defined | authorial intent | the American epic | criticisms | the zeitgeist | all the authors | influence | structure | themes

What is The Great American Novel?

"The "Great American Novel" is the concept of a novel that is distinguished in both craft and theme as being the most accurate representative of the zeitgeist in the United States at the time of its writing. ... the American response to the national epic." (Wikipedia, Great American Novel, retrieved March 21 2009)

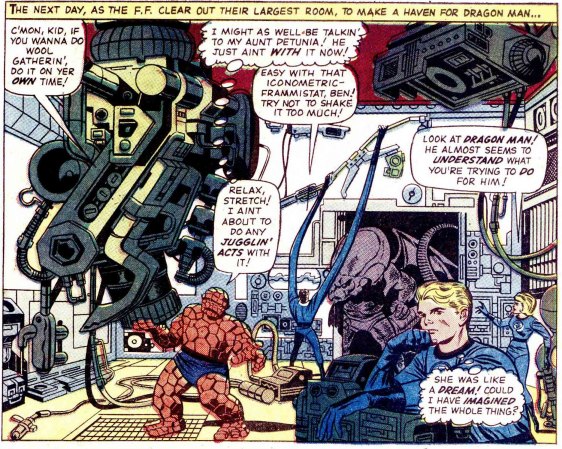

John William De Forest invented the term in 1868 and said that such an epic could not be written until America had "agonized and conquered through centuries." This period arrived in the 1960s. De Forest dreamed of something uniquely and indisputably American, reflecting America's self image. Nothing fits that description more than the superhero. Pulitzer prize winning author Michael Chabon suggested that "the summed output of comic books is itself the elusive Great American Novel, a collective project, of and for the people, as vast and as egalitarian as the American ideal itself. It's just a simple matter of choosing the right books." (the conclusion to Jon Adam's "the Essay", broadcast on Fri, 20 Jan 2012, 22:45 on BBC Radio 3.) It's "a simple matter of choosing the right books." Which books are best? Well what if "the king of comics" (Jack Kirby) teamed up with the greatest comic writer/editor in history? What if they then produced the greatest ever comic (see below)? What if, for the first time, a superhero comic was grounded in realism? What if that spawned the most successful comics company and revitalized the industry? Maybe that would count?

Praise for the Fantastic Four

"Lee and Kirby's Fantastic Four run is the Mount Olympus of comic

book storytelling. Nothing else can touch it in its innovation,

sustained excitement, consequential events, and unprecedented character

development." (Mark Engblom in Comic Coverage: March 21, 2009)

"Stan and Jack's Fantastic Four was, at its peak, almost unarguably

the richest and most imaginative comic in the history of the medium." (Mark Waid's Fantastic Four Manifesto, in "Comics Creators on Fantastic Four" page 202.)

"Those fifty issues [FF25-75] were, simply put, the best super-hero

comics ever done and nobody, let me repeat that, nobody, has done it

better." Marv Wolfman

"For about twenty Issues, on either side of 50, it was possibly the best comic book ever done." Len Wein

"The general wisdom is that the Stan and Jack Fantastic Four is the greatest run of any comic book, ever." (Bob Reyer, comics expert on talkingcomicbooks podcast 89)

Ninety percent of comics are rubbish. Ninety

percent of every art

form is rubbish. But comics have more potential than most

art forms. Because the most efficient medium of communication is always a comic:

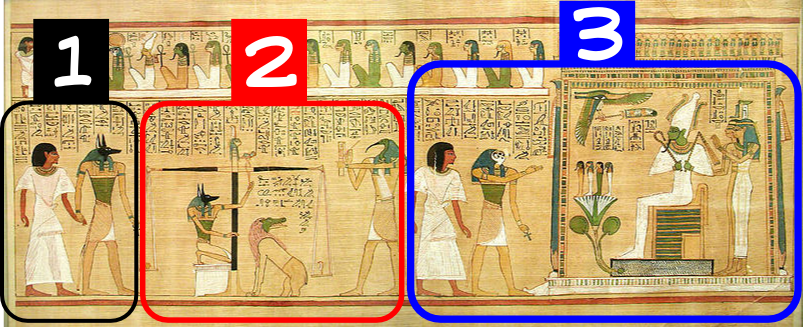

In religion:

If you're a living god, in the longest surviving superpower the

world has ever known, how do you teach your people about the

afterlife? With comics of course. This is from The Egyptian Book

of The Dead, telling how you are led by Anubis to the judgment

hall (frame 1), how your heart is judged (frame 2), and how you

then meet Osiris (frame 3). Medieval churches and Mayan codices

used the same methods.

In fine art:

If you're a great artist, and you want to tell a bigger story

than you can fit into one picture, what do you do? This is

Hogarth's story of the Harlot's Progress (click for larger

images):

In news:

If you publish a newspaper, and you want to get across a complex

idea as powerfully as possible, what do you do? You use a comic of

course. In Britain the master of the craft is currently Matt of the Daily

Telegraph: his panels are frequently quoted on BBC Radio 4's

Today program (the one the politicians listen to), as they sum up

the day's news in the most efficient way possible.

In entertainment:

If you plan to make a movie, or a 3D animation, you need a way

to tell the same story to your production team, but in less time

and with less money. What do you do? What medium can do the same

job as a movie but faster and cheaper? A comic of course (they

call them storyboards)

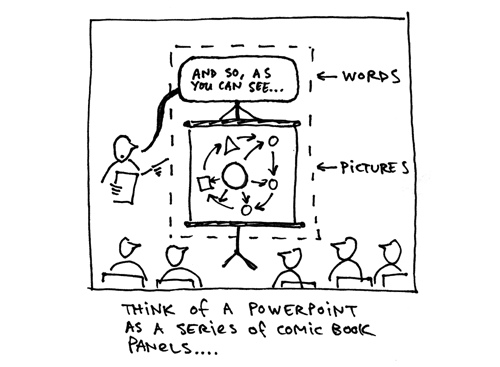

In business:

If you're in a meeting and need to get a message across as

efficiently as possible, what do you use? A comic of course. As Austin Kleon points out,

PowerPoint presentations (and their accompanying storyboards) are

sequential narratives using words and pictures: comics by another

name.

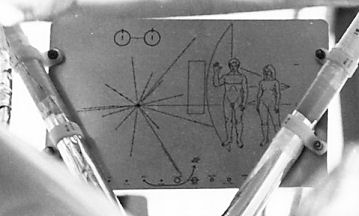

In science:

If you're sending the Voyager spacecraft into deep space, and you

want a message for any aliens out there, what do you do? You use a

comic of course. Now obviously we don't know what language an alien

would use, or if they read from left to right (or from the middle),

but we use words and symbols that tell a story: the characters say

hello, the ship is from Earth, taking this route... it's a comic! Of

course, spacecraft also take up videos and disks and stuff, but

first you have to tell the aliens how to work the thing. So you

create a story in images and symbols: comics always come first.(Image from DamnInteresting.com)

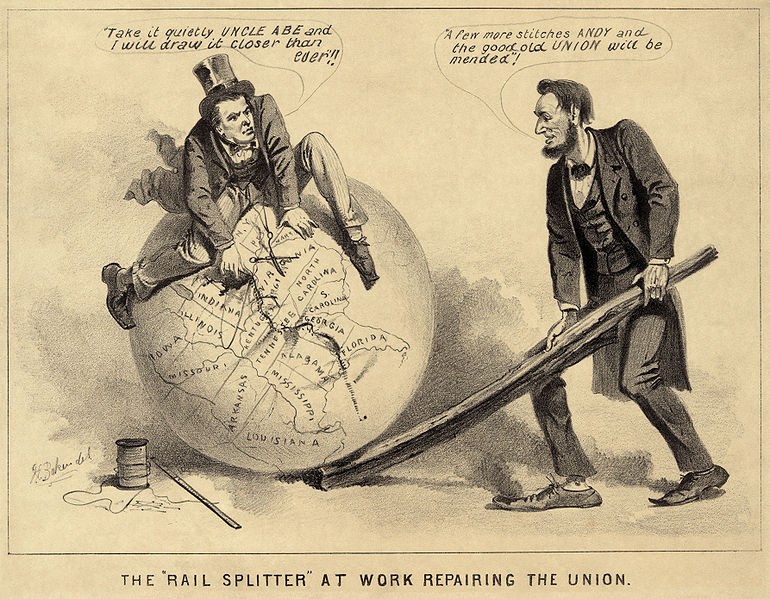

In politics:

If you're a major historical figure, and you want to tell the

world about your triumphs, what do you do? You could write a book

and just hope people read it... or you make a comic. Take the

Bayeux Tapestry, or Trajan's column, or the thousands of other

tapestries and bas reliefs around the world.

The bottom line is that pictures are good, and writing is good, but pictures and writing are better.

"Accidentally" creating a seamless epic

Jack Kirby did not plan a thirty year story. They just wrote what seemed interesting at the time. The only rules were to make it exciting yet realistic. This approach created the most natural, organic story of all:- Realism naturally creates a

long term story

We have instincts. We naturally grow up, find partners, have children, and then they grow up. None of this is consciously planned yet it happens.

A good writer understands the patterns of birth and death, of school and work, or war and peace. Stan and Jack did not plan ahead, but they knew when it was time for Reed and Sue to date, to marry, to have children. The long term story naturally arose. - The zeitgeist naturally

creates a long term story

If fiction follows the zeitgeist then it naturally follows real world patterns: the Fantastic Four follows the optimism of the 1960s with the soul searching of the 1970s, then the materialism of the 1980s. it follows the sexism of the 1960s, the feminism of the 1970s and the vanity of the 1980s. Each phase naturally leads to the next because it's based on the real world. - Cliches naturally create a long term story

Cliches work because each cliche carries a wealth of meaning beyond the simple words or event. In other words, it implies a big story, even if that big story is not spelled out. - Reader reaction naturally creates a long term story

Some critics ('reader response' critics) argue that the meaning of art meaning exists entirely in the reader's mind. One objection is that this would make it impossible to learn from art. But if art reflects real life then the reader is simply learning from real life: the meaning is there, but the artist may not be aware of it.

Authorial intent: "But Jack didn't intend that..."

The Fantastic Four contains ideas that the writers did not intend. That is very

common for great novels. I

recommend listening to the Oxford University podcast on why

we study Shakespeare. We study because we can get so much

out of it! We certainly see things that Shakespeare never

intended, and that's what makes him so great: he produced

something bigger than himself. For more parallels with Shakespeare, click here. The topic of authorial intent is a big one,

but here is a summary from Wikipedia:"New Criticism, as espoused by Cleanth Brooks, W. K. Wimsatt, T. S. Eliot, and others, argued that authorial intent is irrelevant to understanding a work of literature. W.K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley wrote in their essay The Intentional Fallacy: 'the design or intention of the author is neither available nor desirable as a standard for judging the success of a work of literary art.' The author, they argue, cannot be reconstructed from a writing - the text is the only source of meaning, and any details of the author's desires or life are purely extraneous. Such thinking essentially states that the author's intended meaning and purpose for the exposition are fundamentally unnecessary to the reader’s interpretation."

This is illustrated by common anecdotes about famous authors who do not see their work the way their readers see it. For example, "Writer Ian McEwan describes the odd experience of helping his son with an A-level essay about one of his novels, Enduring Love, and finding his son's teacher disagreed with his interpretation of the novel." (source) Here are more examples from a recent Reddit thread:

"Well, a few years back, on our Matura

exam (a very important exam you need to finish high school in Poland,

and later go to a university) [a] few authors who's texts were on the

test were invited to try it out. They were supposed to write 'what the

author meant/felt when he wrote this part'.

"Back in High School, the

teacher was silly enough to get the author of a book we were studying in

to talk to the class. The teacher got several rude surprises about how

certain themes didn't mean what the teacher thought they obviously

meant. Best to wait until the author is dead before deeming fanciful

meanings and then nobody can disprove them or laugh with real insight."

(user myztry)

When asked what "American Pie"

meant, McLean jokingly replied, "It means I don't ever have to work

again if I don't want to." Later, he stated, "You will find many

interpretations of my lyrics but none of them by me ... Sorry to leave

you all on your own like this but long ago I realized that songwriters

should make their statements and move on, maintaining a dignified

silence." (user SnakeX50)

They barely got any points.

Apparently, the people making the exam (based on what teachers taught

the kids) had completely different ideas about the meaning of those

poems/books than the authors themselves." (user Abedeus)

This "Great American Novel" web site is all about teasing out the influences that informed the ideas, even though each writer was not consciously aware of them at the time.

The American epic

As a civilization reaches its zenith it creates its epic. These are usually stories that define a culture and can be understood by children, but also have depths for adults. Hence the Iliad, the Aeneid, Beowulf, the 1001 Arabian Nights or European Fairy Tales. These are usually collective works spanning many years, featuring god-like heroes.

The epic often draws on sources popular

at the time, and retells them in a way that fits a certain

point in history. As Philip

Pullman has observed, Grimm's fairy tales are about princes

and castles and children's suffering after the Thirty Years war

and Napoleonic wars, which led to the unifying of Germany. The

1001 Nights reflect the new cities of the Islamic civilization in

Arabia and the problems that arise for a previously nomadic

culture. Likewise, the superhero reflects America becoming a

global superpower and moving into space. The Fantastic Four

specifically reflects the triumph over the soviets, 1961-1989.

This is explicit in the first issue: private enterprise, science

and family beat the communists.

The FF represented the zeitgeist of the day. As Darcy Sullivan observes, the Fantastic Four is "an allegory, a secret history of the 1960s":

"Take

Galactus

and the Silver Surfer. On the one hand they represent the father

and the rebellious son, but to us they symbolized all the

terrible dread hovering over us in the 1960s, and the strange

mixture of idealism and power needed to stand up to the

Establishment. For kids with only an inkling of the Vietnam War

and the resistance to it, Galactus' tale seemed pregnant with

hidden meaning. What was that mind-blowing trip the Human Torch

undertook to save Earth but a consciousness-altering psychedelic

experience?"

The allegory goes far beyond the individual characters and stories:

"Fantastic Four's general sense of discovery fit right into the zeitgeist of the '60s. Many comics before and since have emphasized conflict, but few if any have conveyed the same spirit of exploration. What blew us away back then wasn't the size of the fights but the constant uncovering of vast realms: Hidden Lands, Negative Zones, micro-worlds and the like. No perspective was absolute - another dimension was always whirling above us, beneath us, within us. Fantastic Four embraced the era's inclinations toward introspection, cultural anthropology, and internationalism." -Sullivan

Criticisms of the Great American Novel Hypothesis

- Most comics are rubbish? The Fantastic Four, 1-321, is not "most comics."

- Comics are rejected by critics? So was Gone With The Wind (rejected by 38 publishers), M*A*S*H* (17 times), Dubliners (22 times), etc. (source)

- It uses simple language?

So does the Bible, in most translations. So did Ernest

Hemingway, and he was criticized for it as well:

William Faulkner: "[Hemingway] has never been known to use a word that might send a reader to the dictionary."

Hemingway: "Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words?" - Comics are low culture? Everything said against comics can be said against Shakespeare

- These themes are not obvious? This is a sign of depth and subtlety.

- Comics appear very lightweight on the surface? So did Mark Twain.

- Comics are made to a deadline, paid by the page? Charles Dickens used the same method, sometimes adapting his story mid way in response to readers.

- Comics are morality tales that stretch credibility? So were the ancient Greek myths.

- Comics have costumed heroes who hit people? You have just described the Iliad, the archetype of the national epic. Though the Fantastic Four do not wear comic-type costumes.

- Comics have multiple authors? So have the Greek myths. Shakespeare collaborated on some plays. Leonardo Da Vinci had a team of artists to fill in the details. This is normal for any massive epic.

- The Fantastic Four (according to this page) emerged without its authors knowing its big picture? The same applies to the individual books of the Bible. And to every real human life.

- 6000 pages is excessive? It's the same length as Proust's greatest novel (assuming that 1 page of dense text = 2 pages of comic).

- Why superpowers? The powers, like the family relationships, are simply McGuffins to allow different stories: Whatever story you want, whatever the topic, whatever characters, whatever location or time period or relationships, the FF can tell the story.

The Great American Novel is "the most accurate representative of the zeitgeist in the United States at the time of its writing."

The zeitgeist is the spirit of the age:

- It is what it felt like to be there: It is not a summary of what later turned out to be important. A later retrospective can be more insightful, pointing out details that later became obvious. No, the zeitgeist is how it actually felt at the time. The Fantastic Four is the zeitgeist in print: unlike a retrospective novel, each issue is written and published at the time, drawing on whatever ideas were current.

- It is the mainstream, the awareness of the average American,

not the cutting edge. For example, when discussing racism,

Martin Luther King changed America, because he was different

from the mainstream. The mainstream view was still racist, and

he dreamed a dream of a different time when that would change. A

book about civil rights would focus on Martin Luther King, but a

book about the zeitgeist would be far behind him, just slowly

awakening to the idea that apartheid was wrong.

Jack Kirby worked with both the radio and TV constantly on, with the TV sound turned down. His mind was like a sponge for current ideas (see volume 1 of the Comics Journal collected interviews). He frequently produced ideas that later found their way into more famous media. For example, when I read the first Challengers of the Unknown I thought it was ripping off the movie "Jason and the Argonauts" - but he movie was four years later. And when I began to notice his repeated references to spraying vapour that improves our DNA (Challengers 8, Terrigan mists, etc) I had to check that these came before Philip K Dick's "Ubik". Kirby also referred to the time when he wrote a story about the atom bomb before it became widely known, and was visited by government representatives asking where he heard of it. He had picked up the details from science magazines and it just seemd obvious to him that such a thing would one day be made. Kirby was perhaps the greatest ever pipeline for the zeitgeist to the printed page.

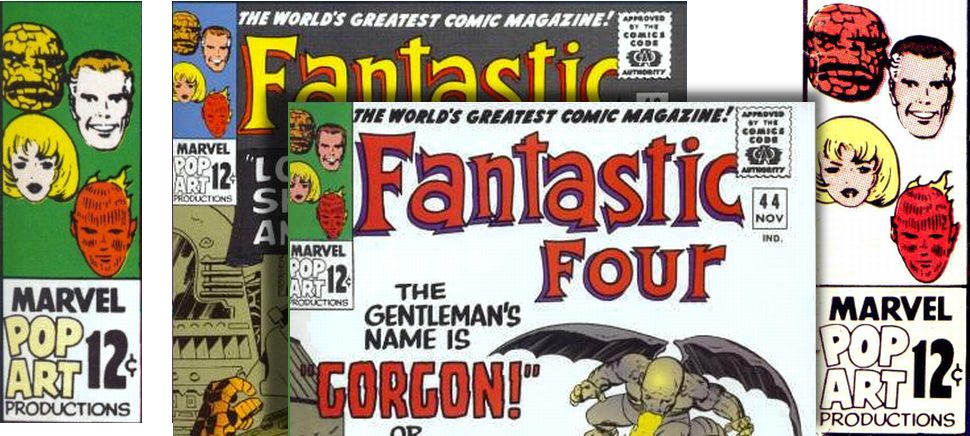

Pop art: "The state, culture, and perspective of the common American citizen."

Perhaps the purest example of the zeitgeist in art is "pop art." Pop art brings together the ordinary and familiar to represent the spirit of the age. The Fantastic Four is pop art, and was re-branded as such at the start of its golden age (issues 42-46).

Examples of the zeitgeist

In General, the FF is about American optimism, America's family values in tension with individualism, and the nation's rise to being the sole superpower. The characters have superpowers because America is a superpower. The story begins when the space race hots up (1961, the first man in space) and ends when the cold war ends (1988-89). Each decade is reflected in the stories. It goes without saying that the clothing, hairstyles, cars and attitudes all reflect the contemporary fashions. For the zeitgeist of each year and each month, see commentary on individual issues.

The 1960s:

This decade is about the cold war and space race, and endless

American optimism. The FF is led by a scientist with 1950s

patriarchal values, who uses giant machines: a symbol of early

America's 1960s faith in science and technology to solve all the

world's problems.

But at first there is a strong undercurrent of alienation as conservative ideas from the 1950s are questions and found wanting. Civil rights is also there: the underlying theme of the FF is equality; the FF featured stories on hate at the time of JFK's assassination; they had the first black superhero, and his title (the Black Panther) predates the revolutionary organization.

Mass

culture:

Individual issues are almost a checklist of popular mass culture

of the time. Cultural homages include:

- 1950s Monster movies: FF1

- The Jewish Golem: The Thing

- The Cold War: FF1

- 1950s Sci-Fi comics: FF2

- Invasion of the Body Snatchers (fear of communist infiltrators): FF2

- Golden age superheroes: FF4 (Sub-Mariner)

- Pirates! FF5

- Pygmalion: The Puppet Master (FF8-300: his puppets come to life; his treated his daughter like a puppet, and she ended up changing him)

- The Day the Earth Stood Still (Planet X, issue 10)

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea: FF 14 (a giant squid attacks the Puppet Master's sub)

- Egyptology and Forteana: FF19

- "Hitler lives!" 1950s sci-fi: FF21

- Dracula: FF30 (first mention in a modern Marvel comic)

- Jacobean tragedy: FF32, 37

- The world of molecules and atoms (the Microverse)

- Other dimensions and antimatter: the Negative Zone

- The Rubaiyat: Passim: one of Stan's favorite books to quote in dialog

- Prisoner of Zenda: Latveria (particularly in Annual #2)

- Shangri-la: the Inhumans' home

- Paradise Lost: FF48-50 (the surfer rebels against "God" and is cast down to Earth)

- The king in the mountain folktale: FF 54

- Prester John: FF 54

- Alien astronauts/Xenogenesis theories: FF 64-65 (Kirby went much farther with this in his Inhumans origin and Eternals stories)

- The Golem, Kabbalah, and the Pygmalion myth: FF66-8 (man making life from clay)

- The Day the Earth Stood Still: FF 73-77

- Chariots of the Gods - a year before Chariots of the Gods was published! (the Sentry Sinister)

- The Prisoner (TV series): the FF in Latveria (confirmed by Bullpen Bulletins)

- The Creature from the Black Lagoon: as "The Monster From The Lost Lagoon"

- Gangster movies and Spartacus: Ben Grimm on the Skrull worlds

- The moon landing: FF 98

...and many more.

The 1970s:

This decade is about self doubt and disharmony. The optimism ends:

overstretched, Reed is sick for most of the decade (reflecting

Vietnam, Watergate, and national self doubt. etc.) Reed collapses

through over work, Reed and Sue separate, both are worried and

miserable for the early 1970s, they are reconciled, but the old

naivety is lost. Reed loses his powers and the team disbands. The

theme of feminism is particularly clear, with the once most

powerful male on Earth reduced in the public mind to to a second

rater, a teddy bear, after being humbled in a public ally staged

fight with a warrior from an all-female planet. A warrior who then

recognizes him as the only male she can admire and respect: a new

status quo is achieved.

The 1980s: money and property,

women in charge, etc.

Examples of real world themes from the 1980s are the rise of right

wing family values as a political wedge issue, the rise of Wall

Street, and women in positions of real power. These are of course

reflected in the FF. Property ownership is everywhere:

- The Baxter Building becomes a star in its own right (e.g. in "The House That Reed Built"),

- Reed buys the Baxter Building, instead of renting.

- The Baxter Building is destroyed so the FF can build an ostentatious 1980s style headquarters

- The Inhumans moved their entire city to the moon.

- Doom physically rebuilds his castle and nation.

- Johnny moves into a trendy old apartment

- Reed and Sue move to a suburban house

- Doom creates an idealized small town for the team.

1980s style Conservatism is reflected in John Byrne's run, an

attempt to get "Back To The Basics." Sue becoming thinner (with a

bigger bust of course), and more violent, and loses a baby. The

change to a dominant, cropped haired Alicia is also notable.

The Great American Novel must be written by "An American author who is knowledgeable about the state, culture, and perspective of the common American citizen" (Wikipedia).

Everyone who creates the FF openly states that they are following

the vision of just two men, Stan Lee

and Jack Kirby.

Lee was a likeable huckster who dreamed of

Hollywood. Kirby was a tough street kid from a poor

neighborhood, an avid consumer of pop culture. Both men were Jews,

New Yorkers, and WWII veterans. Lee and Kirby were

America personified.

The Fantastic Four had a third author: the readers. The comic listened and gave them what they wanted.

This author is "knowledgeable about the state, culture, and

perspective of the common American citizen" because he and she is the American citizen!

The language of the common people

What was the average American reading? Not Melville, not Hemingway, not even Twain. They were reading comic books, because comic books spoke their language.

Influence on other literature

-

Regarding popular literature in general, the "tortured powerhouse" was invented with The Thing. The idea that a being could be genuinely unstoppable, and loved, yet still hate himself, is a reflection of modern day insecurities.

-

Regarding comic books, the Fantastic Four gave rise to the silver age of comics, when superheroes were taken seriously. Other comics and companies soon followed, but any reference to superheroes that takes the idea seriously has the Fantastic Four to thank.

-

The book had a more direct influence on certain novels and movies. For example, regarding Reed and Sue breaking up in issue 129, "Decades later, novelist Rick Moody would describe this story line in 'The Ice Storm,' his roman a clef about familial disintegration." ("Marvel Comics: The Untold Story" by Sean Howe p. 139). "The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao" by Junot Diaz opens with a reference to the FF: "Of what import are brief, nameless lives, to Galactus?" and refers to the FF in many places. The story of the Silver Surfer features prominently in the 1983 movie "Breathless" with Richard Gere, and the hit movie "The Incredibles" was a thinly veiled pastiche of the FF.

But generally the qualities of the FF have not yet been

recognized. Even fans treat the comics superficially, mocking

issues they do not understand (such bas FF 80, Tomazooma). This

web site exists to persuade people to take a closer look.

Influence on language

Before the 1960s, the word "fantastic" had the primary meaning of "impossible" and sometimes "grotesque." It was occasionally used to mean "wonderful" but that sense was rare, even trivial. However, "In popular usage, the word 'fantastic' has become a casual term of approval, a synonym for 'great' or 'brilliant', and this has to a great extent supplanted the original meaning of the word." We see this in one of the earliest ads for the Fantastic Four, from early 1962: the greatest "Fantasy Magazines" include "The Fantastic Four" with "America's greatest "fantasy characters".

When did the change from "impossible" to "good" occur? The "impossible" meaning was still

dominant until the 1960s in academic texts. But by the late 1960s

"good" was the common meaning, hence in Britain we had a comic

imprint called "Power comics" with the titles "Pow," "Fantastic"

and "Terrific": by the late 1960s the terms were interchangeable and

commonplace among the young. As for the older generation in 1973 structuralist critic Tzvetan

Todorov was the first academic to reflect the new meaning. In his

work "The Fantastic", the "impossible" meaning was shifted to mean

not impossible, but

instead the uncertain area between

the impossible and the possible. That is, something exciting,

something that attracts our interest.

So something happened in the 1960s to change the word meaning in the

minds of the young. What was it? The movie "Fantastic

Voyage" released in August 1966 is one candidate, but this was

only a few months before Britain's Fantastic comic (February 1967) so by

then the "good" meaning was already common. Besides, the movie only

appeared briefly (this was long before video) and was intended for all

ages: the change we are looking for took place earlier, mainly among the

young, and was around for long enough to make a difference. What were

young people reading month after

month? Comic books. What were most influential comic books at the

time? Marvel comics. What was the flagship title, the first and biggest

seller? The Fantastic Four.

In 1961 the name "fantastic" was chosen because it

suggested the impossible. By 1966, the highpoint of the comic (see Galactus, etc.) it had redefined

the word to mean wonderful. For more details, see Todorov's "The Fantastic",

or chapter 1 of Robert Papetti's "Fantastic Four In The Silver Age Sixties: A

Tribute".

Influence on culture

When modern critics think of forward thinking cultural influences

in the 1960s they think of shows like Star Trek. But in the 1960s

the Fantastic Four (and its universe) probably had a greater

influence.In the 1980s the Fantastic Four was first mainstream comic to mention homosexuality, and it did so in a positive way. But long before that It was the first mainstream comic to show that a loving family could be other than mother, father and children. Dr. Ramzi Fawaz (of George Washington and Georgetown Universities) went further in his March 2013 lecture 'Flame On!: Nuclear Families, Unstable Molecules, and the Queer History of The Fantastic Four'. "Fawaz sees this mutated family unit as a symbol of the differently-adapted individual, the nucleus of a chain-reaction of counterculture that would overtake the real-universe America by the end of the same decade. [...] Fawaz detailed the wardrobe of masculinity among the FF's three leading men - pliant, effete intellectual Reed Richards, hard bodied but insecure Ben Grimm, literally flaming, unruly yet envied Johnny Storm, and the assertive femininity of Sue Storm, in control of what males can see through her invisibility and able to literally repel them with her force fields. " (source) Ben Grimm in particular, though not gay, is a classic example of queer culture.

In addition, the Fantastic Four expanded the horizons of

literature by making the most extreme form of fantasy (the comic

book) believable. It was the first mainstream comic to feature a

black hero (who unlike other black characters then got his own

title). "New York Times

editorialist and race-relations historian Brent Staples,

[remarked on] how archetypal loners, literally caught between

worlds, like the Silver Surfer, resonated with his experience as

a Black reader in a racially divided country more than did the

handful of 'minority' characters introduced in those times

ostensibly for readers of color to identify with." (ibid)

The book also snuck underground rebellion and the drug culture

past the then-rigid Comics Code Authority, through stories like

the Inhumans (a secret race of enhanced beings hiding underground

in New York, with their roots in a great refuge hidden in the

Tibetan mountains) and the metaphorical drug trips of FF76-79.

Influence on other comics

Marvel became the biggest selling American comics publisher by far, and

all other publishers (that share the same markets) are heavily

influenced by the Marvel style. And all modern Marvel comics are

tributes to the Fantastic Four. This was stated by Tom Brevoort, in

response to a question on why the Avengers and X-Men have so many

spin-off books but the FF apparently do not:

"Every book in the Marvel line is a franchise expansion of FANTASTIC FOUR. It’s just that, in the 1960s, they tended to do this stuff differently than we do it today. But X-MEN was created specifically in response to publisher Martin Goodman’s desire for 'Another FANTASTIC FOUR.'” (source)

Cultural influence in the 1960s: the Fantastic Four v. Star Trek

Many people have commented on how Star Trek pushed the boundaries

of popular culture, but the Fantastic Four usually did it first,

and to a wider audience. TV shows had much higher initial audiences, but comics

reached more people and in a more intense way.

Who was first?

Who came first matters. Each change establishes a precedent and

encourages others to go further. An early subtle change may then

be more significant than a later more blatant change. So it

matters that the Fantastic Four (1961-) came before Star Trek

(1966-69).

How did they pushing the cultural boundaries? Let us take the

most famous Star Trek example: the interracial kiss, in 1968. In

this, Kirk was mind controlled, and had little choice. What

message does that send? "I will only kiss another race if I have

no choice"? In contrast, between 1962 and 1964 Sue Storm had a

genuine romance with a member of another race: Prince Namor. Since

1965, Johnny Storm has been in love with Asian Crystal and

frequently kissed. Crystal is actually a member of another race

that includes a man with hooves and another man with green scales

and fins! Nothing says interracial more than the Inhumans - if you

want to discuss prejudice, just look at their name, they were

Inhuman, he found them living underground in the run down inner

city area of New York, yet Johnny loved her. Or if you want a

positive black role model, how about their close friend the

scientifically and culturally advanced Black Panther? Or if you

really want to focus on a different skin color and romance, this

was a dominant theme for The Thing since 1961. The message of

tolerance in the Fantastic Four is not as blatant as a token

female and single kiss, but it runs much deeper, it's not an

intentional attempt to be liberal, it's just a natural growth from

the story. Race relations is about more than skin color. "New York Times editorialist and

race-relations historian Brent Staples, [remarked] on how

archetypal loners, literally caught between worlds, like the

Silver Surfer, resonated with his experience as a Black reader

in a racially divided country more than did the handful of

'minority' characters introduced in those times ostensibly for

readers of color to identify with." (source)

Which reached more people?

What were Star Trek viewing figures? "The first season was 15 million, second season was 14

million, third season was 10 million. (Making of Star Trek V, p.

42, Harve Bennett.) He also added that a shot needed to have 20

million to be a success." (source)

Star Trek figures declined and it was canceled. In contrast, a

typical issue of the Fantastic Four in the mid 1960s sold one

third of a million copies, and every year sold more than the year

before (until 1968). At first that seems like a slam dunk for Star

Trek. But early Fantastic Four stories were simplified into TV

cartoons at the time, so that raises their profile. And that's

just the start.

The flagship for an interconnected universe: what started in the

Fantastic Four was then expanded elsewhere. For example, the idea

of heroes being hated was expanded in Spider-Man. The cosmic

elements were expanded in the pages of Thor. The Silver Surfer and

Black Panther got their own comics. It was all part of a single

story. Taking that story as a whole, Marvel

comics

sold around 8 million issues a month. This continued month

after month, year after year, whereas Star Trek was only on TV for

three seasons. In the 1960s there were no domestic video players,

so each Star Trek episode was seen only once, or twice if you were

lucky to catch a rare repeat. But a comic book could be read again

and again, passed around friends, and sold on. It is safe to say

that in the 1960s the Fantastic Four universe reached more people

than the Star Trek universe ever did.

Which reached more young people?

Star Trek's modest viewing figures are often defended on the

grounds of demographics: these were all young people, right?

Actually, no. "According to

Television Magazine, the four episodes broadcast between October

27th and November 17th, 1966 averaged 8,630,000 viewers in the

18-to-49 age group, making up 43% of the show's total audience

[51]. By comparison, during the same period ABC's Bewitched

(which aired opposite Star Trek from 9:30-10PM) averaged

10,210,000 young adult viewers or 37% of the total audience." (source) Note that "young" back then

was anything up to age 49! In contrast, the vast majority of

Marvel readers were under 20, and many were under 10 years old.

The younger a person is, the more a story is likely to influence

them. In demographics, the Fantastic Four wins hands down.

Which was read more intently?

- There were very few TV channels in the 1960s, so some of the

viewing figures will be made up of people who would rather watch

something else. In contrast, there was a huge choice of reading:

if somebody was reading the Fantastic Four it's because they

cared.

- TV is a passive medium. It requires no effort to watch.

Indeed, in the 1960s, before remote controls were common, it

took effort to turn it off. You could be counted as a

viewer even if you were asleep or in another room while the TV

was on.

- Finally, TV was free to watch, once you had the physical set. If people pay no attention it doesn't matter to them. Many (perhaps most) viewers will miss parts of any given story. But if you pay for a comic then you are going to make thee effort to read it all and take it in!

Modern bias

Star Trek fans have done a much better job of getting their material in front of critics. This is due to:

- Popularity: Star Trek

became a huge franchise after the 1960s, whereas superhero

comics have been in long decline.

- Continuity: Star Trek has a clear continuity: so it's simple. But Fantastic Four continuity died in 1991, making the whole mess very confusing.

- Brevity: There are only 79 episodes of Star Trek: the Original Series, plus the pilot. So it's easy to become familiar with them all. But the hundred of Fantastic Four issues (or tens of thousands of connected Marvel issues) can be daunting.

- Accessibility: Most of the 79 Star Trek episodes are easily available on DVD or repeated on free to air TV, with small clips on YouTube. The classic Fantastic Four is much harder for a non-fan to find.

- Simplicity: The Fantastic Four

contains a 28 year story with complex subplots. Star Trek

stories are usually over in a single episode, or two at the

most.

Conclusion

In the 1960s, the Fantastic Four probably had a greater cultural influence than Star Trek. But that is not obvious unless we look at the numbers at the time.

Plot structure

The story follows the classic five act structure: danger, rising action, the ball, crisis and triumph:

Act 1: danger:

The story begins with the crucible that forces the heroes

together: the space flight. The grand quest is then laid out: Reed

wants to save the world, and Sue wants them to be a family. The

four major themes are introduced (reluctant heroes, personal

confidence, the American Dream, and equality), along with the

principle opponents (Doom, Namor, Skrulls) and motifs (would-be

monarchs, hidden races, dangerous frontiers, health, mind control,

doppelgangers and home).

Act 2: rising action:

Here the themes and motifs are expanded and threats

multiply. At the start of this act, threats appeared only at

intervals. By the end of the act, each drama merges with the next.

Act 3: the ball:

All the characters get together (the wedding), and

everything looks bright. This act crystallizes the major themes in

the person of Franklin and hence the need to put family first.

Act 4: crisis:

Everything goes wrong. Reed can no longer cope. There is a

false triumph and false dawn half way through (FF200) then things

get even worse.

Act 5: triumph:

The crises are finally solved through family values: Reed accepts

what Sue was telling him all along and all their problems are

neatly resolved, leaving to the start of the next epic.

Multiple layers

The FF is probably the most layered book ever written. At least twelve layers of story are told simultaneously, and each layer can include multiple characters. Why is it so complex? Because it evolved organically through multiple people. The result is far richer than any individual could consciously achieve. Layers include, from smallest to largest:

- The frame: at its best, each frame tells a story. Imagine each frame on this page, blown up to Roy Lichtenstein scale.

- The page: a well crafted page is rewarding even if you can't read: amazing people are doing amazing things.

- The issue: even multi-issue stories had a unique story of some kind per issue

- The arc: three or five issue stories ere common.

- Minor Subplots that weave in and out of the main story, often over many months.

- Links to the wider Marvel Universe (the other connected comic titles).

- Major subplots: multi-year stories (e.g. exploring ever further, and romances)

- Major "villains" (Namor, the Skrulls, Doom, and the Mole Man) have their own 28 year story

- The main characters develop consciously over the years (e.g. Ben goes from angry to depressed to resolved to happy)

- They also develop unconsciously (e.g. Reed becomes suicidal, but never admits it to himself)

- Themes: these build to their climax over the full multi-year length.

- The big overarching 28 year story (choosing priorities)

- The endless story: the 28 year story, the Franklinverse, the next team, and other major epics (Spider-man, the X-Men, etc.)

Most of these layers are hidden at first glance. People often pretend all is well when they are hurting inside, or they may not see the importance of an event until years later. But look for the depth and it's there.

Subplots that cover the five acts:

Each issue typically introduces a new short subplot, but some subplots extend over all or most of the entire 28 year story. Each has its own beginning, middle and end.

Individuals:

- Doom and The Mole Man have their own page.

- Franklin represents the core theme of Reed treating Sue's input as equally valuable. His story begins with the "will they or won't they marry" subplot, through his birth, early years when they didn't know what to do with him, and their final realization that he is the key to everything and must be their number one priority.

- Alicia's frustration and despair, resignation, giving up and finally seeing new hope, match Ben's career. She is a more extreme version of Sue: apparently weaker, but only she could stop Galactus, defeat the Puppet Master, etc.

- Agatha Harkness is at first estranged from her people, a troubled witch who at first seems to be the ideal nanny. She twice saves the FF, but twice betrays them to deadly enemies. Finally, like Reed and Sue, she decides to put her family first (FF223).

- Galactus begins as a deadly threat, and finally becomes Reed's friend: see FF 262. It is debatable whether this is a good thing.

- The Horton family (Horton, the Torch, Toro and their baby Frankie) could be seen as the previous generation's Fantastic Four. They link the team to the previous generation, just as the current torch will lead the next. (see FF annual 4, and various issues in the 100s, culminating in FF244).

Races, empires, and others:

- The Inhumans, thanks to Sue and Johnny, change from deadly enemies to vital allies, and intermarry with the human race, and finally settle on the moon.

- The Skrull empire begins as deadly enemies but finally moves toward galactic peace (in FF annuals 18 and 19).

- Atlantis declares war three times (FF4, Annual 1, and FF 102) and finally comes to peace with the surface world thanks to Sue (see FF149 and 219).

- The Baxter Building starts as a normal tower block, becomes increasingly high tech, is eventually effectively sentient, and is destroyed near the end of the story, symbolizing the end of the first FF team. (The next Baxter Building should be as John Byrne suggested in Comics Creators: the same name but taller!)

- The mystery of the team's powers is gradually unraveled, especially through the Molecule Man (see FF1, FF20, FF187 and FF319).

The most obvious themes are right there on the cover to issue 1:

- Family

- Dangers that are bigger than themselves: danger is a concept repeated on almost every page of issue 1, and constantly throughout the series. Issue 1 is particularly about monsters: there's a monster on the cover, page 1 refers to fears of an alien invasion, on on page 5 they think Ben is Martian, Ben becomes a monster (as he sees it) and they end up fighting monsters on "monster Isle".

These themes are so obvious that they won't be discussed in depth

on this site. Instead we shall focus on the secondary themes:

concerning teamwork.

Themes about teamwork

If The Fantastic Four is summed up in a word, that word is implied by the name, Fantastic Four: it's about teamwork. Specifically, being a hero even when reluctant, personal confidence, equality, and achieving the American Dream.In many ways this is the story of Susan Storm, and a metaphor for every mother who feels the heavy burden of duty while seeming to be invisible. Susan never had a proper childhood (her mother was dead and her father in jail), and had to raise her younger brother while barely more than a child herself. All she ever wanted was a normal family life, but fate had other plans. Instead, she had to save the world, as a superhero with almost no power (at first) and no respect. The Fantastic Four is the story of how she persuades her husband to notice her, and through her to notice his family, and finally put them first.

The first issue introduces the four themes (reluctant heroes, personal confidence, equality and the American Dream) and these are developed through the story and are resolved in act 5. As we would expect in The Great American Novel, these themes also apply to the United States in this period.

1: reluctant heroes

We must be heroes even though we don't

want to be.

Reed, Sue and Ben never wanted to be superheroes. Johnny is the only one who loves the lifestyle, and he is in the shadow of the others. By the end Reed and Sue finally get the life they want, and Ben and Johnny are well on their way.

This reluctance mirrors the United States' Founding fathers who wanted to avoid European wars, but their nation finds itself involved in almost every conflict on the planet.

2: confidence

Success depends on confidence.

Reed's tragic flaw is his belief that only he can solve everything

(a flaw taken to its extreme with his mirror, Dr Doom): this

confidence is gradually undermined through the story (reflected in

his health), until he gains respect for others. Ben's story is one

of regaining his confidence, Johnny loses his, and Sue becomes

more assertive on the surface while losing confidence under the

surface. At the end, all find their true selves.

This all reflects America's initial pride in the 1960s (faith in science, expanding business, moon landing, etc.), loss of confidence in the 1970s (Watergate, oil crisis, Vietnam, etc.), and finally winning the cold war in 1989, when the 28 year Fantastic Four story ends.

3: equality

All men (and women!) are created

equal.

The whole story can be seen as one of sexual equality: Sue's

apparent weakness (she prefers listening and caution to fighting)

is more effective than Reed's hard power (conflict), which

increasingly fails. Those who appear to be enemies are sympathetic

and can become friends (the Mole man, Namor,etc.). Sue's softer

role is crystallized in Franklin: he appears to be a liability, a

baby in need of saving, but is in reality the most powerful one of

all. Both Reed and Doom, the proudest of all, are finally defeated

by their children. Meanwhile, Ben learns to stop ignoring Alicia's

needs and abilities (for example, Alicia is the only one who can

stop Galactus), Johnny learns the hard way not to be sexist, and

Doom learns that his success depends entirely on the respect he

gives to Latverian peasants.

This reflects America both internally (civil rights, women's

liberation) and externally: America's soft power through trade and

entertainment, which treats other nations as equals, is far more

successful than its hard power through forced regime change, which

tries to treat other nations as naughty children.

4: the American Dream

Anyone can make it, and have it

all.

The American

Dream is the national ethos of the United States, in which

freedom includes the opportunity for prosperity and success for

everyone, through hard work and decency. Reed achieves everything

through his genius; Ben was an ordinary kid from a tough

neighborhood who became a war hero and star test pilot through his

hard work; and. Johnny and Sue are orphans who, through Sue's hard

work and their courage (joining the dangerous space flight) became

celebrities. The team is shown as having a penthouse suite, global

fame, a flying car, and everything people dream of. Several early

stories praise office work and celebrity culture.

Historically the Dream originated in the ever expanding frontier,

a central motif of the Fantastic Four. It was particularly marked

among 19th century Jewish refugees: both Stan Lee (Stanley Lieber)

and Jack Kirby (Jacob Kurtzman) were Jewish, as is Ben Grimm in

the story. Most of the team's early foes are old world style

monarchs or attempted monarchs: Doom, Namor, the Mole Man, Kurrgo,

Puppet Master, etc.

The story also reflects criticism of the Dream: the team also reinforces class inequality: Reed had a genius was a millionaire whose father was an equal genius, Sue and Johnny's father was a star surgeon, and Sue benefited from movie star looks: the only completely self made member was Ben, and he gets the ugly treatment and is treated like an idiot by Reed and Johnny. Reed, the highest achiever of all, realizes that no amount of effort will guarantee success (in act 4). But this is simply a reflection of the true American dream: a happy family based on good values. Their happiness and ability to solve problems ultimately does not depend on their wealth but on whether they treat each other with respect (see the major theme of equality).

Motifs

The story features recurring motifs including:

- Monarchs and would-be monarchs: see the themes of the American Dream and equality.

- Hidden races: (Subterraneans, Skrulls, Atlanteans, Inhumans): these illustrate these theme of equality by showing we are not the only race.

- Dangerous frontiers: (outer space, the Negative Zone, underground, the oceans, the Microverse, other dimensions): the foundation for the American Dream of constant improvement.

- Mind control: (especially from Doom and Maximus): this forces us to examine what makes each person unique. It is closely linked to the motif of doppelgangers, the problem of fighting against yourself.

- Doppelgangers: (duplicates of the team): these highlight the themes of confidence and equality by showing the futility of constantly fighting: you will always find an enemy who is just as strong, so the only long term solution is to come to some kind of agreement, or use their narrowness of focus against them.

- Home: (the Baxter Building is described as the fifth member of the team): this emphasizes two themes: the American Dream (having a great home), and equality (the value of the family as a team).

- Reed's long-term health: Reed's long-term health (i.e. beyond one or two issues) reflects his confidence. His stretchable face looks younger and more handsome when he's succeeding, and serious decline is accompanied by collapsing (twice near the start of act 4), loss of stretching powers (157-199), and even aging to near death (FF205-214).

- Biblical language, themes, and structure.

- Recurring characters are also motifs, and they usually combine some of these general motifs. E.g. Doom is a monarch who is almost Reeds doppelganger, and specializes in mind control; Namor is a monarch with a hidden race, etc. Their significance to the story is discussed in the issue by issue summary.

Why study the Fantastic Four?

The Fantastic Four is the Great American Novel. It is therefore the modern Shakespeare.

The Fantastic Four is an allegory of the most powerful nation in the history of the world, during its triumphant phase: from its first man in space (1961) to the end of the cold war (1988-9). A nation is understood through its art, and the superhero comic is America's unique contribution to art. (Western movies are also unique contributions, but no movie spans so many years or topics.)

The Fantastic Four is the only realistic mass market superhero

comic (no flashy costumes or

secret identities), and the most literary (they form a

single coherent story).

.png)