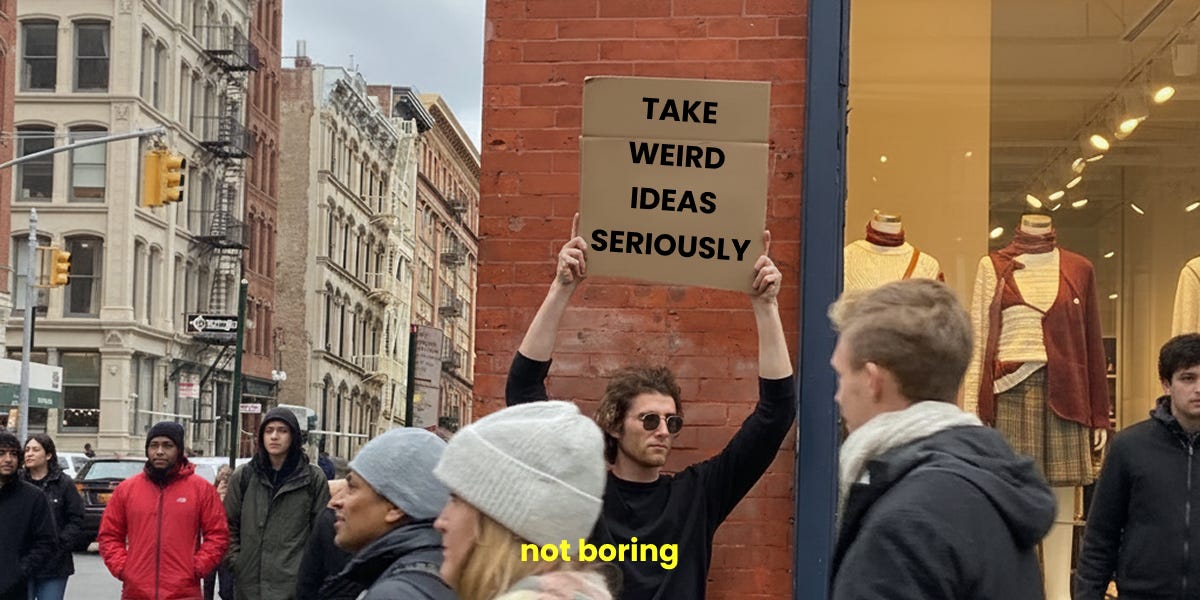

First, name it. Understand that your sense of stasis is an illusion your brain built for comfort—not accuracy.

Then, build a little distance from your current identity. Paul Graham, in his essay Keep Your Identity Small, argues that the more tightly you wrap your ego around specific beliefs or labels, the harder it becomes to think clearly—or change. If your future self will likely disagree with you, how tightly do you really want to cling to now-you’s preferences?

And finally, design your life for change. Build flexibility into your habits, your relationships, your career plans. Leave space for the person you haven’t met yet: future-you.

Because if we take the End-of-History Illusion seriously, then the most rational, most strategic, most psychologically mature stance is this:

“I am still becoming.”

You’re not finished. You’re in motion. The story hasn’t ended, because the character is still changing.

And that, if you’re doing it right, never stops.

What beliefs do you hold today that you didn’t five years ago?

What parts of your identity feel permanent—but probably aren’t?

How are you planning for a future self who might want completely different things?

The End-of-History Illusion isn’t just a bug—it’s an opportunity. A reminder to stay curious, stay humble, and leave room for your own evolution.

After all, the most dangerous version of yourself is the one who stops updating.

.png)